In the neverending debate surrounding the question of the greatest film of all time, a few movies always rise to top of the leader board. There’s Citizen Kane, of course, and Casablanca. Seven Samurai gets plenty of mentions, as do more comparatively recent entries like The Shawshank Redemption and Do the Right Thing. But since its debut 50 years ago, one particular film has remained an essential part of that discussion. A film that’s just as much about family as it is about crime, a movie that says things about human nature even as it says things about the American experience, The Godfather succeeded beyond the expectations of its time. Based on a book that wasn’t even completed when the film rights were secured by Paramount, The Godfather changed the perception of organized crime dramas while also having a major impact on cinema itself.

One of the most compelling elements of film’s legacy is that it is beloved by disparate groups of people. Embraced equally by critics and audiences, it was praised for its cinematic greatness even as it raked in the box office. Americans adopted its extremely quotable screenplay into popular vernacular, so much so that offhand quips like “Leave the gun; take the canoli” or “Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes” are almost universally understood. Whether it was for its themes of family and morality or the intense craftsmanship on display, The Godfather simply reached people across cultural and generational lines.

The movie’s greatness was recognized immediately. Writing for The New Yorker at the time of the film’s release in March of 1972, Pauline Kael wrote that “[Coppola] has made a movie with the spaciousness and strength that popular novels such as Dickens used to have.” A Vanity Fair piece from 1999 indicated that legendary director Stanley Kubrick thought The Godfather “was possibly the greatest movie ever made and certainly the best cast.” And the great film critic Roger Ebert wrote that “Although the movie is three hours long, it absorbs us so effectively it never has to hurry. There is something in the measured passage of time as Don Corleone hands over his reins of power that would have made a shorter, faster-moving film unseemly.” The Godfather was a genuine cinematic event, and everyone knew it.

It all started with Mario Puzo, who wrote the book on which the movie is based. Born in 1920 in the Manhattan neighborhood of Clinton, better known as Hell’s Kitchen, Puzo was the son of Italian immigrants. He saw action in World War II as part of the U.S. Army Air Forces. After the war, Puzo graduated from City College of New York. He was selling short stories by 1950, and published his first novel, The Dark Arena, in 1955. In a move that he would later echo in The Godfather, Puzo made the main character of that first novel a veteran, like himself. He would return to his wartime experiences as he wrote for men’s pulp magazines in the ’60s. Before the end of that decade, he’d started writing his signature work.

In early 1968, a mutual acquaintance worked out a meeting between Puzo and Robert Evans. An actor turned producer turned production vice president at Paramount, Evans had been busy turning around the fortunes of the studio. By the time the two men had their sit-down, Evans’s Paramount had already struck box office gold with Barefoot in the Park and was weeks away from filling theaters with The Odd Couple and Rosemary’s Baby. Paramount wasn’t out of the woods, but Evans was viewed as a creative with a hot hand.

In Evans’s 1994 memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture, the producer revealed that he and Puzo bonded over a shared love of gambling, but that the writer was in a tight financial spot because of his habit. Puzo shared a few dozen pages of a novel in progress, one that he described as “an inside story on the boys.” By “the boys,” he meant organized crime. The working title was Mafia. Evans optioned the unfinished novel for $12,500 before the meeting was even finished, but the producer hadn’t been expecting much out of the book. By his own admission, “I looked at [the option] as a gift … one gambler helping another gambler out of a heavy muscle jam.”

Over the course of the next year, Mafia evolved into The Godfather. When it landed in stores in March 1969, the novel immediately captured public attention. A runaway hit, it sold more than nine million copies in its first two years of release, spending 67 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list. The novel literally changed the American vernacular, popularizing Italian terms like consigliere (advisor), omertà (the code of loyalty and silence among the Mafia), and Cosa Nostra (literally “our thing,” the phrase that insiders used to refer to the organization). The book’s success helped make Evans look good to the board at the studio; making an acquisition for that kind of moneymaker before the novel was even finished made the producer look like a visionary. But what Evans really needed was a director.

With Puzo on board for the screenplay, finding the right director was a necessity. Evans soon found himself contending with problems in two areas: Director after director was passing on the project, and Paramount’s distribution team didn’t even want to put it out. It turned out both problems had a similar origin. The various directors that the studio had approached, including Arthur Penn and Elia Kazan, were afraid of making a picture that would “romanticize the Mafia.” On the distribution side, their reluctance to make the movie was based almost entirely on the fact that recent movies about organized crime just hadn’t made much money.

