The original Constitution did not define who qualified as a U.S. citizen. It merely acknowledged that citizenship existed: Article II said the president must be a citizen and Article III mentioned legal dispute between citizens of different states. It also didn’t specify which residents of America had the rights of citizens.

However, Article I, Section 2, determined there would be no government representation for “Indians not taxed,” — a phrase whose exact meaning is now lost, but which might have meant Native Americans living in white communities, off of tribal lands.

Citizenship for members of American Indian tribes wouldn’t have occurred to the founders because these Americans were considered members of foreign nations, each with its own citizens and treaties.

The United States first offered citizenship to Native Americans in the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. In it, the Choctaw tribe exchanged its 11 million acres of tribal land in Mississippi for 15 million acres in Oklahoma and Kansas. The treaty came out of the Indian Removal Act, which relocated Native Americans across the Mississippi River to make room for white settlers.

The Choctaw signed with the provision that American Indian families could remain in the area. Each householder would be allotted 640 acres with an additional 300 for each child under the age of 10. And they could become citizens.

Government negotiators didn’t expect many would remain as they watched 13,000 pack their belongings and head west. But 6,000 never left or else returned from the West. These Choctaw represented the first indiginous citizens of the United States.

In 1857, American Indian citizenship received unexpected support from the Supreme Court. In Dred Scott v. Sandford, Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled that African Americans, though born in America, did not qualify for citizenship. However, Native Americans, descendants of “free and independent people,” could become naturalized citizens of the U.S. like any emigrant.

After the Civil War, the government ensured the rights of Black Americans newly freed from slavery with the Civil Rights Act of 1866. It stated that anyone born in the U.S. was a citizen “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” Anyone, that is, except “Indians not taxed.”

The 14th Amendment of 1868 further clarified the citizenship and rights of Black Americans, declaring all persons “born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” were citizens. But the Senate judiciary committee determined “the 14th Amendment to the Constitution has no effect whatever upon the status of the Indian tribes within the limits of the United States.”

By this time, only eight percent of Native Americans were paying taxes and eligible for citizenship.

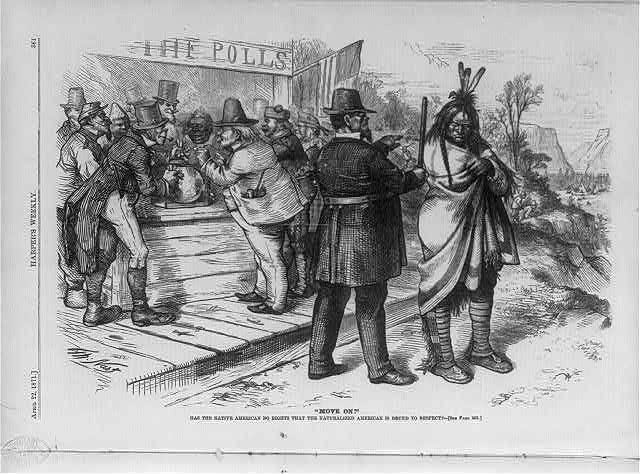

In 1884, the Supreme Court again ventured into the question of Indian citizenship when it decided that those who were taxed didn’t have the right to vote in elections. The case was brought by John Elk, a Native American who had left his tribe, moved off the reservation to Omaha, spoke English, paid taxes, and tried to vote.

The Court said Elk had no claim to citizenship because, even though he was a taxpayer, he’d never been naturalized as an American citizen. And the 14th Amendment didn’t apply because Elk was born as the subject of an alien power: an American Indian nation.

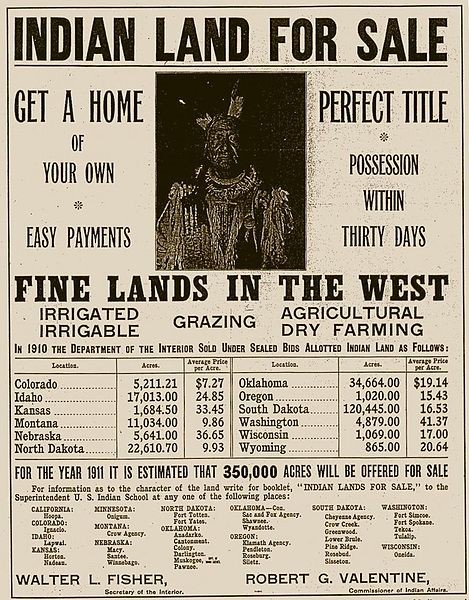

In 1887, Senator Henry Dawes sponsored a bill intended to help Native Americans assimilate into white society. It distributed tribal land among native individuals with the hope that they would take up farming and start moving into mainstream America. This would enable the government to get out of the business of overseeing American Indian welfare.

