For many years, American illustration was male dominated. Women were prohibited from taking classes in drawing the human figure, for fear that they might be exposed to nude bodies. They were not admitted to the better art schools or offered the better art assignments. The father of American illustration, Howard Pyle, warned his students that women would not be able to combine a career in art with marriage.

But in the 1890s three talented young women — Jessie Willcox Smith, Violet Oakley, and Elizabeth Shippen Green — emerged to challenge this state of affairs.

The three met in Pyle’s art class in 1897 and quickly became friends. While the male students competed with each other, the women collaborated on some art projects and gave each other what they called “sympathetic companionship.” Pyle considered their work to be among the best in his class, despite his views about female art students, so he used his influence to help them get jobs illustrating for magazines.

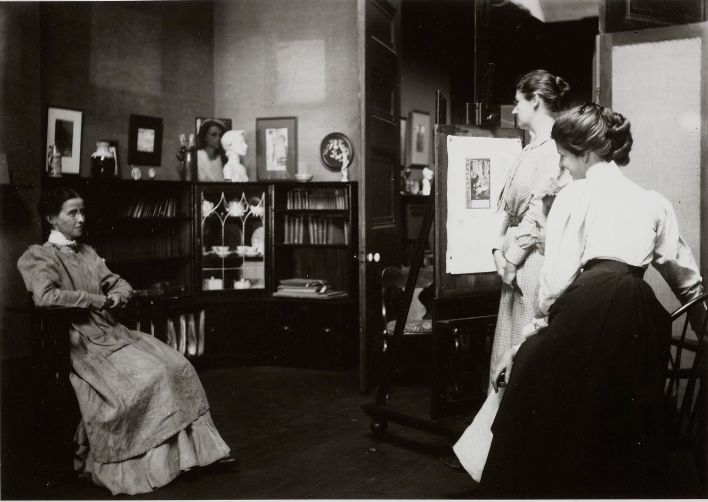

The three students got along so well they decided to move in together and share an art studio.

They found a roomy apartment with high ceilings and windows that provided ample light for painting. Located on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, the place was named “The Love Building” after the owner, Clement C. Love, who turned out to be a friendly and supportive landlord. The women were able to rent living and working space on the third floor for just $18 apiece per month, and Mr. Love was patient when the rent was a little late.

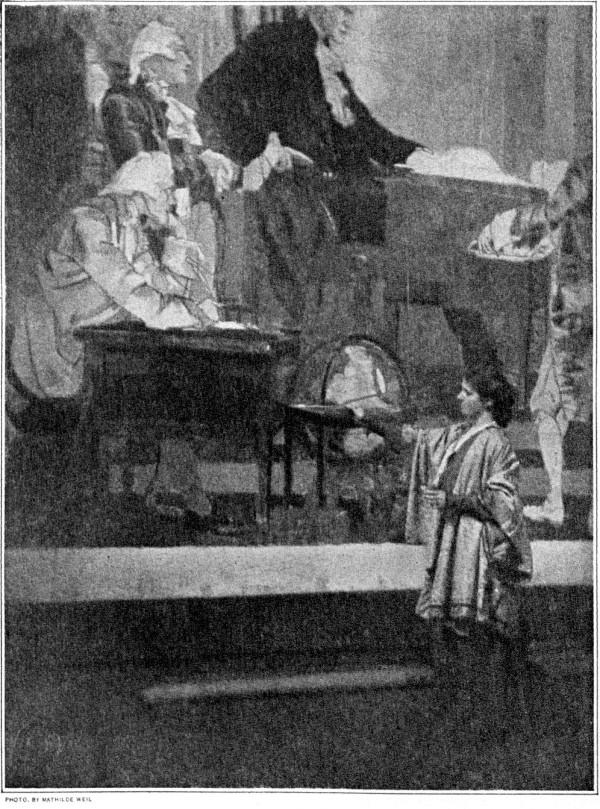

In the Love Building the women started out to make their dreams come true. They had good drawing skills and strong imaginations. Their pictures also demonstrated a sense of design, which was important for illustration in that era. They would dress up in costumes and pose for each other’s paintings. They would salute each other’s successes with teas and celebratory dinners.

They joined the first successful woman’s art organization in America. As they bonded in their new home, they began calling each other “sister” and developed pet names for each other.

Their reputations grew and new assignments began to flow from different sources. Smith and Oakley were commissioned to illustrate the book Evangeline, which became a critical success. That book was followed by commissions to paint covers for Women’s Home Companion. Elizabeth Shippen Green received assignments to illustrate for The Saturday Evening Post. Oakley painted for popular magazines such as Collier’s and The Century.

