In 1933 Elmer Simms Campbell was a young, unemployed African-American man living with his aunt in a small rear apartment on Edgecombe Avenue in New York. This is the story of what happened the day opportunity knocked on that apartment door.

Campbell was born in St. Louis in 1906, but his father died when Campbell was four and the family moved to Chicago. There, Campbell went to work as a messenger boy and later found work as a waiter on train dining cars, but his dream was always to become an artist. He took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and won a few school prizes for his drawing. He even sold an early cartoon to The Saturday Evening Post, but could not find lasting work.

As Campbell told his biographer for the book, We Have Tomorrow, he learned important lessons about being an artist while serving tables on those trains:

I learned from my fellow waiters how close man can be to his fellow men. After this discovery my character began to develop and I began to paint and draw people as they really looked. Oh, I could always draw, but I was a failure as an artist till I became a successful dining-car waiter.

While he was working on trains, the enterprising Campbell continued to draw in every spare moment. “Between meals I spent my time making caricatures of the passengers as well as of the other waiters and the steward,” he said.

In 1929 Campbell got off the train in New York and moved in with his aunt. He tried to find work as an artist but recalled, “I didn’t catch on right away, by any means. I wore out a lot of shoe leather before I found a job. Even then it was nothing to get excited about.” Though he couldn’t find work, he continued to invent his own imaginative projects.

