This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

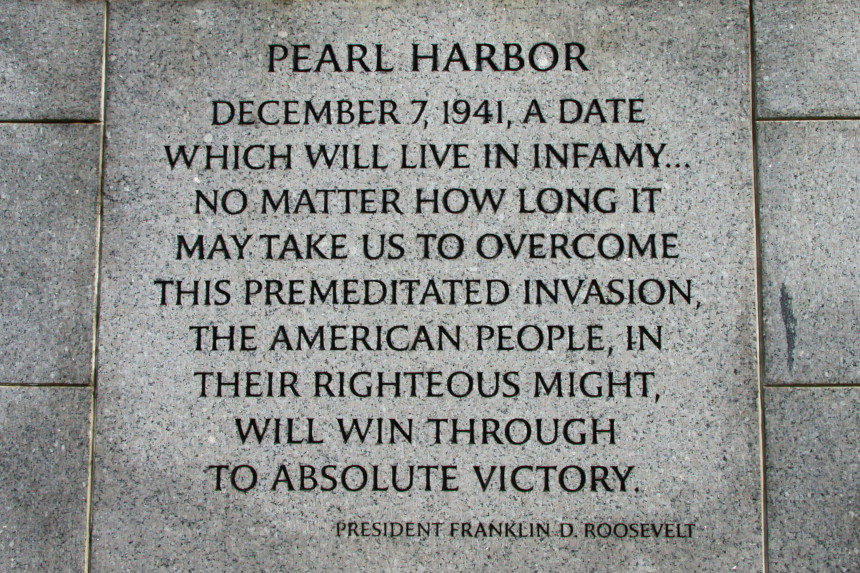

December 7 will mark the 80th anniversary of the Japanese surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, near Honolulu, Hawaii. Few individual events have been more influential on the international stage, from the subsequent U.S. entrance into World War II to the post-war Tokyo War Crimes Trial that punished Japanese leaders. Those kinds of legacies, as well as all the American lives lost in the attack, will undoubtedly be the focus of collective memories on this latest Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day, as they should be.

The aftermath of the attacks continued to play out in Hawaii in the days and months after December 7, 1941, however — and to involve many Hawaiian American individuals and communities beyond those stationed at the naval base. Too often forgotten in our narratives of the war is the crucial work of the Hawaii Territorial Guard, who embody the best of this diverse and inspiring American community.

As a U.S. territory Hawaii had a National Guard branch, but that force was federalized for the duration of the war, leaving the territory itself largely unprotected. As early as 10am on December 7, while the Pearl Harbor attack was ongoing, Governor Joseph Poindexter mobilized a territorial counterpart, known thereafter as the Hawaii Territorial Guard. Made up of individuals and communities from across the islands, this force would be answerable only to the governor and local authorities, making them more fully and uniquely tied to Hawaii.

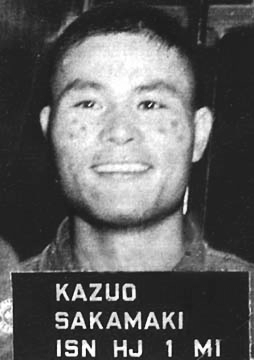

The Hawaii Territorial Guard was involved in the immediate aftermath of December 7, when they captured the first Japanese prisoner of war. While the bulk of the Pearl Harbor attack was undertaken from the air, the Japanese also sent five two-man “midget submarines” to raid the harbor; all five were sunk, and nine of their ten crew members killed. The tenth, Japanese sailor Kazuo Sakamaki, lost consciousness while trying to detonate an explosive device in his submarine and was washed ashore on Waimanalo Beach. He was found and captured there on the morning of December 8 by Hawaii Territorial Guard member and Native Hawaiian David Akui.

Sakamaki became the first Japanese prisoner of war held in the United States. His submarine was recovered and exhibited around the country as part of wartime propaganda and fund-raising efforts, and now resides at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Texas. Shortly after the war’s end, Sakamaki wrote a thoughtful and self-reflective memoir, I Attacked Pearl Harbor (1949). He had become thoroughly dedicated to pacifism during his time as a POW, and the memoir was thus as much an argument against war as a reflection on his wartime experiences. Less is known about Akui, who was just 20 years old on that fateful morning on the beach. But his exemplary military service continued throughout the war, including time with the famous 5307th Composite Unit (known as “Merrill’s Marauders”) that experienced some of the Pacific Theater’s most difficult combat against Japanese forces in the jungles of Burma.

As the U.S. entered into combat across the Pacific Theater in the months after Pearl Harbor, the role and importance of the Hawaii Territorial Guard in protecting this vital American territory was likewise amplified. One of the most sizeable cohorts to join the HTG after the attacks were 155 Japanese American college students at the University of Hawaii, part of the university’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program. They were issued Springfield rifles and assigned to guard hospitals, power plants, food storage centers, and other potential sites for further Japanese attacks, a very real possibility in this uncertain and frightening post-Pearl Harbor period (during which the island was under martial law).

Unfortunately, for many white Hawaiians and Americans those uncertainties and fears became linked to longstanding anti-Japanese prejudices, the attitudes that would shortly thereafter produce the Japanese Internment policy. In January 1942 the HTG was disbanded and the Japanese American students were sent home; the HTG was reformed the next day without any Japanese American members. As Ted Tsukiyama later reflected, “I think we cried. Just, you know, frustration, anguish, disappointment, the feeling of rejection…that you are distrusted by your country.” His comrade Shiro Amioka put it more bluntly, “to see Japanese Americans with rifles, with live ammunition, was inconceivable to some people up there.”

The students refused to accept this distrust and discrimination as the final stage in their wartime service, however. Working with one of their main mentors and allies, the Chinese American YMCA executive Hung Wai Ching, the students drafted a petition to Hawaii’s military governor, Lieutenant Governor Delos Emmons. In it they wrote, in a stirring paragraph worth quoting in full,

We, the undersigned, were members of the Hawaii Territorial Guard until its recent inactivation. We joined the Guard voluntarily with the hope that this was one way to serve our country in her time of need. Needless to say, we were deeply disappointed when we were told that our services in the Guard were no longer needed. Hawaii is our home; the United States, our country. We know but one loyalty and that is to the Stars and Stripes. We wish to do our part as loyal Americans in every way possible and we hereby offer ourselves for whatever service you may see fit to use us.

Emmons accepted their petition, and the students formed a group called the Corps of Engineers Auxiliary — a community known to themselves and eventually throughout Hawaii as the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV). They would perform countless services on military bases and around the islands over the next year, much of it the construction and engineering work necessary to build and sustain military preparedness. But the VVV also pooled their paychecks to purchase war bonds, built furniture for preschools, donated blood, and created summer and sports programs for local youth, becoming a true fixture throughout the community.

Moreover, the VVV would become the origin point for the Japanese American military units that would serve with such bravery and distinction throughout the remainder of the war. Japanese Americans were not allowed to serve in the U.S. armed forces for the first year of the war, but in December 1942 Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy (previously a proponent of internment) toured Hawaii with Hung Wai Ching as his local escort; Hung made sure that McCloy met members of the VVV, and a few weeks later, in January 1943, the War Department reversed its policy and announced plans to create two all-Japanese American combat units.

The Pearl Harbor attack was one kind of wartime tragedy, and what happened to America’s Japanese American citizens and communities after the attack and throughout the war was a second. Offering an alternative to those divisions and discriminations are the actions of these members of the Hawaii Territorial Guard, individuals and communities who modeled the best of this diverse island and of our equally diverse and inspiring American identity.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now