The upcoming Marvel Studios film Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings is based upon a Marvel Comics character that originally appeared in the 1970s, but the roots of the character are over 100 years old. Shang-Chi came together from a variety of pieces, including Sax Rohmer novels, the ’70s Kung Fu craze, and even the James Bond series. Here’s a look back at the various stories that came together to create the Master of Kung Fu, and how further inspirations were woven into the new feature film.

Shang-Chi’s story begins in the 1913 novel The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu by Sax Rohmer. Born Arthur Ward in 1883, the writer took the name Sax Rohmer and was publishing horror and mystery-inspired fiction by the time he was 20. The first novel introduces criminal mastermind Fu Manchu and his enemies, Sir Denis Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie. The idea of an investigating team versus a crime genius definitely echoed Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, and the international adventure aspect was a forerunner of Bond. Unfortunately, Fu Manchu played directly into the “Yellow Peril” archetype, a racist trope that depicted Asian characters as part of a cultural war to destroy the West. However, the series was extremely popular. Rohmer ended up writing 13 Fu Manchu novels before his death from the so-called (no, we couldn’t possibly make this up) “Asian flu” pandemic in 1959.

A clip from The Face of Fu Manchu with Christopher Lee (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Archive)

Fu Manchu’s story was adapted into films many times, including popular series in both the 1930s and 1960s (the latter of which featured Christopher Lee as Fu Manchu in five films). The character also made it to other media in various forms including radio and television; Fu Manchu was also featured in Detective Comics beginning in #17, which preceded the introduction of Batman by several issues. The evil mastermind’s comic licensing passed through a number of companies before the rights landed in the hands of Marvel (to be, as they say, continued).

During the late 1960s, an authentically Asian genre began to gain more popularity in the United States. In 1958, Runme and Run Run Shaw, part of the successful Shaw family of film producers, started a new production company, Shaw Brothers. Based in Hong Kong, the studio was built on the old Hollywood system; they contracted actors and would pair recurring casts with directors for different films. While the Shaw Brothers produced films in a variety of genres, their martial arts films began to break out in the 1960s.

At the same time, American audiences had been exposed to a taste of the genre via Bruce Lee. Lee played the title character’s crime-fighting partner, Kato, on The Green Hornet. The show only ran for the 1966-1967 season, but Lee became extremely popular, and a crossover episode with Batman further expanded his reach. Hornet was the first American TV program to showcase a martial artist of Asian ethnicity fighting in the traditional style. After Hornet, Lee tried to pitch his idea for a show featuring a wandering martial artist in the Old West; he called the concept The Warrior. Unfortunately, Lee’s idea was poached and turned into the American series, Kung Fu, which starred David Carradine; it ran from 1972 until 1975.

The final fight from The Big Boss (Uploaded to YouTube by Miramax)

Denied the chance to make The Warrior, Lee went to Hong Kong and began making a successful series of films for production company Golden Harvest. His first hit, 1971’s The Big Boss, was a worldwide success; it was released in the U.S. in the spring of 1973 as Fists of Fury. This was followed by The Chinese Connection (titled Fist of Fury in other markets) in 1972, and Enter the Dragon in 1973. Unfortunately, Lee had died just days before the release of Dragon due to a cerebral edema and adverse reaction to medication. However, his popularity and charisma helped set the stage for the Shaw Brothers films in America, of which a major one saw stateside release in 1973.

That was Five Fingers of Death (known in Hong Kong as King Boxer). Released in March of 1973, the film was widely successful and kicked the door open for 30 more martial arts films to get U.S. release in short order. The craze wasn’t lost on musician Carl Douglas; in 1974, he wrote a disco-flavored tribute song called Kung Fu Fighting. It hit #1 around the world (including the U.S.) and sold over 11 million copies.

