This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This week, Major League Baseball will celebrate a new season with a controversially delayed Opening Day, with the reigning World Champions the Atlanta Braves hosting the Cincinnati Reds. As a baseball lifer who fell in love with the sport (and really with sports overall) watching the Braves every night on TBS in the early 1980s, the start of a stretch of historically awful seasons for the franchise, typing that sentence should give me a great deal of fan-joy. And it does—but as an American Studies scholar who thinks a lot about race and representation, knowing that a new baseball season will commence with tens of thousands of fellow Braves fans performing a powerfully racist collective chant brings quite a bit of frustration as well.

In a baseball season that will witness the debut of the new name and logo for the Cleveland Guardians (formerly the Indians and the abysmal Chief Wahoo respectively), it’s long past time that the Braves formally revisited and revised their own racist representations, starting with that terrible Tomahawk Chop (a ritual not limited to the Braves, but that’s no excuse). In so doing, they could help us collectively engage with the franchise’s and sport’s histories around race and region, identity and imagery, legacies that include some of the worst but also some of the best of baseball and sport in American culture.

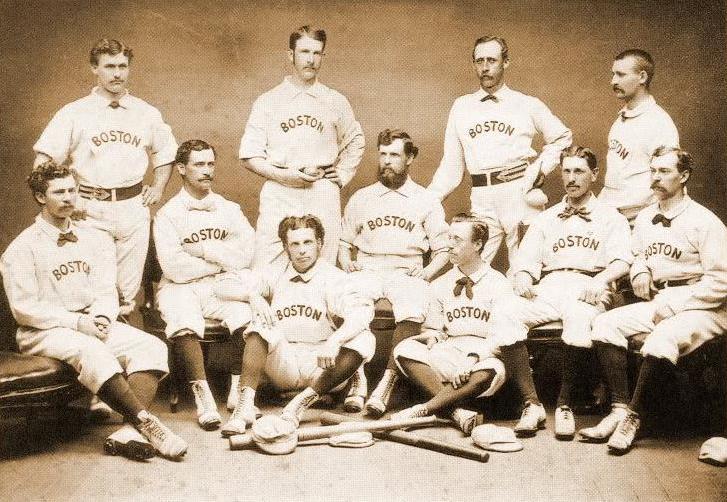

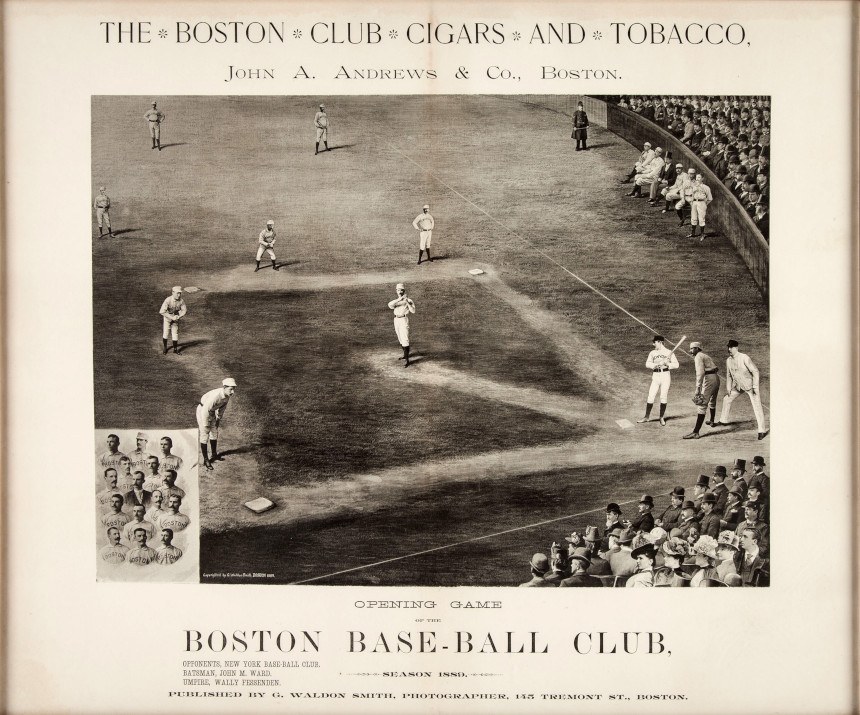

Founded in 1871 as the Boston Red Stockings of the newly created National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP), the franchise is thus not only the oldest continuously operating team in American professional sports—it also reflects baseball’s profoundly local and regional origins and foundations. Many of the sport’s first recorded rules and regulations were set down in 1858 in Dedham, Massachusetts by the Massachusetts Association of Base Ball Players, an organization that formalized the influential early version of baseball known as “The Massachusetts Game” (in contrast, as so much of New England sports have remained ever since, with the incipient New York Rules). Most of the players who joined the Red Stockings, as indeed with many who formed the NAPBBP, came directly out of these Massachusetts games and teams.

