In the late 1920s, invitations to Hearst Castle were coveted treats. Hollywood’s elite — a mainstay at newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst’s estate — took a train from Los Angeles at 6:30 p.m. on Friday and arrived at San Luis Obispo around midnight. After breakfast, limousines arrived to shuttle them 45 miles northwest to San Simeon, a small town along California’s Central Coast.

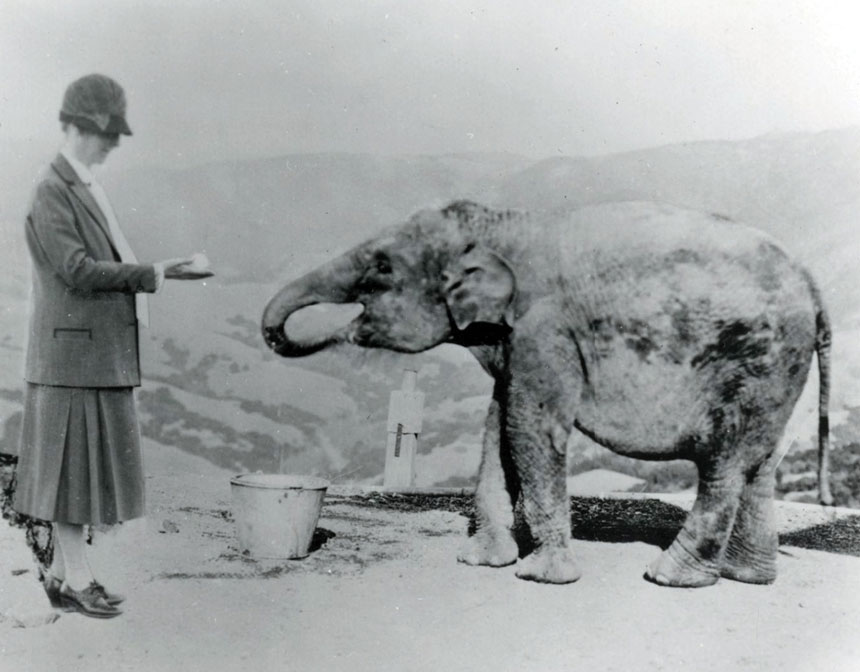

From there, the journey continued on a dirt road that climbed through the foothills near the Santa Lucia Mountains. Depending on the clouds, guests might glimpse the “castle” on a hill overlooking San Simeon Bay, but they were just as likely to see American bison, white fallow deer, kangaroos, and other herbivores roaming the hills. More animals, including cougars and chimpanzees, appeared in a roadside zoo as the drive continued.

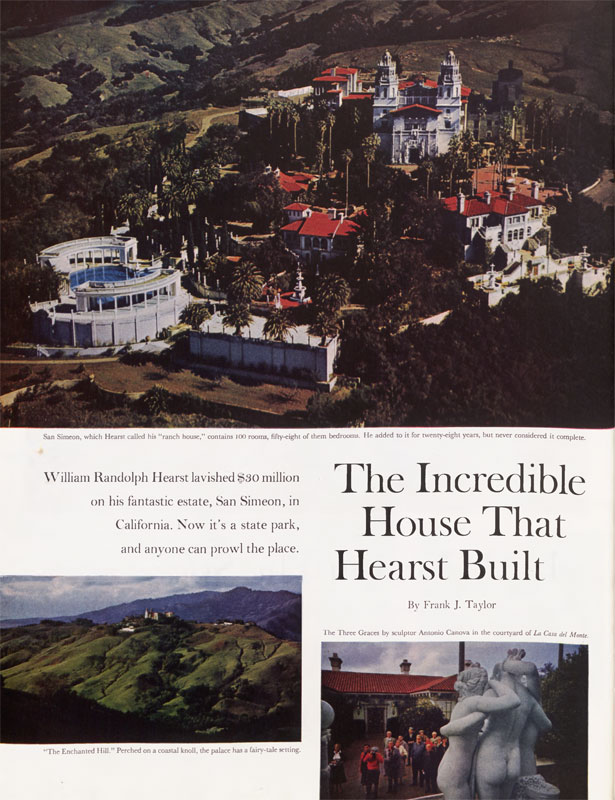

It was Hearst’s version of shock and awe, and the animals were just the beginning. At the estate, classical art greeted visitors at every turn — and still does today — displayed at the two swimming pools, the 120 acres of gardens, and the interiors of Casa Grande, the estate’s cathedral-like main building. Hearst Castle also had a library filled with more than 5,000 books, a 53-seat indoor movie theater, and, later, an airstrip.

