When critics examine the history of cinema, one decade that’s often cited as a high-water mark for film is the 1970s. Reasons for run the gamut from a greater emphasis on director autonomy to being the last years before the major studios were gobbled up by large corporate parents. Fifty years ago, December of 1973 saw the release of a number of classic films that both expressed and refuted notions about the decade.

December 5: Serpico

Serpico trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Studiocanal Cinema Club)

Director Sidney Lumet straddled the old studio system and the so-called “New Hollywood,” which saw directors take on a more prominent creative role with wildly divergent signature styles. Lumet had directed the all-time great 12 Angry Men and became increasingly known for gritty style that questioned the system (well, any system) in America. That eye for social justice was on display in Serpico; the screenplay by Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler was based on the book of the same name by Peter Maas (with Frank Serpico). Serpico was a real-life NYPD officer who tried to out corruption in the police department and survived being shot in a botched raid; Serpico’s whistleblowing was part of the impetus for the Knapp Commission, which investigated that corruption from 1970 to 1972. Lumet cast Al Pacino as Serpico and painted an unvarnished picture of systemic corruption. The film was nominated for a number of awards, including two Oscars, and secured a Best Actor Golden Globe for Pacino and a Writers Guild of America Best Adapted Screenplay Award for Salt and Wexler.

December 11: The Three Musketeers

The Three Musketeers trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers)

Richard Lester had already deployed music and comedy in TV and film projects before he landed in the director’s chair for both The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965). He would transfer that light touch to a rollicking, swashbuckling take on Alexander Dumas’s classic, The Three Musketeers. A U.S. and U.K. co-production that hewed closer to traditional studio tendencies, the star-studded film featured Michael York, Oliver Reed, Richard Chamberlain, Frank Finlay, Charlton Heston, Christopher Lee, Faye Dunaway, and Raquel Welch (who won a Golden Globe for her performance). A well-received hit notable for both comedy and action, the film unintentionally triggered new protection for actor’s contracts. Producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind had originally envisioned the film as a three-hour-plus epic, but decided midway to break the film into two installments. However, the cast was not informed until the first film was completed. Litigation ensued, as the actors were contracted for one film, not a pair. Since then, the Screen Actors Guild has insisted on contractual language that prevents single productions from being broken into multiple films without prior consent. The follow-up, 1974’s The Four Musketeers, also did well. Interestingly, Lester and a large segment of the cast (including York, Reed, Chamberlain, Finlay, and Lee) would reconvene in 1989 for The Return of the Musketeers, based on Dumas’s own sequel, Twenty Years After. One supposes that a sequel based on a sequel is about as Hollywood as you can get.

December 17: Sleeper

Sleeper trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Woody Allen)

Directed, written by, and starring (the, admittedly, very problematic) Woody Allen Sleeper was a hit and immediately embraced by critics as a comedy classic. It was a departure for Allen in that he employed dystopian science fiction in the commission of his usual brand of witty satire; many scenes also indulge in a more slapstick comedic style than other Allen works. Though Sleeper was a major studio film (United Artists), it did subscribe to the auteur theory that was popular in the decade; as writer, director, and star, Allen wielded a tremendous amount of creative control, essentially guaranteeing that the film was his vision. The film marked the second time Diane Keaton and Allen worked together (they had co-starred in Play It Again, Sam, which he did not direct); the pair made six further films together.

