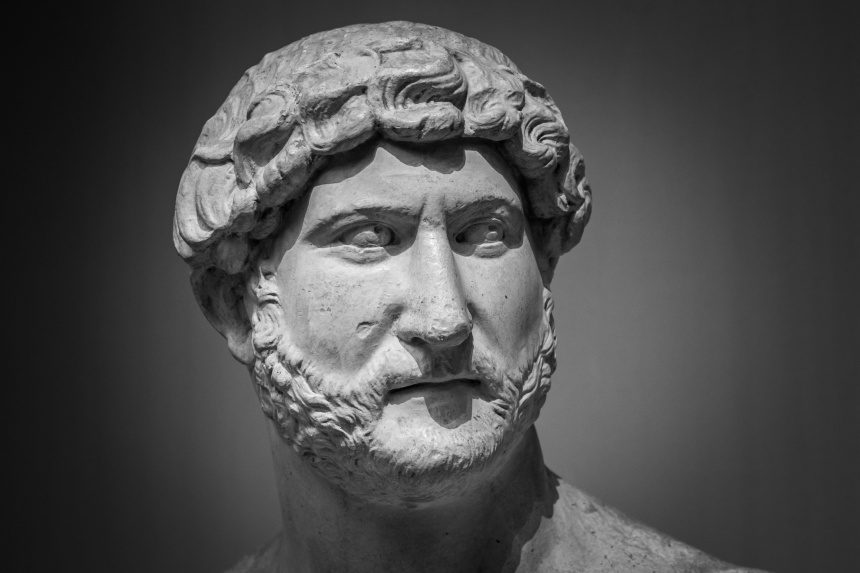

Ending wars has always been hard for great powers. Hadrian knew this. In 117 A.D., the new Roman emperor decided to withdraw his forces from an unwinnable war against the Parthian Empire.

Hadrian had inherited the conflict with Parthia — a large empire centered in what is now Iran — from Trajan, his imperial predecessor. Trajan’s generals resisted Hadrian’s withdrawal so forcefully that the emperor feared he might lose both his crown and his life. His ending of the war brought historical condemnation upon him for centuries.

It also was a decision that made Rome stronger.

The war began in late 113 A.D. after Parthian meddling in the Armenian kingdom that sat between the two empires gave Trajan a reason to attack. The emperor assembled as many as 80,000 troops at a forward base near the Armenian frontier and they advanced easily through Armenia, assuming complete control of that kingdom by the end of 114.

In 115, Trajan’s forces absorbed many of the smaller kingdoms occupying the highlands of what is now eastern Turkey and northern Iraq. Then, in 116, Trajan mounted a full invasion of the cities and farmlands situated between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers.

By the end of 116, Romans had occupied the famous city of Babylon and seized the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon (the ancient Persian capital, near present-day Baghdad). Trajan even erected a statue of himself in Parthian territory near the Persian Gulf. The Roman Senate voted to give Trajan the honorary title “Parthicus,” and Trajan celebrated the capture of Ctesiphon by issuing a gold coin that displayed two Parthian captives seated beneath a victory trophy. The coin carried the legend “PARTHIA CAPTA”: Parthia Captured.

But Parthia had not really been captured. Roman forces had swiftly occupied a great deal of territory without facing a large Parthian army. Parthian troops had instead withdrawn from the lowlands of Mesopotamia into the Zagros mountains and there began to organize a strong and effective response to the Roman occupation that would make Trajan’s new conquests ungovernable.

While Trajan was touring Babylon and musing about how he might have matched Alexander the Great’s conquests if he were a younger man, the emperor received word of Parthian-sponsored rebellions erupting in cities all along the Tigris and Euphrates. Trajan had to send three different troop contingents to fight against these rebels, with the emperor himself leading the division around Babylon. Then he received word that a Parthian field army was marching on the new Roman province of Armenia.

Although Roman armies recaptured most of the rebellious cities by early 117, the revolts persuaded Trajan to return authority in Armenia to a pro-Roman Armenian king and to place a Roman-backed Parthian pretender on the throne in Ctesiphon. Trajan planned to return to campaign more in Mesopotamia, but he suffered a stroke and died in August 117.

Hadrian took over the empire at this moment of crisis. It was true that Roman forces had won nearly every major engagement in the Trajan’s eastern campaigns. But the new emperor realized that Rome’s large and capable army could not continuously respond to local insurrections in the cities of Mesopotamia, much less attacks by a Parthian adversary able to melt back into mountainous regions where the Romans dared not follow them.

So, the anonymous author of the Historia Augusta wrote, Hadrian “relinquished all of the conquests across the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers.” He later quotes the new emperor as saying that “those areas that can not be defended, should be declared liberated” and returned to local control. Hadrian left the defense of these regions up to the allied governments Rome had just installed.

The Roman withdrawal happened very quickly. Hadrian officially took power on August 11. Roman forces vacated Dura Europos — a base on the Euphrates and likely one of the last places Roman troops left — by September 30. In a little more than a month and a half, Hadrian had pulled back from the two provinces of Armenia and Mesopotamia as well as the territory in southern Iraq that Trajan had claimed for Rome.

As Roman troops departed, the ally that Trajan installed as Parthian king in Ctesiphon saw his regime collapse. Hadrian saved face by placing the deposed monarch in charge of a smaller border kingdom, but it was clear to all that Rome’s postwar settlement of Mesopotamia had failed. “Thus it was that the Romans, in conquering Armenia, most of Mesopotamia, and the Parthians, had undergone severe hardships and dangers for nothing,” reflected Roman senator and historian Cassius Dio decades later.

Cassius Dio captures a sentiment that many of Hadrian’s contemporaries shared. Hadrian had to remove several of Trajan’s top generals after he became suspicious that their disapproval of his policies might induce them to rebel. Later Roman historians passed an even harsher judgement than Cassius Dio. Writing more than 200 years after Hadrian’s order to withdraw, the historian Festus claimed that Hadrian “returned Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Assyria” because he “envied Trajan’s glory.”

Hadrian’s answer to his critics remains instructive today. He did not apologize for withdrawing from the lands across the Euphrates. The Historia Augusta instead suggests that Hadrian elected a strategy of “reinstituting the approach of the earlier emperors” and “devoting himself to actions that maintained peace” across the empire. In Hadrian’s view, Rome needed to exit foreign quagmires and stop fighting wars of expansion so that it could focus on improving domestic conditions.

Hadrian devoted much of his 21-year reign to improving the lives of Romans within the empire’s boundaries. He put down internal rebellions that had erupted after Trajan’s foreign wars drained troops and resources away from the empire’s core provinces. Hadrian spent much of his reign traveling across the empire, repairing infrastructure, and building new public buildings. Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, the Pantheon in Rome, and the massive Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens are among his most famous infrastructure projects. Hadrian then advertised his achievements with a series of coins illustrating his arrival in each province, his restoration of its prosperity, and his departure.

It is unlikely that any of these achievements would have been possible had Hadrian decided to keep fighting the costly war he inherited. Hadrian’s retreat was not popular, but the emperor understood that Trajan’s war had to end before his own Roman renewal could begin.

Originally published on Zócalo Public Square. Primary Editor: Joe Mathews | Secondary Editor: Sarah Rothbard

Featured image: sculpture of the emperor Hadrian (Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now