To receive a summons, guests had to be interesting, or at least entertaining. Charlie Chaplin was a favorite, as were actors like Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, Cary Grant, and Joan Crawford. However, the visitors log at Hearst Castle wasn’t just a who’s who of Hollywood. Winston Churchill accepted Hearst’s invitation, Amelia Earhart flew to the ranch, and H.G. Wells made his way to the estate. Hearst expected visitors to swim, play tennis, ride horses, and enjoy the outdoors.

Cara O’Brien, museum director at Hearst San Simeon Historical Monument, says Hearst built his estate so he could entertain alongside his mistress, Marion Davies, but he also saw it as an opportunity to educate his guests about the buildings’ architecture, his fine art collection, and the land.

“This is an exquisite building, filled with exquisite artwork, on the most exquisite part of the California Coast,” O’Brien explains. “It has such a great story and so much history and artwork.”

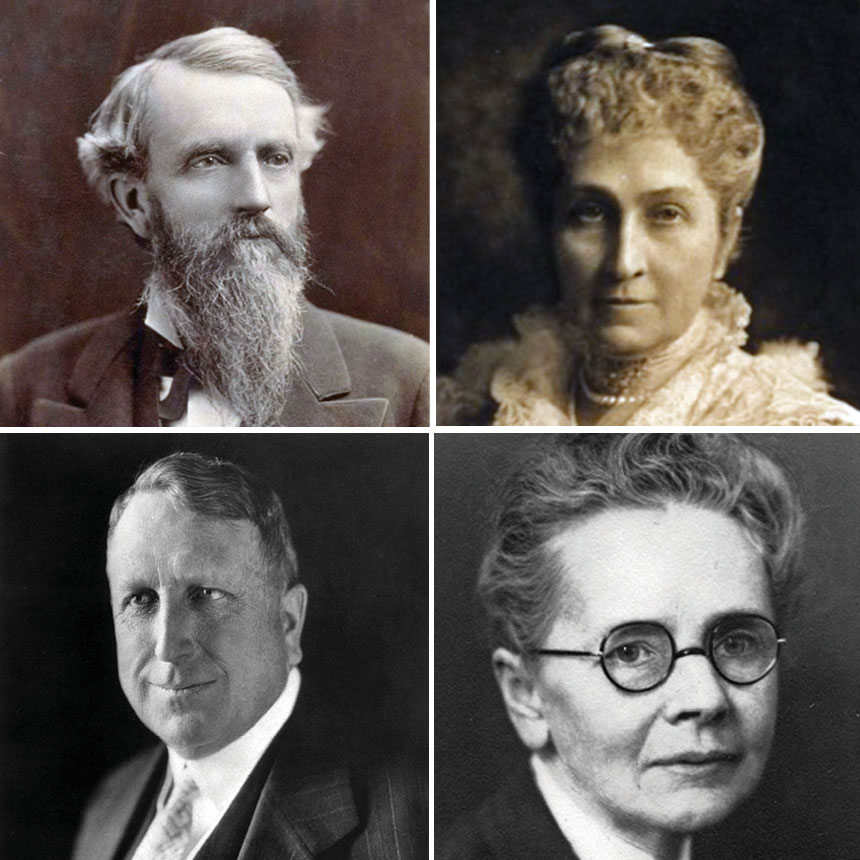

The story of Hearst Castle begins with Hearst’s father, George Hearst. A miner who made a fortune in metals from three of the nation’s largest strikes as well as a businessman and, later in life, a U.S. Senator, George purchased 40,000 acres of ranchland near San Simeon in 1865 when his only child was still a toddler, and the two of them often camped where “W.R.” would eventually build.

