This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

There aren’t many things that can unite most Americans here in March 2023, but the return of the annual ritual of filling out March Madness brackets definitely qualifies. For the next few weeks, we’ll all have strong opinions about whether this is the year Gonzaga finally gets over the hump in the NCAA Men’s Tournament, whether South Carolina can continue its run of historic greatness to a repeat championship in the NCAA Women’s Tournament, whether Oral Roberts will become another unlikely Cinderella story, and so many other storylines that remind us of the complex but undeniably compelling power of sports.

That power can feel like it resides mostly in sports’ ability to entertain us, to provide a communal escape from the more difficult realities of our lives. But I would argue precisely the opposite: not only that sports are influenced and affected by all those realities, but also that sports at their best can play a role in social change and progress. Offering a case study in the social significance of sports is a longstanding and world-famous basketball team that seems designed solely to entertain: the Harlem Globetrotters.

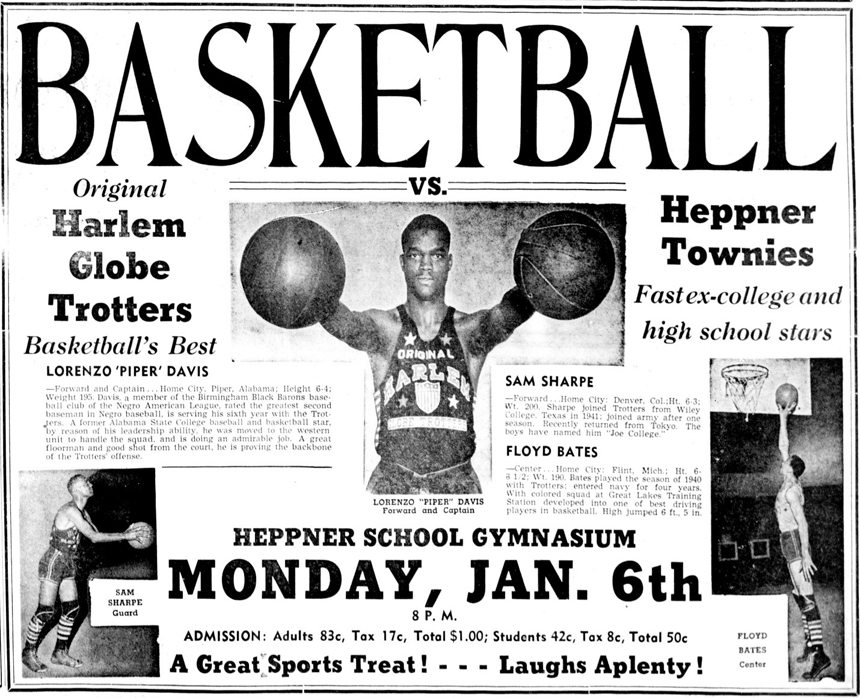

The creation and the naming of the Globetrotters both reflect historical realities of race and prejudice and exemplify the team’s goal of transcending them. In the 1920s, decades before the founding of the National Basketball Association, most organized basketball in America took place at the collegiate level, and the vast majority of those college teams were racially segregated. Many of the best Black basketball players thus had to look elsewhere for opportunities to play, and one such opportunity was offered by Chicago’s Savoy Ballroom: not long after its 1927 opening, the Ballroom began fielding an exhibition basketball team known as the Savoy Big Five in order to draw crowds to its dances. Local entrepreneur and longtime basketball player and coach Abe Saperstein learned of the group and signed on as a manager and promoter, and in 1929 he and the team began to tour the region.

As the team broadened its horizons beyond the Savoy Ballroom and Chicago, it needed a name that would reflect those aspirations. In the 1920s, no American community better embodied the vibrancy of African American culture, of the Jazz Age and the Roaring ’20s, and of an increasingly cosmopolitan and globally connected nation than did the New York neighborhood of Harlem and its unfolding Harlem Renaissance. Despite the team’s Illinois roots and initial Midwestern tours, Saperstein and the Savoy players recognized their own connection to those cultural, national, and cosmopolitan trends, and chose a new team name that echoed those trends: the New York Harlem Globe Trotters.

