This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the lead-up to the Tokyo Summer Olympics, U.S. track and field star Gwen Berry found herself at the center of another controversy around an athlete’s anthem protest. Berry’s decision to turn away from the flag during a medal ceremony at the U.S. Olympic Trials was not the first time she had used her podium (literally and figuratively) to engage with injustices and inequalities. But because this was the highest-profile such moment yet, Berry’s protest elicited the same criticisms and condemnations that other recent athlete activists such as Colin Kaepernick have experienced, this time amplified by the idea that as an Olympian she is “representing the United States” and should do so only by demonstrating celebratory patriotic actions.

The International Olympic Committee seems to have endorsed that simplistic perspective of what Olympians can and cannot stand for, reinforcing a prohibition that bans demonstrations on the medal stand and allows national sports federations to punish any athletes who undertake them (although the IOC rule does not oppose on-field actions such as kneeling before the start of an event). In response, Berry and more than 150 others have signed onto a letter urging the IOC to reverse this policy and instead prohibit such punishments. The signatories include Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the U.S. track and field athletes whose 1968 Mexico City anthem protest remains the single most famous moment of such Olympic activism and who faced extreme, career-long backlashes as a result (as did Peter Norman, the Australian sprinter who supported them).

Debates over athlete protests and activism can help us expand our definition of patriotism, a vital process for which I’ve made the case in multiple columns here. But such debates can also distract us from a more fundamental reality: that all African American athletes, even those who seem supported by all fans, face racism that limits and all too often defines their careers. The frustrating and tragic case of Jesse Owens potently illustrates that point.

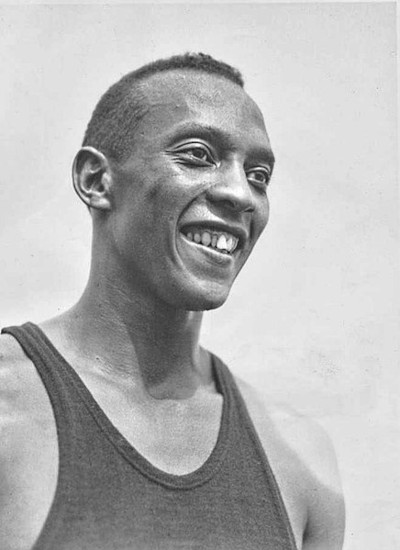

Thanks to a stunning series of performances on the world’s biggest stage in a telling historical moment, Jesse Owens seemed to become a unifying national icon. Only 22 years old and competing in his first international event, Owens took the August 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics by storm, with his four track and field gold medals making him that year’s most awarded athlete. Moreover, because Owens achieved his spectacular success in Nazi Germany, directly challenging Chancellor (or, as he was already calling himself, Führer) Adolf Hitler’s theories of Aryan supremacy, his story (along with that of fellow African American track and field star Mack Robinson) embodied U.S. resistance to the regime and foreshadowed American celebratory patriotic narratives throughout World War II.

Berlin wasn’t the first such superlative athletic triumph for Owens. Just over a year earlier, on May 25, 1935, Owens had the single greatest day in the history of college athletics (and quite possibly sports at any level), setting three world records and tying another within a 45-minute span at the Big Ten Track and Field Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Yet he did so while facing — as he would throughout his record-breaking collegiate career at Ohio State University — systemic racial prejudice, both from society (such as being forced to room and eat at separate, “blacks-only” establishments whenever the team traveled) and from his own institution and team (he was forced to live off campus and was denied the chance at an athletic scholarship, despite being without question one of the greatest college athletes of all time).

One would think that such frustrating realities and limitations would have changed for Owens when he returned from his stirring and symbolic triumphs in Berlin, but they very much did not. President Franklin Roosevelt famously did not invite Owens to the White House, nor did he offer Owens public congratulations of any kind. As Owens himself put it, contrasting false claims that Hitler had refused to shake his hand with this frustrating experience back home, “Hitler didn’t snub me—it was Roosevelt who snubbed me. The President didn’t even send me a telegram.” He would later add, “Some people say Hitler snubbed me. But I tell you, Hitler did not snub me. I am not knocking the President. Remember, I am not a politician, but remember that the President did not send me a message of congratulations because, people said, he was too busy.”

Far more damaging than the President’s snub were the effects of Owens’ continued experiences of racial prejudice and segregation. Again, he had never received an athletic scholarship nor financial support of any kind despite extreme economic hardship, and of course his Olympic successes brought with them no financial reward. So in order to survive, Owens accepted the few endorsements that came his way; as he put it, “What was I supposed to do? I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.” The United States Olympic Committee immediately withdrew his amateur status and banned him from all amateur competition, prematurely ending his collegiate career in the process. By the end of 1936, just four months after his Olympic triumphs, Owens would have to take work as a gas station attendant and playground janitor, all while performing in stunt races against amateurs and even horses, in order to make ends meet.

Owens’ life and story didn’t end there, however. In 1942 he took a job as a personnel director for Ford Motor Company, aided by his collegiate competitor (from the University of Michigan) and fellow ground-breaking African American athlete Willis Ward. In 1946 Owens would use that position to support his fellow athletes of color, helping launch the short-lived West Coast Negro Baseball League for which he served as league vice president and as the owner of the Portland Rosebuds franchise. And while he initially opposed Smith and Carlos’ 1968 Olympic protest, he eventually came around to their position on athlete activism, writing in his 1972 book I Have Changed, “I realized now that militancy in the best sense of the word was the only answer where the black man was concerned, that any black man who wasn’t a militant in 1970 was either blind or a coward.”

The Olympics and sports worlds have changed a great deal since 1968, and even more since 1936. But the unique challenges and pressures faced by African American athletes remain a consistent thread, as we’ve seen clearly through the backlash and vitriol directed at Gwen Berry after her anthem protest. Today in Tokyo, as in Mexico City and Berlin, Black Olympians face overt and subtle prejudices that demand activism and action, from not just those exemplary athletes but all of us.

Featured image: Illustration of Jesse Owens by Robert Charles Howe (©SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now