In 1949, American tennis player Gertrude “Gussie” Moran caused a public excitement at the Wimbledon Championships. While she was certainly a talented tennis player, the attention she got was due to her dress: a daring ensemble designed by tennis player turned designer Ted Tinling, comprised of sculped bodice with a tight waist and an unusually short skirt.

Although the dress adhered to the strict dress code of an all-white outfit, as well as to norms of femininity, what drew the media attention was the “laced panties” underneath, which were meant to be seen as Moran moved on the court. Dubbed “Gorgeous Gussie” by the British press, Moran made her name in tennis history, less for her athletic achievement, and more for her scandalous appearance that kept her in the limelight long after she was beaten out of the tournament.

Gussie Moran in her shocking skirt at Wimbledon, 1949 (Uploaded to YouTube by British Pathé)

While Gussie and her panties made her “The Glamour Girl of Tennis,” and Tinling — who was an official Wimbledon host — was banned from the event for “bringing vulgarity and sin into tennis,” this was not the first time that a woman’s appearance caused a sensation on the court.

In fact, since women started playing tennis in the 19th century, what they wore was at the center of scandals and attention, much more than how they played.

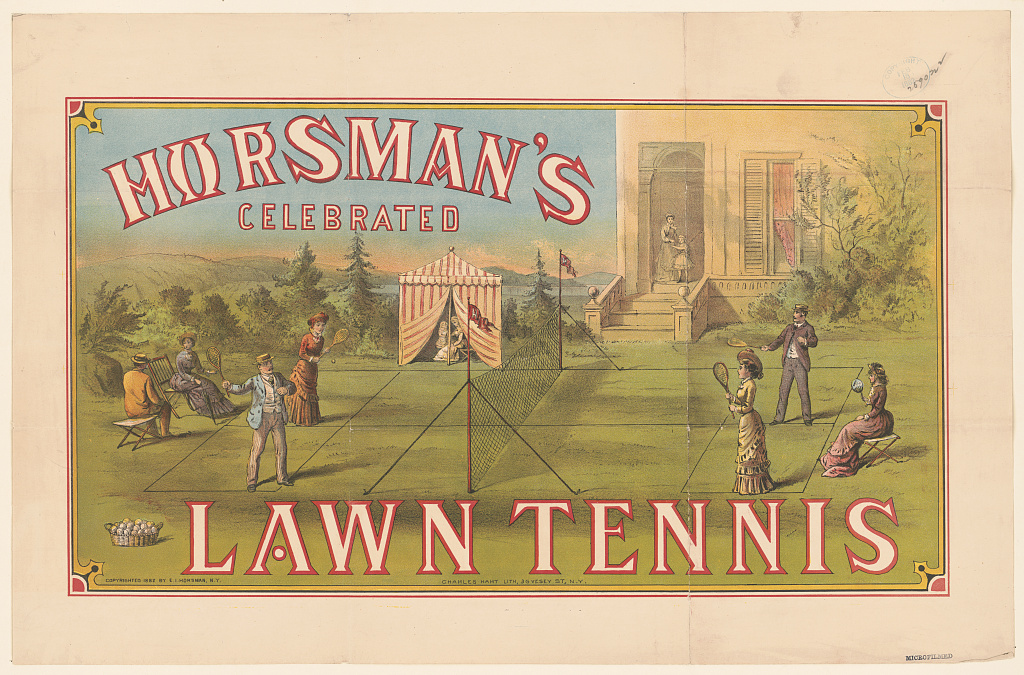

As a sport with a long history and a leisurely and aristocratic image, women’s entrance to the sport was not without hurdles. Yet by the 1870s, women’s colleges began incorporating tennis into their curricula, and playing tennis outdoors became a fashionable recreational activity for the monied elites. As an outdoor, mix-sexed activity however, women were still required to adhere to strict gender norms of femininity and grace. While corsets might have been looser and skirts lacked trains, the appropriate tennis outfit bore resemblance to the contemporary fashions of the day, petticoats and narrow skirts included.

