In the days before Norman Rockwell, The Saturday Evening Post searched for the perfect illustrator to become their regular cover artist. Their search led them to a surprising choice.

The cover of the Post was prime space, viewed by millions of Americans every week. It would be a prestigious showcase for any illustrator in the country. The Post’s editor, George Horace Lorimer, studied the dozens of established artists who illustrated the stories inside the Post, but none of them seemed right. After a long search, he selected a young woman — one of the few women illustrators of that era — Sarah Stilwell-Weber.

This is the story of how he chose Stilwell-Weber, and why she turned him down.

Sarah Stilwell was born in Concordville, Pennsylvania in 1878. Few women were able to pursue a career as an artist in those days, but Stilwell loved to draw and was fortunate enough to live down the road from an art school where the famous teacher, Howard Pyle, taught illustration. Pyle saw great promise in Stilwell and admitted her to his class while she was still a teenager. He even arranged for a full scholarship because her father — a harness maker — could not afford to send her.

Stilwell enrolled in 1897, and within a year she had already illustrated her first book: A Children’s Story by Ellen Olney Kirk. Even though she had begun to receive professional assignments, she continued her art classes with Pyle. His classes were rigorous, usually starting at 8:00 a.m. and going through 5:00 or 6:00 p.m. Pyle taught his students that they must dedicate themselves wholly to art, but he was especially demanding of Stilwell and the few other women in his class who aspired to an art career. As recounted in a book about Pyle’s school, The Brandywine Tradition by Henry Pitz, Pyle insisted that any woman who hoped to become an illustrator should give up all thoughts of marriage. He lectured Stilwell that when a woman married “that was the end of her” as an artist. He believed a married woman couldn’t hope to keep up with the deadlines and high standards of illustration.

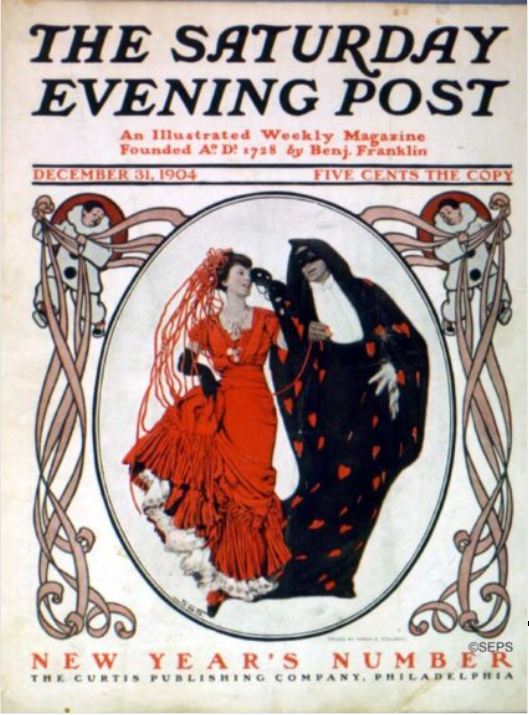

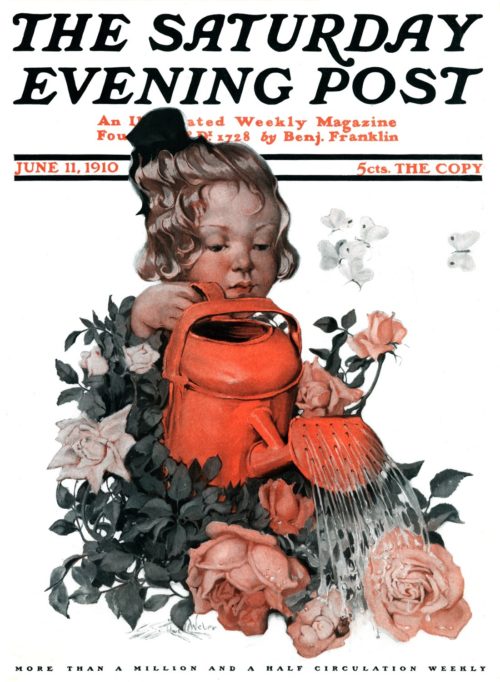

Stilwell finished art school in 1900, but continued to live nearby and consulted her teacher regularly. She was soon commissioned by Century Magazine to illustrate a poem by Josephine Daskin called the “Christmas Hymn of Children.” In 1903 she made halfa-dozen drawings of children at play for St. Nicholas magazine. These pictures solidified her reputation as an artist with a special knack for capturing the magic of childhood, and brought her to the attention of other magazines such as Country Gentleman, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Collier’s, and the Post. In 1904 she illustrated her first cover for the Post.

That same year she illustrated a book entitled Luxury of Children & Some other Luxuries by Edward Sandford Martin. She would soon be called upon to illustrate ads for Kiddie Kar, Rit Dyes, Scranton Lace Company, and Wamsutta Mills. These pictures proved very popular with the public. Despite her shy and modest demeanor, Stilwell had become one of the highest paid illustrators in America.

Post editor Lorimer liked Stilwell’s fresh style, and thought her loving pictures of children would prove popular with the Post’s audience. He approached Stilwell and offered her a contract to paint covers regularly for the Post. This was the opportunity of a lifetime for any illustrator.

But Stilwell turned him down.

