This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

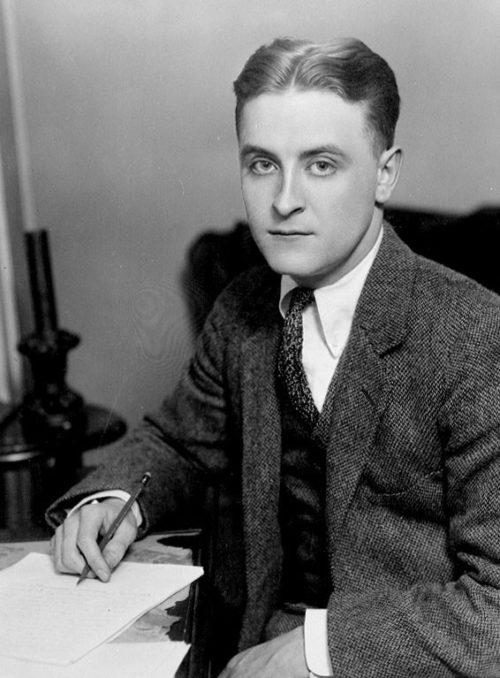

On April 10th, 1925, the first edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby was released in the United States. Originally published to mixed critical reviews and mid-level sales at best, over time Gatsby has become one of the most acclaimed and well-read American novels. It is often located close to the top of “Best of the 20th Century” lists, is a perennial contender for the elusive title of The Great American Novel, and is one of the most frequently taught texts in American classrooms. While Fitzgerald did not choose to go with the alternate title Under the Red, White, and Blue, there’s no question that his book has become closely linked to images of American identity and community—and to national narratives such as the American Dream.

Fitzgerald’s novel is also closely connected with its time period and cultural moment, and specifically with images of the “Roaring Twenties.” The novel’s depictions of wealth, excess, recklessness, the interconnected cultures of alcohol and organized crime during Prohibition, and new technologies like automobiles and Hollywood silent films, have become synonymous with that era between World War I and the Great Depression. Yet while Gatsby certainly captures those historical and cultural contexts, there are many other sides to 1925 America that are much less central to its world. There are other books published in 1925 that can better connect us to those histories and add them into our collective memories of the era.

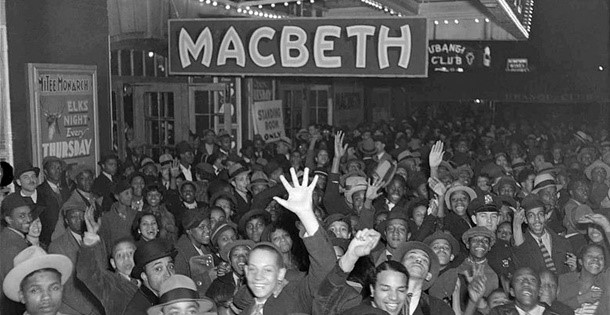

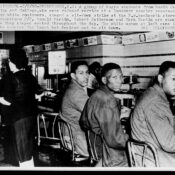

Perhaps the most striking historical absence from Fitzgerald’s novel is that of African Americans and the nascent Harlem Renaissance. As part of the first wave of what came to be known as the Great Migration, large numbers of African Americans had been migrating to New York City for more than a quarter-century, and the upper Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem was by 1925 one of the nation’s most vibrant African American communities. Many of New York’s white socialites were frequent visitors to and patrons of the jazz clubs, parties, and social events that came to embody the relationship between that Harlem world and the city around it. Yet despite its New York setting, Fitzgerald’s novel does not reference Harlem at all — indeed, the book’s only African American characters are a stereotypical trio of “three modish negroes, two bucks and a girl,” whom the narrator Nick Carraway observes in a passing car, “the yolks of their eyeballs roll[ing] toward us in haughty rivalry.”

Providing an important corrective to that absence is another ground-breaking 1925 book, The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Assembled and edited by the philosopher, educator, and activist Alain Locke, The New Negro features a broad and varied collection of African American creative writers, scholars, historians, journalists, and visual artists, highlighting the wide range of forms, topics, and contexts to which this developing Harlem community had already connected. From the first published story by Zora Neale Hurston (who was about to enter Barnard College) to some of the earliest published poems by Langston Hughes, along with contributions from established authors and leaders such as James Weldon Johnson and W.E.B. Du Bois, The New Negro reflects a burgeoning African American, New York, and national community that existed alongside Gatsby’s world but offers a very different side to America in 1925.

In the political realm, many of the most prominent and divisive 1925 debates focused on the interconnected topics of immigration and national identity. Coming at the culmination of a four-decade period of particularly significant waves of immigration, the 1921 Emergency Quota Act and 1924 Quota Act had enshrined exclusionary, white supremacist attitudes in national immigration law. As South Carolina Senator Ellison DuRant Smith put it in a Senate speech in support of the 1924 law, “It seems to me the point as to this measure … is that the time has arrived when we should shut the door. … Thank God we have in America perhaps the largest percentage of any country in the world of the pure, unadulterated Anglo-Saxon stock … and it is for the preservation of that splendid stock that has characterized us that I would make this not an asylum for the oppressed of all countries.” Debates over these laws and policies, and whether for example to extend them to immigrants from Mexico and other Western Hemisphere nations (initially not included in the 1924 Act), continued throughout the remainder of the decade.

