This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In recent days, another controversy has erupted around an athlete’s national anthem activism, this time centered on U.S. track and field star Gwen Berry and her decision to protest during the playing of the anthem at her Olympic trials medal ceremony. As was the case during Colin Kaepernick’s anthem protests throughout the 2016 NFL season (and for that matter after Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s 1968 Olympic protest), Berry’s critics have responded to her activism by attacking not just her actions but her patriotism, arguing that she should not be representing the United States (and even should not live in the U.S.) if she is not willing to stand proudly for the anthem and flag.

I’ve argued in this column that Kaepernick’s protests exemplify and extend the legacy of critical patriotism, a category at the heart of my new book on the contested history of American patriotism. I’d say the same of Berry’s actions, and all the athlete activism we’ve seen over the last few years. But all these anthem protests also present an opportunity for us to better remember the ways in which “The Star-Spangled Banner” has consistently featured both celebratory patriotism and exclusionary visions of American identity, from its War of 1812 origins to its early 20th century establishment as the official U.S. national anthem.

As is well known, lawyer and occasional poet Francis Scott Key wrote the lyrics to “Defense of Fort M’Henry” (the poem that he and publisher Thomas Carr would subsequently set to a traditional tune and rename “The Star-Spangled Banner”) while aboard a truce ship in Baltimore Harbor, watching that American fort successfully fend off a British attack on the night of September 13, 1814. The first of the song’s four verses is the only one consistently performed, and focuses (as does the second verse) on that successful defense and specifically on the American flag’s endurance throughout the bombardment and into the following dawn’s early light. Key helped create this celebratory patriotic narrative of perseverance and triumph, one directly tied to the nation’s revolutionary ideals with the closing image of the flag waving “o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

The song’s third verse broadens its focus, however, adding a crucial and complex layer to its expressions of patriotism. The verse depicts the nation’s War of 1812 adversaries not just as the English and their allies, but also as avowed enemies of the very existence of the United States: “that band who so vauntingly swore/That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion/A home and a Country should leave us no more.” This frame reimagines the war, one precipitated by conflicts on the young nation’s periphery (both the Atlantic Ocean and the Northwest frontier), as nothing short of a second American Revolution, a defining struggle in which this idealized new nation is pitted against adversaries whose victory would apparently mean no future for that nation.

Moreover, and much more troublingly, in its second half the third verse depicts those War of 1812 enemies as domestic as well as foreign. Where is that band who sought to end the United States? Key answers that “Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution./No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.” The word “slave” in particular alludes to white Americans’ fears, ones present since the Revolution’s earliest moments but renewed during the War of 1812, that the British would coerce enslaved African Americans to join their cause. As a slaveowner since the age of 21, a Washington, D.C. lawyer who frequently opposed abolitionist efforts in the city, and a founding member (three years after writing “Banner”) of the American Colonization Society, which sought to send free Blacks to Africa, Key was intimately familiar with both the system of slavery and with a vision of American identity that depicted African Americans, enslaved and free, as fundamentally outside of the nation.

A century later, on August 23, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed an Executive Order designating the “Star-Spangled Banner” as “the official hymn of the United States” armed forces and requiring a War Department arrangement to be played by military bands at all formal occasions. Two years later, with the U.S. military now involved in the Great War (later known as World War I), the song was played during the 7th inning stretch of the first game of the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs, cementing its status as a civic as well as military celebratory patriotic anthem.

Wilson’s endorsement of the anthem, however, cannot be separated from his and the era’s broader exclusionary vision of American patriotism and national symbols. In his December 1915 State of the Union address to Congress, Wilson called for passage of the Espionage and Sedition Acts, laws protecting the United States from supposed domestic enemies and critics. Wilson linked these proposed laws directly to xenophobic fears of anti-American immigrant communities, arguing, “There are citizens of the United States,…born under other flags but welcome under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life….I urge you to enact such laws at the earliest possible moment and feel that in so doing I am urging you to do nothing less than save the honor and self-respect of the nation.”

Congress debated and eventually passed the two laws for which Wilson argued, and the 1918 Sedition Act in particular directly tied such exclusionary fears to the protection of national symbols such as the flag. The law defined “sedition” sweepingly enough to include criticism of those national symbols, making illegal “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States…or the flag of the United States.” The Sedition Act was subsequently used to prosecute numerous critics of U.S. policy, from World War I pacifists to journalists like Ida B. Wells to labor movement leaders. It even contributed to the era’s expanded policy of ideological deportation that historian Julia Rose Kraut traces in her recent book Threat of Dissent: A History of Ideological Exclusion and Deportation in the United States (2020).

