With hands that skillfully smooth the fabric she guides below the presser foot of her sewing machine, Torreah “Cookie” Washington begins another day of quilting. She has lived in Goose Creek, South Carolina, for about 38 years — perhaps a long time, but Washington is still considered a comeyah (someone not native to the area). A fourth-generation needleworker, at the age of 4 she sold her first garment, a Barbie dress, to her grandfather for 50 cents.

After a career designing wedding dresses, she was inspired to take up art quilting during her visit to a 1999 exhibit at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston called A Communion of the Spirits: African-American Quilters, Preservers, and Their Stories, based on the book by Roland L. Freeman. The photographer documented Black quilting practices throughout the United States, and the book contains nearly 400 pages of profiles and images of quiltmakers and their artwork.

As part of the exhibit, Washington saw a quilt made by Hystercine Rankin, a Mississippi woman who made memory quilts depicting scenes from her family life. Rankin’s recollections in cloth included picking cotton, going to church in a horse-drawn wagon, and her father’s shooting death at the hands of a white man who was never brought to justice. “I realized that I could put my voice and heart into cloth, say things I wanted to say, and acknowledge history in this way,” Washington says.

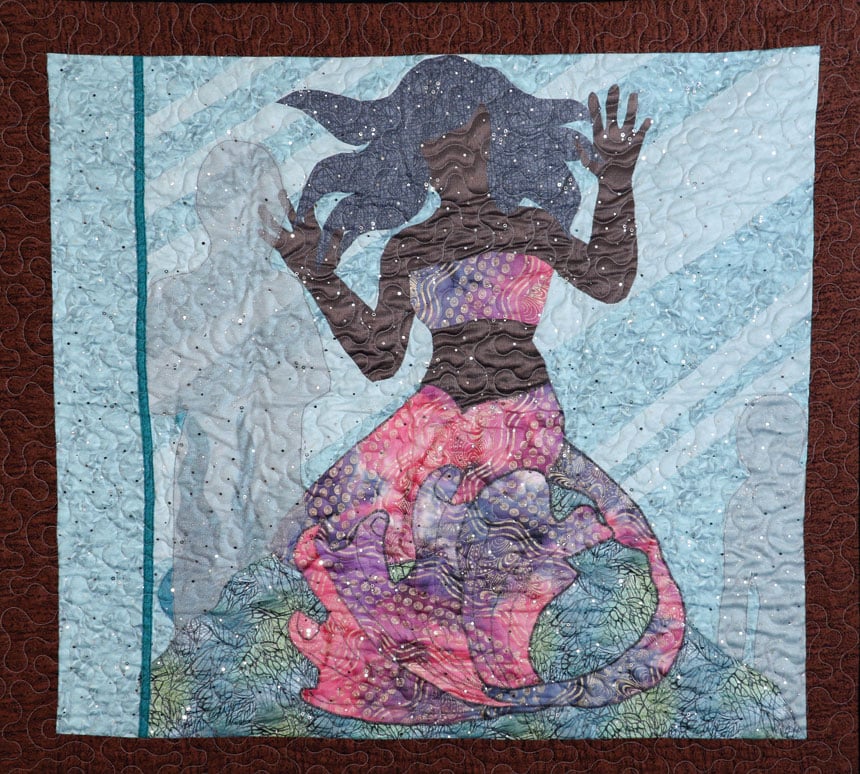

“vibrant visual tales told in cloth.” (Image courtesy Cookie Washington)

Washington’s first few quilts were misshapen and not quite what she’d imagined, but she kept working. “I have a really deep prayer life,” she says. “I started praying to God, Jesus, and the universe to help inspire me with subjects for my quilts. In response, I swear God said: ‘Black Madonnas.’ My first thought was, ‘But I’m a Baptist.’”

Washington started researching, and the first example she found was the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, in Poland. It was the subject of her first Black Madonna quilt, for which she used brown fabric and dreadlocks in depicting the Madonna and baby Jesus. From then on, she followed her inspiration to design quilted murals that pay tribute to her African-American heritage, family tree, and celebration of the divine feminine in spirit, because she feels that it is important to show young girls that the history of Black women didn’t begin on a plantation in the American South. She was asked to be one of the 44 master quilters to make a quilt to commemorate Barack Obama’s 2009 presidential inauguration.

In 2012, she created and curated a quilting exhibition, Mermaids and Merwomen in Black Folklore, for people to learn more about the worship of mermaids and water spirits that in many African cultures predates the worship of Jesus. “I believe that one of the major responsibilities of the artist is to help people understand something intellectually, feel it emotionally, and engage with it physically,” she says.

While her Black Madonna and black mermaid quilts have been the great art love affair of Washington’s life, it was the illness of dear friend Sharon Cooper-Murray (long known as “The Gullah Lady”) that led her to teach the craft of Gullah rag quilts. Passed down generation to generation, the no-sew technique traditionally combined feed and grain sacks with rag strips. A large nail was used to push the fabric into the burlap, and the individual strips were tied in knots. The cultural anchor preserves the legacy of using scraps to create something new, meaningful, and beautiful.

“It’s fairly simple, but time consuming,” says Washington. “Especially for our enslaved ancestors, because they were only using scraps. If you look at very old Gullah rag quilts, other old clothes or rags were used to line the inside, for warmth.”

