A few hours after the residents of Boise City, Oklahoma, wrapped up their Fourth of July celebrations in 1943, something truly earth-shaking happened in this tiny Panhandle town. Early in the morning of July 5, a U.S. Army Air Corps flight crew leaving the Dalhart, Texas, air base was heading toward a practice bombing range in Conlen, Texas – or so they thought.

The crew’s flight navigator hadn’t worked on a nighttime mission before, according to the local museum. They missed the target by nearly 43 miles, releasing their bombs over Boise City, Oklahoma.

When the bomb-bay doors opened, history was made. But rather than wiping this town off the map, the practice bombing raid gone wrong made Boise City one of the only American towns to be attacked during World War II, and the only town to be accidentally bombed by the U.S. military. Nearly 80 years later, the bombing of Boise City remains the town’s claim to fame – and the story recently had an explosive development.

Night Flight With No Light

The crew knew something was wrong when the lights went out.

In the dry, flat Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles, guiding landmarks are few and far between. At night, they’re useless anyway. Keeping a plane on course can be done only by using a compass, a task that the crew onboard the B-17 apparently struggled with.

Navigator John M. Daly “needed more training,” according to the book Boise City Bombed – Still Booming, by Norma Gene Young, whose family owned The Boise City News. Daly directed the plane north instead of east by accident, locals say. The crew flew north from Dalhart for several miles and finally saw what they thought were the lights of the practice bombing range. In reality, the lights were those of the county courthouse in the downtown square. One by one, they dropped six practice bombs filled mostly with sand, but with enough explosive material to leave a mark.

As bombs fell from the sky, Sheriff Harris “Hook” Powell and resident Hurlie Reed tried to contact the military base, Young wrote. However, they had “nothing but bad luck” until two soldiers, who had been on a picnic with some local women, arrived at the telephone office. The soldiers “knew whom to contact to inform them that the town surrendered,” Young wrote. After the base got the call, the radio operator contacted all nearby military aircraft to alert them that someone was bombing the town, not the range. But the crew above Boise City didn’t think they were the off-target aircraft.

Suddenly, the illuminated area went black. “Only then, after the lights went out, did the crew of the plane decide that maybe they were the guilty guys – and the raid was over,” Young wrote. “Or perhaps they assumed they had made a direct hit on their ‘enemy.’”

The crew returned to Dalhart as the people of Boise City left their homes in a daze, shaken from their slumber by the sounds of repeated explosions. The lights went out not because of damage to the city electrical system, but because a city power plant worker realized what was happening. Frank Garrett, the newspaper reported, pulled the main switch at the plant, shutting down the lights to alert the crew.

The Missing Link

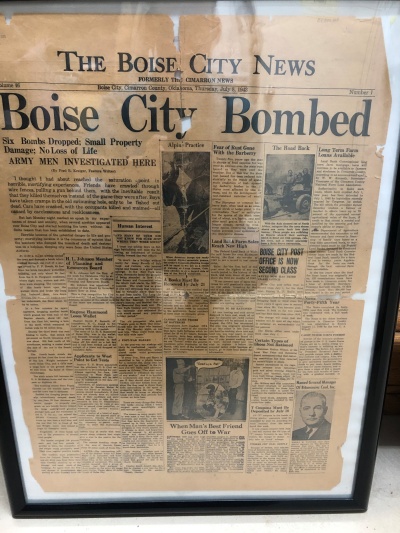

The July 8 edition of the Boise City News carried a banner headline in bold, black type: “BOISE CITY BOMBED.”

In the days after the accidental attack, rumors swirled about the number of planes and bombs involved. Getting the details right took a while, but that didn’t stop the news from spreading and being chronicled across the nation. Meanwhile, some residents worried that the attack was legitimate.

