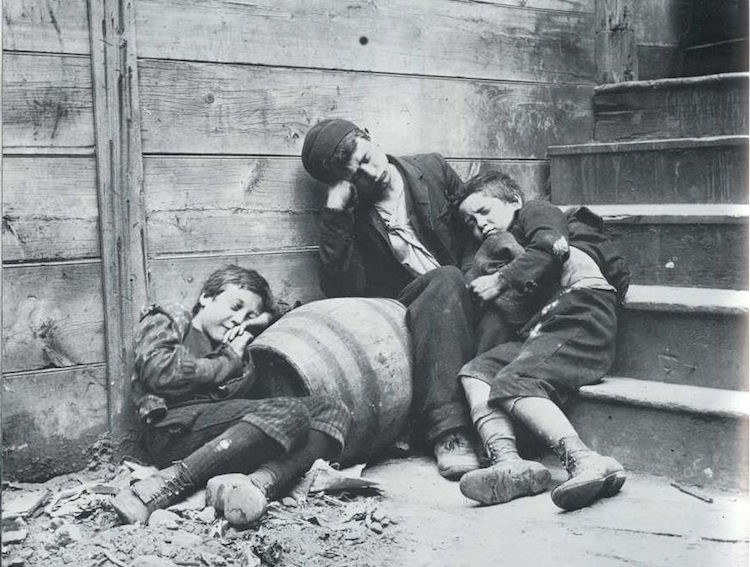

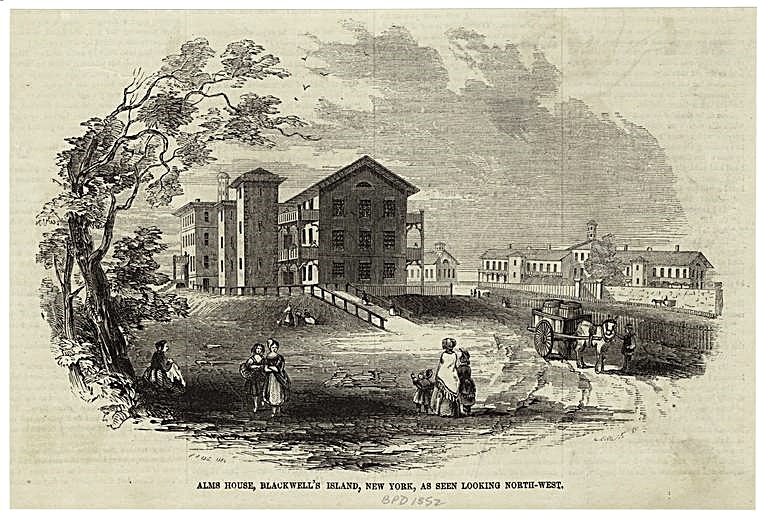

In the 1850s, thousands of homeless children roamed the streets of New York City, many of them sleeping on grates or under stairwells in and around a notorious slum called Five Points. Violent gangs fought over turf in this neighborhood, which was known to have the highest murder rate of any slum in the world, and children were forced to steal, beg, or do dangerous jobs to survive. Minors were routinely thrown into decrepit almshouses or prisons with adults. Institutionalized spaces for children were bursting at the seams, and orphanages, which were chronically short of food, opted for harsh discipline and rigid rules rather than individual care.

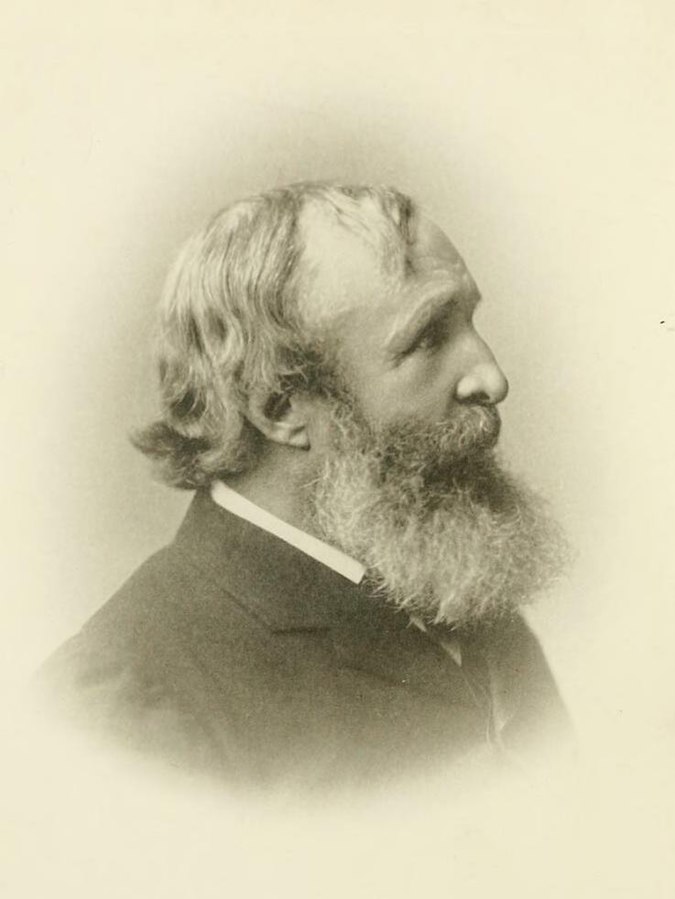

The conditions deeply disturbed a young seminarian named Charles Loring Brace, who decided to channel his devotion to his faith into efforts to change the lives of these children. In 1853, at age 27, Brace founded the Children’s Aid Society (CAS), establishing a revolutionary model for child protection that continues to serve as the country’s foundation for our child welfare system.

