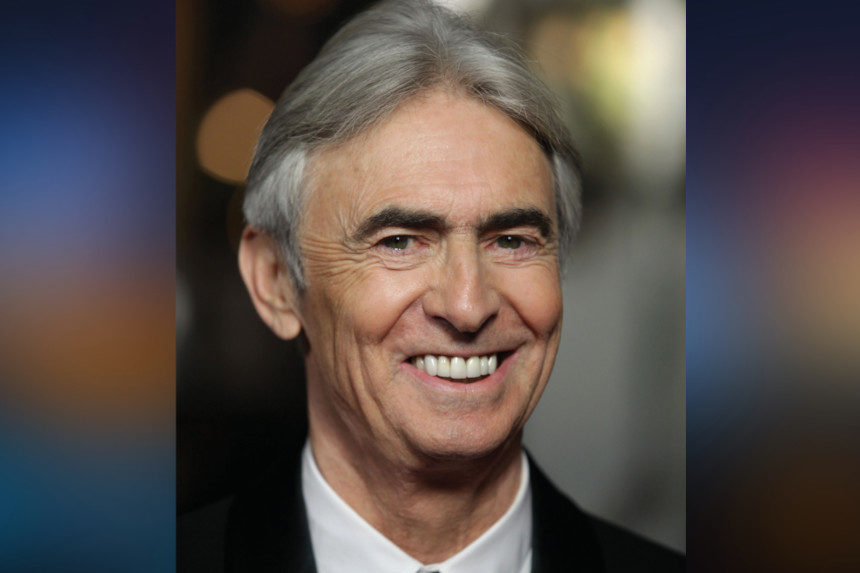

Older readers will remember David Steinberg, one of the best-known comics of the 1960s and ’70s, from his appearances on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (contributing to the show’s cancelation) and his more than ten dozen appearances on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Younger readers will know his work behind the camera, directing many episodes of some of the hottest sitcoms on TV, including Friends, Mad About You, Seinfeld, and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

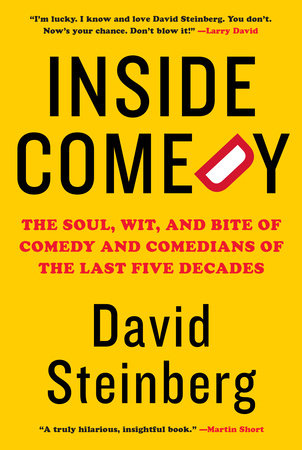

In his new book Inside Comedy (Knopf), Steinberg puts his extensive experience to paper, giving readers young and old a history of life and show business through the perspective of laughter. You could say that he picked the perfect time to take us for a ride through 50 years of making laughs. David was in the middle of a lot of it. As he puts it, “My career has been a dream built on laughter.”

And he knows the best laugh makers well. Every comic and comedic actor who has tickled you has a unique place in this book, from George Burns to Chris Rock and Lucille Ball to Whoopi Goldberg. This is a chronicle of the ups and downs of the funniest people on the planet from a long-time insider.

Jeanne Wolf: Times change, and what people think is funny changes too. Are there any things that will always make ’em laugh?

David Steinberg: Just because something works now doesn’t mean it always will. Every audience becomes a community, and each is different. It is especially challenging in Las Vegas because they are all from different places and not a community. And then there’s the alcohol.

JW: In your book, you pick comic stars who represent particular eras, to show how change happens. Is there a kind of timeline of the big names that guided comedy’s evolution?

DS: Let’s start with the Catskill comics: No shortage of laughs. No shortage of great comics. Rapid-fire jokes. Then came Lenny Bruce. At his height, Lenny spoke truth to an audience who had never heard things that raw before. Truth about the world, truth about politics, injustice, religion. Raw truth. Lenny was followed by Cosby, a storyteller — very different than jokes. Then came the brilliant Richard Pryor, a combination of them both. Then the observational brilliance of Seinfeld. They just kept raising the bar and breaking formats.