Attacks on anthem protesters like Gwen Berry as unpatriotic and even un-American in many ways echo the Sedition Act’s exclusionary vision of national symbols like the flag and the anthem. Remembering those histories likewise helps us engage with all aspects of the anthem: From its celebratory patriotic narrative to the anthem’s War of 1812 origin points, to the exclusionary depiction of enslaved African Americans. And it reminds us that protesting aspects of America is not un-American, but rather is an example of the critical patriotism of athlete activists like Berry, Kaepernick, and many others.

Lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner”

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there;

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream:

‘Tis the star-spangled banner, O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.O thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved homes and the war’s desolation.

Blest with vict’ry and peace, may the Heav’n rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

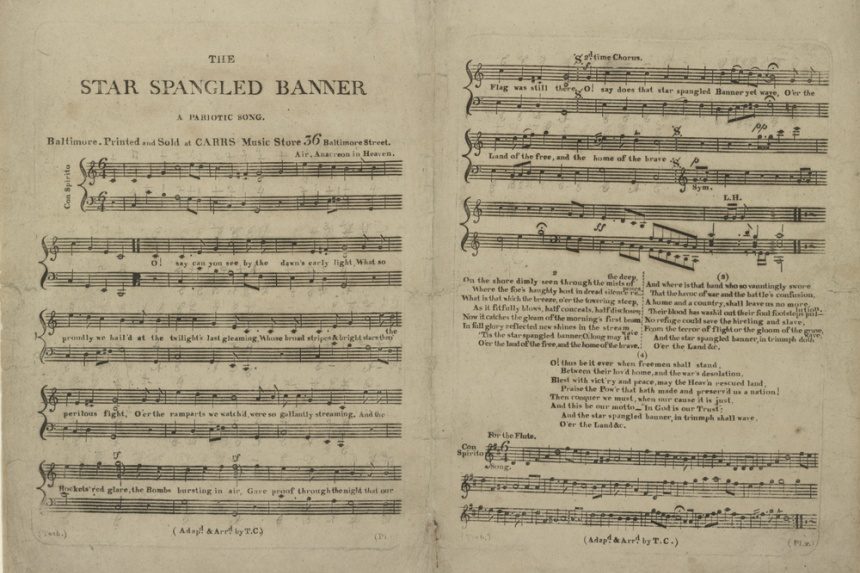

Featured image: The first sheet music publication of “The Star Spangled Banner” by Thomas Carr, 1814 (Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Any new thoughts on this, Ben?

This nation is sooo divided at this point Professor Railton, I’m mentally exhausted from the pedal to the metal trauma and drama on a daily basis from having to worry about almost everything.

Having said that, Ms. Berry’s protest (turning away from the American flag) is one of the least of our problems in and of itself. It is definitely part of the nation’s long-suffering history of race the U.S. has had (and continues to have) with African Americans which undoubtedly will continue for the foreseeable future.

I’m not sure of what her specific reasons were, but she obviously has them. Part of me feels this country has given her the wonderful opportunity to represent the U.S. Track & Field in the summer Olympics and be on the world’s stage, very likely winning a gold medal. All eyes would/will be on her. It could be a rare moment of national pride, unity and healing; little more than a year after George Floyd. He’d be proud, too.

The other part of me feels if she needs to look away, or down, than that’s her decision also; basically what Jen Psaki said. That is her right, and her business. If Republican Dan Crenshaw doesn’t like it, that’s too bad. It should be restated, right here right now, that NO Democrats or Republicans EVER refer to THEMSELVES as AMERICANS!

Oh God no! They’ve got ‘Democrat’ and ‘Republican’ tattooed on their back sides. No, to them ‘Americans’ are ‘The American people’ code for “The pathetic people we hate and are continually working against with all our might. If we could send them all to Auschwitz, we would!” There are exceptions like Senator Bernie Sanders, but only a mere handful. So since they’re not acknowledged Americans themselves, they need to shut up on this, and frankly most everything else.

I really wasn’t familiar with the other verses of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ that (upon study) do have disturbing aspects to them. Thank you for re-printing them here in their entirety. There is plenty for millions of Americans to be unhappy about (of ALL races) today with ‘unofficial’ slavery of economic injustice and near complete inhumanity for our honest, hard working citizens for starters.

People all over the world are painfully aware of this. It’s not exactly a secret. In a different time, Gwen might have just ‘gone along’ with things for appearances sake. Maybe she will at the upcoming Olympics, maybe not. This is a decision that only she can make for herself in the days ahead.