New inventions and technologies have often been met with suspicion. People once believed that passengers in railway cars would suffocate or go insane. President Benjamin Harrison refused to touch the light switches in the newly electrified White House out of concerns of being shocked. Some people in the 1900s worried that telephones would electrocute them. And in the 1920s, the rise of radio broadcasting prompted a wave of radiophobia — a fear of radio waves.

The worry was understandable: the air was being filled with a powerful, imperceptible energy with then-unknown risks. While radio signals proved benign, other problems arose from the increasing reliance on radio-frequency (RF) transmission.

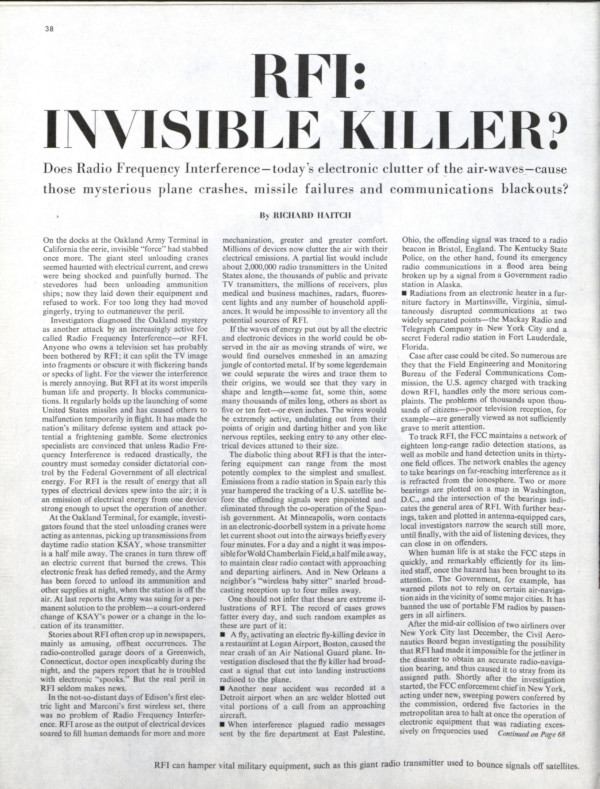

According to a 1961 Saturday Evening Post article, “RFI: Invisible Killer?,” radio signals from myriad devices frequently interfered with each other, often with serious risks:

• A fly, activating an electric fly-killing device in a restaurant at Logan Airport, Boston, caused the near crash of an Air National Guard plane. An investigation disclosed that the fly killer had broadcast a signal that cut into landing instructions radioed to the plane.

• Another near accident was recorded at a Detroit airport when an arc welder blotted out vital portions of a call from an approaching aircraft.

• When interference plagued the radio messages sent by the fire department at East Palestine, Ohio, the offending signal was traced to a radio beacon in Bristol, England. The Kentucky State Police found its emergency radio communications being broken up by a signal from a government radio station in Alaska.

• At Cape Canaveral, Florida, at least one missile maneuvered erratically when a woman taxi dispatcher in Austin, Texas, radioed instructions to a driver. The radio signal that guided the missile had a pitch nearly identical to the dispatcher’s voice. Nearly one in every five launchings at the Cape were delayed in the countdown stage by interference from a variety of sources to data-transmission channels.

The FCC, the Post reported, was working hard to keep radio-frequency transmissions within their assigned frequencies and power levels.

The concerns over RF hazards emerged again in the 1990s, when consumers feared their new cellular phones might cause brain tumors or other cancers. After several studies, the FDA reported “there is insufficient evidence to support a causal association between RFR exposure and [the formation of tumors].” And the FCC has found no scientific evidence of a link between wireless device use and cancer or other illnesses.

Anxieties over cell-phone use has recently risen again with the introduction of 5G technology. It operates at frequencies up to 30 gigahertz (GHz) and can carry ten times the data contained in 4G transmissions.

One team of researchers who has studied the effect of 5G say the principal effect of cellphone use is a rise in body temperature. As signals rise in frequency, as they do in the switch from 4G to 5G, the penetration of EM radiation drops. Professor Andrew Wood of the Australian Centre for Electromagnetic Bioeffects Research says of 5G signals, “the power levels involved in mobile and wireless telecommunications are incredibly low, which, at most, produce temperature rises in tissue of a few tenths of a degree. Picking up unambiguous biological changes is therefore very difficult.”

