Basil “Tookie” Hendry, a construction contractor in Louisiana, didn’t like the small painting he inherited. He tried hanging it in the stairwell of his home for a while, but eventually decided to get rid of it. He sold it at a local auction house for $1,175 in 2005. Twelve years later, the painting was resold for over $450 million.

How did the picture increase in value so quickly? British art historian Luke Syson decided that it was probably painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and he included it in an exhibition in London’s National Gallery in 2011. Other experts doubted its authenticity, but the approval of the National Gallery increased the painting’s value by $450 million.

What made Syson decide that the painting was actually by Leonardo? Syson explained that when he looked at the painting it “seemed to hover somewhere between our realm and something spiritual.” That “hovering” didn’t persuade former FBI art crime specialist, Robert Wittman. He commented in The Observer newspaper, “why anyone would pay that kind of money for a piece that had questions about it is very strange. That particular painting is not worth what was paid for it. So there is a suspicious aspect to it. And the provenance is very murky.”

The murk only increased after the sale. No one could figure out who spent all that money for the painting. No one would admit to being the new owner. Then the painting disappeared, failing to show up for its scheduled exhibitions. Rumors swirled. Some newspapers reported that the sale was part of an international criminal money laundering ring. Some reported that the painting was secretly stashed away in Geneva, while others claimed it had been spotted on the yacht of a Saudi prince, cruising on the Red Sea. Even today, no one knows for sure.

The mystery of the Leonardo painting is only one of a series of highly peculiar events in today’s overheated art market.

In June, an artist named Salvatore Garau sold an invisible sculpture — literally, a sculpture made of nothing but thin air — for over $18,300. But that’s not the craziest part. Garau has now been threatened with a lawsuit by another sculptor, Tom Miller, who claims that he invented invisible sculpture five years earlier!

Recently a painting by the artist Banksy was auctioned by Sotheby’s in London for $1.4 million. As soon as the sale was completed, the picture dropped inside its frame into a secret shredder, which the artist had hidden there. The painting was quickly cut to ribbons. Footage from the auction showed the panicking Sotheby’s employees removing the picture from the wall and hustling it out of sight. But it turned out that the new buyer didn’t even mind.

A few years earlier one of the most preeminent Manhattan art galleries admitted to selling over 60 fake paintings for $80 million. They claimed the art was by the world’s greatest abstract painters, such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, but in reality it had been painted by a Chinese immigrant, Pei-Shen Qian, who couldn’t make a living selling his paintings on the sidewalks in New York.

Trailer for the documentary Made You Look: A True Story about Fake Art (Uploaded to YouTube by What’s on Netflix)

The fakes fooled all the wealthy collectors, dealers and experts who had examined them, but after the fraud was exposed the painter fled to China to escape criminal charges.

These types of stories aren’t limited to the U.S. art market. This spring, a small painting by a minor artist was listed for sale in Spain with an estimated value of $1,800.

Then someone claimed the painting might be a lost masterpiece by the great Italian painter Caravaggio. How could he tell? “When I saw it, it went ‘boom,’” the London-based art consultant Marco Voena told the New York Times. The estimated value of that “boom” increased the value of the painting from $1,800 to $60 million. The Spanish government intervened and blocked the sale.

Nothing about the appearance of the painting had changed. Physically it was identical. But based on the opinion of a consultant, a work of art thought to be worth $1,800 suddenly increased in value by $60 million. Kind of makes you question whether the “value” of the painting had anything to do with how it looked.

