Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues

⭐️ ⭐️ ⭐️⭐️

Rating: R

Run Time: 1 hour 44 minutes

Stars: Louis Armstrong, Steve Allen, Count Basie, Leonard Bernstein

Director: Sacha Jenkins

Streaming on Apple+

Reviewed at the Toronto International Film Festival

As a kid in the 1960s, to me, Louis Armstrong was that kind of goofy guy who held a handkerchief in one hand, a trumpet in the other, and sang “Hello, Dolly” in a gravelly, almost strangled voice. It wasn’t until after Armstrong died in 1971, and the tributes started pouring in, that it began to dawn on me he’d once been a monumental force in American music.

With this tuneful, touching documentary, director Sacha Jenkins convincingly makes the case that there was no more significant popular music figure in the entire 20th century than Louis Armstrong. In fact, as one of the film’s many musical experts declares, the imitators of Armstrong’s revolutionary invention of “scat” singing — finding unexplored notes between those that had existed on the Western music scale for centuries — included artists from Bing Crosby to the Beatles.

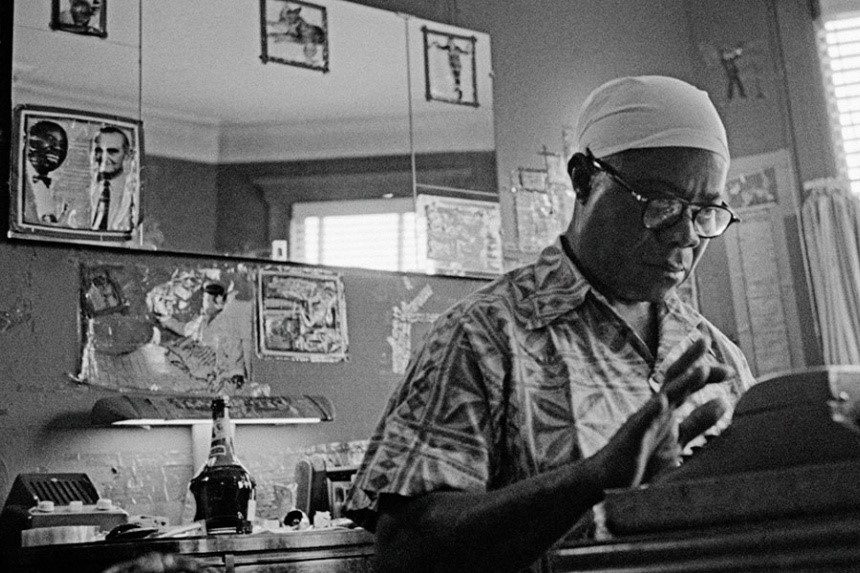

The most compelling narrator of the film, however, is Armstrong himself. In the den of the modest Long Island house that he and his doting wife, Lucille, occupied for the last 30 years of his life, Armstrong recorded hundreds of hours of thoughts and memories. Accessing those tapes, along with a treasure trove of video and movie clips dating back to the 1930s, Jenkins crafts a portrait of a mightily talented, profoundly troubled man whose early struggles to simply survive informed his attitudes toward politics and civil rights for his entire life.

The unfair consensus has always been that Armstrong — a headliner not only in the U.S. but around the world — more or less sat out the civil rights era. As professional peers like Harry Belafonte and Aretha Franklin took center stage demanding equality for African Americans, Armstrong remained conspicuously silent, and this arms-length relationship to the nation’s progressive causes subjected him to lots of resentment and ridicule.

No one was more perturbed by Armstrong’s apparent inaction than the actor Ossie Davis, who time and again put his career on the line in the name of racial equality.

But in a particularly spectacular video find, Jenkins presents a full-length, one-shot monologue by the late actor, telling how his attitude toward Armstrong was forever changed by a chance backstage encounter with the musician — who revealed in heartbreaking detail the scars he bore from the scourge of racism.

That moment alone is worth the price of admission, but there is plenty more to love about this unprecedented look at a man who endured blind hatred, crushing poverty, and bitter misunderstanding — yet who could, at the end of his life, sing with convincing authority, “What a Wonderful World.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

He had ever SEEN! ( I hope it’s this phone. )

Oh, I definitely want to see this. I hope it will soon migrate from Apple+ to something I have.

I’ve heard excerpts from those home tapes. There are probably a lot more of them on YouTube than it’s ever occurred to me to look for.

Great musicians as different from one another as Armstrong and John Lennon have had the instinct to make and keep tapes at home. You don’t say that Armstrong did any riffing on any of them, but by the time he was making tapes at home, he was beyond the need to. One of the most fascinating things I’ve ever heard is a tape of Lennon trying and trying and failing to find the inchoate melody for “Strawberry Fields Forever.” He keeps muttering, “I cannot do it, I cannot do it.”

My veneration of Armstrong is limitless. He was certainly the most important musician America ever produced. His singing should never be appraised as the amusing vanity of a largely talentless singer who was indulged because of his greatness as a horn player ( not that you did ). The excellent popular music and jazz critic and historian, Will Friedwald, considers Armstrong the first great jazz singer.

Ossie Davis once said that he came into a room in which Armstrong had been sitting alone. He hadn’t realized that someone else had come into the room. Davis said that Armstrong unguarded had the saddest countenance he had ever said.