In her excellent book, The Red Rose Girls, Alice Carter wrote:

In the nineteenth century it was a widely held view that a close romantic friendship between two young women could keep a girl out of trouble while she waited for the right young man…. As Jessie, Elizabeth, and Violet shared their triumphs and failures and the everyday pressures of meeting editors’ demands and deadlines, their relationship with one another grew stronger.

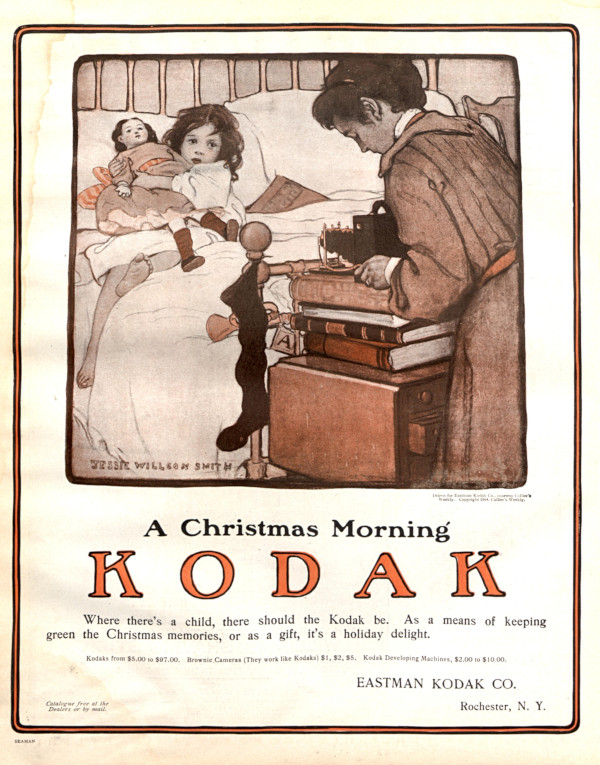

They could compete in a man’s world, but often they found their voice creating pictures from a woman’s perspective. Jessie Willcox Smith would become famous for her empathetic paintings of mothers, babies, and children.

This made her a natural choice for illustrating women’s magazines of the era, such as Good Housekeeping (for which she painted nearly 200 covers).

