This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On Monday, June 17, 2024, the Boston Celtics defeated the Dallas Mavericks in Game 5 of the 2024 NBA Finals, securing their record-breaking 18th NBA championship in the process. Cheering on the Celtics together has been a defining tradition for my sons and me for a decade, and getting to sit beside them as the Celtics won the championship is without question one of my favorite parenting moments to date — and a particularly poignant one as it’ll be the last significant sporting event we watch together before my older son begins his first year of college in August.

The Celtics don’t just connect to Railton family memories, though. Across its more than 75 years of history, the team has exemplified some of the best and the worst of professional sports in Boston and America, particularly in the context of race and racism (and often in conversation with the Boston Red Sox).

From the earliest era of professional sports in Boston, one of the city’s foundational teams reflected racial stereotypes. As I highlighted in this Considering History column on the Atlanta Braves, that professional baseball franchise began in Boston — initially as the 1871 Boston Red Stockings, but as of 1912 as the newly renamed Boston Braves, with a Native American mascot and logo to go with the new moniker.

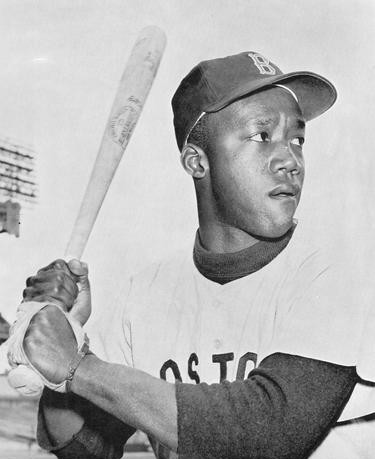

By 1912 Boston was also home to a second professional baseball team, founded in 1901 as the Boston Americans but known as the Boston Red Sox since 1907. The team would come to be associated with a history of racism in both professional sports and the city. The Red Sox were the last Major League Baseball team to integrate, resisting the league’s inclusion of Black players for more than a dozen years after Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Owner Tom Yawkey and other team officials were threatened with a lawsuit (and later sued by another player for discrimination), the NAACP charged the team with “following an anti-Negro policy,” and the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination held public hearings on the team’s racism; the Red Sox didn’t add their first Black player until July 1959.

The Red Sox’s resistance to integration is particularly striking when contrasted with the Celtics, who in their first decades of existence were consistently ahead of the curve when it came to racial inclusion. The team was formed in June 1946 as part of the newly created Basketball Association of America, which in 1949 merged with the longstanding National Basketball League to form the NBA. Just four years after the team’s founding, in the April 1950 draft the Celtics made Duquesne University standout and current Harlem Globetrotter Charles “Chuck” Cooper the NBA’s first drafted Black player. When Celtics owner Walter A. Brown was asked on draft night if he had any qualms about Cooper’s race, Brown famously replied, “I don’t give a damn if he’s striped, plaid, or polka dot. Boston takes Charles Cooper of Duquesne.”

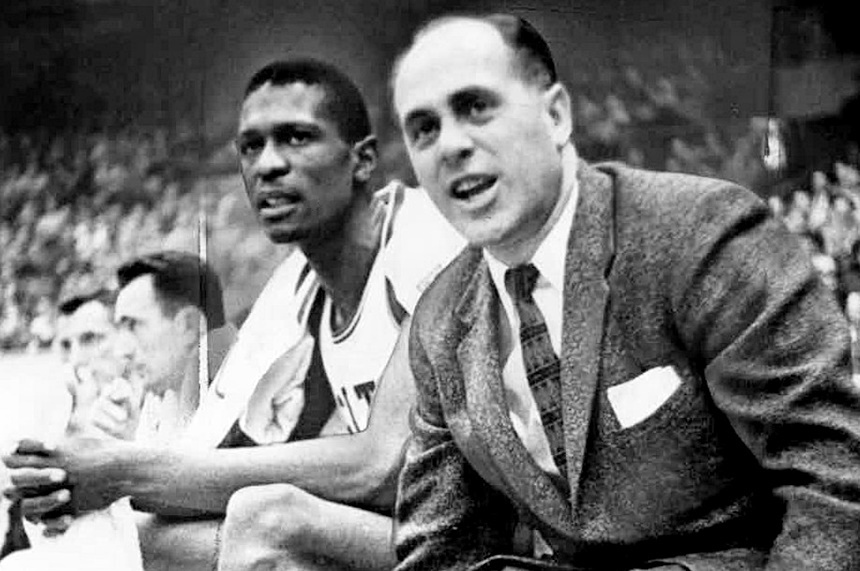

Cooper would play with the Celtics for four years before he was traded to the Milwaukee Hawks, and the Celtics would continue to consistently draft and acquire Black players in an era when they represented a minority of the league. That trend culminated on December 26, 1964, when the Celtics became the first NBA team to feature an all African-American starting lineup; as guard Sam Jones described the moment and the team’s innovative coach, “Red shocked me. I really thought that Red was going to start Havlicek as the fifth man in place of Heinsohn. But Red Auerbach is just different. So there’s five of us, and I said, ‘my gosh, we better win.’” The team did indeed win that game and went on to win the next eleven as well with that groundbreaking starting line-up of Jones, Willie Naulls (starting for the injured Tommy Heinsohn), Satch Sanders, K.C. Jones, and one of the single most dominant and successful NBA players of all time, Hall of Fame center Bill Russell.

Russell’s thirteen seasons with the Celtics produced eleven NBA championships, including a stunning eight in a row between the 1958-59 and 1965-66 seasons. After that 1965-66 season, Auerbach retired as coach (moving fully into the role of general manager), and convinced an initially reluctant Russell to become the team’s player-coach, another innovative idea that made Russell the first African-American coach in any American professional sports league. As Russell noted in his introductory press conference, “I wasn’t offered the job because I am a Negro. I was offered it because Red figured I could do it.” And indeed he could, reaching the Eastern Conference Finals in his first season as player-coach and then winning his final two championships in 1968 and 1969 before retiring on top.

But while Russell consistently dominated the basketball world during his years with the Celtics, his experiences with the city as a Black man were far more frustrating. In August 2020, just two years before he passed away, Russell wrote with precision and passion about those experiences for a SLAM magazine special issue on social justice and basketball. He detailed everyday instances of institutional racism, such as unwarranted police stops; extreme examples of racial terrorism, such as when Russell and his family moved to the predominantly white town of Reading and were greeted with vandalism and racist graffiti; and even racial epithets directed at Russell from Celtics fans, whom he argued “yelled hateful, indecent things” at him during games in his early years with the team. All of these issues led Russell to call Boston a “flea market of racism.”

These painful legacies, as well as the inspiring ones, are present in this 2024 Celtics team. Star Jaylen Brown (who was named the Bill Russell NBA Finals MVP) has talked at length about the systemic racism still present in Boston’s fan culture, but has also worked to create educational, economic, and social justice programs that challenge and transcend institutional prejudice. And head coach Joe Mazzulla, who became the youngest coach since Russell to win an NBA Championship, is the son of a mixed-raced couple; he won the title less than a week after the nation commemorated Loving Day. As we celebrate the triumph of Mazzulla, Brown, and the whole Celtics team, we can also remember these histories of race and professional sports in Boston and America.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now