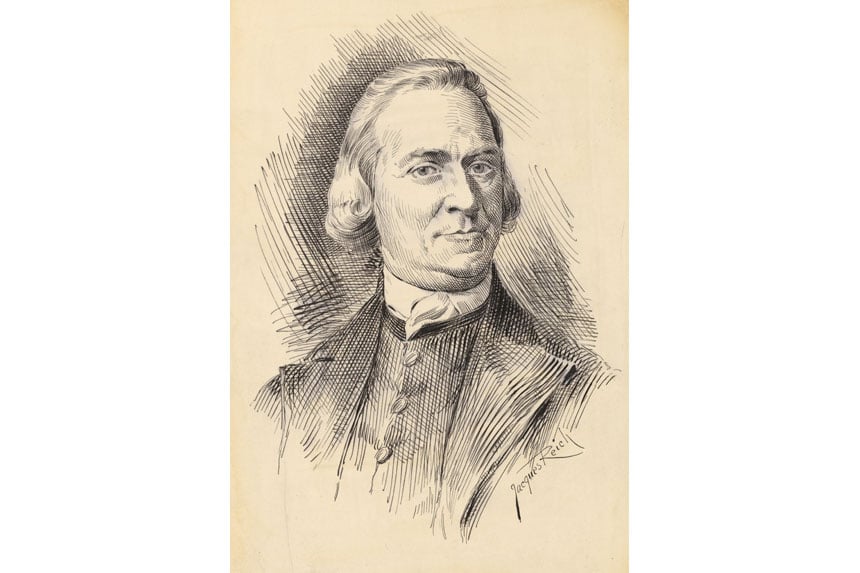

Before his first inaugural address, Thomas Jefferson asked himself: “Is this exactly in the spirit of the patriarch of liberty, Samuel Adams?” Would he approve of it?

To understand why the new president hoped to channel Adams’s spirit is to discover not only where a daring revolutionary came from, but where a revolution did. To lose sight of him is to lose sight of a man who calculated what would be required to upend an empire, and who — radicalizing men, women, and children with boycotts and pickets, street theater, invented traditions, a news service, a bit of character assassination, and any number of innovative, extralegal institutions — led American history’s seminal campaign of civil resistance. Adams banked on the sage deliberations of a band of hard-working farmers reasoning their way toward rebellion. That was how democracy worked.

Samuel Adams delivered what may count as the most remarkable second act in American life. It was all the more confounding after the first: He was a perfect failure until middle age. He found his footing at 41, when, over a dozen years, he proceeded to answer to Thomas Jefferson’s description of him as “truly the man of the Revolution.” With singular lucidity Adams plucked ideas from the air and pinned them to the page, layering in the moral dimensions, whipping up emotions, seizing and shaping the popular imagination.

On a wet 1774 night when a group of Massachusetts farmers settled in a tavern before the fire and, pipes in hand, discussed what had driven Bostonians mad — reasoning that Parliament might soon begin to tax horses, cows, and sheep; wondering what additional affronts could come their way; and concluding that it was better to rebel sooner rather than later — it was because the long arm of Samuel Adams had reached them. He muscled words into deeds, effecting, with various partners, a revolution that culminated, in 1776, with the Declaration of Independence. It was a sideways, looping, secretive business. Adams steered New Englanders where he was certain they meant, or should mean, to head, occasionally even revealing the destination along the way. As a grandson acknowledged: “Shallow men called this cunning, and wise men wisdom.” The patron saint of late bloomers, Adams proved a political genius.

His second cousin John swore that Samuel was born to sever the cord between Great Britain and America. John also believed Samuel an original; he mystified even his peers. Committed, as he termed it, to “the cool voice of impartial reason,” Samuel Adams breathed fire when fire-breathing was in order. Serene, sunny, tender, he seemed instinctively to grasp what righteous anger could accomplish. From four feckless decades he emerged intensely disciplined, an indomitable master of public opinion — a term yet to be coined. In a colony from which, as a Crown officer observed, “all the smoke, flame, and lava” erupted, Adams seemed everywhere at once. If there was a subversive committee in Massachusetts, he sat on it. If there was a subversive act, he was somewhere near or behind it. “He eats little, drinks little, sleeps little, thinks much, and is most decisive and indefatigable in the pursuit of his objects,” noted a Philadelphia colleague, unhappily.

His enemies, insisted Adams, came in handy: “Our friends are either blind to our faults or not faithful enough to tell us of them.” He knew that we are governed more by our feelings than by reason; with rigorous logic, he lunged at the emotions. He made a passion of decency. He was a prudent revolutionary. Among the last of his surviving words is a warning to Thomas Paine: “Happy is he who is cautious.”

