This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

I don’t like being scared, but some of the books I returned to most often and eagerly in a childhood full of reading were those in the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series. This seems to be a relatively common human experience: while most of us prefer to avoid fright as much as possible, we collectively, consistently gravitate to scary stories.

Some of the most famous scary stories feature supernatural villains, sources of fear that are found outside our familiar settings. Yet as terrifying as those threats can be, they don’t hand a candle to the horrors that we humans ourselves can embody. This Halloween, reading some of the foundational American scary stories from a trio of the nation’s early 19th century creative writers — Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe, and Charles Brockden Brown — can help us shiver along with the spookiest sides of society and self alike.

The scary story of Washington Irving’s that has endured most potently in our collective memories across the more than two centuries since its 1819 publication is “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” On the surface, “Legend” seems to present a supernatural horror, as its everyman protagonist, the bookish and meek schoolteacher Ichabod Crane, is terrorized by a mystical local legend known as the Headless Horseman. Yet long before he encounters the Horseman, Crane has a powerful human rival, the wealthy and privileged Brom Bones (“the hero of the country”), against whom Crane is contending for the hand of local beauty Katrina Van Tassel. After the Headless Horseman gets the best of Crane, running him out of town in a genuinely spooky nighttime chase scene, Brom “who, shortly after his rival’s disappearance conducted the blooming Katrina in triumph to the altar, was observed to look exceedingly knowing whenever the story of Ichabod was related, and always burst into a hearty laugh.” The horror in Irving’s scary story is nothing more (and nothing less) than a human bully, one willing to terrorize the weak to get what he wants.

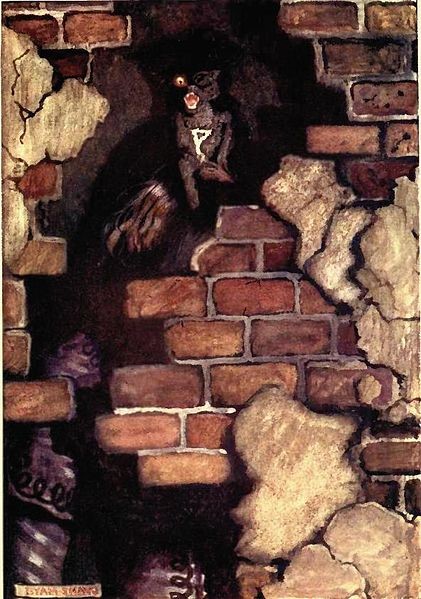

Both the Headless Horseman and Brom Bones are still outside of the main character being terrorized in Irving’s story. But some of the scariest early American stories feature horrors that emerge from inside the protagonists themselves. Edgar Allan Poe, the author most responsible for bringing the global genre of Gothic horror to America, wrote about such internal threats in numerous stories, but never more frighteningly than in “The Black Cat” (1843). Poe’s narrator, a seemingly ordinary man living with his wife and their many pets (including the titular feline), slowly goes mad and commits a series of brutal murders, first of multiple cats and then of his wife. He describes his own dissolution as something somehow out of his control, writing, “In their consequences, these events have terrified — have tortured — have destroyed me.” Yet he is the author of that destruction, not only of his wife but of his own freedom, as “the rabid desire to say something” prompts him to lead the police directly to the spot where he has entombed his murdered wife. In the story’s final sentences the narrator calls the black cat a “hideous beast whose craft had seduced me into murder,” but clearly that phrase better describes his own tortured psyche.

Nearly half a century before Poe published his tale of a descent into murderous madness, Charles Brockden Brown, one of the earliest American novelists, wrote a scary story that linked such terrifying transformations to the United States itself. Brown’s Wieland; or, the Transformation: An American Tale (1798) tells the story of Theodore Wieland, the son of German immigrants and a seemingly successful family man who begins to hear voices that order him to murder his wife and four children. Narrated by Theodore’s impressionable sister Clara, and based in part on a horrific 1781 crime in Tomhannock, New York, Wieland presents various possible reasons for Theodore’s descent, from a family history of madness to religious extremism to a mysterious neighbor. Yet the novel refuses to provide any definitive answers, with Theodore’s eventual suicide leaving Clara and the reader alike forever mystified about the true sources of his murderous rampage.

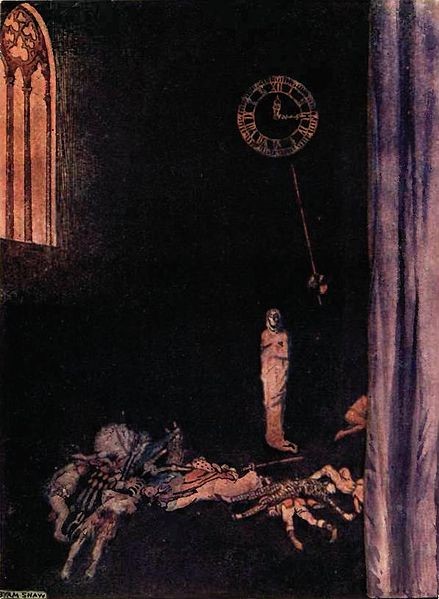

In one of his next novels, Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 (1799), Brown told a fictionalized story of an external terror all too common to that late 18th century period: the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic. As we know all too well in 2022 America, the dangers of epidemics are likewise directly linked to and amplified by human behaviors. Another of Edgar Allan Poe’s scariest stories, “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842), captures those inextricable ties between health crises and human horrors. The titular epidemic is indeed terrifying: “No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous.” But just as horrific is the “voluptuous scene” of the “masked ball of the most unusual magnificence” that the “happy and dauntless” Prince Prospero throws for his wealthy friends while outside that epidemic rages. When the Red Death finds a way to attend Prospero’s ball and destroy him and his friends despite their best efforts to wall themselves off from the suffering of their peers, the destruction feels as ironic and deserved as it does horrific and tragic.

Poe ends “Masque” by writing that “Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.” Hopefully they do not and will not, despite the horrors both external and internal that face us here in late 2022. But Halloween offers an excellent occasion to revisit foundational scary stories that remind us of those horrors, and the all too human shivers they induce.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you for this article. I’ve known about “Wieland” for close to fifty years. If I’m not mistaken, Brockden Brown is considered America’s first professional novelist. In any event, your article makes me want to read it, now.

I thought I knew “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” but it occurs to me from your description of it that I’ve never actually read the story for myself. Bullies. Yes. The most common monsters among us.

I do recommend the Tim Burton – Johnny Depp movie, “Sleepy Hollow.”