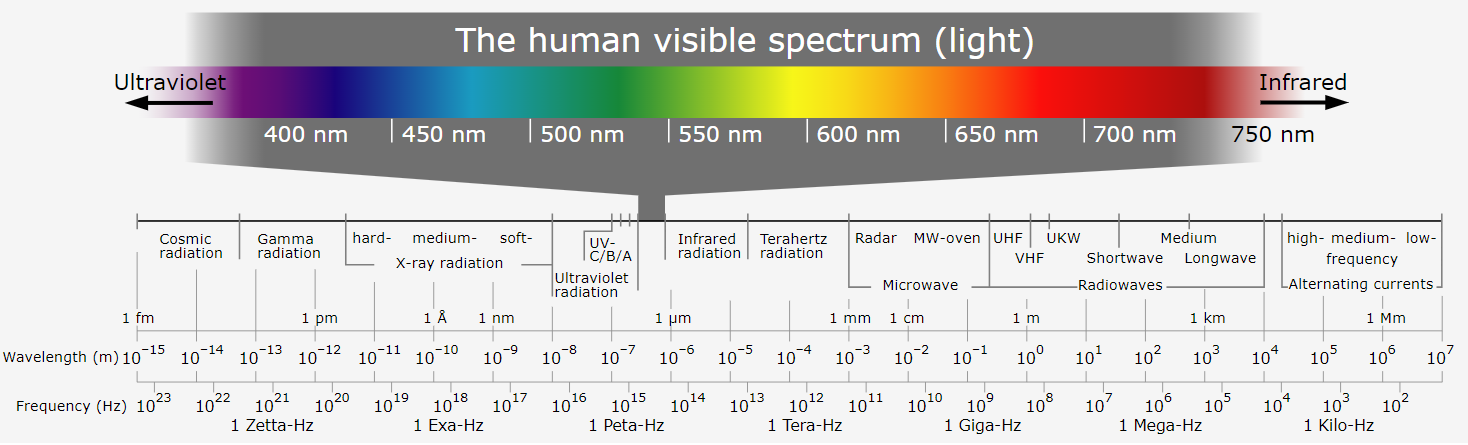

But fears of the entire range of electromagnetic radiation (which include radio frequencies) have only multiplied since our atmosphere has become busy with radio and TV broadcasts, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals, traffic from cell phones and cell towers, and the electromagnetic fields of power lines.

While some limited studies have raised concerns, none of the frequencies used by these systems have been proven to pose a serious health threat. Emissions in the EM spectrum between one and 1015 cycles per second cannot ionize molecules.

The higher frequencies, which start at ultraviolet light and include X-rays and gamma rays, can ionize molecules in nucleotides, which will alter DNA and may lead to cancer. And some studies has indicated a possible link between long-term EMF exposure and childhood leukemia.

Since the first atomic weapons were used in bombs, we’ve learned a lot about higher frequency radiation’s dangers (radioactive poisoning) and benefits (medical diagnostics and therapies.) Yet there is still much to learn about electromagnetic radiation — especially its potential for being weaponized.

In 2016, Americans at the embassy in Havana, Cuba, heard a strange noise they compared to buzzes or squeals, which preceded feelings of heat or intense pressure in their heads. This was sometimes accompanied by nausea and disorientation. Some of the victims were left dizzy or fatigued for months, and experienced lingering anxiety, cognitive difficulties, and memory loss. The University of Pennsylvania examined 40 people affected by the Havana Syndrome and found evidence of brain damage.

American diplomats in Russia had reported comparable experiences back in the 1970s. In 2018, similar cases were reported in Asia and central Europe, and this year in Berlin and Vienna.

At first, the reports were dismissed as psychosomatic symptoms; there was no technology known that could produce such sensations. But a panel of experts from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that “directed, pulsed radio frequency energy” was the most plausible cause. Had microwave radiation become weaponized?

Havana Syndrome is now being taken seriously. CIA Director William Burns says the CIA is redoubling its efforts to identify the source of the problem, which has claimed at least 200 victims.

He told NPR, “there’s probably about a hundred [incidents] in which my colleagues, my officers and family members have been affected.”

The difficulty is, as it has always been, identifying the who, what, where, and how of radiation illnesses. It would be possible to misread symptoms and ascribe a problem to some form of electromagnetic energy, while overlooking a more mundane solution.

According to one official, several members of the U.S. military reported to have experienced an attack similar to the Havana Syndrome. He added, “turns out they had food poisoning.”

The fact that people can’t tell whether it’s food or advanced weaponry that’s making them ill shows how much reason there can be for technophobia today.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Let us be clear, the only argument against the scientifically proven rise in gliomas and cellphone use is “We know ionizing radiation causes cancer, RF radiation isn’t ionizing radiation, ergo RF radiation doesn’t cause cancer” which is a truly absurd argument. That’s like saying “We know arsenic is a poison, mercury isn’t arsenic, so mercury isn’t a poison”