Born in 1826 in Litchfield, Connecticut, Brace was the second oldest of four children in a family steeped in progressive political activism. Ministers, abolitionists, judges, and lawyers dotted his family tree. His father, John, was a history professor at an all-girls school and a believer in women’s equality. He taught Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who thought so highly of her beloved teacher, she named a character in one of her novels after him.

Brace attended Yale Divinity School, graduating as a top student, then moved to New York City to attend Union Theological Seminary. To support himself, Brace taught Latin and wrote articles with moral and religious themes for several publications, including the New York Daily Times. He loved exploring the city with Frederick Law Olmsted, who later co-designed Central Park.

Union Theological was a short walk to the Five Points slum district as well as other neighborhoods known for abject poverty, and Brace was appalled at the misery he witnessed when conducting in-home visits or ministering to the sick as part of his seminary training. He had a special concern for the thousands of vulnerable children — up to 40,000, according to Miriam Z. Langsam’s book, Children West — he saw trying to survive in the worst of circumstances.

On a trip to Europe, Brace studied other methods for supporting and uplifting people in crisis and was especially struck by a German orphanage that provided a home environment with a theological student as a house parent. The children had time for play as well as chores, and the ones who were employed were required to give small amounts of any income as payment for their care.

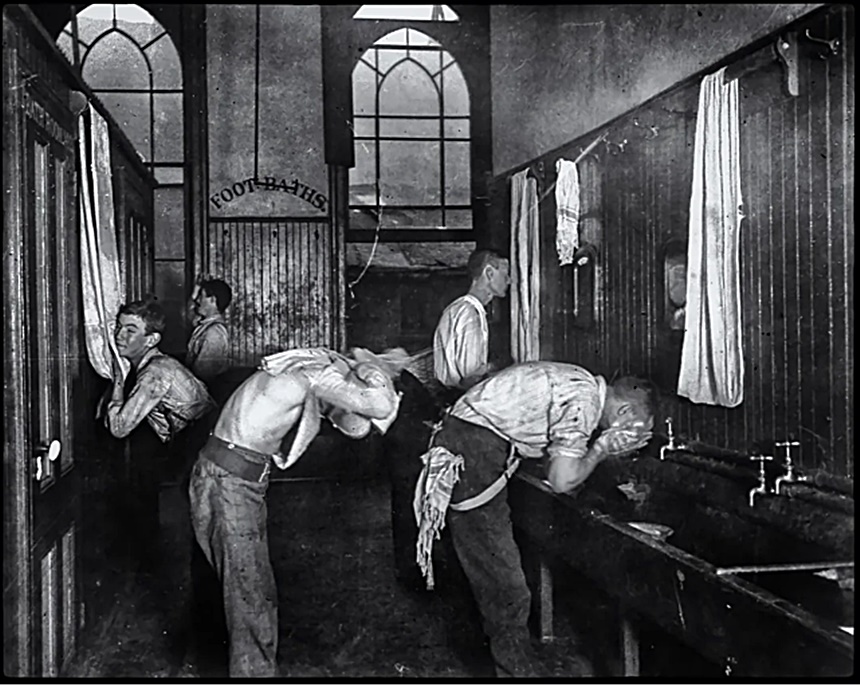

When he graduated from seminary, Brace decided to focus on helping children rather than seeking a full-time job as a preacher. He started with Sunday schools, educational programs, and lodgings for boys and girls. In 1854, Brace opened the nation’s first runaway shelter, the Newsboys’ Lodging House, which offered decent food, shelter, and hygiene as well as job training and basic education. The lodgers were responsible for daily chores, and Brace required them to pay a small amount for the services they were receiving, convinced a hand-up rather than a hand-out produced a more productive individual.

“By the time Brace turned 30, he would already be the preeminent figure in American child welfare, a status he would enjoy the rest of his life,” according to Stephen O’Connor in his book Orphan Trains: The Story of Charles Loring Brace and the Children He Saved and Failed. “The CAS was in many ways a revolutionary and truly beneficial organization,” O’Connor writes.

However, Brace became increasingly aware that he couldn’t pay enough employees or build enough group homes to care for all the vulnerable and needy children of New York City. So, he began hatching plans to send them out of the city into towns and homes where he believed they had greater odds of thriving.

