Thomas Edison introduced a commercially viable light bulb as early as 1879. But it took another 50 years before even half of America’s homes could get electric light. One of the big challenges was generating and distributing electricity across the country. The other was standardization; every light bulb seemed to operate differently, give off different levels of light, and require its own electrical system.

That changed in 1909, when General Electric introduced its Mazda incandescent bulb, named after the Zoroastrian god of enlightenment, Ahura Mazda. The Mazda bulb used a tungsten filament, which was dependably brighter and longer lasting than the carbonized thread in other bulbs. It also introduced a standard, threaded base to the bulb, which is still used today.

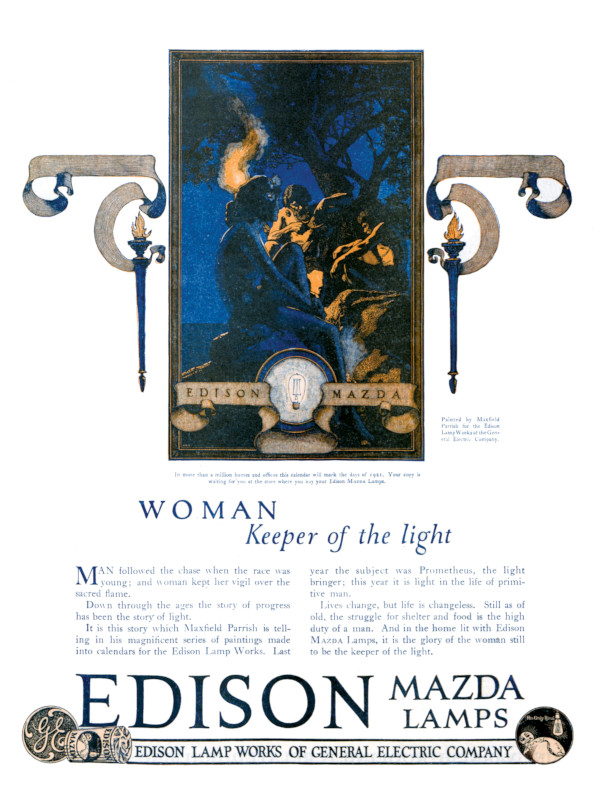

To advertise their bulb, General Electric ran a series of eye-catching ads using art by Maxfield Parrish and, later, Norman Rockwell.

While GE could boast that its Mazda bulbs lasted longer than its competitors, some of those early, carbon-filament bulbs have proved unexpectedly durable — like the hand-blown, carbon-filament bulb that has been burning nonstop in a Livermore, California, fire station since 1901.

This article is featured in the May/June 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is truly a gorgeous example of early ‘modern’ print ads in color. GE obviously was willing to spend the money to have their high quality, long lasting bulbs associated with memorable art by the best in the business. Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell? I rest my case.

The ad copy that went into the selling was thoughtfully placed below the art. The light bulb itself was cleverly drawn into the picture in a manner that blends in beautifully without interfering. They set a high bar for other advertisers to follow. It also has the look of pre or early art deco.