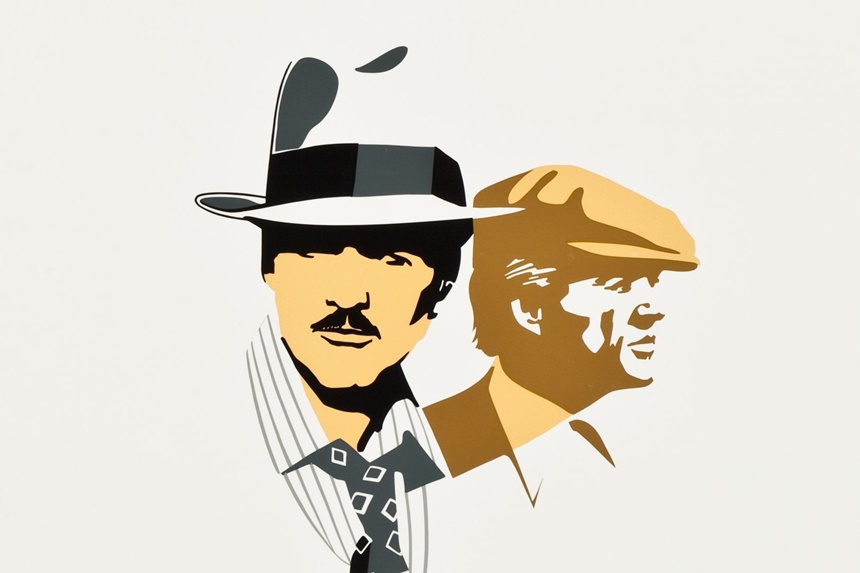

December 25: The Sting

The Sting trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers)

In one way, The Sting could have been seen as “typical” Hollywood fare. However, director George Roy Hill already had a certified classic in the bank with Paul Newman and Robert Redford: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. And writer David S. Ward presented a twisty, turny, con game script that has been praised as one of the greatest screenplays ever written. The film was designed as pure entertainment, as the unfolding cons within cons and ultimate surprise ending kept audiences second-guessing and doubting their own eyes. The movie was a massive hit, making almost 30 times its budget, and won seven Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Editing. Marvin Hamlisch’s version of Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer” that was played throughout even became a Top Ten hit. In many ways, despite its lavish design and big name leads, The Sting put a premium on plot and character, allowing it to exist comfortably in that ’70s aesthetic even as it packed theaters.

December 25: Magnum Force

Magnum Force trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers)

As an actor/director, Clint Eastwood frequently works with the same people. Eastwood worked with director Don Siegel on five films, including 1971’s violent action thriller and massive hit, Dirty Harry. For its first sequel, Magnum Force, Eastwood re-teamed with Ted Post, who had directed Eastwood on television in Rawhide and on film in Hang ’Em High. The first Dirty Harry movie opened a new subgenre of maverick cops clashing with their superiors to get the job done by any means necessary. Interestingly, the second film subverted that by pitting detective “Dirty” Harry Callahan (Eastwood) against a gang of young cops acting as vigilantes. The quartet of antagonists were played by Kip Niven, Tim Matheson, Robert Urich, and a pre-Starsky and Hutch David Soul. The screenplay came from Michael Cimino, director of The Deer Hunter, and John Milius, already established from The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean and Jeremiah Johnson. The box office take of Magnum Force exceeded that of the original, cementing Dirty Harry as the first new major film franchise of the decade, one that would continue through The Enforcer (1976), Sudden Impact (1983), and The Dead Pool (1988).

The films of December 1973 were both emblematic of the “New Hollywood,” but some hinted at the franchise wave that would eventually dominate the business. A pair of cop films, a costume adventure, a buddy comedy, and a satire were nothing new, but creatives were finding new ways to tell old stories and experiencing success as they did it.

Meanwhile, another genre was delivering two massively influential films that same month, and in Part II, we’ll look at the outsized influence that The Wicker Man and The Exorcist had, and continue to have, on horror film.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The opening picture here (for ‘The Sting’) is very unique and would look nice just as it is on any wall, with no words. Generally I’ve only ever seen the well known one in the classic Saturday Evening Post style, which ran throughout the film itself otherwise. The artist really copied Leyendecker perfectly down to the last detail, with the circle and two bars completing the look.

Saw ‘The Sting’ and ‘Sleeper’ over the Christmas vacation; ‘The Three Musketeers’ earlier per the release date. Films didn’t stay in the theaters that long in those days either, but for different reasons than now. ‘Serpico’ I saw years later. Al Pacino always delivered great, varied performances.

I never saw ‘Magnum Force’ because I’d seen ‘Dirty Harry’. The commercials for it were more than enough. Clint’s pretty one-dimensional, which got old early on. Same with De Niro, whom my friends and I (probably others) labeled the same way, but with the added ‘poor man’s Al Pacino’.

Anyway, the height of the Watergate era had some excellent films set between the ’20s and the ’40s with ‘The Sting’, ‘The Great Gatsby’ and ‘Chinatown’. But New Hollywood would end permanently in ’76 with ‘Network’ and ‘All the President’s Men’.