You probably know him as the man with shortest presidency — 31 days. But William Henry Harrison deserves to be remembered for more than that.

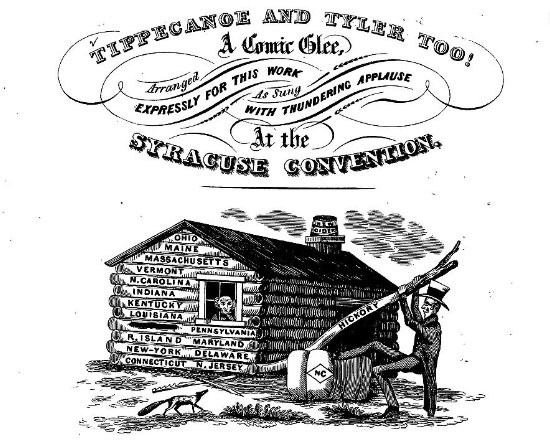

For one thing, he was the first person to run what could be considered a modern presidential campaign, which created a persona for the candidate — in Harrison’s case, that of a crude backwoodsman. The image arose from a journalist’s criticism in the run up to the 1840 election: “Give him a barrel of hard cider and settle a pension of 2,000 a year on him and he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin.”

Harrison’s campaign never bothered to dispute this fairly inaccurate image of him. They could have argued that he had attended college and gone on to medical school, and that he came from a well-established family, grew up on a plantation with over 100 slaves, and now owned over 2,000 acres.

Instead, his campaign directors in the Whig party promoted the connection between log cabins and the candidate. They said it proved that Harrison was a “true” American, a man of the people who lived a simple life on the frontier.

Many citizens in 1840 had been born in cabins. They had since moved on to live in comfortable houses, but to them, log cabins were essentially American. And so, consequently, was Harrison. He was the opposite of incumbent president Martin Van Buren, who had a reputation of living in luxury in the White House.

Harrison had the further appeal of being a war hero. He had fought and defeated Shawnee Indians beside the Tippecanoe River, which earned him the nickname “Tippecanoe.” When he was paired with vice presidential candidate John Tyler, a campaign slogan suggested itself: “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.”

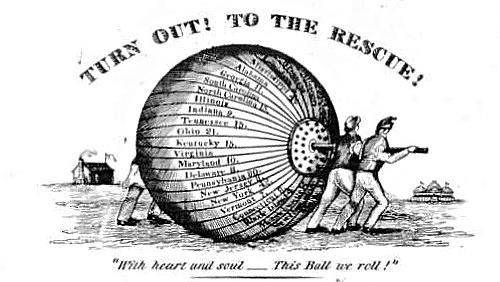

The Harrison campaign also used the slogan, “Log Cabins and Hard Cider,” and it organized parades with floats that carried log cabins. Teams of backers also promoted Harrison’s candidacy by rolling a giant ball with pro-Harrison slogans through towns and across country.

They wore coonskin caps and carried jugs of hard cider, which they offered to any potential supporter. They handed out log cabin soap, handkerchiefs with Harrison’s image, and miniature log-cabin shaped bottles of “Old Cabin Whiskey” from the E. G. Booz Distillery of Philadelphia.

Another way that Harrison departed from tradition was by campaigning for himself. Previously, candidates had avoided making public appearances, choosing to remain aloof from politicking. But Harrison regularly appeared at rallies, which drew audiences of up to 50,000 people.

And where did Harrison stand on the important issues of the day? No one was certain. He spoke in patriotic generalities but remained noncommittal on key issues, trying to antagonize as few voters as possible. In his speeches, he appealed to voters’ emotions, not their reason. As a Harrison campaign worker said, “passion and prejudice, properly aroused and directed, would do about as well as principle and reason in a party contest.”

The Democratic party was stunned by the energy and organization of the Whig campaign — and by the enthusiasm Harrison stirred among voters in the 1840 election. Four years earlier, in 1836, 56 percent of voters had cast ballots. But in 1840, 80 percent of voters participated, the second highest turnout in American history, exceeded only by the 81 percent in the 1860 election.

Harrison could laugh off the accusation that he was a rough, uneducated rustic. But he was stung by comments about his age. At 64, he was the oldest candidate ever elected. One critic had dismissed him as feeble and senile, calling him a “superannuated and pitiable dotard.”

Harrison set out to prove the criticism wrong. To demonstrate his fortitude, he and his retinue marched up Pennsylvania Avenue to his inauguration on a cold day on March 4th, instead of riding in carriages as all other presidents-elect had done.

After he had been sworn in, Harrison had an opportunity to prove that his mental powers were not affected by age: He would deliver an inaugural address that would show off his classical education.

The first sentence alone — 100 words long — should have been a warning to the audience that the speaker would be verbose.

Called from a retirement which I had supposed was to continue for the residue of my life to fill the chief executive office of this great and free nation, I appear before you, fellow-citizens, to take the oaths which the Constitution prescribes as a necessary qualification for the performance of its duties; and in obedience to a custom coeval with our Government and what I believe to be your expectations I proceed to present to you a summary of the principles which will govern me in the discharge of the duties which I shall be called upon to perform.

His didn’t stop talking for another two hours, setting a record for inaugural speeches that hasn’t yet been broken.

Harrison came down with a cold soon after the inauguration. It didn’t kill him, but it left him weakened. In the coming weeks, Harrison was often seen around Washington, walking to stores and doing his own shopping. He was determined to show that age hadn’t slowed him.

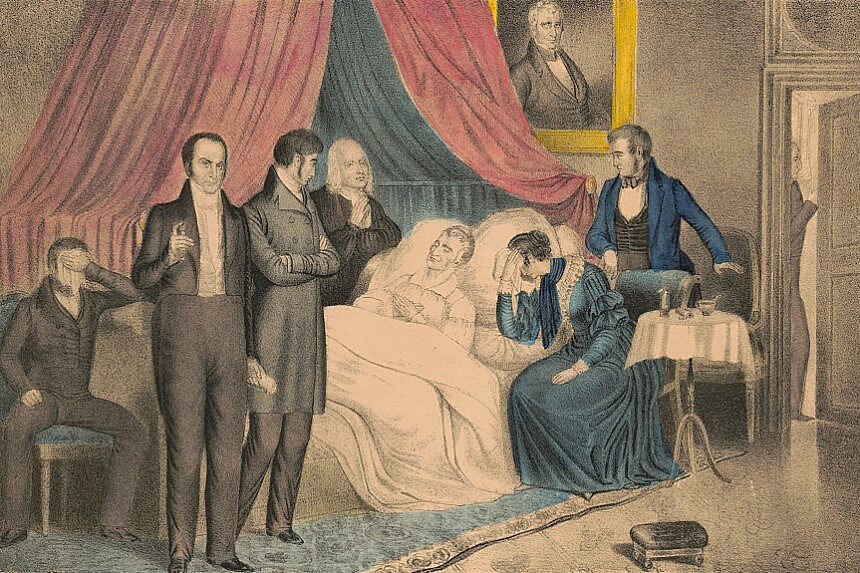

But he was not in good health and was being worn down by office-seekers who besieged him day and night requesting government jobs. He developed another cold, which could have left him susceptible to typhoid from the White House’s contaminated drinking water. He died on April 4th, just 31 days after his inauguration.

In his brief tenure, William Henry Harrison racked up quite a few superlatives: He had the shortest stay in office, gave the longest inauguration speech, was the oldest president of that era, and drove the largest voter turnout up to then. But he should also be remembered as the first president elected with a modern “image” campaign, the first to campaign in person, the first to walk to his inauguration, and the first to die in office. All in a remarkably short time.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now