Deeply idealistic — a moral people, Adams held, would elect moral leaders — he believed virtue the soul of democracy. To have a villainous ruler imposed on you was a misfortune. To elect him yourself was a disgrace. At the same time, he was unremittingly pragmatic. Adams saw no reason why high-minded ideals should shy from underhanded tactics. Power worried him; no one ever believed he possessed too much of the stuff. His sympathies lay with the man in the street, to whom he believed government answered. A friend distilled his politics to two maxims: “Rulers should have little, the people much.” And privilege should make way for genius and industry. Railing against “the odious hereditary distinction of families,” Adams fretted about vanity, foppery, and “political idolatry.” He did his best to contain himself when John Hancock — who traveled with “the pomp and retinue of an Eastern prince” — appeared in a gold-trimmed, crimson-velvet waistcoat and an embroidered white vest. In 1794, Adams was inaugurated as governor of Massachusetts. To maintain ceremonial standards, a benefactor produced a carriage. Adams directed the coachman to drive his wife to the State House, to which he proceeded, at 71, on foot.

On no count did he mystify more than in his disregard for money. “I glory in being what the world calls a poor man. If my mind has ever been tinctured with envy, the rich and the great have not been its objects,” he wrote his wife of 16 years, who hardly needed a reminder. At a precarious point, she supported the family. Having dissipated a fortune, having run a business into the ground, having contracted massive debts, Adams lived on air, or on what closer inspection revealed to be the charity of friends. A rarity in an industrious, hard-driving, aspirational town, he was the only member of his Harvard class to whom no profession could be ascribed. Certainly no one turned up at the Second Continental Congress as ill-dressed as Adams, who for some weeks wore the suit in which he dove into the woods near Lexington, hours before the battle. It was shabby to begin with. Alone among America’s founders, his is a riches-to-rags story.

There was an elemental purity about the man whom Crown officers believed the greatest incendiary in the king’s dominion. Puritan simplicity never lost its appeal. Afflictions invigorated. Adams handily beat Ben Franklin at Franklin’s 13-point project for arriving at moral perfection. On meeting Samuel Adams in the 1770s, a foreigner marveled: It was unusual, in life or on the stage, for anyone to conform so neatly to the role he played. Here was what a republican looked like. “A man wrapped up in his object,” Adams disappeared into the part, from which it is difficult to pry him, identical as he was to his ideals.

In July 1774, newly arrived in London and reeling still from seasickness, the royal governor of Massachusetts was whisked off for a private interview with George III. For two hours Thomas Hutchinson briefed his sovereign on American affairs. The king seemed as eager to show off his knowledge as to learn what was happening in the most unruly of his American colonies. He asked about Indian extinction and the composition of New England bread. He had heard of Samuel Adams but had not grasped that he was the cause of so many royal headaches. Hutchinson revealed that Adams was “a great man of the party.” What gave him his influence? inquired the king. “A great pretended zeal for liberty, and a most inflexible natural temper,” explained Hutchinson, adding that Adams had been the first to advocate for American independence.

Making the same point differently, Thomas Jefferson called Adams “the earliest, most active, and persevering man of the Revolution.” For many years it was possible to assert that he ranked with, if not above, George Washington. His fame spread alongside New England obstreperousness, which he hoped to make contagious. “Very few have fortitude enough,” he wrote, neatly summarizing his life’s work, “to tell a tyrant they are determined to be free.” Various patriots made their mark as the Samuel Adams of North Carolina, the Samuel Adams of Rhode Island, or the Samuel Adams of Georgia. “The character of your Mr. Samuel Adams runs very high here. I find many who consider him the first politician in the world,” reported a Bostonian from 1774 London.

John Adams met with a hero’s welcome when he arrived in France four years later to solicit funds for the war. He hurried to clarify: He was not the renowned Mr. Adams. That was another gentleman. (No one believed him.) “Without the character of Samuel Adams,” declared John Adams, “the true history of the American Revolution can never be written.”

