After decades of living in our homes as part of the furniture, the black vinyl LP had all but vanished by the late ’90s. A few dedicated collectors hoarded them in wooden crates stacked in their basements, occasionally pulling out cardboard Beatles or Marvin Gaye sleeves to remember when music was something to hold carefully in both hands.

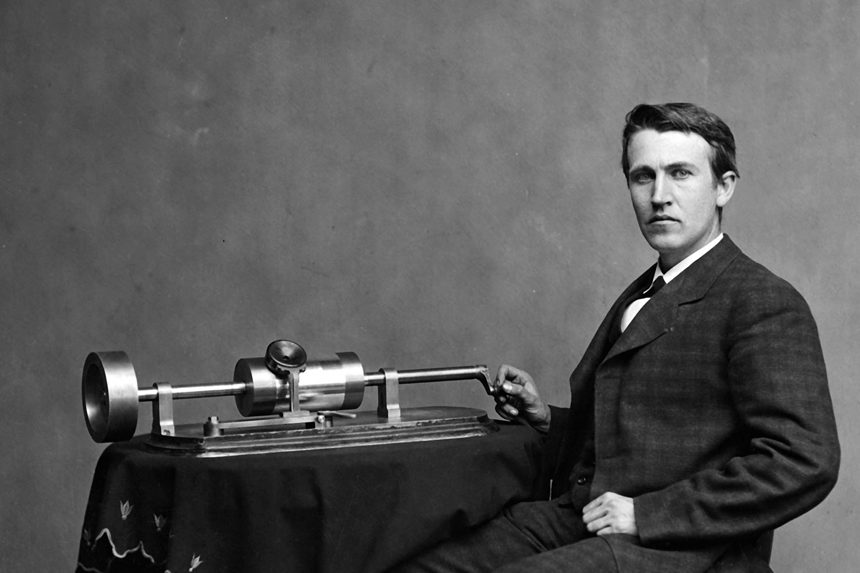

Back then, the record seemed at the end of a 100-year run — a story that began with Thomas Edison, accelerated with the work of a CBS TV and radio executive in the ’40s, and then peaked as sales turned musicians like the Eagles and Michael Jackson into unprecedentedly rich pop stars. Along the way, gramophones and phonographs evolved from wooden Victorian cases topped with awkward metallic horns to the flat boxes of spinning platforms and mechanical tone arms that occupied dorm rooms everywhere.

When I received my first record, The Who’s Meaty Beaty Big and Bouncy, as a bar mitzvah gift from my middle-school friend Scott in 1982, I had no idea Edison had started the phonograph revolution in 1877. And I had never heard of Charles Cros, a French poet who came up with the same idea earlier that same year. Cros had studied the work of 1850s French inventor Léon Scott, who figured out how to imprint sound-wave patterns onto a type of carbon paper. Both Cros and Edison turned this process around, playing the sound vibrations back so people could listen to them over and over.

Edison’s approach, at first, was to imprint those sound waves onto an unwieldly cylinder draped with tinfoil and attached to a screw. His early phonographs were clumsy and difficult to use, but they got the job done — a band could play into 12 recording machines simultaneously, then repeat its song 10 times in a row, laboriously creating 120 wax-cylinder recordings. Even with these limitations, record companies such as Columbia and the New Jersey Phonograph Company began to take advantage by selling John Philip Sousa band productions and Mark Twain spoken-word passages to the public.

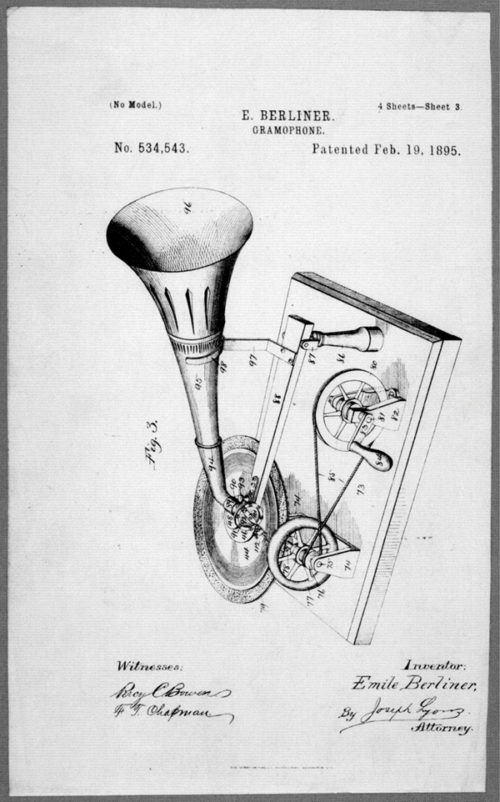

Soon, a German immigrant, Emil Berliner, came to the U.S. and studied Cros’ early papers. Berliner’s innovation was to change the recorded-music format from cylinder to zinc disc. Eventually, he added shellac to the mix and distributed the discs along with a player he called the gramophone. Edison would play catch-up, putting out “diamond discs” of his own through the ’20s, but he abandoned the project to concentrate on radio.