Determined to make The Godfather the exception to that poor run, Evans and fellow executive Peter Bart studied “every [gangster] picture made in the last twenty years” to “see why they didn’t work.” Evans and Bart determined that a major factor in the failure of the previous films was the complete lack of Italian or Sicilian talent behind them. Evans reasoned that the film would have to be authentic or, in his words, “ethnic to the core. … That’s what brought the magic to the novel — it was written by an Italian. The film’s going to be the same.”

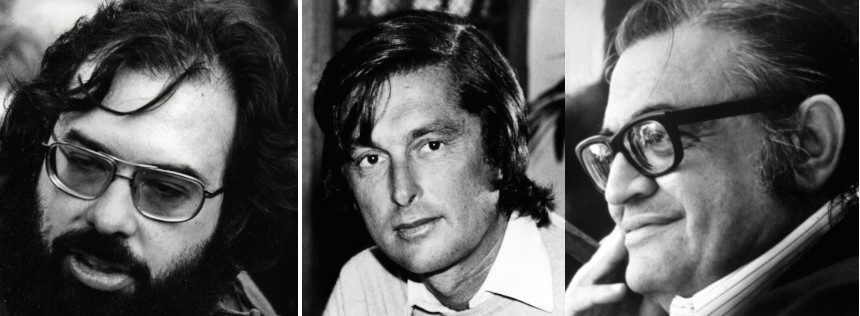

It was Bart who offered up the idea of hiring Francis Ford Coppola. A UCLA film school grad, Coppola made his real breakthrough in the movie business under Roger Corman. Corman was famous for making independent genre fare on extremely small budgets, but was equally revered for his eye for talent. Corman put Coppola to work on just about every facet of production across a series of films; soon Coppola had credits for editing, sound, and associate producer. In 1963, Coppola’s first real directing credit came on a Corman production: Coppola wrote and directed the horror film Dementia-13. The cult success of that film opened more doors for Coppola, and he was soon making critically acclaimed films like You’re a Big Boy Now and Finian’s Rainbow. In 1971, he won an Oscar for co-writing Patton.

Meanwhile, Paramount thought they had found their director, and it was … Sergio Leone. But the Italian filmmaker, revered for his films like The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly, passed to make his own crime picture, Once Upon a Time in America. By the time the studio did get around to asking Coppola, he joined the list of directors who were hesitant to glamorize crime. However, after Coppola hit upon the idea of emphasizing the family behind “the family,” as well as viewing the film through the lens of American capitalism, he decided to take on the film.

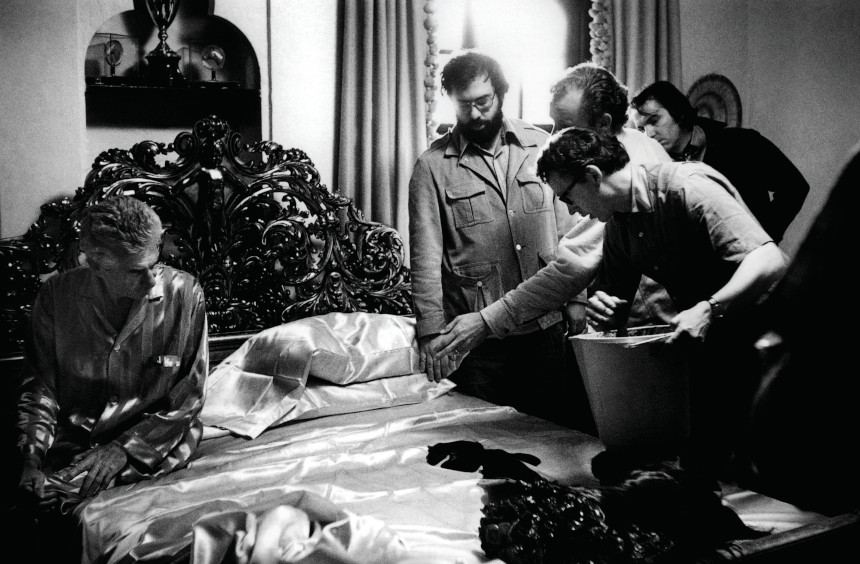

Puzo and Coppola turned into a screenwriting tag team, with each one working on drafts, trading, and incorporating or discarding material from the other. Coppola made a book combining the screenplay and pages ripped from the novel with various notes added. By the time that writer Robert Towne, who went uncredited, pitched in on a third draft, Coppola was leaning more on his compilation book than the actual screenplay. When shooting began, the final draft was still coming together, with Towne making contributions like the dialogue for the scene in the garden where Don Corleone warns his son Michael about a plot to assassinate him.

