This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The one-year anniversary of the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol in Washington offers an opportunity to remember not just that unprecedented and shocking event, but the echoes throughout the year that followed. Another striking event took place last January that would also echo into the remainder of 2021: the Martin Luther King Jr. Day release of President Trump’s 1776 Advisory Commission’s Final Report on American historical education, a document that attacked educators for presenting an insufficiently positive perspective on America’s revolution, founding, and ideals.

Both of these events have something in common: prominent narratives of a very particular form of patriotism, as illustrated by a pair of telling quotes. In Andrew McCormick’s January 7th Nation article on the insurrection, one of its participants is quoted as saying, when the police begin to fire tear gas into the crowd, “This is not America…They’re shooting at us. They’re supposed to shoot BLM [Black Lives Matter], but they’re shooting the patriots.” And the 1776 Report defines its mission as “restoring patriotic education that teaches the truth about America,” in opposition to educators who “generate in students and in the broader culture at the very least disdain and at worst outright hatred for this country.”

These statements embody what I would call mythic patriotism, the most divisive and destructive of the four types of patriotism I discuss in my book Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism (2021; the book’s other three types, all in their own ways more positive, are celebratory, active, and critical). As I define it, mythic patriotism is a form of patriotism that creates and celebrates a mythologized, white supremacist vision of American history and identity, and which uses that vision of the nation not only to exclude those American communities and cultures that are not part of that myth, but also to attack as unpatriotic and even un-American those Americans who are not willing to uncritically celebrate that myth.

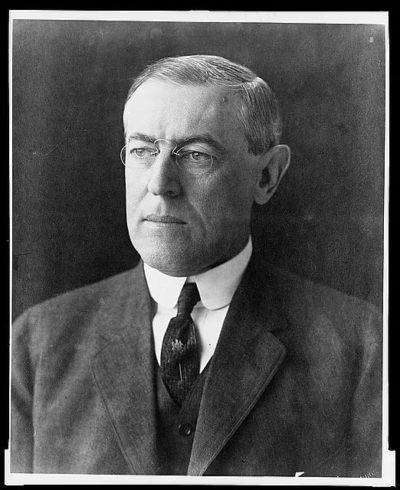

If we examine one particular century-old moment when mythic patriotism was most central to American politics and society, we can see many of the same divisive and destructive elements that were embodied by these January 2021 events. One particularly prominent such element is a belief that American ideals and identity are under attack from unpatriotic forces against which all patriotic Americans must fight back. In his December 1915 State of the Union address, President Woodrow Wilson expressed that belief clearly, arguing that “There are citizens of the United States, … born under other flags but welcome under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life” and “urging [Congress] to do nothing less than save the honor and self-respect of the nation” by passing laws to counter these threats.

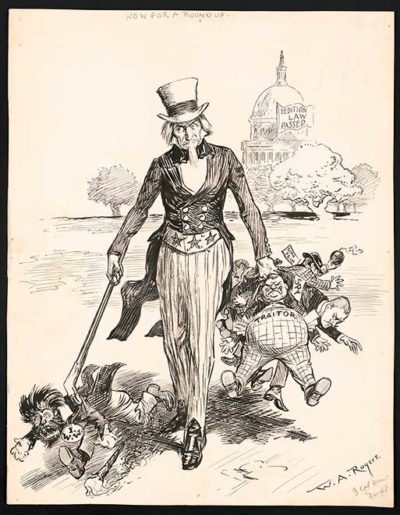

After extensive debate Congress did pass two such laws, the 1917 Espionage Act and 1918 Sedition Act. Today, these laws, which targeted countless American communities for arrest and even deportation, are considered among the most extreme and destructive in U.S. history. The Sedition Act especially exemplifies the idea that critics of American myths and symbols are unpatriotic and un-American, as it made illegal “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States … or the flag of the United States.” And it was used to target not simply “spies” or other such perceived threats, but anyone whose visions of American history and identity were deemed “seditious” — as was the case with Jewish immigrant and film producer Robert Goldstein, whose silent film The Spirit of ’76 (1917) was seized by the government for portraying the English (America’s wartime allies) too harshly and who was sentenced to ten years in prison. At the sentencing, Judge Benjamin Bledsoe told Goldstein, “Count yourself lucky that you didn’t commit treason in a country lacking America’s right to a trial by jury. You’d already be dead.”