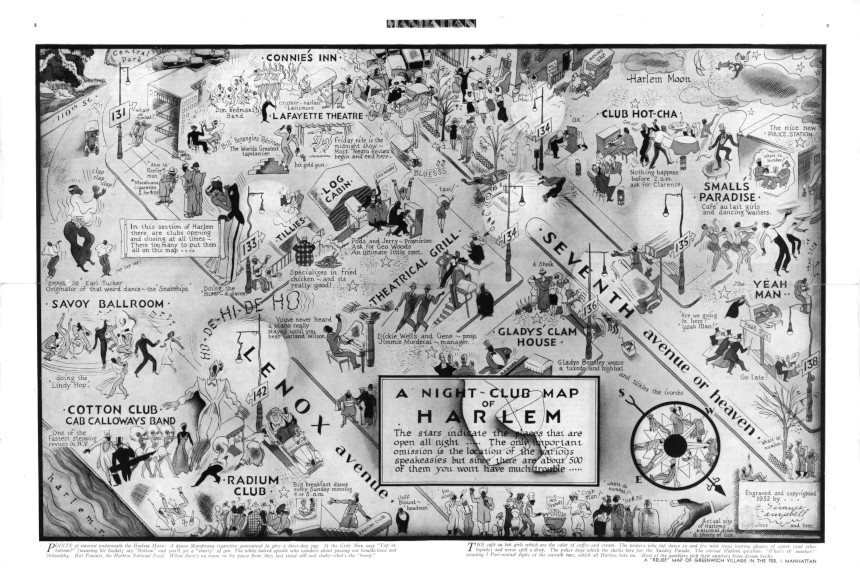

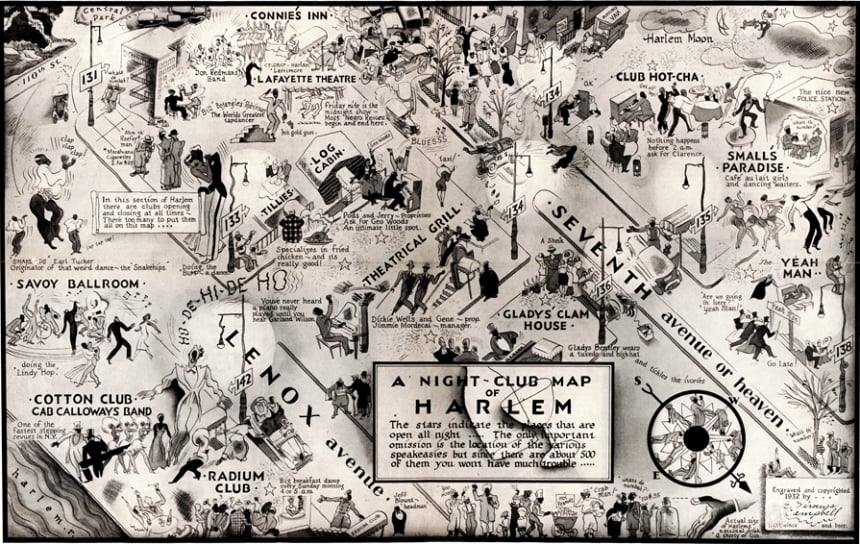

For example, in 1932 he drew a large cartoon called “A Night-Club Map of 1930s Harlem,” with his observations of the various clubs and night life in Harlem during the now famous Harlem Renaissance. He drew Cab Calloway singing at the Cotton Club, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson dancing at the Lafayette Theater, and other landmarks and celebrities of African American culture.

In 1933, Campbell and his aunt were scraping by when a man climbed the rickety steps up to Campbell’s flat and knocked on the door. The man, Arnold Gingrich, announced that he was starting a brand new magazine and was looking for a cartoonist.

Gingrich was the co-founder of Esquire magazine, a lavish, large format, premium magazine for men, unlike any previous magazine. It would be full color and printed on quality paper stock. It would sell for 50 cents per copy at a time when The Saturday Evening Post was selling for a mere 5 cents. It would contain full page color cartoons as well as stories by the top writers of the day, including Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Mann and John Dos Passos.

The first issue had just come out and was a striking success. It immediately sold out and the public was clamoring for more. Now Gingrich had just one problem: he needed an artist to fill all those blank pages.

Author George H. Douglas described the situation in his book, The Smart Magazines:

[Gingrich] hadn’t the slightest idea where he was going to find cartoons or other drawings in color to fill up this space…. cartoons were especially troublesome: American cartoonists weren’t working in color since such work wasn’t being bought by commercial magazines, especially in these depression years.

Gingrich had already contacted every prominent cartoonist in New York but couldn’t find a suitable artist willing to gamble on the new publication. He approached a well-known cartoonist named Russell Patterson,

but Patterson laughed at the figure of $100 a feature, which Gingrich mentioned as what Esquire was able to pay. Patterson also confirmed that no other well-known commercial illustrator would be willing to help out at such prices – writers, it would seem, were going to be easier to come by than artists.

As Gingrich left, Patterson volunteered that he did know of a talented “colored kid” who couldn’t get a job because he hadn’t been able to get past the receptionists to show his work. Patterson said that if Esquire “was not afraid to cross the color line” to hire an African-American artist, he might fit the bill. The “colored kid” was Campbell.

When Gingrich tracked him down at his aunt’s apartment, Campbell was desperate for a job and Gingrich was desperate for a cartoonist.

As soon as Gingrich saw Campbell’s sample drawings, he knew they were the answer to his prayers. He collected the samples and took them back to Esquire’s office, leaving a down payment of $100, which was more than Campbell had been paid for anything in his life. As if that weren’t enough, he promised Campbell that the new magazine would be giving him plenty of work in the future.

Gingrich returned with the co-founder of Esquire. The two men assured the disbelieving Campbell that they were ready to make a serious commitment to him and his work.