It is perhaps not surprising that the third woman to win at Wimbledon, Charlotte “Lottie” Dod, was able to do it when she was only 15. Considered a child, she was able to have some leniency with regard to her dress, donning shorter and less full skirts that aided her “aggressive” style of fast movement and hard strokes. While her outfit did not grab much attention in 1887, by the time she retired from the sport in 1892 at age 21, she adopted the more restrictive style of her competitors, leaving behind her more fashion rebellious days.

Maintaining femininity on the court was an important facet of the sport well into the late 20th century. But appearing feminine did not necessarily shield women from scandals. When in 1919 Suzanne Lenglen made her Wimbledon debut, her outfit, like Gussie Moran’s 30 years later, was also decried as “indecent” because of its revealing style. Dressed in a V-neck short-sleeved dress with a below-the-knee hemline and without a corset, Lenglen went on to win the championship and to become a fashion icon, popularizing the style for millions of young flappers in the 1920s. Designed by the haute couturier Jean Patou, Lenglen’s outfit was, according to Vogue, the “correct and chic [sport costume] on the court and after the game.”

But if Lenglen and Moran dazzled the public with their brazen outfits, by the 1960s and the rise of the feminist movement, women tennis players began to push against gender norms in more forceful ways, both with their game and their dress.

When Billie Jean King crushed Bobby Riggs in the famous 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” she chose Tinling to design her outfit. After King rejected the first design for being “too scratchy,” they settled on a menthol green, sky-blue short tunic that Tinling embellished with rhinestones. Although King opted for a dress instead of shorts, she made sure to use it as part of her feminist statement. After all, King beat Riggs as a woman, proving her superiority on the court, even while wearing a dress.

King’s victory and subsequent publicity did not put an end to controversies around women in tennis. In 1985, American player Anne White appeared in Wimbledon wearing a full white spandex bodysuit, which drew criticism from the crowd and the press. Thirty-three years later, when Serena Williams wore a similar Nike black catsuit for Roland-Garros, she received a similar reaction. The French Tennis Federation President Bernard Guidicelli called to ban suits on the court, arguing that “one must respect the game and place.”

While both White and Williams viewed the suit as a practical solution to their needs — White wanted to keep her legs warm, and Williams wanted to prevent post-pregnancy blood clots — the reaction to their outfits alluded more to discomfort with women’s assertive power and bodies, than to any fashion sensitivities.

Indeed, many interpreted the scrutiny towards Williams’s appearance as racist and misogynistic. It was Williams’s Black body, aggressive game style, and dominance of the field that were at the center of the policing of her outfit, not the fact that she abandoned the traditional skirt.

Serena and her sister Venus are no strangers to fashion scandals. Even when they have adhered to norms of femininity, the Williams sisters have been censured. In 2010, Venus’s black and red lacy, corset-like outfit was deemed “too sexy for the game” at the French Open, and in 2017 at Wimbledon, she was made to replace her bra mid-game after her pink straps were showing. Serena also drew headlines a few months after her catsuit scandal, when she played in the U.S. Open with a one-sleeve lavender tutu dress with fishnet compression tights, custom-made by the late Black designer Virgil Abloh.

The continuous attention to women’s appearances on the court, despite the growing acceptance of their presence in the sport, is a perfect example of the French saying: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (The more that changes, the more it stays the same). No matter how many barriers women break in tennis, what they wear remains the center of attention.

As we are entering the Grand Slam tournament season, people’s attention once again will be focused on the players, and with that on what they wear. But with regard to fashion scandals, it might be better to listen to Billie Jean King, who commented that “the policing of women’s bodies must end.” It is now time to focus on the talent.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great new article Einav. It’s a wonder women could play tennis as well as they did in the 19th and early 20th centuries with all the clothing obstacles they had to overcome. Your historical research here is wonderful, and the illustrations, photos, video, appreciated.

Thanks for including the beautiful 1907 George Brehm Post cover. A rare split-second ‘action’ cover, it has an almost 3-D look to it. Let’s hope the majority of attention will be focused on the players and much less on what they’re wearing. This includes common sense trying to avoid controversy upfront, so the policing of women’s bodies and/or clothing will hopefully (at worst) be minimal.