Even as the sport became gradually more nationalized and professional over the next half-century, as illustrated by the NAPBBP’s 1871 creation, most of baseball in both New England and throughout the nation continued to be played on that more local and semi-professional level. That created space for not only countless such semi-pro teams and leagues across the region, but for players from a variety of communities and walks of life to take part in this blossoming national pastime. In my current book project, I’m focusing on the story of one particularly unique and inspiring such group of players, about whom I first wrote at length for this column two years ago: the Celestials, the semi-pro team formed by Chinese American students at the Hartford, Connecticut Chinese Educational Mission. Those players, who came out of New England high schools and colleges before forming the Celestials, reflected the local and inclusive nature of 19th century baseball.

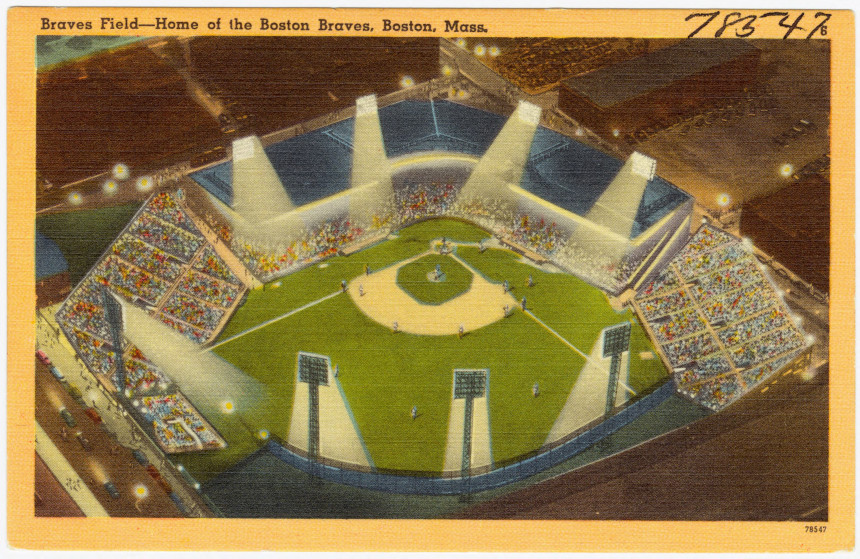

Over the four decades after that 1871 founding, the Red Stockings went through a series of nicknames, with the most consistent and longstanding reflecting those local roots: starting in 1883, they were generally known as the Beaneaters. In the early 20th century a new American League team was founded in the city; known initially as the Boston Americans and then as the Boston Red Sox, this franchise experienced immediate and lasting success, and the less successful National League franchise the Beaneaters would soon lose many of their players to this new rival and struggle to keep a fanbase in the city and region. Something new and different was needed to make the Beaneaters stand out on this increasingly crowded regional and national baseball landscape.

Unfortunately, in 1912 club president John Ward settled on racist stereotypes as the means to draw that renewed attention and fandom. The team had recently been purchased by James E. Gaffney, a New York City construction magnate who was also an alderman in the city’s Tammany Hall political machine. Tammany Hall, which had been named after the Delaware Native American Chief Tammamend, had long used a stereotypical “Indian chief” in full headdress as its emblem. And so Ward decided to honor Gaffney, and in the process to differentiate this New York owner and new franchise direction from its Bostonian roots, by christening the team with a new Tammany-inspired nickname and a stereotypical logo to go with it: the Boston Braves.

