This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On June 28, 1973, the Black Sports Hall of Fame was created by Black Sports magazine founder and editor Allan P. Barron. Barron argued in an interview with the St. Petersburg Times earlier that year that “Sports is the primary facility Black people have been able to use to overcome obstacles, to break out of the losing syndrome into a winning light, to do the kind of thing this society promises any man can do — go from rags to riches.” The Hall’s 38 initial inductees exemplified such historic achievements across a range of sports as well as eras, from pioneers like Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, and Fritz Pollard to more recent greats like Bill Russell and Muhammad Ali.

Two of those 38 inductees were an interconnected pair of athletes from the world of tennis: legendary champion Althea Gibson and her longtime mentor, coach, and mixed doubles partner Walter Johnson. Gibson and Johnson reflect not only Barron’s point about exemplary individual Black athletes, but also the vital role that the Black community has played in advancing American tennis and sports. With this year’s Wimbledon about to commence, here are five African American legends who together helped shape that inspiring story.

1. Ora Washington (1899-1971)

With all due respect to Babe Ruth, no American athlete dominated the sports world in the 1920s and ’30s more than Ora Washington. The child of Virginia sharecroppers who moved their large family to Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood during the Great Migration, Washington became a force on the African American tennis circuit in the 1920s, winning 12 straight national doubles tournaments with her partner Lula Ballard from 1925-1936 and eight national singles titles between 1929 and 1937. Denied the chance to play in segregated U.S. Tennis Association events, Washington began playing professional basketball as well in 1930, and beginning in 1932 won 11 straight Women’s Colored Basketball World Championships with the Philadelphia Tribune Girls. An inductee in both the Tennis and Basketball Halls of Fame, Washington’s nickname “Queen of Two Courts” was thoroughly deserved.

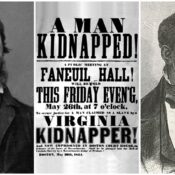

2. Richard Hudlin (1898-1976)

Segregation and racism denied Washington the chance to maximize her athletic achievements, frustrating realities that her contemporary Richard Hudlin would help change. Hudlin was a talented and pioneering tennis player in his own right, playing for the University of Chicago from 1926-28 and becoming the first Black player to captain a Big Ten team in his final year. When he returned to his hometown of St. Louis to coach and mentor young tennis players at his alma mater, Sumner High School, he became an activist as well, filing a 1945 lawsuit against the city’s Muny Tennis Association and its policy of prohibiting Black players from using public tennis courts. His victory in that lawsuit not only encouraged the city’s young Black players, but also led future greats like Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe to come to St. Louis to learn from Hudlin at Sumner High and on those integrated courts.

3. Walter Johnson (1899-1971)

Even more influential in those legendary careers was Robert Walter “Whirlwind” Johnson, the college football star and longtime football coach who became best known as the “Godfather of Black Tennis.” Johnson’s transition from football to tennis was particularly striking and impressive: after he retired from coaching, he graduated from medical school and became Lynchburg, Virginia’s first Black doctor. Believing that tennis would provide the city’s Black community with an important opportunity for exercise, he built a clay court in his own backyard and went on to found the American Tennis Association’s Junior Development Program for young players. His greatest success stories were Althea Gibson, with whom he also partnered to win multiple mixed-doubles titles between 1948 and 1954; and Arthur Ashe, whom Johnson first met and mentored as a ten-year-old in nearby Richmond, Virginia.

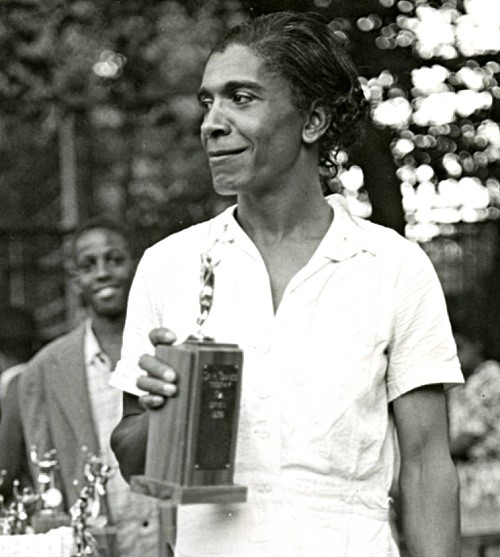

4. Althea Gibson (1927-2003)

Figures like Hudlin and Johnson helped integrate tennis and create more opportunities for players like Althea Gibson (whom they both coached early in her career), but Gibson’s stunning achievements were very much her own. In the three-year period between 1956 and 1958, Gibson won 56 tennis tournaments, including 11 Grand Slam titles: five singles titles, five doubles titles, and a mixed-doubles title; she was the first Black player to win a Grand Slam (the 1956 French Open) and the first to earn the world’s #1 ranking. After that historic run Gibson retired from tennis, frustrated in particular by the small prizes and lack of endorsement opportunities. “Being the Queen of Tennis is all well and good,” she would later write, “but you can’t eat a crown.” Over the next few years she would become the first Black woman on the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour, release the album Althea Gibson Sings (1959), and publish her first memoir, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody (1960). No American athlete has dominated a cultural moment more than Gibson did in the 1950s and ’60s.

5. Arthur Ashe (1943-1993)

While Gibson was at the height of that athletic and cultural prominence, the next great American tennis player, Arthur Ashe, was a teenager, training with Walter Johnson in Virginia and then moving to St. Louis to attend Sumner High School and work with Richard Hudlin. The Black community’s influences on Ashe’s career extended further as well: he was first introduced to the sport by his single father, Arthur Ashe Sr., who worked as the caretaker for the Richmond recreation department; and first mentored by Ron Charity, a talented player and instructor at Virginia Union University, one of the nation’s oldest Black colleges. While attending UCLA on a tennis scholarship and serving for two-and-a-half years in the Army, Ashe became one of the most dominant American tennis players in the sport’s history, winning 76 singles titles (including three Grand Slams) between 1961 and 1978 and becoming the world’s #1 in 1975. He was also a consistent civil rights activist and a humanitarian, even in the face of tragedy: when he contracted HIV from a blood transfusion, he founded the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS; and just two months before his death he founded the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health.

As these athletes illustrate so profoundly, Black sports stories also reveal broader and even more inspiring American histories. The world of tennis, like the Black Sports Hall of Fame, is full of these stories, which can continue to inspire us today.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now