This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the Trump administration’s 1776 Commission released their report, a self-described “definitive chronicle of the American founding.” Like the commission overall, the report was intended as an overt rebuttal to the New York Times’s 1619 Project, as illustrated by the opening section on slavery and the founding of America: “The most common charge levelled against the founders, and hence against our country itself, is that they were hypocrites who didn’t believe in their stated principles, and therefore the country they built rests on a lie. This charge is untrue, and has done enormous damage, especially in recent years, with a devastating effect on our civic unity and social fabric.”

These two historical projects focus on but also move beyond the specific subject of America’s Revolutionary founding. The 1619 Project seeks to redefine the nation’s origin point from 1776 to 1619, but also to trace the legacy of slavery and racism across every stage of American history. And while the 1776 Commission seeks to respond to that redefinition with a renewed emphasis on the greatness of America’s founders and ideals, it also ignores the role of marginalized groups such as African Americans, Native Americans, and women, and rejects the prevailing historical scholarship. The report has been condemned by history scholars and associations. The American Historical Association wrote: “Written hastily in one month after two desultory and tendentious ‘hearings,’ without any consultation with professional historians of the United States, the report fails to engage a rich and vibrant body of scholarship that has evolved over the last seven decades.”

One of President Biden’s first actions was to disband the 1776 Commission, and its report is no longer available on the White House website. But while that propagandistic effort deserves to disappear, the broader debate over how we remember and understand the American Revolution and founding should continue. And while the report badly misrepresented both the impressive 1619 Project and the fraught, intertwined histories of slavery and the Revolution, it’s also the case that an overtly critical perspective on the founding risks missing a crucial fact: some of the period’s most inspiring patriotic figures and voices were those of enslaved African Americans.

The 1619 Project’s portrayal of the founders and their consistently fraught relationship to slavery is certainly more accurate than was the 1776 Commission’s attempted whitewashing. As I wrote in this Considering History column, George Washington spent a significant portion of his presidency devising methods to deny legal freedom to his slaves, and used his power to relentlessly pursue one escaped enslaved woman, Ona Judge. And as I wrote in this column, Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence included a paragraph that did criticize the practice of slavery but also both blamed it on the King of England and described potential slave rebellions as directly opposed to the Revolution’s goals.

But in using those and other historical details to make the case for the American Revolution as profoundly tied to, and thus the United States overtly founded upon, the horrors of slavery, the 1619 Project also reinforces collective narratives that define the founders as solely or centrally these elite, slave-owning white men. Whereas I would agree with one of the main ideas for which historian Christina Proenza-Coles argues in her vital book American Founders: How People of African Descent Established Freedom in the New World (2019): the most inspiring Revolutionary and founding figures were in fact enslaved African Americans. Moreover, these figures don’t just illustrate America’s Revolutionary ideals, they also model the celebratory and critical forms of American patriotism that I trace in my forthcoming book Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism.

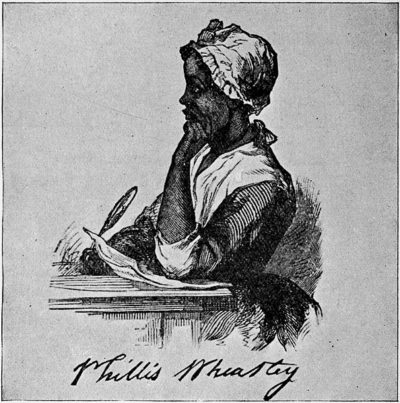

When we talk about patriotism, we often mean “celebratory patriotism,” an emphasis on the nation’s unique and inspiring greatness. One of the Revolutionary period’s most vocal celebratory patriots was Phillis Wheatley, the enslaved young woman and supremely talented poet whose 1770s publications helped shape images of the new nation. In her 1775 poem “To His Excellency George Washington,” Wheatley linked Washington to those celebratory national images, portraying him as a “great chief” fighting for “the land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!” She sent her poem to General Washington at his Cambridge headquarters, and he responded enthusiastically, sharing the poem through a mutual friend with Tom Paine who published it as an exemplary expression of Revolutionary patriotism in the April 1776 issue of his Pennsylvania Magazine.

Moreover, in her 1773 poem “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” Wheatley ties such celebratory images of America’s Revolutionary ideals to her own experiences as an enslaved young woman. Addressed to William Legge, England’s “Principal Secretary of State for North America,” Wheatley’s poem expresses her fervent hope that “Fair Freedom” will once more “adorn” the land, that No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shalt thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’ enslave the land.

