This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

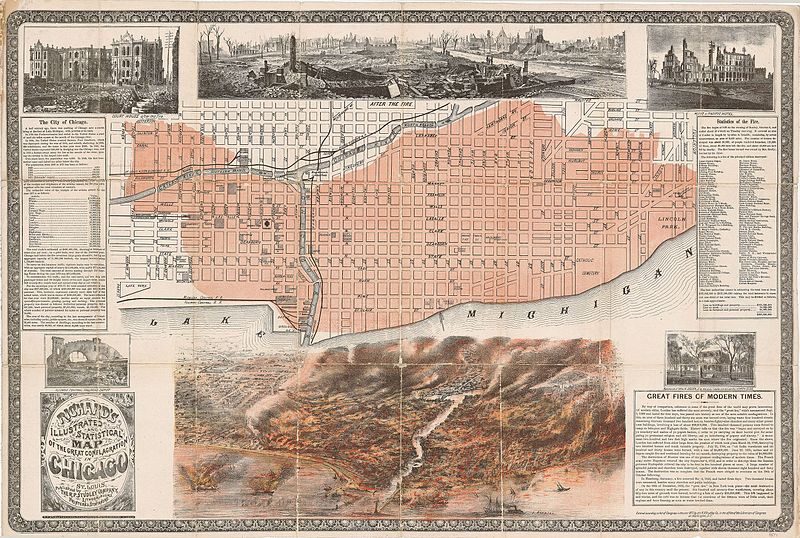

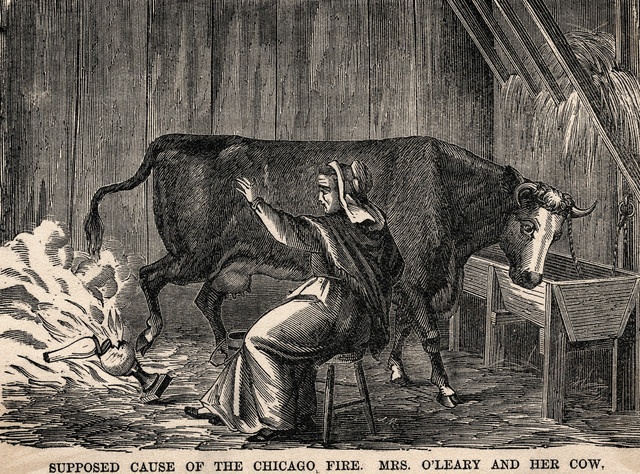

On the night of October 8, 1871, something near Chicago’s DeKoven Street started a fire that soon grew to epic and tragic proportions, raging for another full day (burning out, with the help of some rain, on the evening of October 9) and engulfing much of the rapidly blossoming metropolis in the process. By the time it was done the fire had destroyed roughly 3.3 square miles of buildings, killing around 300 residents and leaving more than 100,000 homeless. The city’s fledging Fire Department (with just 17 horse-drawn wagons, manned by just 185 firefighters, for the entire city) did its best but was quite simply overwhelmed by the scale of the blaze, helping make it one of the most destructive fires and disasters in all of American history. And as all American schoolchildren seem to learn (or at least as I certainly did in my school days), it was all thanks to Mrs. O’Leary’s cow.

Except that that’s almost certainly not the case. Despite relatively clear-cut historical evidence to the contrary, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow has remained a mythic origin point for this catastrophic fire. And that myth, like the larger question of what we do and don’t know about the fire’s origins, tells us a great deal about 19th century American prejudices, the complexities of our collective memories, and what we can learn from our shared histories and their gaps.

The fire did begin in the vicinity of the barn and home of one Catherine O’Leary and her family, but there’s no evidence that either she or her cow had anything to do with it. Moreover, those who have perpetuated that theory have repeatedly retracted it and/or apologized for doing so. High on that list is journalist Michael Ahern, a contemporary of O’Leary’s who wrote for the prominent paper the Chicago Republican at the time. In 1911, on the fire’s 40th anniversary, an anonymous former colleague of Ahern’s argued in a Chicago Tribune column (writing under Ahern’s name!) that Ahern and his friends John English and James Haynie had made up the cow story out of whole cloth.

Yet despite such admissions, the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow has persisted. Of course simplistic, mythic origin stories are appealing in general and quite common across American history; but this one in particular also seems impossible to separate from the period’s anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudices. Catherine O’Leary and her husband Patrick were working-class Irish Catholic immigrants to Chicago, part of a 19th century community that was becoming increasingly prominent in both the city overall and its power structure specifically. That community was thus was the target of both longstanding anti-Irish sentiments and renewed negativity due to those changing social and political trends, and blaming members of it for this most destructive moment in the city’s young history went a long way toward amplifying those narratives.

