Recent improvements in the texture and flavor of plant-based meat analogs have meat-lovers as well as vegetarians flocking to buy them. While the quest for mouth-watering faux meat may appear to be a recent trend, it dates back almost a thousand years. According to first-hand written accounts, European religious and political leaders in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance period spent decades searching for meat substitutes.

But Europe’s elite weren’t after mere Tofurkey or Boca Burgers. Their sights were set far beyond Beyond Meat in a hunt for living, breathing, meatless animals.

By and large, the sole nutritional concern during the Middle Ages was how to keep from starving to death. But some of the more privileged had other dietary issues on their minds. One question was whether a sheep that grew on a vine was a vegetable or an animal and if birds that developed inside pods on trees were meatless.

A succession of learned men actually debated such questions, rather than more appropriate ones like “Are we just silly, or completely off the rails?” The idea that one could plant a garden of tree-pod birds and vine-lambs, maybe even a cabbage-patch kid, seemed rational to men who fancied themselves the smartest people in the world.

The origins of the vegetable-lamb tale are a bit woolly, perhaps dating back 2,500 years. The widely traveled Greek historian Herodotus supposedly mentioned it in 442 BCE. But he was 17 at the time, so who knows which exotic plants he observed, and which he smoked. Evidently, a Jewish fable from around 500 CE also references a livestock-on-a-stick translated as “lords of the field.”

From the 14th century through the late 1700s, Europeans made costly expeditions into poorly mapped regions of central and northern Asia to locate this vegetable sheep. Upon return, scholars invariably gushed about the veggie-lamb they almost, but not quite, found.

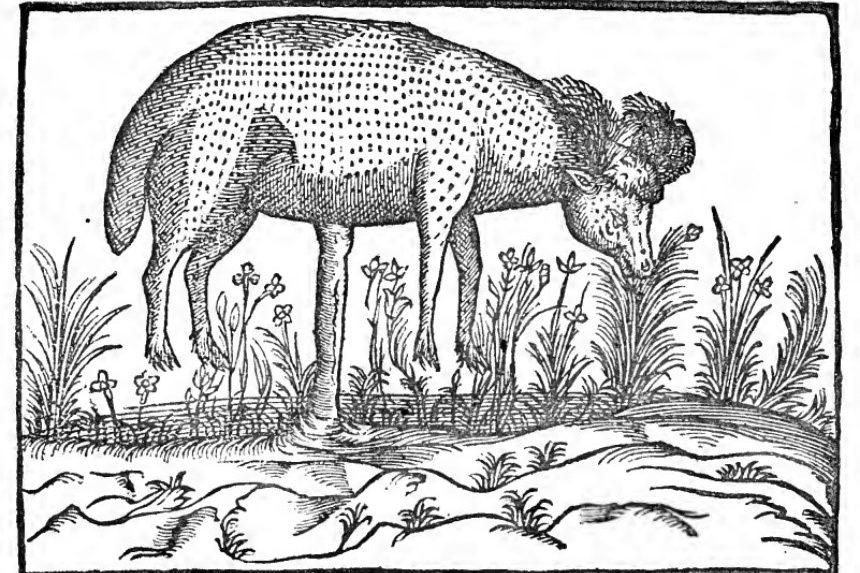

In the 1357 memoir The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Mandeville (a pseudonym) is said to have regaled England’s King Edward III with a description of a gourd-like fruit that one sliced open to reveal a flesh-and-blood lamb that could be eaten as any normal lamb. I wonder if gourd-lambs were seedless or if they were more like watermelons, where you had to spit out sheep-seeds with each bite.

Later explorers described a lamb growing on a vine that connected to its navel like an umbilicus. The critter could graze as far as the umbilicus-tether would allow, but if it broke, the lamb would die. I assume these guys also documented some brainless carnivores in that district, because predators that failed to locate and eat every last vine-bound lamb in their region would have to be pretty inept. Just saying.