Lenny Bruce and Woody Allen influenced me the most. Seeing Lenny live taught me that a comedian didn’t have to pander to an audience. He didn’t try to bring them in. He taught me that doing comedy is being smart. When I saw him, he spoke softly and told stories that meant something to him. He was very cool on stage. And most importantly, I learned from Lenny that you could dress well and look good and still be funny.

JW: We always hear about comic timing. Can you really learn timing? Does laughter from the audience fuel it and silence throw it off?

DS: Yes, you can learn timing. However, you do need innate, natural talent to begin with. Most people can learn to dance, but few become great dancers. The audience tells you everything as a comedian. An audience listening and laughing is a gem. Silence is the kiss of death. It can throw off your rhythm, but over time and with practice you can learn how to get that back.

JW: Were you funny growing up? Did people think of you as a jokester?

DS: My older brother Fishy always had joke books. I don’t tell jokes, but it must have influenced me. I was funny as a kid because I was precocious and used to tell stories. And I would imitate what I heard at the movies (which I skipped school to go to all the time). I wasn’t a class clown, but I always found humor in any situation. I was a challenge to my teachers.

I ran into musician Randy Bachman [of Bachman Turner Overdrive]. He’s a few years younger and also from Winnipeg, and he told me that when he got to high school, the principal told him he was the “most difficult kid we’ve had here since David Steinberg.” I wear that as a badge of comic honor.

Comedy has gotten me through everything. Laughter is healing. You have to be able to find humor. It’s not always possible. Mel Brooks found a way to get even with Hitler with humor in The Producers. Much of comedy comes from pain. Laughter got my wife Robyn and me through the pandemic and lockdown.

JW: Can stand-up be compared to sports? Experience, practice, practice, practice. Watch other teams’ game tapes. Look for champs to model after and seek an effective coach? Chris Rock says, “learn-learn-learn.”

DS: Stand-up is all about rejection. You can only develop an act by failing on stage. The audience will let you know what does and doesn’t work. Groucho [Marx] once told me that if the audience was looking at their watches they would leave the bit in. But if they were shaking their watches to see if they still worked, they took that piece out. Rejection is a great teacher. If you’re not prepared to fail, don’t be a comedian.

JW: Now, as you say, “Everyone wants to be a stand-up.” How do you explain to someone that it takes years to be able to read an audience? How do you convince a newbie that rejection will be their master teacher?

DS: When I was starting out, the goal was to get a good hour. Now it seems people are looking for a good 10 minutes to get a sitcom. Stand-up takes getting up in front of an audience as much as you can. At times that can be a very painful learning experience. But when it’s working and you’re connected with the audience, that energy is magical and makes it all worth it. As Jerry Seinfeld said, you have to learn to crawl first. Then stand, then walk and hopefully run. But you better be okay with crawling for a while. And that’s tough to get used to. There’s nothing worse than being on stage and saying, “These people don’t think I’m funny at all.” But believe in yourself, keep working at it, and you will run. Or at least walk briskly.

JW: Okay, here’s the perennial question: Is comedy harder because you know you’re crashing and burning if you don’t get that big laugh?

DS: At first it is. It feels like failure. It’s a terrible feeling. But again, failure is par for the course, and you have to believe that. So like a boxer, you learn to take a punch. You take the hit and keep your wits about you, or your wit in this case. You take the punch and move on with your material the way you worked it out over and over again, always letting the audience guide you as to what’s working.

JW: Sitcoms are disrespected sometimes as not being important. You say sitcoms are like jazz — a genuine American art form. Can you explain that?

DS: Sitcoms, when done well, are like a great jazz band. The writers write the notes, the sheet music. The cast members are carefully chosen; they are the musicians. They bring the sheet music to life with incredible timing. The director guides the rhythm, and when all those choices that go into a sitcom are right, that’s when you feel, see, and hear the rhythm.

This is an expanded version of the interview featured in the July/August 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now