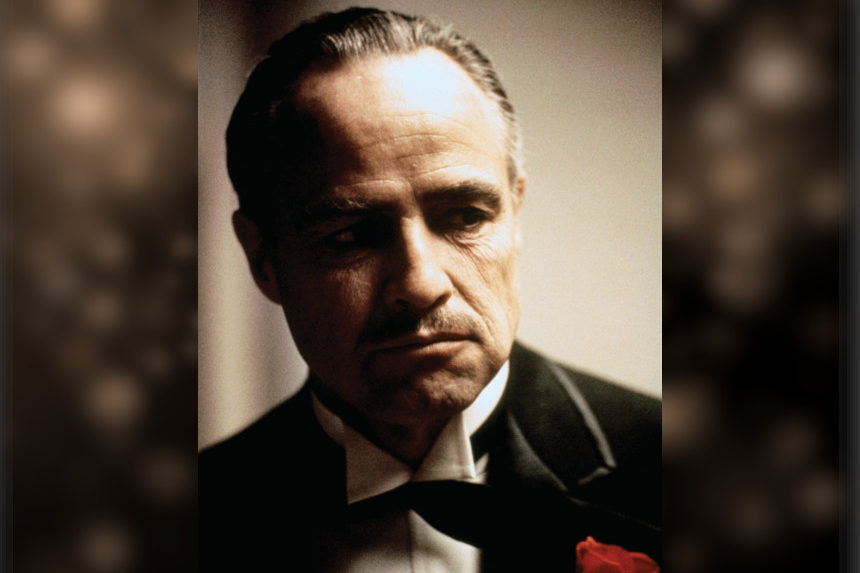

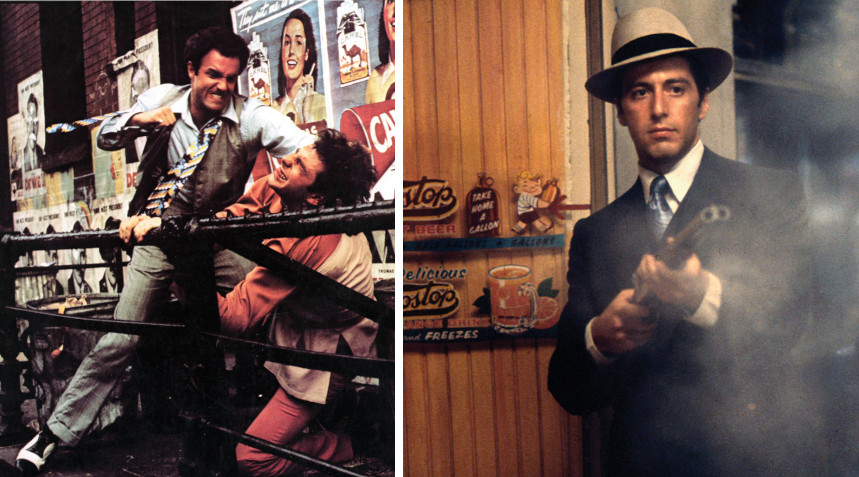

But a screenplay isn’t much good without someone to say the words. While there was initially some tension over the notion of casting notoriously difficult Marlon Brando as Don Corleone, Coppola got the actor he wanted by putting together a silent screen test of the actor, which reassured the studio. More contentious was the role of Michael Corleone. Coppola wanted a little-known actor named Al Pacino, but Evans resisted. Brando weighed in; he wanted Pacino too, appreciating that he was “a brooder,” like him, and could convincingly play his son. Evans finally agreed on the condition that the director cast a favorite of his, James Caan, as Sonny Corleone. “The Family” was coming together, and did so even more appropriately with the addition of Coppola’s own sister, Talia Shire, in the role of Michael and Sonny’s sister, Connie. John Cazale would play the third brother, Fredo, while Robert Duvall would play Tom Hagen, the Don’s consigliere.

Filming ran between March and August of 1971. Coppola leaned primarily on location shooting in New York, California, and Sicily. Constant squabbles with the studio ensued about budget, scheduling, and even the amount of footage that Coppola was shooting per day. Coppola constantly felt like his job was in jeopardy. Evans sided with him after reviewing some of the material that the director had shot, and allowed him to fire both the editor and assistant director over creative differences. After months of editing, a final version was in the can by January 1972.

