This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This past weekend saw the release of one of the year’s most anticipated and acclaimed films, Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. The film has not been without pre-release controversy, however. Much of it is centered on the question of whether the movie foregrounds white characters such as Leonardo DiCaprio’s Ernest Burkhart at the expense of minimizing the Native Americans at the heart of the story of the Osage murders. The film’s source material, David Grann’s book of the same name, has been similarly critiqued at times for focusing more on the FBI’s investigations of those murders than on their indigenous victims.

No matter what else it does or doesn’t do, this blockbuster film from one of the most successful directors in film history can help draw further attention to the Osage murders and the longstanding history of Native Americans in Oklahoma. That history represents far too consistently the worst of America’s white supremacist exclusions, discriminations, and violence. But it also features two court decisions that reflect the potential for justice for Native Americans.

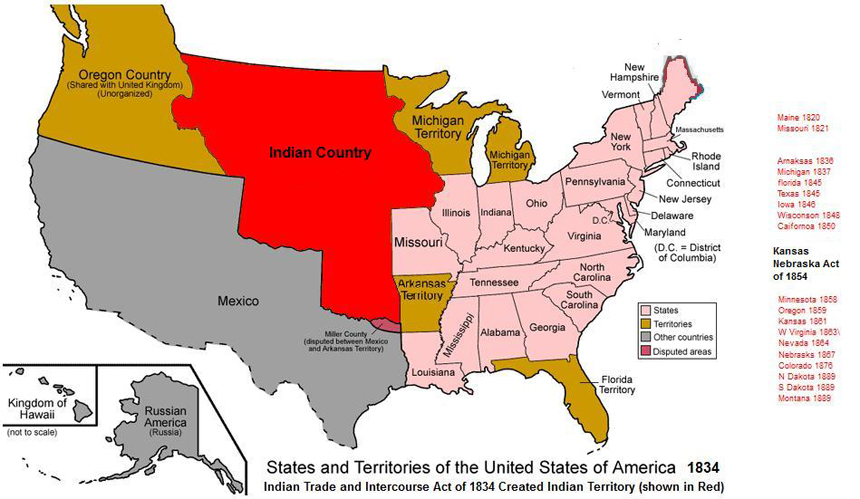

Long before it bore the name Oklahoma, the area was part of a sizeable region of the expanding United States known as Indian Territory. When President Thomas Jefferson acquired a great deal of the eastern half of the continent through the Louisiana Purchase (1803), he planned to reserve the lands east of the Mississippi River for European American settlement and the lands west of the river for Native Americans. For a couple decades those plans were largely hypothetical, but President Andrew Jackson’s early 1830s Indian Removal policy made them very real: tens of thousands of members of the five Southeastern tribes were forced to march more than 5,000 miles to resettlement in Indian Territory, a brutal and horrific process that became known as the Trail of Tears. Those that survived the Trail were promised a permanent home in this region, one to which other removed tribes were likewise sent in subsequent decades.

Like every other U.S. government promise to Native American tribes, however, that one was significantly modified and worsened over time. In the first few decades of Indian Territory’s populated existence, the U.S. dealt with the tribes living there through treaties, recognizing their independent status. But in the aftermath of the Civil War, with more and more Americans seeking to move west and this land becoming more desirable as a result, Congress passed the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act, which held that “hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty.” While the Supreme Court ruled in 1886’s United States v. Kagama that this shift was “necessary to [Native Americans’] protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell,” the reality was that the new law gave the federal government plenary power: complete and absolute legal authority over Native Americans.

As Indian Territory was carved up into new territories (and eventual states) for white settlement, the government used that plenary power most consistently to take land away from Native Americans. It did so in part through additional federal laws such as the 1887 Dawes Act, which supposedly encouraged Native American private land ownership and farming but in practice resulted in constant land appropriations by the government. But it did so even more blatantly through land runs that opened up wide swaths of land — all still promised to Native Americans — for arriving white settlers, usually in a first-come, first-served chaos of land grabs. The most famous such land run happened in April 1889 in the newly renamed Oklahoma Territory (even more famously, many of the 50,000 white settlers taking part in that 1889 Land Rush could not even wait for the official April 22nd opening and sneaked onto the land early). These “Sooners,” settlers who perpetrated land grabs and thefts even more aggressively than their peers, became the mascot of Oklahoma’s most prominent institution of higher education, the University of Oklahoma.