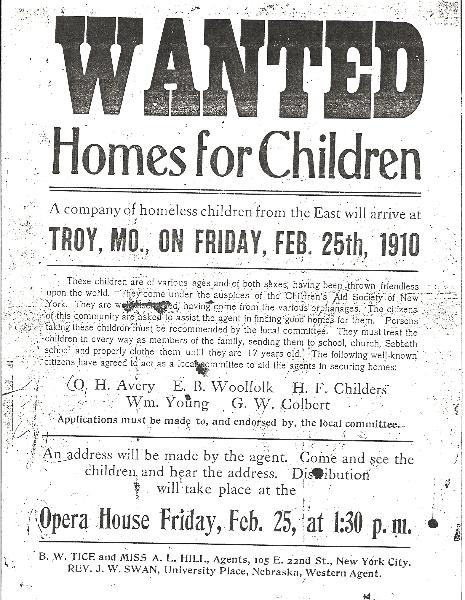

His social experiment, known as the Emigration Plan and now typically called the Orphan Train, began in 1854 and endured for 75 years. An estimated 250,000 children (the exact number is unknown) were routed to families outside of New York City in hopes that they could provide a better life for the destitute youngsters. Although Brace initially tried to keep the children close to New York City, he eventually came to believe that other states — particularly the Midwest — held the most promise for the children.

The first train was sent to Michigan in 1854 with 45 children of varying ages who were resettled with local families. Soon Brace was orchestrating a steady exodus of children from New York City.

An adult representing CAS would accompany small groups of children of all ages on two- to five-day voyages by boat or train or both. Local facilitators would advertise the children’s arrival in towns across the country, vet applications from families or employers, and try to find good matches for the children. The arrangements did not usually lead to formal adoptions — in fact, many states had no laws governing adoption in the early days of the program.

CAS expected anyone who claimed children to feed and clothe them, send them to school, give them work or chores, and treat them like one of the family. However, the “contract” (no one was required to sign anything) between child and “employer” or “family” was loose and could be terminated by either party.

Brace’s Emigration Plan was deemed a stunning success at the time and even given credit for a decline in crime in New York City. Many of the children thrived in their new homes, and a few went on to great success in life. Two became governors and another became a Supreme Court Justice. Orphan Train scholar O’Connor explains that Brace’s plan “may have succeeded as well as could reasonably be expected.”

But as popular as the movement was in its day, the Orphan Train today is viewed much more skeptically, and its shortcomings may be better known than its successes. Children who were placed in families were supposed to be monitored by regional and local agents, but such oversight was difficult or nonexistent. The screening of potential parents or employers was shockingly primitive, and accounts of abused children and separated siblings make it clear that some children ended up in worse situations than the ones they were “rescued” from.

The idea of an Orphan Train can be an appalling concept to modern sensibilities. But in an era when child labor was normal and even necessary for many families, and indentured servitude was an accepted form of learning a trade, sending children out of the slums of the city into the arms of total strangers in the country seemed like a plausible, even preferred, solution. Few people at the time ever considered the needs of an individual child, so it was not seen as unusual or cruel to apply a uniform solution to child welfare, especially to those who were stigmatized as orphans or poor.

Brace had no training in what we would today call “child psychology.” But he despised institutionalized care and believed giving children a chance to work on a farm, experience family bonds, and learn Christian values would give them a better chance at a successful life than they could get on the streets of New York City.

Brace and the CAS also advocated for children in many ways beyond the Orphan Train. He successfully fought for laws limiting the hours children could work in factories and preventing them from being committed to county almshouses. The CAS also established a summer home for girls in Brooklyn, a sanitarium for sick babies in Coney Island, and its own probation department upon the founding of the first juvenile court.

The Children’s Aid Society is still going strong today as one of the oldest nonprofit organizations in America. Highly respected among child welfare organizations, the CAS remains committed to improving the country’s foster care and adoption processes, many of which can be traced directly to the efforts of Brace, who died in 1890.

While he is best remembered for his Orphan Train, Brace’s lasting legacies include the Children’s Aid Society and his status as the father of the modern foster care movement. There are an estimated three million people currently living who are direct descendants from those who rode the Orphan Train from 1854-1929.

Charles Loring Brace endeavored to find alternative solutions within an archaic, broken, and ineffectual system. Sadly, many social ills the CAS and Brace confronted are remarkably similar to what is still faced today. In her 2020 book, New York’s Newsboys: Charles Loring Brace and the Founding of the Children’s Aid Society, Karen M. Staller writes, “For today’s social justice advocates, who may be discouraged by the grand challenges they face, Brace’s life and the work of the CAS offer a fresh stimulus for inspiration, courage, and action.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Charles Loring Brace accomplished an awful lot for only one man without precedent in the United States prior to him. It was really overwhelming, but he studied and worked hard to build the foundation no one else had before; helping kids in crisis have some semblance of normalcy and hope, with Children’s Aid Society and the Orphan Train.

The last paragraph is discouraging that many of the same social problems from Mr. Brace’s time are still with us today, unfortunately. It’s something I feel will always be a problem. Still, things are as good as they are now despite this, because of what he put into place.

It would be wonderful if we had a government that actually cared about its own people, not working against them, having the gall to call themselves ‘leaders’ or ‘public servants’ when they’re there only to steal from us, and lining their own pockets with millions more from the complete corruption of special interest groups and corporations.