Over the subsequent century, the Braves would go through two moves, to Milwaukee in 1953 and then to Atlanta in 1966, but the nickname and (increasingly) stereotypical logos would endure. Indeed, it was during their years in Milwaukee and Atlanta that the franchise truly doubled down on the racist rituals, through the stereotypical mascot known as Chief Noc-a-Homa. Between its 1966 creation and the character’s 1986 retirement, three men played the Chief at home games; the first two were white performers in “redface,” but the third and most enduring was an Ottawa Native American, Levi Walker, who played the role from 1969 to 1986. Walker’s role unquestionably complicates narratives of this character as purely stereotypical, but it doesn’t absolve the team of the consistent and overarching use of stereotyping imagery—not just around the Chief, but with other characters (such as the early 1980’s addition Princess Win-a-Lotta) and rituals (such as the early 1990s use of the Tomahawk Chop, which has endured long past the retirement of these mascots).

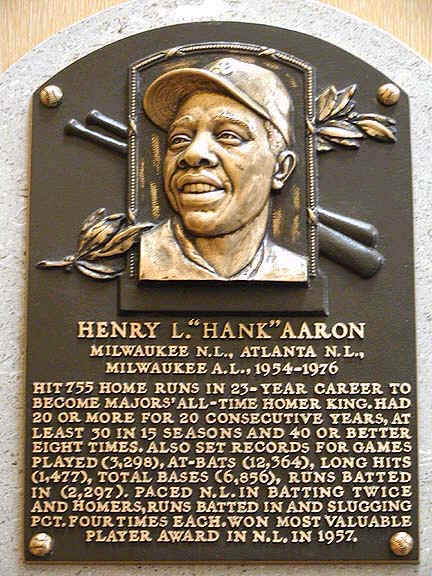

What’s particularly frustrating about the endurance of the Braves nickname and rituals like the Chop is that the franchise’s history also features one of the most iconic social and cultural ambassadors in American sports history: Henry “Hank” Aaron. Aaron, whose playing career spanned the Milwaukee and Atlanta eras, was more than just one of the greatest baseball players of all time. “Hammerin’ Hank” was also a legend who consistently challenged histories of prejudice and racism: from his foundational professional origins in the Negro Leagues and move into a still-integrating early 1950s Major Leagues; through his successful pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record and the racist hate he endured and transcended; and to a long post-playing career as a leader for both the Braves and Major League Baseball in their continued efforts to address issues of racism in and beyond the sport.

Neither the Braves nor baseball, nor any of us, can forget the histories of stereotypes and racism that are part of the franchise and sport, as of every layer of American society. But that doesn’t mean we can’t work to change those images and live up to the legacies of the best of baseball instead. As a new baseball season gets underway in Atlanta, it’s time for the team to become part of those changes, and there’s a perfect new nickname right in front of them: the Atlanta Hammers.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

As a Native American I can say that it is NOT an honor to have these historically racist team nicknames endure throughout history. My high school followed the same pattern of ignorance that thousands of other sports clubs have through history. It is NOT insulting to me that these names are challenged and sometimes changed on behalf of the marginalized people who have been demeaned by them. It is in fact an honor that someone would acknowledge the error.

I criticize the thought, not that people would think that something that has been wrong for so long and that at some point could be made right even if but a little, but that someone would have the audacity to gaslight an entire people that they have somehow been honored by a century of ignorance. That thinking is clearly offensive. There should be an apology for that.

As an aside, back in the 1980s & 1990s, Ted Turner, then Atlanta Braves owner, created something called the Goodwill Games. His TBS was now a “superstation” & broadcast the Braves games across the country. The Braves were called “America’s team!”

But in 1990, TBS broadcast the Goodwill Games from Seattle & hence preempted its Braves games. The Washington Post ran a headline on its sports pages, “America’s Team Now Nobody’s Team!”

Always wondered how the Braves, TBS, & Ted felt about that!

Thanks for your comment, Fran. I stand by everything I’ve written, in my 4+ years of writing this column and everywhere else in my career, and would only ever apologize if I got the facts wrong. I do always see my work as part of a conversation, however, and so I genuinely do appreciate your sharing your thoughts here (infinitely more so than the insulting & irrelevant other comments currently on this column).