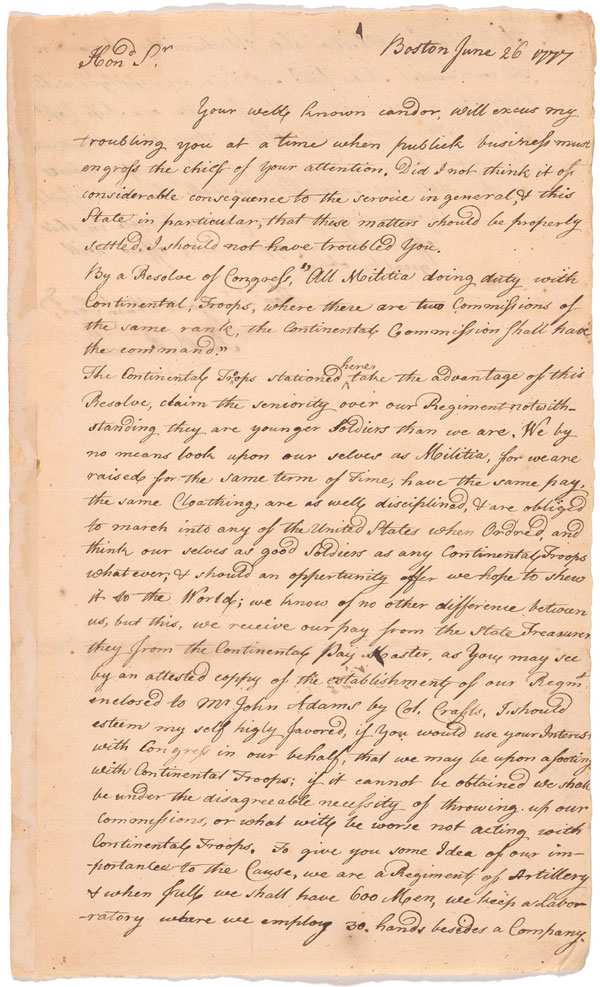

And yet it was, for various reasons. Adams engaged in a delicate, dangerous business. As the font of “thoughts which breathe, and words which burn,” he was in the eyes of the British administration for years a near-outlaw, ultimately an actual outlaw. Had events turned out differently, he would have been first to the gallows. Much of his work depended on plausible deniability; he covered tracks and erased fingerprints. He made no copies of his letters. (One example: Adams and Paul Revere must have been in frequent touch. Two notes between them survive.) John Adams watched helplessly in 1770s Philadelphia as his cousin fed whole handfuls of papers to the fire in his room. Was he perhaps overreacting? asked John. “Whatever becomes of me,” Samuel explained, “my friends shall never suffer by my negligence.” In the summer he had no fire; with scissors, he cut bundles of letters to shreds and scattered the confetti from the window, sparing his associates if stopping the biographer’s heart. A portion of what he did not manage to destroy met with some shameful mistreatment, of which we have only hints. Even a complete record would neither adequately answer the king’s question nor illuminate Adams’s tactics. He operated by stealth, melting into committees and crowd actions, pseudonyms and smoky back rooms. “There ought to be a memorial to Samuel Adams in the CIA,” quips a modern historian, dubbing him America’s first covert agent. We are left to read him in the twisted arm, the borrowed set of talking points, the indignation of America’s enemies. We know more about him from his apoplectic adversaries than from his friends, sworn to secrecy.

Unlike his contemporaries, Adams did not preen for posterity. He wrote no memoir, resisting even calls to assemble his political writings. He consigned the history to others, with predictable results, the more so as his ideas diverged from those of post-Revolutionary America, leaving him intellectually homeless. Sometimes history blossoms after the fact — where a Massachusetts boulder or a Virginia cherry tree might suddenly insert itself into the record — and sometimes it evaporates. Adams escaped the golden haze that settled around his fellow founders, as if it were too extravagant for him. He hailed from the messy, anarchic, provocative years. It would not help that he would be confused with John, who collected his letters, wrote prolifically for the record, and, since adolescence, had rehearsed for greatness.

Samuel Adams was rare for his ability to keep a secret, any number of which he took to the grave, including the backstory of the Boston Tea Party, which he knew as well as anyone. (Dryly he noted that some individuals enjoyed every political gift except that of discretion.) He freely discussed his limitations, reminding friends that he understood nothing of military matters, commerce, or ceremony, though Congress charged him, at various times, with all three. Most of America’s founders became giants after independence. Adams began to shrink. A cloud of notoriety survives him; the fame does not. He would be minimized in any number of ways. He was called many names in his life but one thing he was never called was “Sam.” He is the sole signer of the Declaration of Independence to come down to us as an incendiary, and a beer.

A Pulitzer Prize-winner, Stacy Schiff is the author of several bestselling biographies and historical works, including Cleopatra: A Life, and, most recently,The Witches: Salem, 1692. Schiff has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New York Review of Books, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Los Angeles Times, among many other publications. She lives in New York City.

Excerpted from the book The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams by Stacy Schiff. Copyright © 2022. Available from Little, Brown, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

This article is featured in the July/August 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Samuel Adams was a tremendous force to be reckoned with that without whom, we clearly would not have won our Independence in 1776. How horrified he’d be today to learn America’s own government is working against its own people far more than England ever did in the 18th century, or possibly could do.