When the Pulitzer Prizes were inaugurated in 1917, Frederic G. Melcher found the absence of one category troubling. There were awards for an American novel, play, history book, and biography, but none for children’s literature.

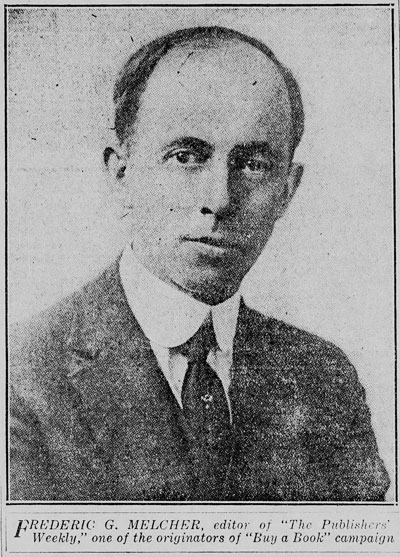

Melcher, a lifelong bookseller and proponent of children’s literacy, sought to fill the gap. In 1921, the 42-year-old coeditor of Publishers Weekly proposed a new prize to the American Library Association. It would become the first award for children’s literature in the world: the Newbery Medal. And on June 27, 1922 — 100 years ago today — the first Newbery was awarded to Hendrik Willem van Loon for The Story of Mankind, a sprawling history of humanity written for kids.

Since then, the Newbery Award has been given yearly to “the author of the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” For each winner of the Newbery Medal, several Honor books are also recognized (called “runners-up” until 1971). This year, the 100th Newbery Medal went to Donna Barba Higuera’s The Last Cuentista, a science fiction tale infused with Mexican folklore.

At Melcher’s suggestion, the award was named for John Newbery, a British publisher and bookshop owner regarded as the “Father of Children’s Literature” for his accomplishments in the business of children’s books. Newbery began publishing books for kids in the mid-1700s and was the first to turn that relatively untapped market into a growing industry.

Melcher, born in 1879, began selling books at age 16 and rose through the ranks, later becoming coeditor of Publishers Weekly, then president of the magazine’s publisher. He devoted much of his career to promoting children’s literature and reading. Two years before proposing the Newbery, he collaborated with Anne Carroll Moore, the Superintendent of Children’s Works at the New York Public Library, and Franklin K. Mathiews, chief librarian of the Boy Scouts, to create Children’s Book Week. It was later adopted by the Children’s Book Council and remains the longest-running literacy initiative in the country.

In 1937, Melcher proposed another award to the ALA. This one was named for 19th-century British illustrator Randolph Caldecott and meant to honor “the artist of the most distinguished American Picture Book for Children published in the United States during the preceding year.” The first Caldecott was awarded in 1938 to Animals of the Bible: A Picture Book, written by Helen Dean Fish and illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop.

The Newbery and Caldecott medals were intended to be essentially noncommercial. Melcher wanted books assessed on merit rather than economic success and ensured this by delegating judgment to those most qualified. Since the awards were created, children’s librarians — people who have direct experience with the books and insight into their effects on kids — have decided the winners, not publishers or sales numbers. The annual decision rests with the ALA’s Association for Library Service to Children division (previously called the Children’s Librarians Section). As historian Leonard S. Marcus told Publishers Weekly, the awards were about “setting high standards for children’s literature. They were intended to help parents know what to buy for their children.” According to Marcus, the Newbery and Caldecott awards have built the canon of American classic children’s books.

If a Newbery or Caldecott winner did happen to be selling poorly before the award, its success would skyrocket afterward. The medals create guaranteed boosts in sales, and awarded books spend long periods of time on The New York Times Best Seller list. The medals can also have a tremendous impact on authors’ careers. In 1964, for example, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are won the Caldecott, giving the author his first taste of national recognition. The book was his 57th.

The annual promotion of the Newbery-winning book is just part of the award’s intended purpose. Medaled and honored children’s literature is more likely to be discussed among readers and often enjoys permanent shelving in libraries. The ALA’s choice of winner stimulates readers to consider what makes a book worthy of such a high honor. Kids can get involved in discussions like these using the ALA’s Mock Newbery Toolkit, which encourages participants to choose their own favorite books and narrow them down to a winner.

The Association for Library Service to Children’s choices of winners have been heavily examined and frequently criticized through the years. Many readers resented the fact that E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web won an honor in 1953 rather than the Newbery Medal itself. It’s widely believed that the book didn’t win because of Charlotte’s death; dying was not discussed in children’s literature at the time. Other choices have been criticized because they mention certain anatomy. These instances serve to remind us of an essential nature of the Newbery Medal: however our standards for children’s literature change in the award’s second century, it will continue to get kids reading, and that was Melcher’s essential goal.

Featured image: Illustration by Norman Rockwell

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now