I’ll say a couple things in response to your thoughts. First, I certainly agree that we need to provide more opportunities and spaces, at all levels of our society and communities, to hear and learn from Native American voices, figures, artists, organizations, and more. I don’t think that stereotypical mascots are required in order for us to do so, and in fact would say that they are far more of a distraction than anything else. So let’s do away with those and, yes, find more and more ways to hear from all our fellow Americans, in every setting.

Second, another layer to that is that we likewise need to engage far more fully with both the histories and the current events around Native American communities. Here are just a few of the places where I’ve written about those issues, here and elsewhere:

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/standing-rock-and-the-for_b_11865978

https://americanwritersmuseum.org/why-we-should-all-read-zitkala-sa/

https://democracyjournal.org/arguments/whats-in-the-native-american-vote/

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2019/11/considering-history-native-americans-sovereignty-and-the-mashpee-revolt/

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2018/10/considering-history-the-fight-for-native-american-citizenship-and-voting-rights/

Keep reading!

Ben

There was nothing wrong with either baseball team name, the Atlanta Braves or The Cleveland Indians!! It was an honor to Native Americans, and makes me very uncomfortable that these names have been changed. The new names aren’t bad as such if they had been the original names of the teams and not changed to suit current ‘political correctness’ run amok.

I suppose it’s a good thing General Motors’ Pontiac division is now gone or they would be retro-shamed for their logo years ago using Chief Pontiac in their ads and on their cars. I remember Chief Pontiac, with the feathers, and the headdress, and EVERYTHING! He was handsome and strong and a trusted figure any man or woman could trust and feel good about, whether buying a car or not.

We know Native Americans have not been treated with the respect they should, so I feel where they HAVE been has definitely been a good thing. These three examples are something we should still be proud of because they’re wonderful. But all are sadly gone. Further ‘canceling’ of Native American names from baseball teams is excluding them from American mainstream inclusion which is wrong and insulting to them! The opening of the games should include a Native American dance, followed by their singing of The Star Spangled Banner which they have every right to sing and you know I’m right. Don’t worry, it’ll never happen unfortunately.

I want you to apologize to the readers of The Saturday Evening Post that you misjudged what you wrote here as you weren’t thinking properly, and are sorry. I’m sure our Native American readers will especially appreciate it, and be forgiving. I will too, but only AFTER I see your apology here. Start writing!

What a ******* bore. Some nit who wants to lecture us about racism. I loved the unintentional hilarity of his acknowledging that Levi Walker “unquestionably complicates” his thesis.

Hey, Mr Railton, I’m as white as your mother’s Sunday best dining room tablecloth, and I was exhilarated when Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s record. In fact, video of that moment showed up in my YouTube feed yesterday, and I re – lived it with great enjoyment.

Go ahead, Saturday Evening Post, you’ve been dipping your toesies in all of the Wokeness sewage for a couple of years now, at least: keep it up and see what it does in the long run to your profits.

You would tell me that because I’ll be 70 next month, I’m representative of a dying demographic, and you’re right, obviously. But because all of you who produce the SEP appear to come from the same conditioned mindset ( it must be sometimes a relief to be a human bot, someone else has done all of your thinking for you, and you are free to become as intellectually underwrought as a fish ), it would never occur to you that sensibilities cross generations. Sure, there are plenty of white Boomers who have bought into white self – abasement and who cannot not see racism, sexism, copophragism ( The Next Battleground!! ) everywhere they look. This is probably truer in each succeeding generation.

But The Saturday Evening Post needs to understand that there are still millions of people of all ages and backgrounds ( I have two severe, nearly lifelong disabilities, so maybe I should seek to rabblerouse opposition to the mere existence of the SEP because of THE ABLEISM INHERENT IN ITS GIVING SPACE TO AN ARTICLE ABOUT BASEBALL!!!!! ) who can appreciate charming and lovely things without suffering that dreadful twitch to politicize or, worse, to be bitter that someone who has written about one of them has not.

Is it possible that you missed Ted Gioia’s remarkable Atlantic Monthly article about the preference of young people ( about 60%, I think it was ) for music from the 20th century? Clue there, maybe? Even for the clueless?

What’s your next winner, SEP, an article about Lia Thomas as the representative American woman?