In olden days, a glimpse of stocking

Was looked on as something shocking

But now, God knows

Anything goes

–Cole Porter

America is a tough room. You can’t joke about anything anymore.

Or so we’re told. “We’re in this place where everyone’s like, ‘You can’t say this, you can’t say that,’” Whitney Cummings told Matt Wilstein on The Last Laugh podcast. “I think it’s particularly worrying at the moment because you can only create in an atmosphere of freedom, where you’re not checking everything you say critically before you move on,” legendary Monty Python’s Flying Circus member John Cleese told an interviewer.

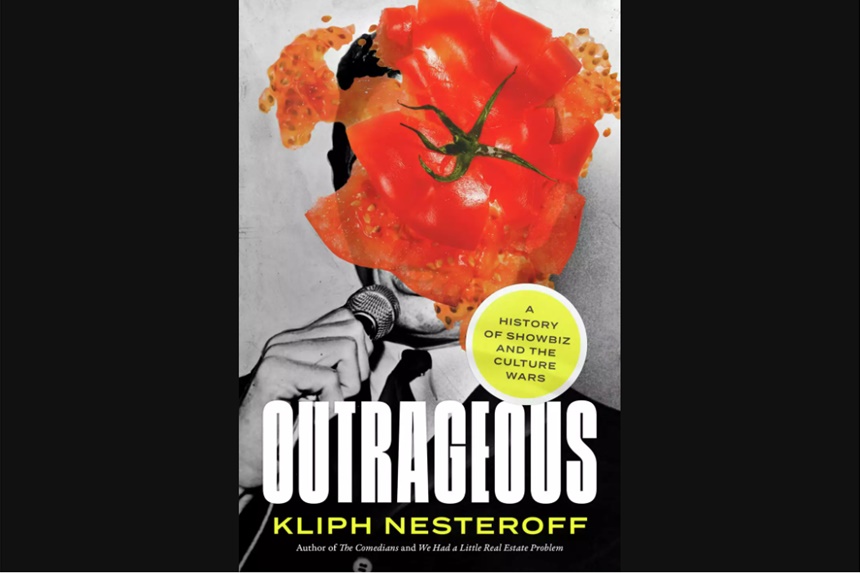

Kliph Nesteroff has heard all this before. As he chronicles in his new book, Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars, the comedy historian and author of the essential book, The Comedians, maintains that America has not suddenly lost its sense of humor. The so-called culture wars have been waged for centuries.

In the colonial era, he writes, the Continental Congress passed a law decreeing the closure of all places of public entertainment. In the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s, dance shows were raided if too much leg was shown. Decades before Will Smith slapped Chris Rock at the Oscars, a female audience member attacked Welsh comedian Ossie Morris after he uttered two profanities. In the 1950s, when Desi Arnaz wanted to work his wife Lucille Ball’s pregnancy into I Love Lucy, sponsor Philip Morris told him, “You cannot show a pregnant woman on television.” (You couldn’t even say the word; the episode itself was titled, “Lucy Is Enceinte.”)

“The idea you that can’t say anything anymore is hyperbolic,” Nesteroff says in a phone interview. “Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, and Richard Pryor were each arrested for the language they used onstage. Mae West went to jail. Today, even if a comedian caused outrage, nobody would be arrested. It’s disrespectful to those who came before and blazed this path when you really couldn’t say certain things.”

As a complement to his book, Nesteroff has recently been posting on X (formerly Twitter) contemporaneous letters to the editor from irate TV viewers who were shocked and offended by what they were seeing in prime time. Like viewer Bernie Splim, who protested the food fight on a 1986 Thanksgiving episode of Cheers: “Couldn’t they have had Sam [Malone] open the bar to feed the homeless?” he complained.

Nesteroff believes that social media is fueling the misperception that we are overly sensitive these days. “In the days before the Internet, people’s reactions to show business was very similar to the reaction we see on social media,” he says. “The difference was if 100 people wrote 100 letters to the editor, only one or two would be published. Today, letters to the editor exist without the editor. They are sent out as tweets or Instagram posts and all 100 are posted. I don’t believe this conceit that people are more sensitive or easily offended today. It’s just now there is no filter. In reality, people were probably much more sensitive in the past because we had far greater taboos when it came to sex, religion, politics, and language.”

