On the surface, the windswept mountains, frigid alpine lakes, and lodgepole pines of the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests in Colorado’s southern Rocky Mountains shelter only prairie dogs, pint-sized pikas, and the occasional moose.

But this scenic and remote landscape an hour northwest of Denver is listed as one of Colorado’s most endangered and historic places. Hints to its intriguing past in shaping American history can be found everywhere if one knows where to walk.

The high alpine region of Rollins Pass, a saddle across the Continental Divide, has served as a “great gate” of human and animal migration for millennia. The land is sacred to the Ute and Arapaho tribes and home to 12,000-year-old Paleoindian hunting grounds and trails. As settlers pushed westward in the 19th century, the pass became a popular if short-lived horse and wagon and then railway route.

Signs of recent and ancient human activity are small but evident in this wild backcountry range, and raise questions about who has traveled this way before, and why.

I’ve found myself in this stunning Rocky Mountain landscape, shouldering a large 30-pound backpack filled with dehydrated food, camping supplies, and Leave No Trace gear, as part of Fjällräven Classic USA.

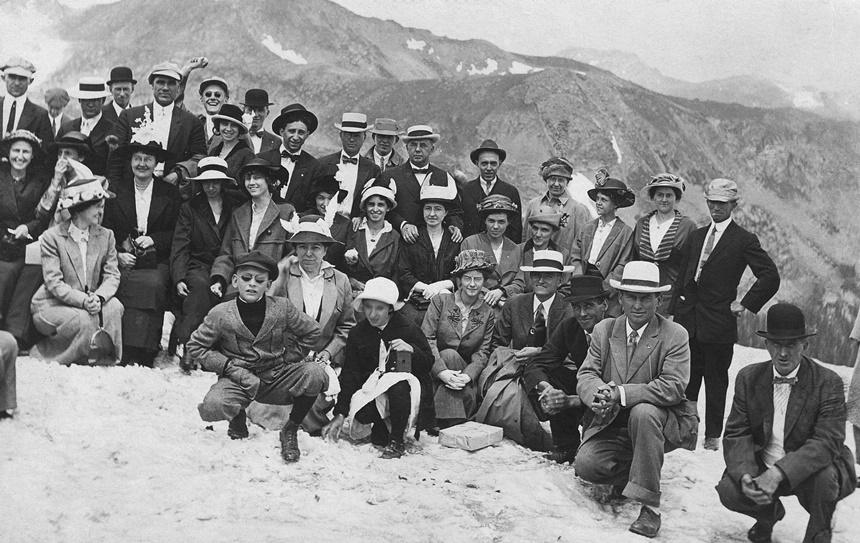

Held every July under special permit from the USDA Forest Service, the Classic USA trek invites hikers to enjoy the out-and-back 30-mile trek over three days of supported hiking and camping through the spectacular James Peak and Indian Peaks Wilderness areas. We’re retracing the footsteps of Paleoindians, Native Americans, settler pioneers, and even early alpine tourists across Rollins Pass.

The rugged uphill route to the pass summit of 11,768 feet winds through dry pine forest before breaking through the tree line to reveal wide mountain vistas with patches of snow clinging to mountainsides in defiance of the July heat. Less obvious features are occasional sightings of thousand-year-old Native American hunting structures. The miles of rock walls and hunting blinds were strategically placed by the indigenous peoples to prey on migrating animals like elk and bighorn sheep.

B. Travis Wright is a co-founder of Preserve Rollins Pass. A resident of Colorado, Wright is a passionate historian who’s spent decades working with Native American tribes, government officials, and archaeologists to promote preservation and education about the Rollins Pass area.

Wright notes that across the state, there are at least 96 Native American alpine hunting sites above 9,800 feet/3,000 meters, with 71 percent found along the Front Range, where Rollins Pass is located. Wright’s colleague, archaeologist Dr. Jason LaBelle, describes these as “one of the greatest concentrations of ancient hunting structures documented in North America.”

I hike past the remains of a stone hunting blind above the shuttered Needle’s Eye Railway Tunnel, pausing to imagine the patience and fortitude of hunters waiting to capture their next meal, and centuries later, settlers winding their way up the rough and rutted wagon road.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Rollins Pass route marked an early pathway into the west for American settlers in the 19th century. First known as Boulder Pass, wagon and railway entrepreneurs saw what became known officially as Rollins Pass as one of the easier crossings over the formidable Rocky Mountains.

Pioneer John Quincy Adams Rollins constructed a toll wagon road here in 1873, three years before Colorado’s statehood. Thousands of settlers and cattle moved along the rustic wagon trail before Rollins Pass became the highest standard-gauge adhesion (non-cog) railroad grade in North America in the early 1900s.

Popular for a time as a scenic and commercial railway, the complexity of the alpine route and its hazardous weather, particularly heavy snowstorms that could strand trains for days, foretold its decline. The safer, more direct Moffat Tunnel, championed by David Moffat, was opened at lower elevation in 1928 and remains in use today.

In reflecting on the merits of this significant region, Wright told me that today’s visitors to Rollins Pass are part of an enduring human tapestry.

Rollins Pass and its chronicles conveyed to each generation are timeless because at the beating heart of all the stories lives the pioneering spirit of consummate grit and tenacity while daring nature, dreaming big, and never losing sight of the magnificent view. Perhaps that is why this Continental Divide crossing over the Southern Rocky Mountains is so beloved: those who make the journey to bask in the magical beauty of this place and feel their souls restored, in some small way reach across the infinite divide of time to uncover their own pioneering spirit on that timeless ribbon of road.

Thinking of those who’ve gone before grants a new appreciation and gratitude for the opportunity to retrace such historic steps into the West.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now