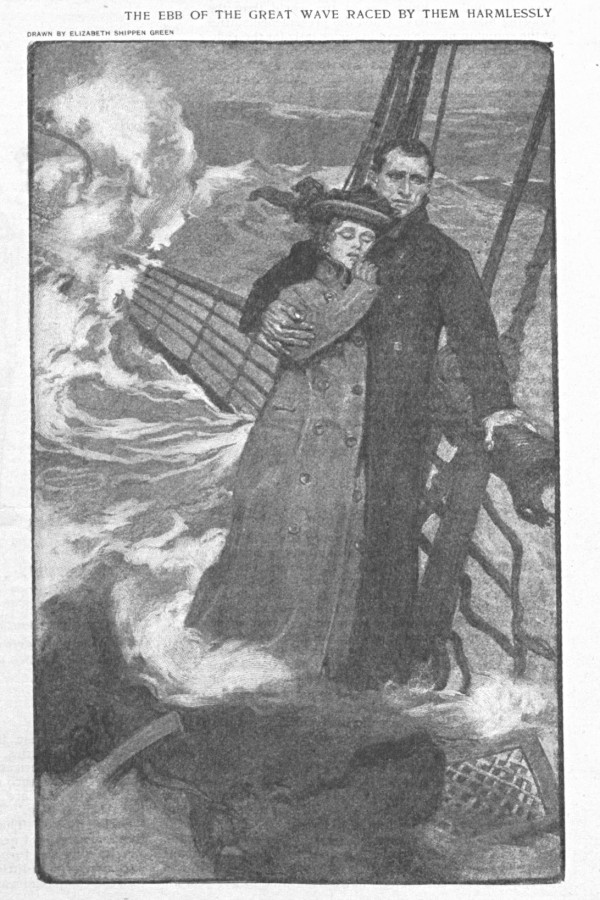

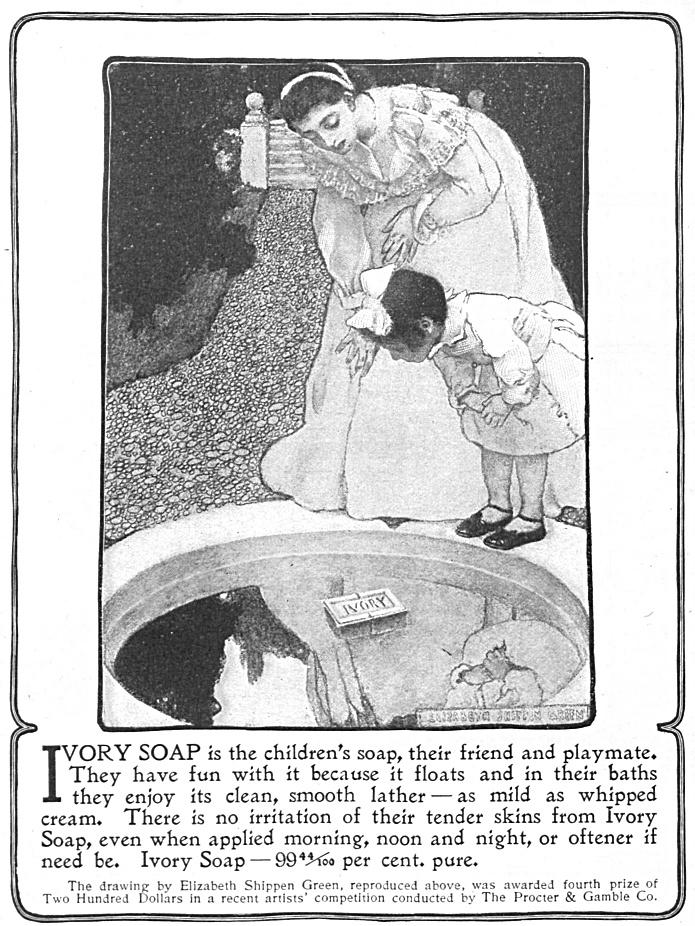

Elizabeth Shippen Green also painted many scenes involving women. Her illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post helped establish her reputation.

She eventually became widely recognized for her excellent use of color, and art directors went out of their way to reproduce her paintings in color at a time when color was expensive and most illustrations were still reproduced in black and white.

Violet Oakley started out painting illustrations, but with the passage of time she developed her own niche painting large murals, and for a time devoted her talent to stained glass windows.

The little art studio in the Love Building began to attract visitors and curiosity seekers. Reporters came to interview them about their success in a man’s profession. Art students came to ask for advice or seek inspiration. Friends came by to chat. To reduce the traffic, the young women posted a sign by the stairs, “Match-boys, Peddlers and Beggars Not Allowed in this Building,” but it didn’t seem to make much of a difference. It was time to leave the Love Building and find a larger place where they could work in peace.

By this time, the artists had become commercially successful. For example, Smith was being paid $600 by Scribner’s for her illustrations. The women no longer needed to scrimp to pay $18 per month rent or beg their landlord for a little extra time. They moved from the city to the country where they found a lovely estate, called The Red Rose Inn, built in the style of an English country farmhouse. It had beautiful gardens, a wicket gate, fireplaces, and a tea room. It was here that the trio continued their mature careers and became nationally known as The Red Rose Girls, a nickname given to them by their former teacher Howard Pyle. Newspapers as far away as Chicago called them “the three best known women artists in the country” and “the 3 Lady Musketeers of Art.”

The Red Rose Inn brought them many adventures, successes and even some heartbreak, but years later, Violet Oakley would recall in her autobiography that it “all began” in the Love Building.

In August 2021, the Love Building was designated as a historic site by the city of Philadelphia, honoring the place where the Red Rose Girls got their start. The Philadelphia Historical Commission found that the building was socially significant for its role in the history of art, illustration, and for the forces that the Red Rose Girls pioneered.

Featured image: Oakley, Green, and Smith toasting at the dinner table with a friend (The Smithsonian Institution Archive of American Art)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for writing this article; however, a simple mention of the CCRA, the nominator; and the author, myself, Oscar Beisert, would have been nice. Preservation work is poorly paid, stressful, time consuming, and, as you can see in this article, thankless. Happy Christmas.

Thank for this feature David, on these remarkable American female artists/illustrators. Elizabeth Shippen Green (in particular) was very varied in her artistic styles. The one in color has a Maxfield Parrish look to it. Her 1902 Ivory soap print ad is really beautiful, and I like how she drew the reflection in the water proving it really does float.

Very glad Howard Pyle admitted these women to take his art classes. Their obvious talent quickly took away any questions of that decision. It’s really good that they found the Love Building. The right place at the right time, eliminating a lot of struggles so they could reach their full potential. I was also glad to read (per your link) the building has been preserved as a historic site, becoming official just a few months ago by the city of Philadelphia.