The anti-immigrant sentiments expressed by Wilson and contained in these laws would become part of another layer to the era’s mythic patriotism: its definition of a foundational, white American identity that must be protected from the threatening changes represented by non-white and immigrant communities. In a speech on the Senate floor supporting the 1924 Quota Act, which limited immigration and banned all immigrants from Asia, South Carolina Senator Ellison DuRant Smith expressed that mythic patriotic vision clearly:

We have in America perhaps the largest percentage of any country in the world of the pure, unadulterated Anglo-Saxon stock…and it is for the preservation of that splendid stock that has characterized us that I would make this not an asylum for the oppressed of all countries…We do not want to tangle the skein of America’s progress by those who imperfectly understand the genius of our Government and the opportunities that lie about us. Let up keep what we have, protect what we have, make what we have the realization of the dream of those who wrote the Constitution.

Creating a discriminatory annual quota system for new arrivals, one that entirely excluded Asian immigrants and severely limited Southern and Eastern European ones (Greece, for example, had an annual quota of just 100 arrivals), this first comprehensive national immigration law led to the only period in American history when the nation’s foundational and evolving ethnic diversity decreased.

Mythic patriotism likewise depicts any critical perspectives on the nation as equally threatening and unpatriotic, including those reformist perspectives that motivate activist and progressive protest movements, both today and 100 years ago. In a February 1920 speech at a Baltimore church, the prominent Methodist Episcopal Bishop William Quayle used mythic patriotism to attack the era’s labor movement, claiming that “Labor’s threat is a challenge against all we have and are in government, and as such it is our duty as American citizens to accept the challenge and in our strength rise up and crush the foe to our most cherished ideals.” Such attitudes would lead directly to the National Association of Manufacturer (NAM)’s tellingly named “American Plan,” a 1920s policy through which NAM businesses employed armed “patrols” to attack striking workers and other labor activists.

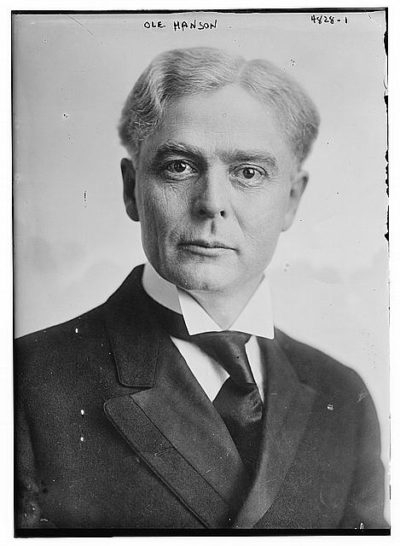

From this mythic patriotic view, any protest and critique that challenges American myths exists entirely outside the nation’s ideal community. Just as it often is today, a century ago that critical perspective was often attacked with shorthand terms like “socialist.” During a January 1919 general strike in Seattle, the city’s Mayor Ole Hanson argued that “the time has come for the people in Seattle to show their Americanism.” Hanson overtly equated not just the striking workers but all who would protest American inequities with radical, hostile foreign entities such as the newly created Soviet Union, and would expand on that argument in a book entitled Americanism Versus Bolshevism (1919). Later that year, President Woodrow Wilson called the September Boston police strike “a crime against civilization,” illustrating how mythic patriotism turns critique and protest into the enemy that requires patriots to battle for nothing less than the nation and world.

That mythic patriotic battle requires soldiers willing to fight for this vision of the nation and against its perceived enemies: on the steps of the Capitol, on the streets against “BLM,” in state legislatures and educational commissions, everywhere that those who oppose this particular narrative of patriotism can be found. As we mark these January 2021 anniversaries, it’s a good time to remember the ongoing effects of such mythic patriotic conflicts, on all of us.

Featured image: Pro-Trump insurrectionists rally at the U.S. Capitol building on January 6, 2021 (Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now