Those prejudices haven’t necessarily been a central factor in the myth’s enduring appeal across America and the subsequent 150 years post-fire (although I would argue the name “O’Leary” in the ubiquitous phrase “Mrs. O’Leary’s cow” does continue to serve as convenient shorthand for Irish American identity). But that’s precisely the problem: a fictionalized story that starts because of (at least in large part) stereotyping and bigoted attitudes gradually becomes instead an accepted, largely unquestioned shared mythos, one that gets taught to generation after generation of schoolchildren (and children outside of school to boot) as historic fact.

That’s one important collective takeaway from the popular story of the Great Chicago Fire. But all of that, like my phrase “the popular story” itself, also has a great deal to tell us about how history really works, far more often than we scholarly types might like to admit. Historians have generally agreed for well more than a century that the cow story is a fiction; but besides that familiar story’s simplifying appeal, another challenge in changing the narrative has been that the other possible explanations are likewise based on ambiguous and problematic sources and voices.

Perhaps a neighbor of the O’Leary’s named Daniel “Peg Leg” Sullivan started the fire while stealing milk from their barn. Sullivan offered vague and contradictory testimony about witnessing the fire’s origins in the city’s frustratingly slapdash and sloppy official inquiry into the disaster, and it seems possible that he was indeed a petty thief (and at least a far from upstanding neighborhood resident). But much of that is based on the controversial research of attorney and amateur historian Richard Bales, whose book The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow (2005) did help officially clear Catherine O’Leary’s name but makes a far from convincing case for Sullivan’s guilt in her place.

Maybe the blaze was instead the result of a craps game taking place in the barn, but that’s due to the unsubstantiated, secondhand deathbed testimony — ostensibly provided more than 70 years after the fire — of a man named Louis Cohn who claims to have been part of the game. Cohn, who was 18 in 1871 and went on to become a wealthy businessman by the time of his 1942 death, may have just been seeking to associate himself with one of the city’s most famous events — or the 1942 story may have simply been made up by someone else, since Cohn was no longer alive to contest it by the time it became public.

Or maybe the fire was caused by a meteor shower, as suggested by long-time Minnesota Congressman and amateur scientist Ignatius Donnelly in his book Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel (1883). Donnelly was prominent in Minnesota state politics and the post-Civil War Radical Republican community for decades, and delivered a speech at the Populist Party’s 1892 national convention in Omaha that became a touchstone for that influential new political party’s beliefs. But he was also an adherent of fringe pseudo-scientist beliefs, as illustrated by his 1882 book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World which argued that all civilizations were descendants of one mythic ancient culture.

The only thing we know for sure is that the Chicago fire was just one of many blazes that engulfed the Midwest on that October night. Fires devastated numerous communities across Michigan and Wisconsin, with more than 800 deaths in the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin alone. That largely forgotten detail in and of itself changes the story of the Great Chicago Fire, making it an exemplification of a larger national disaster rather than a singular event. But it gets us no closer to a definitive answer to what started Chicago’s fire — a telling question that, like Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, reminds us of the myths and ambiguities on which a great deal of our history rests.

Featured image: A Currier & Ives lithograph of people fleeing across the Randolph Street Bridge during the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 (Wikimedia Commons, Currier & Ives)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is the 150th anniversary of one of America’s worst tragedies regardless of how it was started. The loss of life, property and resulting homelessness is staggering. It’s still very shocking (to me) knowing the facts as we do know them, presented here in the first paragraph.

As you state in paragraph 2, Mrs O’Leary and the cow were NOT the cause of this tragedy per the clear-cut evidence to the contrary of the facts that were/are known, and may the record reflect that. The link in paragraph 3 regarding Michael Ahern shows he single handedly seems to be the largest factor in the creation of this damaging mythical folklore that still persists to this day.

This absolutely seems like has origins to the person or people that were either guilty themselves or knew of those who were. Completely wrong morally, ethically and legally to have been created as the needed “blame” and “answer” to what happened, it unfortunately worked as the deflection it was intended to be.

For school children (and adults) it’s almost a “cute” story because of the cow. Like a horse or dog it’s an animal most people like, and any thoughts and conversations end there. Since the ‘guilty party’ was a cow, it automatically means it was an accident with no guilty party, artificially shutting down the need for further discussion or investigation.

Tragedy on top of tragedy were all the fires per bottom paragraph that occurred in Wisconsin and Michigan that night that have been basically buried because of the Chicago fire lie. Historically, they should have been seen (then and now) as part of a much bigger picture on equal par of importance. Ambiguity may sound harmless (and often is depending on) but can also be very destructive and devastating with long reaching historical inaccuracies and consequences.