Wheatley cites directly her experience of being kidnapped into slavery and away from her home and parents, concluding “Such, such my case. And can I then but pray/Others may never feel tyrannic sway?”

Yet of course in Wheatley’s 1770s Massachusetts, as in every one of the Revolutionary colonies, enslaved African Americans were feeling the tyrannic sway of slavery. A series of Massachusetts enslaved people worked to highlight and challenge that situation directly, and in so doing they modeled an alternative form of patriotism, the category I define as “critical patriotism.” This form of patriotism criticizes the nation’s flaws and failures, highlighting the gaps between American ideals and realities in an effort to help move the nation closer toward a more perfect union that can live up to those ideals.

In January 1777, just six months after the Declaration of Independence, a group of Massachusetts slaves and their abolitionist allies presented a petition to the Massachusetts Legislature that embodied such critical patriotism. The enslaved petitioners called themselves “a great number of Blacks detained in a state of slavery in the bowels of a free and Christian country.” And they noted that “your petitioners cannot but express their astonishment that it has never been considered that every principle from which America has acted in the course of their unhappy difficulties with Great Britain pleads stronger than a thousand arguments in favor of your petitioners.” In appealing directly to the identity and ideals of the new United States, these enslaved petitioners linked their own desire for freedom to that of the Revolutionary nation, potently rebutting Jefferson’s description of slave rebellions as hostile to the cause.

When the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution codified the Declaration of Independence’s sentiments into law, opening its Article I with the phrase “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights,” the enslaved Massachusetts residents Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker pushed such critical patriotic efforts even further, using the law and the courts to argue for their own freedom and help abolish slavery in the state, all within that Revolutionary framework. Freeman, Walker, and their allies turned the nation’s defining ideals from statements to collective realities, making these figures critical patriots and American founders in the truest and most inspiring sense.

As we strive to better remember the American Revolution and founding era, we cannot elide the horrors that are part of our history. But such horrors alone are entirely insufficient to model a path forward, a vision of the nation that can be truly shared by all Americans. Neither can traditional narratives of the founders suffice, as they exclude far too many Americans, both in their own era and in ours. Instead, we need to redefine the Revolution and patriotism alike to document all histories and include all patriots..

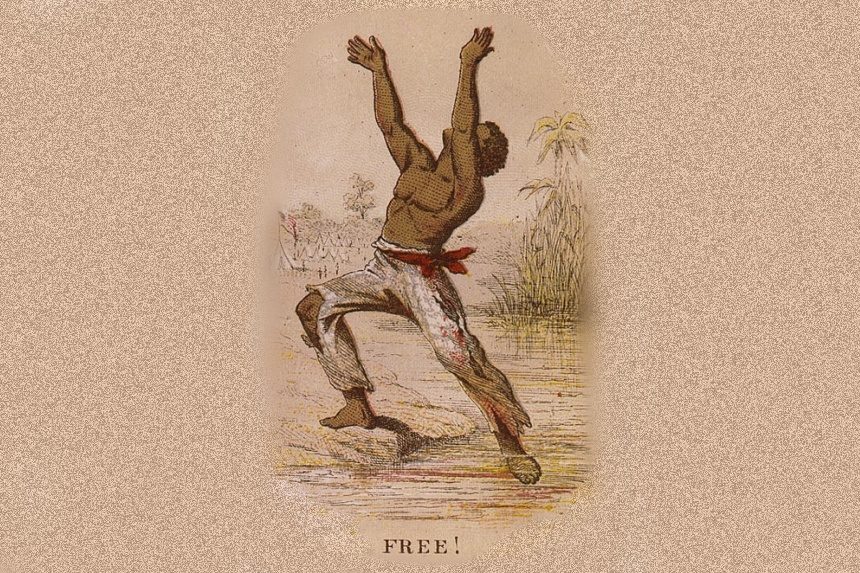

Featured image: Card showing African-American slave reaching freedom (H.L. Stephens, Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Quite frankly the 1619 Project is a bunch of liberal BS being pushed to attempt to replace REAL History. It’s quite sad the idiot President that was elected chose to put an end to the 1776 Commission. But that’s left-wing liberal Democrat politics for you. I was a student of History back in the 1970s and have lived through a lot of History since and have an amazing recollection I am not ashamed to share with others including our youth. I also live and was raised in the rural South and proud of my roots and unashamed how I was raised or educated culminating with an Honors BS Degree from The University of Alabama. This post will likely piss some off while others will applaud what I wrote. It’s sad to see that the Cancel Culture has found a home in the White House. I’ll be much in praise one day when some politician on either side of the aisle and the media work together to CANCEL the Cancel Culture.