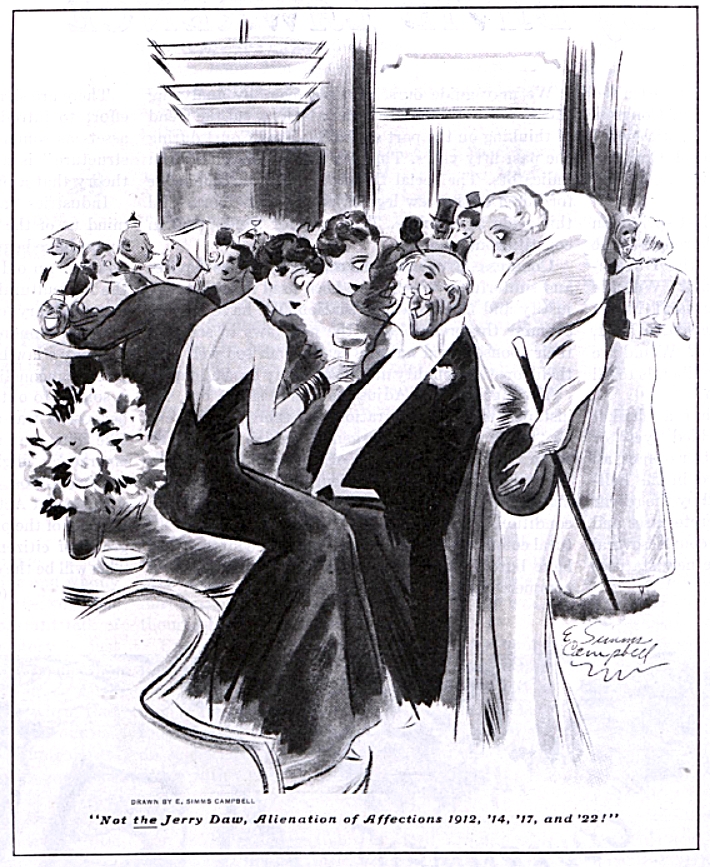

Soon Campbell was named the art editor for Esquire. His work appeared in every single issue of Esquire from 1933 until 1958. Esquire turned out to be the perfect showcase for Campbell’s talents. His role expanded beyond the cartoon pages; he designed the mascot “Esky,” who soon became the symbol of the magazine; and he illustrated fashion and style articles, covers, stories, and other material. As Douglas reported, “as much as anyone else [Campbell] established the magazine’s visual style.”

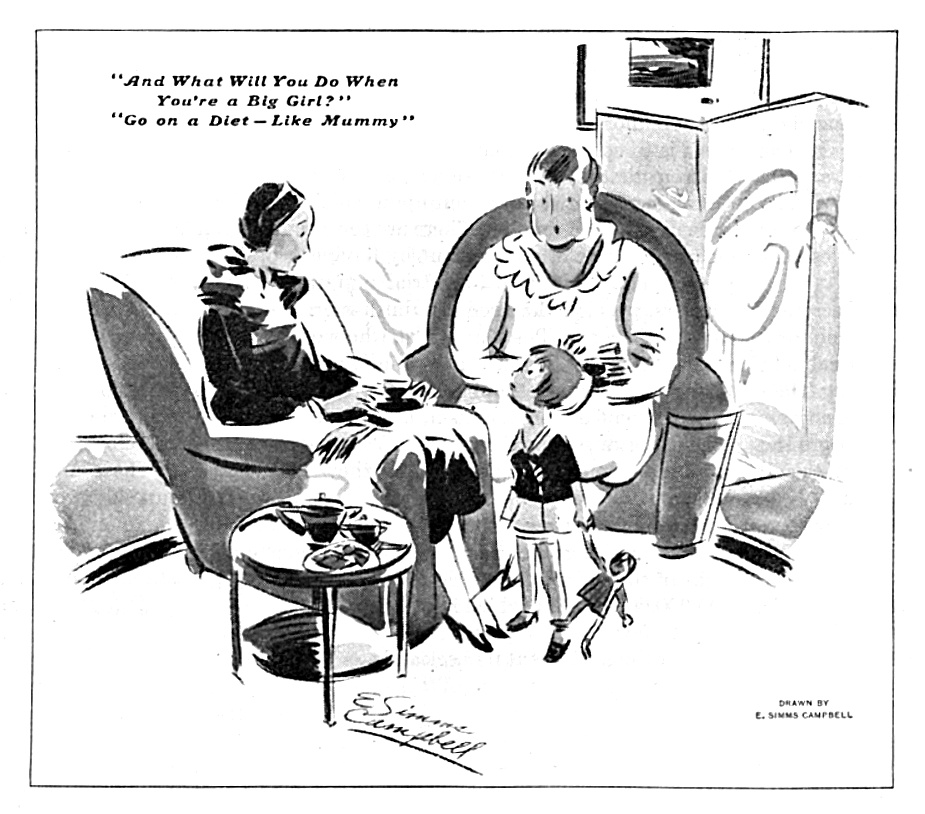

More than that, his role with Esquire exposed him to a huge audience and gave him instant legitimacy with other publications. His art reappeared in the Post:

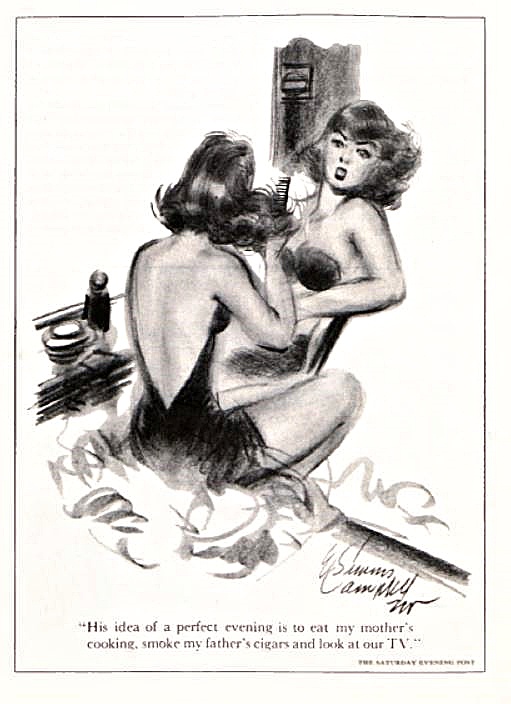

His work soon appeared in The New Yorker and Life magazine. He started a nationally syndicated comic strip called Cuties and also did advertising art. Campbell became so busy that he had to turn away work. He mounted a calendar on his drawing board to keep track of all his deadlines.

Campbell got married and moved to a very nice home in White Plains, New York where he and his wife Constance raised a family together. Constance helped out by modeling for his illustrations.

One advantage of being an illustrator in the early days of the 20th century was that the reading public had no way of knowing whether a picture was made by a male or female artist, or a white or an Asian or an African-American artist. If an artist mailed artwork to a magazine and the magazine accepted it, an artist might escape some of the prejudices that afflicted other jobs.

With his fame and fortune now secure, Campbell was able to use his art to openly celebrate his African-American identity. His ” Night-Club Map of 1930s Harlem” became a culturally important document, reproduced in several books, from Ken Burns‘s documentary Jazz to the autobiography of Cab Calloway by Cab Calloway and Bryant Rollins (T.Y. Crowell, 1976). It was displayed by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington and National Geographic magazine, and is now in the permanent collection of the Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

In 1942, his hometown paper, The St. Louis Star-Times, ran a major article about Campbell’s return to give a speech, saying “The St. Louis Negro community this week will celebrate the return of one of its favorite sons: E. Simms Campbell.” Campbell was using his fame and prestige to raise funds for a Negro People’s Art Center, where “young Negroes will have an opportunity to receive… the kind of formal art instruction that was denied Negro boys and girls of Campbell’s generation.”

Featured image: Campbell’s “A Night Club Map of Harlem” (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Outstanding article.

What an incredible success story, overcoming so many roadblocks simply because of his race. I admire how he cleverly utilized any spare time on the train (as a dining car waiter) refining his craft and techniques sketching pictures and caricatures of the various people on board.

It’s interesting and very fortunate how he met Arnold Gingrich as he was launching Esquire and realized he had the perfect artist in Mr. Campbell. He even drew ‘Esky’ that used appear in the circle over the ‘i’. It’s wonderful how he later used his fame and celebrity as an artist to help African-Americans receive the kind of formal art instruction he and his generation had been denied, due to race.

Getting to some of the art itself depicted here, it’s incredible. You can really tell the 30’s had their own look, distinctively different from the 20’s. Very visible in the 1933 cartoon. Of course these WERE the wealthy of the time; not the average American suffering from the Depression.

Love the sexy ’59 cartoon at the bottom which shows how varied his styles were. I can see why he was popular with Esquire during its heyday. It has an Alberto Vargas flavor to it, even if toned down. I wonder if he ever painted for Playboy? At least they finally knew when to call it a day; Esquire doesn’t. It’s terrible, and has been for decades.