Any subscriber to streaming platforms has likely been shown a number of previews this year for the same type of television series: a Hollywood rendering of a complex, real-life crime or tragedy. Watching trailer after dim trailer all year, I kept thinking, Another? Since February, fourteen based-on-true-crime drama series have premiered, and more are on the way.

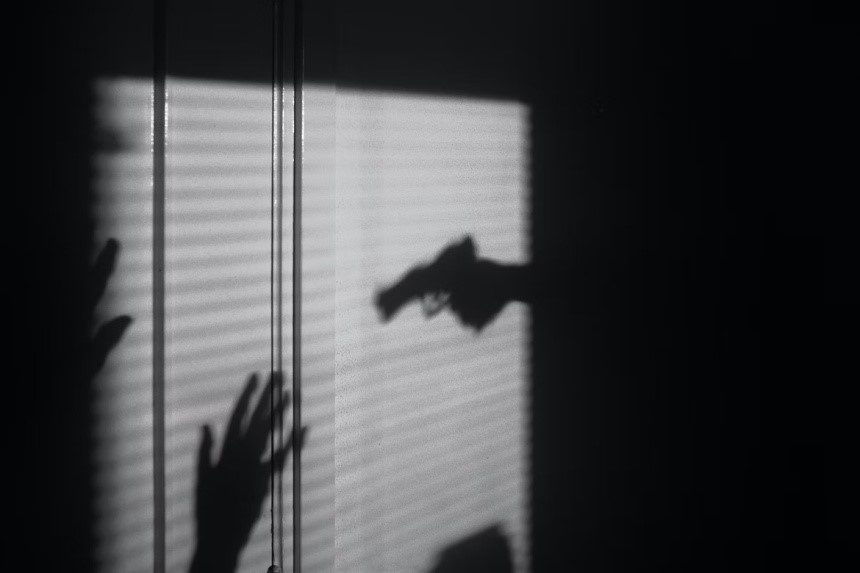

Streaming platforms likely began mass-producing these shows because of the true crime genre’s growing popularity in recent years. That, or an epidemic of writer’s block at the networks is leading to two layers of unoriginality: the repetition of series made in the same format, and the plot of each show, which is, of course, prewritten. The storylines lack the ability to surprise because — spoilers! — the ending has already made newspaper headlines. They retell with gusto stories that have been made into documentaries and written about in books many times over. True stories adapted to entertain are effective because they are by nature believable and thrilling. Viewers know the violence or con artistry they’re seeing has happened in someone else’s real life, so it could happen in theirs.

But are the stories really true? The thing about Hollywood productions that are “based on a true story” is that they reap all the benefits of audience reaction without being bound by, well, the facts. A drama requires narrative, and though real-life crimes provide a structure, they do not provide a script. Everything in between the facts, the moments of emotion that make the show, is conjecture.

When real people are inserted into a television show to be molded into characters, their image has already been decided upon. They are there to fill a hole waiting for a despicable antagonist, loveable hero, or sympathetic victim. Since producers have no obligation to accurately depict the real people these characters are based on, creative freedom allows them to stretch for good drama.

The series Candy, for example, is based on Candy Montgomery, a real woman who was accused of axe-murdering her friend Betty Gore in 1980. Montgomery was exonerated later that year; the court concluded she acted in self-defense. In between those facts, Candy’s producers insert scene after scene of speculation. In the show, Candy’s character gives viewers a distinct feeling that she is capable of murder. In a reenactment of an event nobody witnessed, we see blood splattered on her expressionless face. While depicting Montgomery’s trial, the show places Gore’s ghost in the courtroom, clearly indicating her disappointment that Montgomery is getting away with murder.

Gore is portrayed in the show as a frumpy housewife who mistreats her foster children, and Montgomery as an unnerving and graceful woman. There is no evidence Betty Gore mistreated children in her life, and people who knew her remember her as a sociable, pleasant person. In Candy, Gore’s character is assigned personality traits that make her a convenient dramatic foil to Montgomery’s, and her unpleasantness ultimately contributes by enriching a plot that uses her name, but bends her real-life personality to its own ends.

Whatever theories people have about Montgomery’s guilt — even if they’re correct — a jury ruled in Montgomery’s favor long ago. But the show makes her a villain we can closely observe, and in its continuous, visceral narrative, it creates a story that feels like the “real one,” somehow proving Montgomery’s true guilt in the court of Hulu 40 years later.

Producers don’t leech only from decades-old material like the Montgomery case. Some have used new, still-raw stories to cash in on the true-crime trend. Hulu’s The Girl from Plainville is about Michelle Carter, imprisoned in 2019. Anna Delvey, subject of Netflix’s Inventing Anna, was tried just two years ago. Hulu’s The Dropout was released more than five months before Elizabeth Holmes’s scheduled sentencing date. (They couldn’t even wait for Holmes’s story to “conclude” before putting Amanda Seyfried in her black turtleneck.)

Whether now-fictionalized people deserve the attention the TV dramas bring is less relevant than the uncomfortable fact that many viewers now perceive them based on an actor’s portrayal. What are the consequences of creating dramatized versions of people who are currently walking among us? What damage might be done as a growing viewing public is told “true” stories by series without factual obligations?

Producers do not claim to tell the whole truth in these shows. Still, drama series have the power to take over the narrative of a story, drawing wider audiences than documentaries, books, or articles. This year, more viewers than ever before will learn about real-life cases from fictionalized representations. It matters that many of the subjects still live, are unhappy with networks breathing new life into their traumas, or call out “egregious fabrications” in the show that uses their life for entertainment and profit.

Producers should leave true stories to professionals and go back to original characters. Until then, we as viewers should remain skeptical about the exploitative “truth” of bingeable drama; the weight of factual representation doesn’t belong on its flexible scaffolding.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now