Fred R. Kreiger, a feature writer for the Boise City News, captured the feeling of fear some people had when their town was rattled that morning. “I thought I had about reached the saturation point in horrible, mortifying experiences,” Kreiger wrote in a front-page story. “But last Monday night marked an epoch in my experiences of dread and anxiety, when several airships appeared over Boise City and started bombing the town without definite reason that has been established to date. Horrible because of the potential danger to life and property; mortifying because it is the consensus of opinion that the bombers who dumped the missils [sic] of death and destruction on a helpless, sleeping city were from the United States Airforce [sic].”

In spite of residents’ worst fears, no lives were lost, and no one was injured. But crisis was only narrowly averted. Some bombs fell near occupied homes, while one missed a fuel tanker truck by mere feet. “The driver screeched out of there instantly, and as far as is known, has never returned,” Young wrote.

As townspeople gathered in the downtown square, Mayor C.E. Palmer tried to calm people, explaining that the situation was a mishap and saying “our service men need our support,” according to his speech, transcribed in Young’s book about the bombing. His plea was apparently well-received; people purchased thousands of dollars in war bonds at a table set up at the Baptist church, nearly missed by the attack, Young wrote. Soldiers soon came to Boise City to sort out the mess and collect the bombs. However, they only located the first five. The sixth remained missing.

An Explosive Display

A few weeks after the bombing, railroad worker Jerry Shannon was loading sand in railroad cars near the edge of town. While moving the material, he found a gray, metal object that was dented, but intact, in a pile of sand. It turned out to be the missing bomb, which hadn’t detonated because of its soft landing.

Shannon knew exactly what his discovery was – and that’s why he kept it in his barn until his death in 2019. After his passing, his son decided the bomb needed to go on permanent public display. In May 2022, after receiving a fresh coat of paint, it was given to the town museum, the Cimarron Heritage Center. It hangs outside the museum on a metal stand, angled downward as if it were ready to hit the ground again.

“I’m so glad he gave it to the museum,” says museum director Jodie Risley. “I’m just really proud of that right now.”

The bomb is the latest addition to the museum’s bombing displays, which are among its most popular, Risley says. The museum has newspaper clippings from the era and replica bombs that, until now, gave curious tourists an idea of what the “real deal” looked like. The story has been passed down through the generations, and Risley has hope it will continue, noting there is still a lot of interest.

‘I Wasn’t Afraid’

While some Boise City residents were afraid during and after the bombing, their worries gave way to humor. The town has conducted celebrations commemorating the bombing’s anniversary, and Risley says she’s planning the 80th anniversary for 2023. Residents proudly talk and laugh about the night they were attacked; that crowd includes 99-year-old Ellis Marie Adee Ward, who “survived” the bombing.

“I just remember being asleep at night and hearing something exploding,” Ward, who still resides in Boise City, says. “My sister and I had an apartment in a home on North Main Street, and my sister never did wake up. But I heard this noise, and I wondered what it was. I thought it must be a clear night for us to hear from the bombing range. You know, it was a long ways off. And [my sister] said, ‘I don’t know anything about it.’ Well, sure enough, when we went downtown, we found out we’d been bombed.”

Ward posed with for a portrait with her friend, Norma Gene Young (the Boise City Bombed author), in the crater by the church. The photo was published in newspapers across the United States, and it graces the back cover of Young’s book. These days, Ward chuckles when she tells the story from her perspective. “I wasn’t afraid, because I really didn’t know what was happening,” she says. “I just thought it was something a long ways off.”

The story has a happy ending for all involved – even the flight crew. Though they were reprimanded, they later became successful bombers. They led the 800 planes that made up the Eighth Air Force during the first daylight bombing of Berlin, Germany, less than a year later. Daly, the navigator, earned the Distinguished Flying Cross, among several other awards. The crew earned a favorable place not only in combat history, but in Boise City’s history as well.

The first page of Young’s book bears the photo of the dapper young Daly donning his military uniform. “Dedicated to Our Hero, the late John M. Daly,” the caption reads, “who (although it didn’t start out that way) gave us much pleasure through the years.”

Featured Image: One of the original bombs dropped on Boise City is now on display at the town museum. (Photo by Jordan Green)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Boise City is a nice little town. I look forward to visiting once again to learn more of their history.