After an initial decade of successes at the regional level, during which the team began to incorporate more humor and showmanship thanks to stars like Inman Jackson, a pair of 1940s victories truly established the Globetrotters as a force on the national and global basketball landscape. Beginning in 1939, Chicago played host to an annual invitational competition known as the World Professional Basketball Tournament, which was often dominated by teams from the recently created and racially segregated National Basketball League (NBL) but which was open to other professional teams as well. In 1940’s second World Professional Basketball Tournament, the Globetrotters secured the crown, capping the tournament’s only undefeated run by besting the all-white Chicago Bruins 31 to 29 in the championship game.

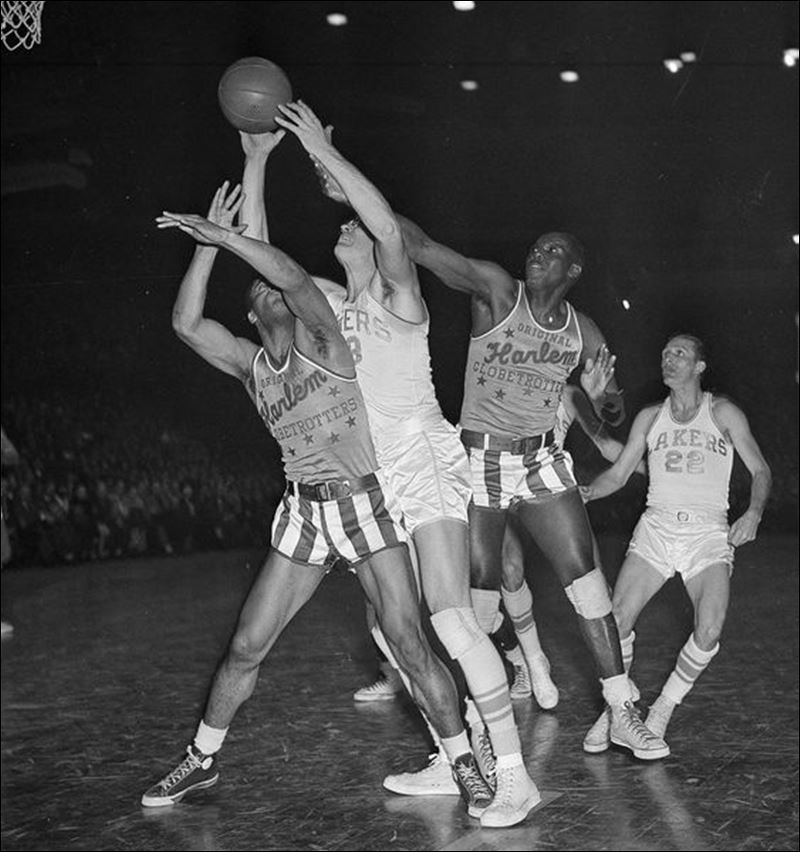

That tournament victory was certainly significant, but it was an even more high-profile triumph a few years later that really launched the Globetrotters into the national basketball conversation. One of the best and most prominent basketball teams in the late 1940s was the Minneapolis Lakers, an all-white team that dominated league play in the era (first in the NBL and then in the newly-created and still segregated Basketball Association of America [BAA]). Lakers general manager Max Winter was friendly with Abe Saperstein, and the two decided to stage an exhibition game between the teams. The Globetrotters arrived at that February 1948 contest on a 102-game winning streak, but they had never faced competition like the Lakers, which featured two future Basketball Hall of Famers including superstar George Mikan. As historian John Christgau traces in his book about this 1948 game, the Globetrotters also dealt with segregated conditions far beyond the basketball court, as the night before the game they slept in tiny rooms in Ma Piersall’s South Side boarding house, while the Lakers stayed at the luxury Morrison Hotel.