Fitzgerald’s novel does include such a white supremacist and xenophobic voice in the character of Tom Buchanan, and particularly his unhinged Chapter 1 rant about how “civilization’s going to pieces” and “if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged.” Tom is as close as the novel has to a villain, and by linking him to these bigoted views Fitzgerald certainly makes a clear point about those national debates. But although New York City was one of the most consistent destinations for the era’s immigrant arrivals (and had been since the late 19th century), Gatsby does not feature any overtly immigrant or even particularly ethnic American characters. Indeed, its only such minor character is Meyer Wolfsheim, the “small, flat-nosed Jew” to whose illicit and criminal activities Jay Gatsby is connected in unclear but unsavory ways and who is at best a stereotypical character of Jewish and Jewish American identity.

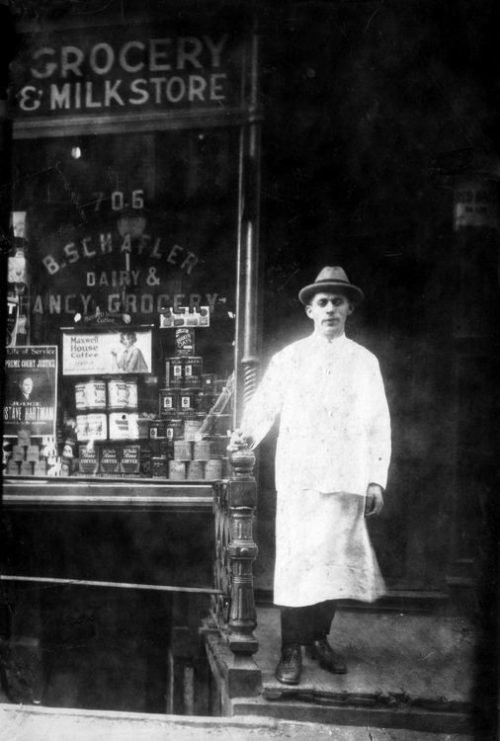

To read about the very distinct images of Jewish immigrants to New York City and Jewish American identities, read Anzia Yezierska’s Bread Givers. This compelling and ground-breaking 1925 novel offers is narrated by Sara Smolinksy, the daughter of Polish Jewish immigrants whose perspective and story we follow from age 10 through her graduation from college and subsequent professional and personal developments. Through Sara’s eyes we see the challenges facing a multi-generational Jewish American immigrant family (with a father determined to maintain his role and identity as an Orthodox Talmud scholar), the communal setting of the Lower East Side’s tenements, and the possibilities and limitations of assimilation into American society for a second-generation immigrant such as Sara.

On the anniversary of Gatsby’s publication, adding books like Bread Givers and The New Negro to our reading list can only help contextualize and expand the world and meanings of Fitzgerald’s classic novel.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for the comments, Bob! I agree about Gatsby as a novel rather than a panorama, but I would argue that many readers and Americans have come to see it as that kind of historically representative text, which is why I wanted to push back on it in these particular ways.

On the Great American Novel topic, I actually just wrote a week-long blog series on other nominees for that complicated category, which starts here if you’re interested:

http://americanstudier.blogspot.com/2018/04/april-9-2018-great-american-novel.html

Thanks,

Ben

As alluded to, it’s that miracle, a literally ( pun if you find it to be so ) perfect work of art. Not a single false move by Fitzgerald.

“The Great Gatsby,” is a novel, not a panorama of the times, and hands down, it’s The Great American Novel, with “Huckleberry Finn,” a close second, and “Moby Dick” its own weird, glorious thing.

Thanks so much for that very thoughtful comment, Bob! Adding all of our voices and perspectives into the conversation is another vital thing for us to do and I really appreciate your doing so as well.

Ben

Really good feature (including the links) that shines a light on different aspects of the ’20s that are overlooked, forgotten or intentionally left out when we think of the decade.

Although ‘The Great Gatsby’ contains tragic elements, it still leaves you with the feeling the decade was better than it really was. The glitz and glamour of the rich combined with the VERY unique looks/fashion/music of the decade can easily seduce one into the false notion a splendid time was guaranteed for all, which was hardly the case.

The economy after World War I was not equivalent to the post World War II economy for the average American. In addition, there were those at the top using Wall Street as their personal Monte Carlo casino which eventually led to the terrible Crash in late 1929, where there were so many suicides.

Nothing ever happens overnight though. My grandfather lost his business on Friday, January 13, 1928—–the day my mother was born. She had a very rough childhood in the ’30s, which I’m still very aware of to this day. In an ironic twist of fate, the economy started booming again in 1946 (at 18) as an adult. With me, it was the opposite.

I had a wonderful childhood that made life seem easy, but the economy for the average American started to go bad when I was 16 (’73-’74) and has never returned to anything comparable to the 1946-’72 postwar period; not even CLOSE!

In large part what’s saved the ’20s in popular culture were the Depression years of the ’30s. The 20’s have been frozen in time. Occasionally there are TV ads depicting the 20th century which go from the Roaring’20s to the sailor kissing the nurse, as if the years in between never happened.

The stories of African Americans and their contributions here like ‘The New Negro’ help to present a more balanced view of U.S. life. Immigration too, of course. It’s evident this country’s struggles aren’t going away, so ‘The Great Gatsby’ will continue to provide a romantic (if flawed) view of the ’20s, and that’s okay as long as you keep it in perspective. Thank you Professor Railton for doing just that.