This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

With Election Day just around the corner, it’s quite difficult not to feel overwhelmed, and at least a little bit fatigued, by the constant coverage and conversation. The ubiquitous TV ads and all the flyers in our mailboxes. The never-ending stream of imploring emails from candidates and parties and PACs. The social media pictures featuring “I Voted” stickers admonishing us to do the same. Even the voices of pundits and scholars arguing that this is The Most Important Election of Our Lifetime — a perspective with which I agree in this case, but which we’ve heard for at least the last few election cycles.

Filtering out all that noise and focusing on what’s important is no easy task. But at the same time, it is ultimately quite straightforward — no ad or email, no pundit or peer, can go to the polls or mail in a ballot for us. Voting is a personal action, an individual right. And it’s one that is profoundly significant — as illustrated by the long, often painful, always inspiring history of Americans who have struggled, suffered, and sacrificed to extend that right to all of us.

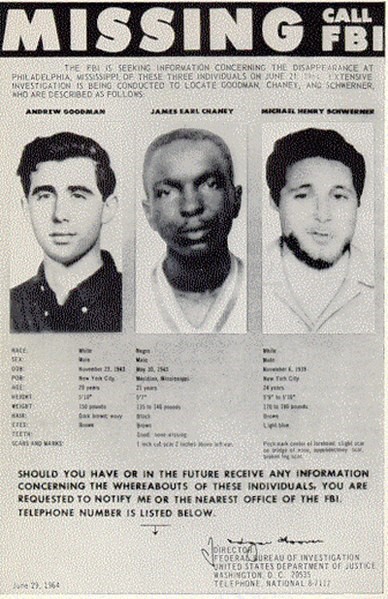

One that is likely most familiar is the June 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The men were in Mississippi working on the Freedom Summer voting rights campaign for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), helping register African Americans to vote across the state. Their murder by Ku Klux Klan members, as I traced in this Considering History column, exemplified more than a century of white supremacist violence and domestic terrorism designed to suppress Black voting rights. But the civil rights movement changed that longstanding trend, and the change came not only because of landmark laws like the 1965 Voting Rights Act, nor only because of prominent protests like the marches in Selma, but also and especially because of the sacrifices of these three young men all those like them who risked violence and death to help register Black voters.

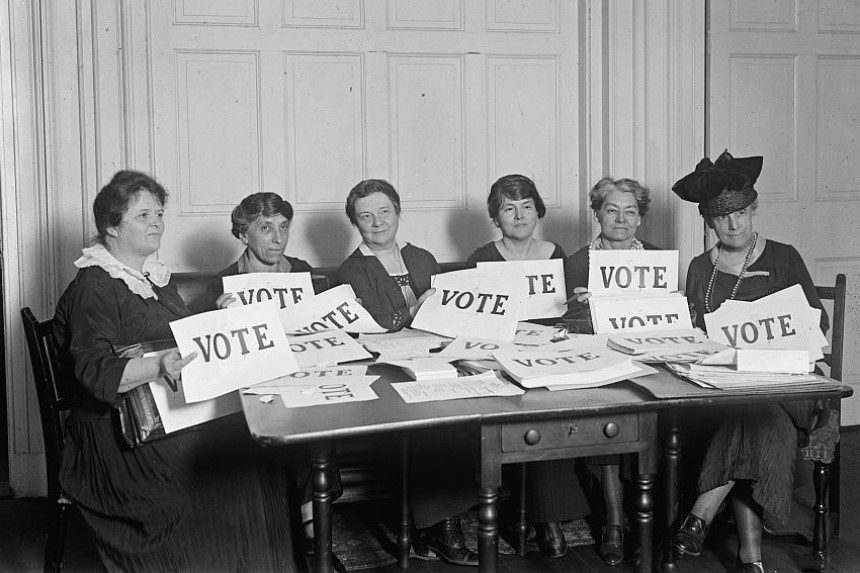

The risks have never been limited to those helping extend voting rights to others, of course—they have also been faced by those fighting for their own rights. Another community who confronted brutal violence in pursuit of the right to vote were the Silent Sentinels, the late 1910s women’s suffrage activists about whom I wrote in this Considering History column. The women who took part in those multi-year Washington, D.C. protests were routinely arrested and frequently brutalized by the authorities, most infamously during the November 1917 “Night of Terror,” which saw more than 40 prison guards in Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse abuse arrested activists for an entire horrific night. But the Silent Sentinels continued their protests for more than two years after that night, embodying the same spirit that led a government physician to note, of suffrage movement leader Alice Paul, “she has a spirit like Joan of Arc, and it is useless to try to change it. She will die but she will never give up.” She and they did not, not until the 19th Amendment granted American women the right to vote.

Just as Alice Paul dedicated her life to securing that right to vote for women, countless other figures have likewise served in the struggle to extend that right to their communities. Mexican American labor and community leader Willie Velásquez became one such dedicated activist in the 1970s. After founding the Mexican American Youth Organization while a college student in the late 1960s and becoming active with both La Raza and the United Farm Workers over the next few years, Velásquez spent the rest of his life helping Latinos secure their right to vote. In 1974 Velásquez established the Southwest Voter Registration Project, an effort driven by the motto Su Voto Es Su Voz (Your Vote Is Your Voice). Barbara Renaud González’s compelling recent biography, Dear San Antonio, I’m Gone but Not Lost (2020), uses Velásquez’s own voice and words to trace all that he sacrificed and achieved in service of that campaign. Velásquez passed away in 1988 at the tragically young age of 44, but his organization and efforts carry on to this day, a legacy celebrated by his posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom (awarded in 1995) and by “El Corrido de Willie Velásquez,” a tribute ballad composed by his brother George Velásquez.

It hasn’t been just leaders and activists who have fought for the right to vote — so too have the countless individual Americans who have stepped up, often in direct challenge to authorities and power structures, to secure and exercise that right. One such inspiring individual was Preston Allen, a Ute Native American living on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in Utah. In 1956, the state’s Attorney General E.R. Callister ruled that “Indians who live on reservations are not entitled to vote in Utah.” Preston Allen, a rancher and World War II veteran, challenged that ruling as a violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments, “suing for himself and other American Indians similarly situated.” Although the Utah Supreme Court ruled against Allen in December 1956, he was not deterred, and his case eventually worked its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. While that decision was still pending in early 1957, the Utah legislature took action, removing Callister’s language from the state codes and granting all Native Americans in the state the right to vote.

In recent years, the North Dakota legislature passed a controversial voter ID law that would have made it impossible for Native Americans living on reservations in the state to vote legally, but that was overturned after legal challenges from Native American activists. The battles fought by Preston Allen and other voting rights activists and leaders are far from over, and the best way we can honor their struggle, sacrifice, and service is to exercise our own right to vote, Tuesday and every chance we get.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now