Each qualified head of a Native American household would receive 160 acres (unmarried members qualified for 80). The recipients then became citizens, subject to federal, state, and local laws, as well as taxes.

The Act proved disastrous. Nomadic Native Americans found farming alien and difficult, and some of the land was unsuitable for farming. Tribal societies fell apart. Poverty, disease, and hopelessness grew in the reservations. Worst of all, the Act permitted any land not allotted to Native Americans to be sold to whites. By the turn of the century, Native Americans had lost almost half their land to white speculators who bought or cheated the land from the tribes. And about 90,000 Native Americans were left without land.

By the early 20th century, American Indians could gain citizenship by only a few avenues: serving in the military, marrying white Americans, accepting land allotments like those given in the Dawes Act, or moving off tribal land, paying taxes, and undergoing naturalization.

Then came the First World War.

All American Indians were ordered to register for military service, though they could choose not to serve if they weren’t citizens. The men in some tribes refused to even register. But many others elected to serve anyway.

Around 6,500 chose to be conscripted. And another 5,000 enlisted because military service was considered an honorable tradition in their tribes.

Overall, 25 percent of American Indians served in World War I. They were among the first U.S. combat units to reach France in 1917, and fought in every critical engagement. They served despite a long history of discrimination against their people and their cultures. And they served, General Pershing said, “with the courage and valor of his ancestors.” This courage often took them into the heaviest fighting, which was why five percent of Native American soldiers were killed, compared to one percent of U.S. forces as a whole.

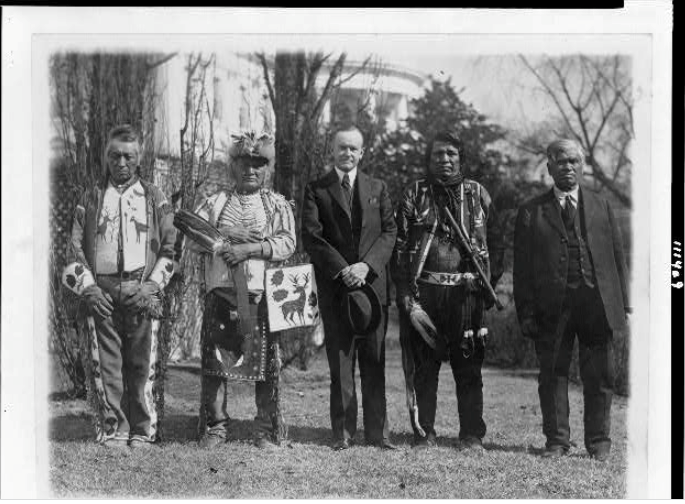

Six years after the war ended, Congress finally recognized the American spirit of its Indian Nations. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 declared “All non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States.” It applied to the half of America’s 300,000 indigenous people who hadn’t gained citizenship by other means.

But American Indians soon learned that citizenship did not come with the right to vote, which was determined by state governments. Fourteen years after the Citizenship Act was passed, seven states still refused voting rights to Native Americans. Between 1948 and 1958, state regulations against their voting in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and North Dakota had been successfully challenged. Not until 1970, when the Supreme Court struck down Oregon’s literacy requirements for voting, could Native Americans fully participate in elections.

But new requirements have made voting difficult on tribal lands. Many Native Americans do not have drivers’ licenses, or photo ID, or a traditional street address. Homes on the reservation may be identified only by a nearby landmark or crossroad. And post office box addresses aren’t accepted for ID in some states. Furthermore, a 27 percent poverty rate among indigenous people means many voters have no permanent residence.

Voter registration may only be possible far across the reservation. (The Navajo nation is larger than the state of West Virginia.) Some states don’t put polling places on tribal land, or have removed them. In 2016 and 2018, members of the Paiute nation in Arizona had to travel 280 miles (one way) to cast their vote. In 2008, the state of Alaska closed the polls in indigenous villages, which meant residents had to travel by plane to vote.

These factors might explain why, despite all that it took to win suffrage, 34 percent of American Indians aren’t registered to vote. And why Native American voter turnout can be ten percent lower than that of white voters.

Featured image: U.S. allotting surveyor and his interpreter making an American citizen of Chief American Horse, Oglala Sioux, c. 1907 (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now