Much like its source novel, the film The Godfather pulled in multitudes. It was No. 1 at the American box office for 23 straight weeks, easily becoming the biggest moneymaker of 1972. Critics raved, and the film turned into an award-generating behemoth. It was nominated for seven Golden Globes, winning five, and took home three Oscars out of eleven nominations, including Best Picture. That Oscar night also created an opportunity for Brando. Nominated for Best Actor, Brando refused to attend and sent Sacheen Littlefeather, an American Indian rights activist, to accept in his place if he won; Brando did win, and Littlefeather used to time to air grievances about how the film and television industry had represented Native Americans over the decades.

Over the ensuing decades, the reputation of the film has only grown. It’s certain that projects like Goodfellas and The Sopranos would not exist in the same way, or at all, without The Godfather. The sequel, The Godfather: Part II, released in 1974, made a little history of its own. Not only is The Godfather: Part II often seen as one of the rare follow-ups that is equal to or greater than its predecessor, thanks in part to the sterling work of Pacino and Robert DeNiro (as young Vito Corleone), it became the first sequel to win the Best Picture Oscar. In a way, the greatness of the second film helped maintain the reputation of the original.

The influence of The Godfather is so towering that many of today’s critics and filmmakers are simply required to reckon with its legacy. Brandon Peters, host of The Brandon Peters Show on YouTube, noted the importance of the book and film in the development of the modern-day anti-hero. He says, “While the noir era gave us plenty of anti-heroes, Coppola’s film rather reset the table in giving us the ultimate one in Michael Corleone. Pacino’s performance and character was one we got to see become fully formed in his wicked nature. Starting out in the last moments of his innocence, we are witnesses to his fall from grace and embracing a destiny he seemed to have had a pathway to avoid. Michael Corleone was the ultimate blueprint for characters we’d desire in films but also the ones who came to headline some of your biggest, most influential TV shows in The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and currently Ozark.”

Award-winning noir and mystery novelist Alex Segura read the book as a youngster. He says, “Puzo’s pulpy, visceral writing left a permanent impression on me years before I watched the movie. The film, of course, is a classic — regal and thoughtful where Puzo’s novel is gritty and hard-boiled.”

Segura also recognized Coppola’s decision to emphasize the familial connections in the film version. He says, “At its heart, and where it rises above more standard gangster fare, The Godfather trilogy is about family — the lengths people will go to in an effort to protect their loved ones, and the tough choices they will make to keep their secrets and vices safe. It’s quite a feat, even in this era of The Sopranos and Breaking Bad, to get your audience to sympathize with a cold-blooded criminal like Vito Corleone or his sons — but we do, almost immediately, because they’re presented in three dimensions, through the filter of a revolutionary director and thanks to a taut script.”

Peters notes that younger viewers might not realize the cultural impact that the film had in its day. He says, “The film was a phenomenon that would seem unbelievable to today’s audiences. Domestically, adjusted for inflation (and not counting other older films adjusted), [its box office] would only be bested by Star Wars: Episode VII — The Force Awakens.” It runs counter to a lot of the narrative surrounding today’s cinematic successes, Brandon notes, pointing out that, “When cranky film geeks talk about theater-goers of the past being more sophisticated, here’s an example of what fulfills that notion, a rated-R period-set organized crime drama. Nowadays, a name director doing a throwback organized crime drama with more calculated action and violence (The Irishman) went primarily to Netflix, with Oscar recognition but no hardware.”

Coppola did return to the saga a third time 16 years after the second film. Although 1990’s The Godfather: Part III wasn’t held in the same esteem as the first two films, its cultural cachet has grown over time. In 2020, Coppola released a recut version of that movie; titled Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone, the film was warmly, if not wildly, received by critics.

Fifty years on, The Godfather continues to loom large on the cultural landscape. It affected the language. It bred scores of imitators while also showing up-and-coming talent that moments of shocking violence could co-exist with deep drama and artistry. Particular scenes and lines of dialogue are referenced as readily now as they were throughout the ’70s. And of course there’s the praise of legends like Kubrick. This much is clear: Francis Ford Coppola managed to combine Puzo’s story with his own artistry and a stellar cast to make magic. One might say that in the final analysis, Coppola simply made film-goers an offer that they couldn’t refuse.

This article is featured in the March/April 2022 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: AF Archive / Alamy Stock Photo; Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now