“I love this ranch,” Hearst wrote as an adult to his mother, Phoebe. “It is wonderful. I love the sea and I love the mountains and the hollows in the hills and the shady places in the creeks and the fine old oaks and even the hot brush hillsides — full of quail — and the canyons — full of deer. It is a wonderful place. I would rather spend a month at the ranch than any place in the world.”

Although George hoped his son would join him in the mining business, Hearst begged his father to give him control of a newspaper the elder Hearst had won gambling. It was the start of the younger Hearst’s own empire. Soon after taking control of the San Francisco Examiner, Hearst purchased his second newspaper, the New York Journal.

During his lifetime, Hearst accumulated more than two dozen newspapers, launched a magazine, and acquired others, including Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping. He added radio stations to his media portfolio and started a movie studio as well as a book publishing division. Wealthy in his own right, William Randolph Hearst inspired Orson Welles’s 1941 classic Citizen Kane.

But Hearst struggled to manage his money, according to O’Brien. He didn’t understand the concept of a budget and borrowed money to pay off or refinance his debt, so despite his wealth, he couldn’t afford to build a massive estate on his own. He needed his father’s funds.

When George died in 1891, he left his fortune to his wife Phoebe, Hearst’s mother. Victoria Kastner, a former historian at Hearst Castle and author of Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect, says Phoebe unknowingly played a role in the construction of Hearst Castle by paving the way for him to meet Julia Morgan, the woman who became the architect behind Hearst Castle.

In a presentation to the Hearst Castle Preservation Foundation, Kastner shared how Phoebe funded the first international architecture competition in history in 1896. The prize was a commission to design several buildings on the University of California’s Berkeley campus.

It’s unclear when Phoebe met Morgan, who had studied civil engineering at Berkeley before becoming the first woman to graduate from the architecture school of the acclaimed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. However, the winner of Phoebe’s competition, Émile Bénard, declined to be appointed the supervising architect, so John Galen Howard (who had originally placed fourth) was awarded the position, and he appointed Morgan the construction superintendent of the Greek theater. That role could have put her in contact with not only Phoebe but William Randolph Hearst himself, since he donated money for the theater and attended its grand opening.

Regardless of when they met, Kastner says, Morgan became the “architect royal of the Hearst family” after starting her own firm in 1904. One of her first residential commissions was to complete Hacienda del Pozo de Verona after the architect of record died, a project that in some ways foreshadowed Hearst Castle.

As Kastner explains, Hearst had asked his mother if he could build a house on another family ranch in Pleasanton, California. Phoebe agreed, but knowing her son’s trouble with money, cautioned him to keep the project under control. Hearst couldn’t rein himself in. By the time Phoebe visited Hacienda del Pozo de Verona, the home already had more than 50 rooms. Furious, she confiscated it.

Undaunted, Hearst continued to turn his attention elsewhere. He had continued to camp out at the San Simeon ranch, bringing his five sons to the same place he had stayed with his father. They slept in tents, but Hearst wanted more permanent accommodations at “Camp Hill.” After what had happened with Hacienda del Pozo de Verona, Phoebe understandably opposed this project.

Then, in 1919, Phoebe died from Spanish flu. With no one to hold him back, Hearst wrote to Morgan: “Miss Morgan, we are tired of camping out in the open at the ranch in San Simeon and I would like to build a little something.”

Walter Steilberg, a draftsman in Morgan’s office when she met with Hearst to discuss his hilltop estate, revealed in later interviews that the media mogul initially asked for a simple three-bedroom, two-bathroom ranch-style home. But the plan quickly evolved. Drawing inspiration from the European tour he had taken with Phoebe as a ten-year-old, Hearst asked Morgan to design a Spanish Renaissance village overlooking the ranch, which by then had expanded to 250,000 acres.

Hearst envisioned, at the top of the hill, a main house that looked like the cathedrals he had seen in Spain. Walkways would ribbon from the house, through elaborate Italian and Spanish gardens and to the three surrounding cottages, where he could house guests. Additionally, he had plans to showcase his fine art collection. Hearst broke ground on what he called La Cuesta Encantada — The Enchanted Hill — in the fall of 1919.