Today, at least five of George Carlin’s “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television,” can be heard in prime time. “There is more freedom of speech and freedom of expression today,” Nesteroff maintains. “But we’re being told the opposite.”

For example, Nesteroff points to controversial films in cinema. While D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation advanced cinema as an art form, it also glorifies the Ku Klux Klan. Gone With the Wind may be one of the most honored and beloved films of all time, yet it presents a benign view of the antebellum South. But as Nesteroff writes, America did not just suddenly get more sensitive toward these controversial films (HBO Max temporarily pulled Wind in 2020). They were banned or protested at the time of release in 1915 and 1939, respectively.

Outrageous is not officially dedicated to comedian Gilbert Gottfried, who died last April, but some stories in the book were absolutely included with Gottfried in heart and mind, Nesteroff says. For instance, Nesteroff writes in Outrageous about game show fans being “repulsed” by Family Feud host Richard Dawson’s penchant for kissing female contestants on the mouth. In response, the show instituted a policy by which male and female contestants had to undergo a mouth test for herpes and other diseases.

“Part of including that is the spirit of Gilbert Gottfried and what would make him laugh or make his jaw drop on the floor,” Nesteroff says. “The Richard Dawson herpes test is one I never got to share with him. I guarantee that if he were alive, I would lead with that on my next podcast appearance.” (Nesteroff was a popular guest on Gilbert Gottfried’s Amazing Colossal Podcast, which was devoted to old school show business with eager digressions into entertainers behaving badly.)

Gottfried himself had “multiple controversies” throughout his career, Nesteroff says, “and I wanted to have at least one Gilbert story in the book.” That story is Gottfried’s 1991, well, outrageous, appearance on the Emmy Awards, which coincided with Paul Reubens’ arrest in an adult movie theater (in comedy, timing is everything). “Gilbert was supposed to read material off the teleprompter, but he went rogue and did a series of jokes about masturbation,” Nesteroff says. “He got huge laughs, but the show’s writers said they were disgusted by his performance. Michael Medved singled out Gilbert as an example of what he called Hollywood’s contempt for middle America.”

That seems to be a recurring line of attack in the culture wars: us vs. them. Perhaps one of the key lines in Outrageous is Nesteroff’s observation that “While the showbiz of a hundred years ago may seem remote, it is remarkable how similar the issues of the past are to the concerns of today.” For example, there’s this quote: “We must take our country back…cleaning up what I think is the dismal swamp, draining that swamp.” Donald Trump in 2016? No, presidential candidate Pat Buchanan in 2000.

The culture wars rage on. Nesteroff hopes people can chill out a bit. “I do not care for these doomsday prophecies that the world is coming to an end,” he says. “People used to say this in reference to the tango, the jitterbug, rock and roll, and comic books. You hear the same thing today when people refer to drag queen story time, The 1619 Project, or a comedian making a joke you don’t like. Every generation thinks that everything happening in their day is unprecedented. You feel the hysteria that is sent to us intentionally and unintentionally on the Internet. But controversies quickly dissipate as the years pass. We’re still here.”

Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars is now available from Bookshop and other retailers.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you for this feature, which gives us all a lot to think about. One actually is a distortion of time from so much going on as mentioned here. When both Gilbert Gottfried and Paul Reubens were mentioned above, I did a brief double-take mentally, thinking at first both had been gone a couple of years, when in fact its only been 8 and 4 months respectively.

Gilbert’s jokes at Paul’s expense in 1991 were mean. Paul would never have done that to Gilbert if the situation had been the reverse. Anyway, what’s done is done on that. No one’s perfect, and most of us deserve second chances. Today there seems to be the accurate, overriding feeling both political parties are working blatantly against the average American in an aggressive, in-your-face manner, knowing we can’t do anything about it.

Indeed, none of them ever identify as ‘American’. Always hiding behind ‘Democrat’ and ‘Republican’. The only time American is used, is in referring to ‘The American People’ as their way of separating themselves from us, they never deviate from. Bellowing from a large Orwellian screen, like the entertainment industry. The latter though, is where ‘we the people’ do have control over their fortunes, and we see where that’s going, and has been for a long time. The auto industry too. All the $80k+ SUV and truck ads to buy (on credit naturally) for the Holidays like they’re penny candy. The ‘Outrageous’ book is a far better choice from the Post’s site, not Amazon.