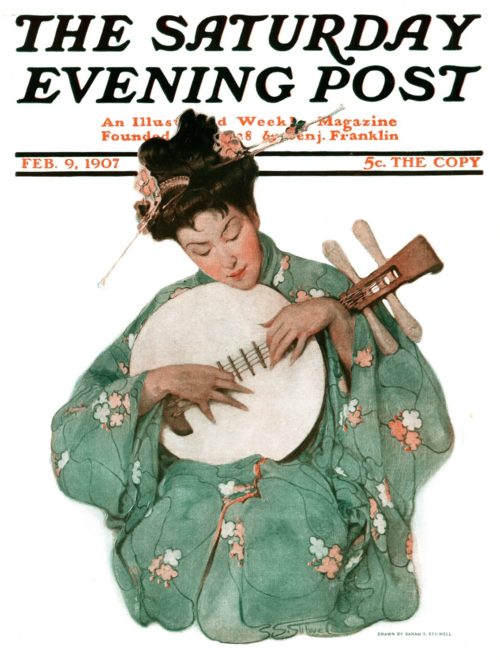

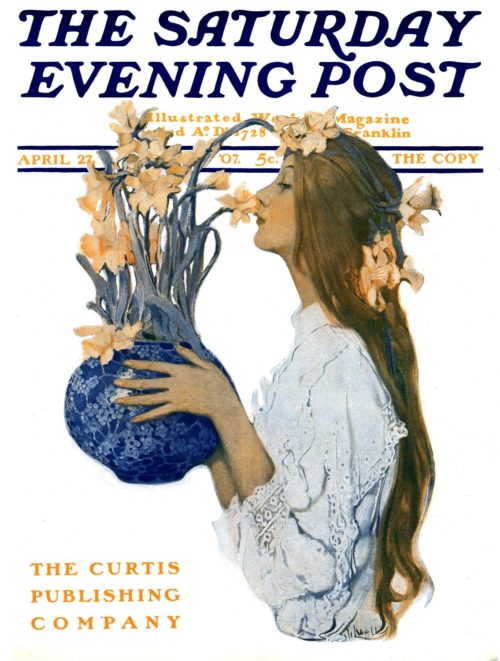

Some said she was not certain she’d be able to deliver high quality covers on a fixed schedule. Others said she had developed other priorities. One thing we do know for certain is that Stilwell dutifully obeyed her mentor’s admonition not to get married until 1907, when she met an English teacher named Herbert S. Weber. The artist’s sister Gertrude later recalled that Weber “wooed her with Chopin nocturnes” and Stilwell was a goner. The couple married in 1909 and later had a daughter named Jane who brought them much joy.

If Stilwell had signed that contract and become the lead cover artist for the Post, Norman Rockwell might never have become the Post’s featured artist. As it was, Stilwell continued to create occasional covers for the Post.

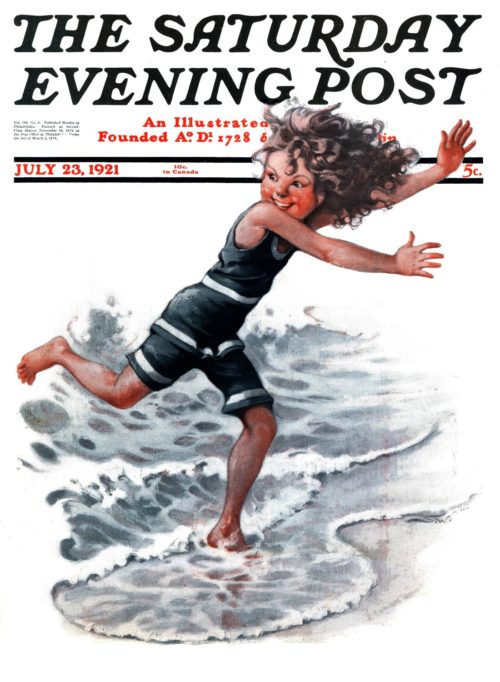

She painted her last cover for the Post in 1921:

Rockwell was hired to paint his first Post cover in 1916, and by 1921 he was firmly ensconced, painting covers on a regular basis.

Stilwell moved to Philadelphia with her family and gradually withdrew from the illustration business. Now named Sarah Stilwell-Weber, she completed one final book, a joint project with her husband called The Musical Tree in 1925. Herbert wrote the story and Stilwell-Weber drew the illustrations.

This year, the Society of Illustrators in New York has elected Stilwell-Weber to its Hall of Fame. There will be an induction ceremony and dinner in November, where the illustrators of today will honor her contribution to the field of illustration, both as an artist and as a pioneering woman who set her own priorities for success.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I take umbrage with the title of this article, a commercial attempt to grab attention that I find distastefully pretentious, unfair to Stilwell, whose name isn’t mentioned in the title, and suggests ignorance on the part of SEP readers. Stilwell was a wonderful artist to be sure, but the article states she was wooed by SEP 12 years ‘before’ artist Norman Rockwell. Therefore to say she nearly ‘replaced’ him is incorrect. You can’t ‘replace’ something that has yet to be, you can only precede it, and to suggest that with Stilwell, Rockwell may never have done SEP covers is baseless conjecture and unfair to Rockwell.

Excellent in-depth feature on Ms. Stilwell, specifically dealing with her nearly becoming the Post’s main cover artist period; not just the Post’s ‘first lady’ of covers. I’m very glad Howard Pyle appreciated her talent, and went the extra mile for her. His demands of Sarah and the few other female students, sound the same as that of his male students; so no claims of special treatment could be claimed later. No. Definitely not.

The publications she’d already done covers for (before the Post) were very impressive. I agree with Lorimer’s reasons for wanting her as the Post’s main illustrator, and had she agreed, no doubt would have fulfilled his expectations. I respect her honesty with him, and to herself in the tough decision to decline the offer. It’s great she did the occasional covers though, with 60 in all. That still puts her as the lead female artist with the most covers (I believe), with Ellen Pyle coming in 2nd with 40.