Kay Brynildson, a tour guide at Hearst Castle, says Morgan immediately put her civil engineering degree to use. Since the family rode horses to Camp Hill, she started with a road, followed by a hydroelectric plant to get water to the site. As work progressed, she tackled the sewer, electrical, and plumbing systems. Later, she designed not only the buildings but also the project’s gardens and interiors.

“Julia was involved in absolutely every aspect, as was W.R.,” says Kastner, adding that they were constantly discussing the estate.

Steilberg recalled that when the two of them bent over a drawing board, everyone else could have been a hundred miles away, and he swore he could see creative sparks fly from one forehead to the other. On weekends when Morgan stayed at the estate, Hearst always had her sit next to him at dinner so they could continue their conversation.

Their like-mindedness didn’t mean Morgan always agreed with Hearst, though. “She didn’t say no, but she talked him out of things,” Brynildson explains. “She was diplomatic. They would have heated discussions, but they never raised their voices, never argued.”

During the 28 years they worked together on Hearst Castle, the two had plenty of opportunities to argue. For starters, Hearst owned only 5 percent of the current art collection before 1919, and he was constantly buying pieces he wanted to display at the estate.

“Objects are coming in, and they are never the right size, and they have to be incorporated into the structure,” Kastner says. For example, the ceiling in the refectory arrived as a row of 16th-century Italian wall panels that had to be assembled into a rectangular shape and then extended with additional pieces to fit the 72-foot ceiling. The choir stalls along the refectory walls had to be similarly extended, and the fireplace in the room was originally only 11 feet tall. Morgan used concrete to give it more height.

Additionally, Hearst suffered from what Morgan wrote was a “severe case of changeableness of mind.” He had the outdoor Neptune Pool redesigned twice after it was initially installed, and he ordered the roof of Casa Grande raised twice. Walkways were widened; gardens were redesigned. According to Brynildson, one of Hearst’s sons claimed that if Hearst had lived twice as long, his estate would have been twice as large and still unfinished.

In 1937, Hearst’s poor money management skills caught up with him. He was forced to relinquish control over his Hearst Corporation stocks and sell personal assets, including his castle in Wales and a portion of his art collection. He also had to suspend work at Hearst Castle.

But as his fortunes rebounded, work resumed until 1947, when the 84-year-old left to be closer to the medical care he needed. Recognizing La Cuesta Encantada’s architectural, cultural, and historic significance, Hearst offered the estate to the University of California, but the university felt it couldn’t afford to maintain the property. The state of California then stepped in.

In 1954, three years after Hearst’s death, California agreed to manage La Cuesta Encantada as a state park and granted a land easement to protect the 82,000 acres that remain of the original range. The newly renamed Hearst San Simeon State Historical Monument began offering public tours four years later.

Today, visitors can see the highlights on the Grand Rooms Tour, go behind the scenes on the Cottages and Kitchen Tour, and learn more about Morgan, California’s first female licensed architect, on the Julia Morgan Tour. O’Brien recommends taking the Upstairs Suites Tour to see the Gothic Suite, her favorite room because it’s where Hearst wrote his daily column under an ornate ceiling Morgan designed just for him.

“I think when we’re looking at his castle, we’re seeing his whole life story,” O’Brien says. “We see his love of camping here, his appreciation for the architecture and art he saw when he went to Europe with his mom, and his entertaining. The man is not separate from the place.”

Teresa Bitler is an award-winning travel writer whose work has appeared in National Geographic Traveler, TripSavvy.com, USA Today’s 10 Best, Wine Enthusiast, AAA publications, and others.

This article is featured in the September/October 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is an amazing article. I have been fascinated by Hurst Castle tge first time I saw it from the road some 50 years ago. My live for art and architecture fueled that interest. I have yet to take the

tour although it’s on my ‘bucket list’! Thank you for this very comprehensive piece.

Unbelievably wonderful. I read the above in the current issue, but also the in-depth 1959 feature yesterday per the link. I’ve got to do my homework on getting up there and seeing it for myself. With inflation being what it is, every detail has to be examined carefully. The train for sure. There’s so much beautiful scenery along the California coast.