The records took off. In 1914, record companies made 23 million discs, according to Mark Coleman’s book Playback, and over time, musical artists — from vaudeville jazz singer Mamie Smith to crooners Rudy Vallee, Bing Crosby, and Frank Sinatra — became stars as they entered listeners’ living rooms.

The Great Depression briefly destroyed this market, but jukeboxes in the ’30s brought it back through a cheaper 10-inch disc format that played at 78 revolutions per minute, and through sleeker, more compact players such as the $16.50 Duo Jr. turntable.

Peter Goldmark, a Hungarian engineer known for his innovations in color television, had immigrated to the U.S. in the ’30s and taken a job at CBS. He hated records because, as he wrote in his memoir, they provided “the most appalling sounds to emanate out of any machine — tinniness, scratchiness, and clicks — all mingling with the music and adding up to one discordant mess.” After visiting record factories, he came up with a killer idea: CBS would make discs out of a relatively new compound, Vinylite, which was more expensive to produce, but he predicted additional sales would make up for it.

RCA countered Goldmark’s idea with a smaller, cheaper alternative that could hold only four minutes of music on each side — the 45 rpm disc, eventually known to all as “the single.” These formats would dominate music over the next 50 years, with artists from Chuck Berry to Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs putting out singles for jukeboxes and teeny-bopper record players, while LP masterpieces such as Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely in the late ’50s set the stage for the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions.

“The album had the artwork. It had the large dimension, where you could look, touch, feel, and smell everything about the record and the music,” recalls James Caparro, former CEO of Island Def Jam Recordings, who sold vinyl for years in its heyday.

For decades, record companies maintained a massive LP infrastructure — factories, warehouses, trucks, stores. When CDs made LPs obsolete in the late ’80s, many of these disappeared or transformed into something else; when MP3s and online music piracy threatened to destroy the record business in the late ’90s, vinyl extinction seemed certain.

Then a strange thing happened. Beginning in 2007, LPs roared back, selling nearly 1 million copies, according to Nielsen Music, mostly due to college students who liked hanging record sleeves on their dorm-room walls. Last year, sales were 14.3 million. That’s an increase of 1,344 percent. It’s not enough to shift the record business away from Spotify, YouTube, and streaming, but it may just extend the legacies of Emil Berliner, Charles Cros, Peter Goldmark, and, yes, Thomas Edison by a few more years.

This article appears in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really well researched article here. Unfortunately the ‘age of iTunes’ is also (and for many years now) been the crappiest, auto-tuned gimmicked-out garbage of all time Steve, and you can just Google ‘why is today’s music so awful’ and get a lot of good answers. It’s complicated, but validates in spades how I and a lot of people feel.

The love affair with the vinyl records is as much (or much more) about the covers, often beautiful works of art years ago. Many opened up with more beauty inside, or even the occasional poster. Fortunately, a lot of my favorites I bought new by favorite groups that also had amazing covers.

It’s hard to pick a favorite, but if I HAD to, it would be Styx’s ‘Pieces of Eight’ with the hypnotic, Salvidor Dali flavored cover. The Greg Kihn Band has several, the offbeat Flash and the Pan, ELO’s ‘Discovery’, the Car’s ‘Candy-O’ and too many others to mention.

The evolution of music is fascinating. I happen to really appreciate that ‘big-flowered gramophone’ from an early age, and the sound of the early music with tinny imperfections. I watched Dark Shadows with my friends at the time, and composer Robert Cobert composed this song ‘Quentin’s Theme’ that had those attributes. The boy and girl on the show (also 12 in ’69) were interacting with these ghosts from 1897 which had me really interested in that time period otherwise. It also made me interested in music from all the previous decades in the 1900s.

The one from the show is VERY specific. There are other versions on YouTube with the ‘Shadows of the Night’ talking which are terrible, and do not have the real 1890’s haunting beauty of the original. Mind you, this was composed in 1968 by Robert Cobert, a man born in 1924. He composed ALL the music for Dan Curtis; the later Night Stalker, Both Winds of War mini-series, 1991 Dark Shadows.

To find the real thing on the Tube, put in Quentin’s Theme/Original Dark Shadows Audio File and it’ll come up.