The game was a tight and back-and-forth affair, with Mikan and Globetrotters star Reece “Goose” Tatum largely canceling each other out, but in the end the Globetrotters triumphed on a buzzer-beater by Ermer Robinson. (The Globetrotters would more handily win a rematch between the two teams the following year.) While both Saperstein and Winter publicly denied that the game had anything to do with race, the victory certainly meant a great deal to both Black basketball players and the broader African American community. John Chaney, the future Hall of Fame basketball coach at Temple University, was a teenager in Jacksonville, Florida at the time, and on the game’s 60th anniversary reflected that the victory “just revitalized so many of us, from the fact that it showed what we can be, but we needed a chance.”

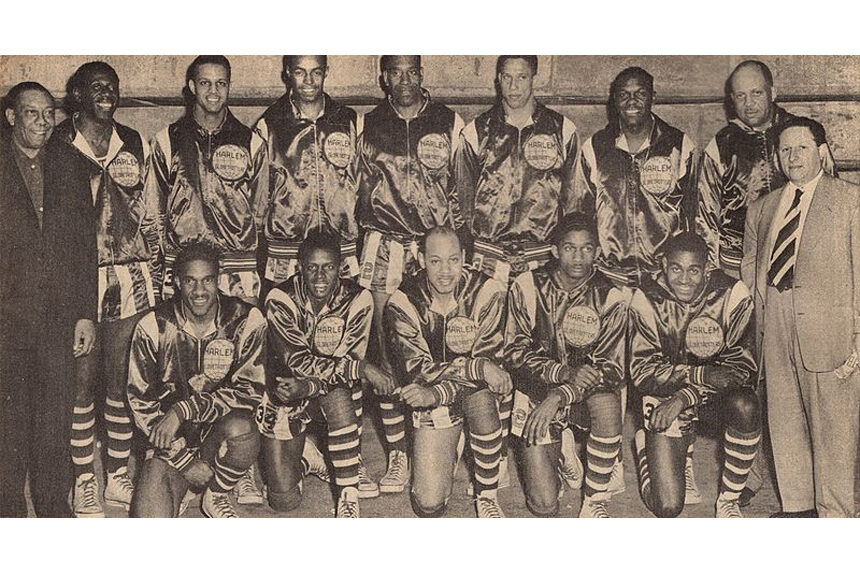

The Globetrotters’ successes also directly contributed to the desegregation of professional basketball in America and around the globe. The BAA changed its name to the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1949, and as that league expanded in 1950 three of its teams drafted the first three Black players, all drawn from the Globetrotters: Chuck Cooper went to the Boston Celtics, Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton to the New York Knicks, and Hank DeZonie to the Tri-Cities Blackhawks.

Later in that decade, one of the era’s most talented and prominent basketball players, Wilt Chamberlain, joined the Globetrotters after his hugely successful college career at Kansas and before becoming one of the NBA’s all-time great players. During Chamberlain’s 1958-59 stint with the Globetrotters he and the team embarked on a sold-out tour of the Soviet Union, reflecting the team’s truly international (if controversial) influence by this time.

The Harlem Globetrotters have always been far more than just a comic exhibition team, just as basketball and sports have always meant much more than simply entertainment or escapism. The social significance of this team and sport alike embody the best of what American sports can mean and do, and deserve a prominent place in any American history tournament bracket.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Every year in March in the 50s and early 60s my father for my birthday would take the family to watch the Harlem Globetrotters play in Miami. What a joy it was to watch to watch Meadowlark Lemon and the rest of the team do what they did on the court, fond memories.

I would like to see the Globetrotters in a non-fixed, exhibition match-up with the winners of the NCAA Tournament, NIT Tournament, and NBA Championship Teams. Let’s see what they are made of nowadays.

No mention of Meadowlark Lemon and the ensuing years of the Globetrotters?

An incredibly talented team. Seen in person, and many times on TV. Thanks for this piece.

Excellent Black History