While such official appropriations and chaotic land runs took a great deal of Native American land for white settlers, some was still occupied by Native Americans on federal reservations. In 1896, less than a decade after the 1889 Land Rush, oil was discovered on one of those Native American communities, the Osage Reservation in Osage County, Oklahoma. The federal government took its own steps to attempt to appropriate that oil and the wealth it produced, passing a law in 1921 requiring court-appointed guardians for every Osage resident until they could prove their “competency.” But by that time an even more direct and sinister campaign was underway to rob the Osage through crime and violence: between 1918 and 1931 at least 60 Osage were murdered, a period that became known as the Reign of Terror. This extreme time of murder and theft is the subject of Killers of the Flower Moon, but it was unfortunately all too typical of the Native American experience in Oklahoma and Indian Territory for well more than a century.

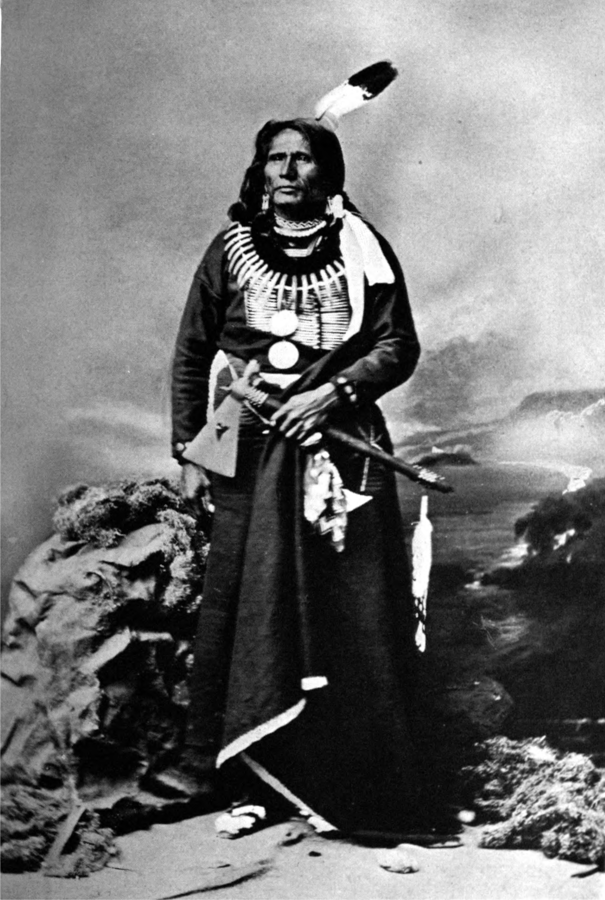

As Grann’s book recounts at length, the quest to solve the Osage murders was one of the FBI’s earliest efforts. But Oklahoma also figures in two court cases, one in the late 19th century and one from our own era, that reflect the potential for justice for Native Americans after these centuries of wrongs. I wrote about the first of those cases, Standing Bear v. Crook (1879), in this October 2018 Considering History column on Native American citizenship. Chief Standing Bear and the rest of his Ponca tribe had been removed from their Nebraska homeland to Oklahoma, and his son had died on the arduous journey; when he sought to return his son’s remains to Nebraska, he was arrested and imprisoned for illegally leaving that Oklahoma reservation. Standing Bear sued General Crook, the U.S. military officer who had arrested him, and won a vital legal victory, with Federal Judge Elmer Dundy ruling that “an Indian is a person” and entitled to the same “inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as all Americans.”

Standing Bear’s victory helped guarantee Constitutional rights for individual Native Americans, but of course the story of Oklahoma and Indian Territory is also one of the denial of land rights and homelands for entire communities and tribes. And on that level, a surprising recent Supreme Court decision offers the possibility of collective justice. In 2020’s McGirt v. Oklahoma, the Court ruled that much of the land that had been gradually taken from Native American tribes had indeed been promised to them “in perpetuity,” under treaties that have never been rescinded, and returned more than 3 million acres of such stolen land to the Muscogee Creek nation. As scholars Robert Miller and Robbie Ethridge argue in their recent book A Promise Kept: The Muscogee (Creek) Nation and McGirt v. Oklahoma (2023), this decision might help reverse the centuries of theft and discrimination, offering Native Americans the hope of justice and equality under the law, the best of American ideals.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now