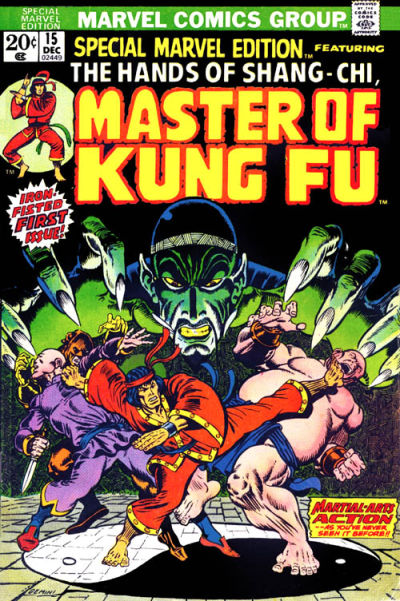

With the Bruce Lee and Shaw Brothers films in theaters and Kung Fu on TV in 1972, Marvel Comics saw an opportunity. They made a play to get the comic book rights to Kung Fu, but were foiled because the show was owned by Warner Communications, who also owned Marvel’s cross-town rivals, DC Comics. However, Marvel discovered that Rohmer’s Fu Manchu rights were up for grabs, so they acquired them to see what could be done with the material. Writer Steve Englehart and writer/artist Jim Starlin got to work. Introduced in Special Marvel Edition #15 in December of 1973, Shang-Chi headlined a feature titled The Hands of Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu. Shang-Chi was revealed to be the son of Fu Manchu, who would soon turn away from his father’s path of evil; an enormously skilled living weapon, Shang-Chi aligned himself with Denis Nayland Smith and a group of other spies to try to thwart his father’s various schemes.

Shang-Chi was instantly popular. Special Marvel Edition was retitled The Hands of Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu with issue #17, and the character was a lead feature in the newsstand magazine The Deadly Hands of Kung-Fu. Set squarely in the familiar Marvel Universe, Shang-Chi interacted with other Marvel characters and was the first in a parade of new martial arts-based protagonists, including Iron Fist, White Tiger (and the Sons of the Tiger), and Colleen Wing. Englehart and Starlin didn’t stick around long (Englehart moved to the likes of The Avengers, The Defenders, and Doctor Strange, while creating or co-creating characters like Valkyrie and Hellcat; Starlin created mainstays like Thanos, Mantis, and Drax the Destroyer, and the Infinity Gauntlet in his various cosmic books). However, Shang-Chi got an excellent new pair in the form of writer Doug Moench and artist Paul Gulacy (who drew their lead to resemble Bruce Lee more than a little bit). Moench would write the character for eight years, four years of which were drawn by Gulacy. The pair received critical acclaim and kept the spy-flavored series going long after the fad that birthed it had flamed out. The original series wrapped in 1983 with the death of Fu Manchu (who was seemingly killed when his own fortress collapsed on him). Shang-Chi retires to a simple life as a fisherman.

While the Kung Fu movie boom died out in the 1970s, the tropes were absorbed into anime, comics, and other genres of Hong Kong film, like wuxia, essentially a form of fantasy set in ancient China, where the heroes are so strong in the martial arts that their abilities defy belief (for example, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). And though Shang-Chi retired in the comics in 1983, he returned to the pages in the late 1980s to rejoin his allies and battle his (shock!) father, who survived his seemingly certain death years before. Shang-Chi stuck around comics, becoming a member of teams like Heroes for Hire and even The Avengers. When the rights to Fu Manchu lapsed, Marvel began applying retroactive continuity (updated explanations to tweak details of old stories), replacing the old problematic villain with a version of the character renamed Zheng Zu.

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Marvel Entertainment)

In 2004, when the nascent Marvel Studios began making their moves to acquire capital to produce a line of films, Shang-Chi was one of the ten original characters proposed. Over time, Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige would repeatedly express his desire to get to Shang-Chi, but also noted that the studio wanted to take care and avoid the pitfalls and stereotypes that could come with an Asian martial artist as a lead. Finally, at the 2019 San Diego Comic Con International, Feige introduced Destin Daniel Cretton as the film’s director; Cretton in turn announced actor Simu Liu as Marvel’s Shang-Chi. Feige also confirmed that Hong Kong film legend Tony Leung would be in the cast as classic Marvel villain, The Mandarin (and, in another update, apparently Shang-Chi’s father).

Shang-Chi has had a very long and winding journey from the page to the screen. It’s even more strange when you consider the prose roots of the character and the film craze that provided the catalyst for his creation. Some critics have gotten an early glimpse of the film, and the advance reviews are extremely positive; Collider calls it “an absolute triumph.” Perhaps the lesson of Shang-Chi is that while some stories and characters had periods of popularity when objectionable depictions might have been more socially acceptable, new generations have recognized how those stories might not have grown with their audiences. In the best hands, new interpretations can create heroes for underrepresented fans. Shang-Chi has a very real chance to do that because, after all, that cat is fast as lighting.

Featured image: PHOTOCREO Michal Bednarek / Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now