“Vegetable lambs” do exist. Native to the Malay Peninsula, Cibotium barometz, the golden woolly fern, has a stout and exceedingly fuzzy surface rhizome which can be roasted, and its starchy insides then eaten. There are no bones or seeds.

Church leaders, bright enough to know fish weren’t plants, nonetheless decided fish were not animals, either. These were the same guys who invented Limbo, the non-Heaven, non-Hell afterlife, so it makes sense in a perverse way that they decreed fish belonged to a special in-between category. Being entirely devoid of “real” muscle tissue, fish were okay to eat on holy days and during Lent, the 40-day period before Easter.

But for the Christians of Europe, eels were an exalted type of aquatic non-animal – eels were beyond fish, you might say. Experts had (wrongly) determined eels lacked those worrisome gonads that tainted all other species with the sin of sex. According to Thomas Aquinas, eating flesh that resulted from sex of any kind might produce “an incentive to lust.” Because they believed that eels did not reproduce in a carnal sense, medieval churchgoers looked upon them as chaste; the perfect asexual, non-meat food for holy days.

Shortly after the Protestant Reformation, the “virgin eel” fad began to lose steam. Then in the 1890s, someone managed to find eels with proper genitals, bursting that bubble forever. But eating “non-animal” fish on fasting days of some Christian denominations continues to this day.

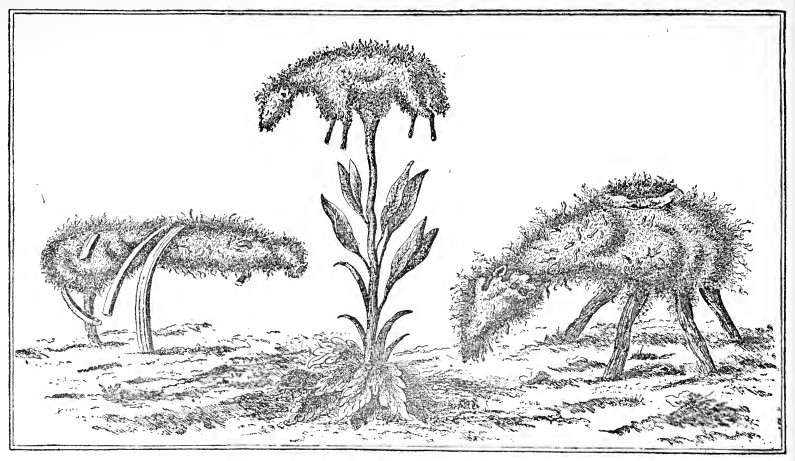

In the 11th century, tree-pod geese were discovered by monastic monks living on remote, barren islands in the northern British Isles. Perhaps they were so malnourished that they hallucinated, because monks would never lie to the Pope. Right? Apparently, this group of monks swore they saw trees with pods that fell into the ocean and became “Bernacae” (barnacle) geese.

They (monks, not geese) sent a letter to Pope Urban II, who agreed with the logic that plant-based geese were just dandy to eat on mandatory fast-days when real animals, whose parents engaged in lewd acts, could not be touched. This went on for well over a hundred years until Pope Innocent III ruled that even though some geese grew on trees, they were off-limits on fasting days. It seems the Pope did not verify that monks on various rocky clifftop monasteries were copied on his memo, as “meatless” goose dinners reportedly went on in some areas into the 20th century.

The real-life barnacle goose, Branta leucopsis, breeds in the Scottish Hebrides as well as on Ireland’s northwest coast, in Greenland, and some other North Atlantic locations. They’re quite secretive, often nesting in high cliffs. As a result, fledged juveniles “come out of nowhere” when they first tumble into the water.

Given the pace of research into meat substitutes, we may well have a vegetable lamb or goose one day. For some parents, it might be the only way to get the kids to eat vegetables.

Paul Hetzler prefers meatless vegetables and seedless lamb.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now