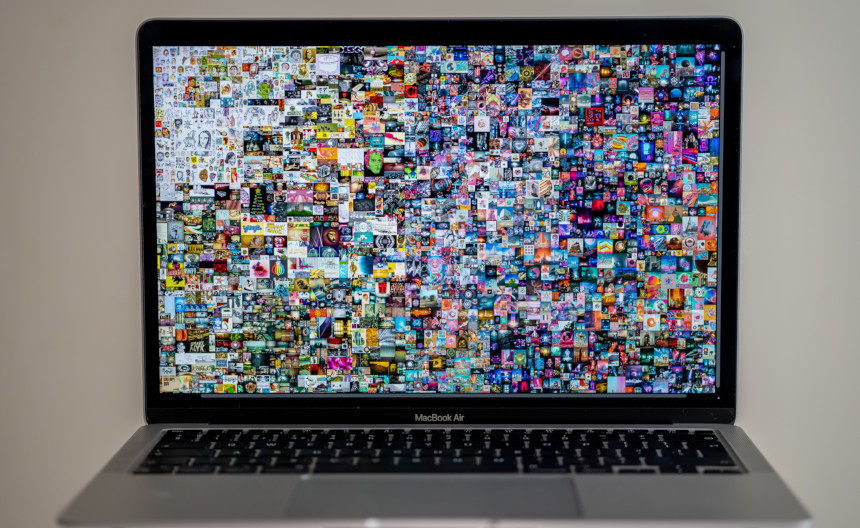

But if all these events seem strange to you, they’re nothing compared to this year’s weirdest art craze: Nonfungible Tokens (NFTs). This year an artist known as Beeple sold an NFT— a digital artwork entitled “Everydays: The First 5000 Days,” for $69.3 million.

An NFT is not a physical picture. It’s just the electronic data for that picture stored on a digital record called a blockchain. An NFT lacks many of the advantages of a traditional drawing or painting. For example, you can’t see it with your naked eye, and if the power grid ever fails, your NFT will disappear. An NFT is not the same sensory experience — it was never touched by the original artist, so it’s not infused with the artist’s fingerprints, sweat and feel. Unlike a traditional painting, the colors of an NFT don’t glow differently in different settings or affect your living environment by its placement. They are not known for being particularly beautiful or well designed.

So what’s so great about NFTs? What do they contribute that a normal picture doesn’t?

One answer may be found in the name: Non-fungible, meaning that it’s unique and can’t be duplicated. Whether the image is good or bad, at least the new owner can rest assured that digital encryption guarantees they own the sole original file, with encrypted proof of ownership. It is easy to make digital copies of an NFT, but the owner of the NFT will always be able to prove on the blockchain that he or she owns the true original.

NFTs are a good example of how today’s art market puts more emphasis on the “market” part and less emphasis on the “art” part. Wealthy collectors pay huge sums of money for art as a status symbol, rather than for the traditional qualities of art, such as beautiful line, color and design. Investment bankers, crypto-currency speculators and other collectors who shape today’s high stakes art market will often hire consultants to identify what is good, or what is worth the investment, rather than purchasing what the collector personally finds beautiful and meaningful.

Economists distinguish between two types of property: property that is valued because of its inherent qualities, and property that is valued simply because other people can’t have it. They call this second type of property “positional goods.”

An NFT is the perfect example of a positional good, because its single most important quality is that it is “non-fungible”— that is, that there is only one of them in the world, and no one else can have it. Originally all art was thought to be non-fungible. After all, there’s only one Mona Lisa or one Sistine Chapel. But in the 20th century something funny happened. Through photography and computers it became possible to make unlimited perfect copies of any image.

This threatened to dampen an art market where highly competitive collectors wanted to have exclusive possession of a cultural object. Today the owner of an NFT can prove that, no matter how many identical digital copies may exist out there, the NFT version is the one, true and original version. Rather than genuine aesthetic appreciation, this possessiveness seems to underlie much of the commercial success of NFTs.

Featured image: A possible Caravaggio (Ansorena.com)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Wow! And here I thought the Post’s latest “You Be the Judge” feature “Fine Art and Sour Relations” was bad enough (and it is), but THIS?! It just got weirder as it went on. Invisible sculpture. Hmm. That’s even more outrageous than ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’. Of course I thought the emptied contents of a vacuum cleaner bag being fawned over by the phony New York art critics over Rockwell’s (remember that?) took the cake. Now I have to say at least it was something physical; disgusting or not. The amounts of money here are really obscene and insane, David. The criminals are calling the shots these days, and we’re the ones getting punished, not them.

I absolutely will watch this Netflix documentary in the near future. No doubt the trailer only scratched the surface of a lot more shock and awe the feature contains. Makes me appreciate art.com more than ever, definitely!