Halloween has meant big business in America for a long time. The National Retail Federation estimates that 2022 will see last year’s $10.14 billion spending record broken handily. Those billions are largely spread among three major categories: candy, costumes, and decorations. One fact that’s lost among the gaudy numbers is that even though many consider Halloween a “kid’s holiday,” children don’t have over $10 billion of buying power. It’s just one sign on the road to grasping a larger truth: Halloween was never just for kids.

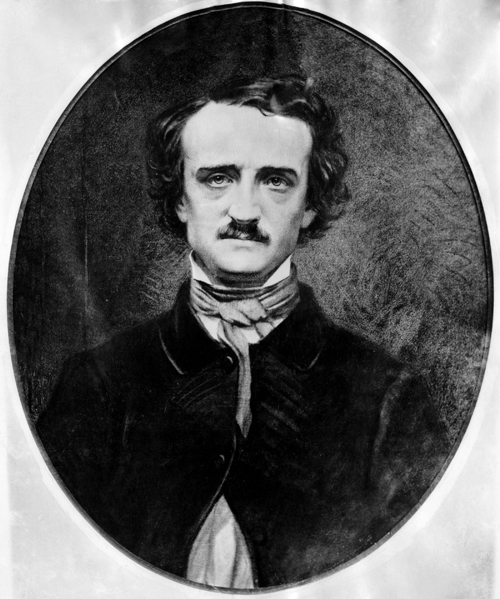

Despite a recent trend of articles that try to tie the uptick in adult Halloween participation to Millennials, it’s just a narrative of convenience. The adult costume party has a cousin in masquerade balls; these affairs go back to at least the 14th century. In her 1979 book, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, Barbara Tuchman details the “Bal des Ardents” (the Ball of the Burning Men), a masquerade that ended in disaster when four revelers were killed after their costumes caught fire. American horror master Edgar Allan Poe based his 1849 story “Hop-Frog” on the incident (which was published seven years after his most well-known masquerade-influenced work, “The Masque of the Red Death”).

There’s also documentation in the 1300s of the mumming tradition, which has often been cited as a forerunner to the practice of trick-or-treating. Mumming also bears a close relationship to guising. Mumming is the short term for Mummers’ plays, which used characters in costumes and masks; the plays generally involve some kind of battle and the resurrection of a deceased character. Guising was a very early form of trick-or-treating, with costumed children going door-to-door for treats like coins or food.

Then there’s Carnival, which grew out of Christian traditions in the Middle Ages. It was the original big party before Lent. By the 1600s, plays and writings acknowledged that believers indulged in face-painting as part of the celebration. Elaborate masks and costumes became a regular part of Carnival season. Our old friend Poe incorporated Carnival into one of his most famous short stories, “The Cask of Amontillado;” in that story, the aggrieved narrator, Montresor, takes revenge on Fortunato, a man dressed as a jester for the party.

Over the centuries, costuming practices found further expression in the popularization of Halloween. Dressing up wasn’t just limited to kids, and it wasn’t limited across social classes. The popularity of donning costumes and trick-or-treating really took root in America after waves of European immigrants arrived in the country in the 1800s. Halloween parades were popular by the end of the century, with Pennsylvania, Kansas, and Indiana newspapers reporting on events that included kids and adults.

Halloween hit a downturn in the early years of the 20th century. World War I had an obvious impact on the tenor of parades and other celebrations, but the real blow was dealt by the 1918 flu pandemic. Halloween activities were expressly cancelled in most major American cities. The pandemic also had recurring waves over the next couple of years through 1921, which continued to cast a pall on celebrations. The end of the decade saw the beginning of the Great Depression, which meant many Americans had no disposible income. Nevertheless, the 1930s saw the emergence of pre-planned haunted attractions (“local haunted houses”) as a more common practice. World War II once again brought widespread rationing and general belt-tightening.

Halloween had regained some equilibrium by 1947, as evinced by “Douglas Goes Begging for Halloween,” a trick-or-treating story in that year’s October issue of Jack and Jill children’s magazine; at that point, trick-or-treat had started to pick back up in new setting: suburbia. The story clearly positions Halloween as a children’s holiday, and one that was sort of an afterthought; the mother in the tale pulls together costumes from stuff that’s just laying around the house.

The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, “Halloween Party” (Season 1, Episode 5) (Uploaded to YouTube by TVintage Classic TV)

Adult costume parties started to pick back up in the 1950s. At least that’s what television would have us think. The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet had a “Halloween Party” episode in 1952, and the massively popular show The Honeymooners devoted two episodes to Halloween parties that involved the adult characters dressing in costume. Halloween episodes of ongoing series would become a TV staple across genres, with action centered on costume parties as perhaps the most frequently recurring theme.

By the 1970s, one event codified the notion that kids and adults could all dress up and have a great time. That was New York’s Village Halloween Parade, which was founded in 1974. Known for its elaborate use of puppetry and its openness to anyone who wants to show up and march, the parade averages 50,000 participants and two million spectators annually. Perhaps not so coincidentally, given the larger traditions in play, it’s often referred to as “New York’s Carnival.”

Over the course of the next two decades, Halloween celebrations were largely expelled from schools for a variety of reasons. The 1980s saw objections to dress-up activities in schools based on everything from the Satanic Panic of the Reagan Era to issues of cultural sensitivity (since many students didn’t celebrate Halloween on religious grounds). Class issues were cited as well, with schools noting that they didn’t want students subjected to peer pressure over the fact that some families couldn’t afford costumes. But even as dressing up was driven out of schools, more and more places appeared to accommodate revelers of all ages. In the ’80s, seasonal pop-up Spirit Halloween and Party City made their debuts, with both chains becoming hubs for adult celebrants.

By 2017, Statista found that 71.7 percent of American adults had some plan to celebrate Halloween, whether it was dressing up and attending parties or simply handing out candy. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, that number plummeted to 58 percent. However, that number has rebounded to 69 percent this year, on par with some of the biggest years tracked. It seems that, public health emergencies aside, Halloween is just as big with adults as ever.

So why the perception of Halloween as a holiday for kids and kids alone? It’s possible that it’s ingrained in the idea of trick-or-treating as a children’s activity, despite the fact that dressing up doesn’t have to be explicitly tied to the gathering of candy. It’s definitely true that certain segments of society frown on adults having any kind of fun, especially if it’s tied to something that people also enjoyed as children (see also cosplay, collecting comics, anime, toy collecting, etc.). But a better question might be, why shouldn’t Halloween be for everyone? If people take joy in dressing up like a favorite character or monster on the one night of the year that it’s expected, why not let them have joy? With centuries of tradition behind it, and other celebrations that support the idea of self-expression through costumes, adults dressing up for Halloween actually seems *gasp* absolutely normal.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now