Descendants of Africans who were enslaved on the lower Atlantic coast plantations of indigo, rice, and Sea Island cotton, the Gullah Geechee people have kept a rich culture of arts, crafts, foodways, language, and music. Their creole language began as a simplified form of communication among people who spoke different languages, and is spoken nowhere else in the world. While many elements of the culture are celebrated and visible to visitors to the region, their sustainability relies on being nourished and passed down through the years.

Washington made her first rag quilt with the kente cloth fabric of two skirts that had languished in her closet. She remembered being taught the technique by her maternal grandmother for a similar item — an Amish “toothbrush” knot rug, so called because some people fashion toothbrushes to be used as needles to aid in the rug creation.

“I’m not Gullah,” she says, “and I wasn’t sure if it was appropriate for me to step in. But I didn’t want the tradition to die out because few others are teaching it, so I asked some well-respected people in the Gullah community. They were enthusiastic and expressed interest in my being a culture keeper.”

As it turns out, “The Gullah Lady” Cooper-Murray isn’t Gullah either, but dedicated herself to understanding the culture after marrying her husband — a Gullah descendant and native of Wadmalaw Island, one of the Sea Islands, a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic coast. After many years of study, she became a popular Gullah-speaking storyteller who also taught workshops of rag quilting after she learned that many of the traditional quilters had died or grown too old to tie the knots. As one of the few people familiar with the folk art, she felt a responsibility to spread awareness of the practice.

In continuing the tradition, Washington adds a global responsibility not only for rag quilting, but also for leaving the Earth in a better condition for future generations. “My mother and brother died within 90 days of each other in 2023,” she says. “In going through the mourning process, I had trouble parting with their clothes. I found a big piece of scrap material from the last blouse I’d made my mother and a very old, nearly dissolving photo of my grandmother teaching me to make the toothbrush rag rug. I felt it was a message that I could create something by crocheting with fabric, and I made my first rag basket, using repurposed clothing.”

With the world producing 92 million tons of textile waste every year (of which the United States produces about 17 million tons), Washington emphasizes reducing and reusing fabrics in her quilting practice. And she’s become known for it. People keep giving her textiles, whether they find her in church, in her neighborhood, or in a workshop. She has fabric stored in the trunk of her car. The embarrassment of riches has inspired her to teach rag crochet, twining, and weaving to anyone who is interested.

Washington created and continues to curate the annual African American Fiber Exhibit, part of the North Charleston Arts Festival. This year marked the 18th year of the exhibit (held April 30-June 15, 2025) and included more than 60 artists from 22 states, with more than 75 pieces of art corresponding to the theme “In Praise of the Ancestors.” She’s also taught quilting workshops at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Washington currently gives Gullah rag rug workshops in the Charleston area, including Middleton Place and the Charleston Museum. “She’s a very important part of this museum,” says Jennifer McCormick, chief curator and archivist at the Charleston Museum. “She’s open and honest, and she has a vision with her quilts that not a lot of people have. It’s been a true joy to work with her.”

Washington’s art quilt honoring the victims and survivors of the 2015 Mother Emanuel AME Church shooting is part of the Charleston Museum’s new exhibit — Beyond the Ashes: The Lowcountry’s New Beginnings. “I knew Pastor Clementa Pinckney long before he became a minister,” she says. “I’d given him one of my Black Madonna quilts, and when it had returned from being on a touring exhibit, we’d made arrangements to meet for lunch on June 19 so I could give it back to him. He was assassinated two days before that. When the Charleston Museum asked me to make a tribute quilt, I said yes. My purpose is to show the community the healing power of storytelling through textile.”

Part of that storytelling is the responsibility of how a person or an event is represented. For the past three years, Washington has been working on a quilt featuring Cathay Williams. Although over 400 women served in the Civil War posing as male soldiers (women were prohibited from military service at that time ), Williams was the first African-American woman to enlist in the U.S. Army while disguised as a man. As a soldier, she became known as William Cathay, including with the emerging all-Black regiment that would eventually become part of the legendary Buffalo Soldiers.

“I didn’t know her,” says Washington. “I don’t know how she identified her gender — whether she merely dressed as a man to get by or had a more nuanced identity. I need to take my time to honor her and get this right.”

About the power of her work, Washington says, “Art is not a solitary event. It’s where people can come together to share a common experience, even if they see the world in radically different ways.”

Jill K. Robinson writes about travel and adventure for National Geographic, AFAR, Condé Nast Traveler, Travel + Leisure, Sierra, and a wide variety of other print and digital publications. She has received four Lowell Thomas Awards from the Society of American Travel Writers Foundation, including the 2024 Silver Award for Travel Journalist of the Year.

This article is featured in the July/August 2025 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What a wonderful story and I so enjoyed this fine, fine workmanship!!! This was a very inspiring article. Thank you so much for this.

What a powerful and moving article. It’s truly amazing how something originally meant to provide warmth—like a quilt—can evolve into such a captivating medium for storytelling and healing.

My mother is Hystercine Rankin, and I am the oldest of her seven children. We are incredibly proud of her trailblazing legacy. After enduring traumatic experiences, including the heartbreaking murder of her father, quilting became more than just a craft—it became therapy, expression, and ultimately, justice.

Through her storytelling quilts, Mama found a way to process her pain and share her truth with the world. In her own way, she honored her father’s memory and shed light on the experiences of her life and community.

Thank you for celebrating the power of textile art to tell the stories that matter most.

Myrtis Rankin