In a Word: The Racist Origins of ‘Bulldozer’

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When you see the word bulldozer, you might conjure an image of a large yellow machine with caterpillar treads flattening everything before it with its steel-toothed blade. Or maybe your mind goes back to a smaller Tonka version of this mechanical behemoth that you played with as a child. Taken on its own, with no context, bulldozer might even call to mind some serene bovine scene, perhaps Ferdinand the Bull dozing among the daisies.

How jarring, then, to discover bulldozer’s horrible, violent beginnings.

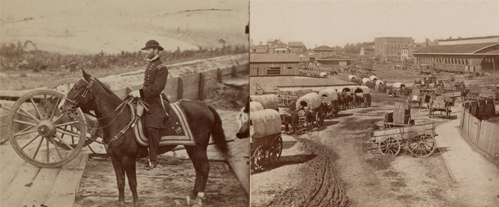

Bulldozer (originally spelled bulldoser) first appeared in the run-up to the election of 1876. That was the final year of President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term in office, and he had unexpectedly declined to run for a third term. In his place, the Republican party put its support behind Ohio Governor and former U.S. Representative Rutherford B. Hayes, while the Democratic candidate was New York Governor Samuel Tilden.

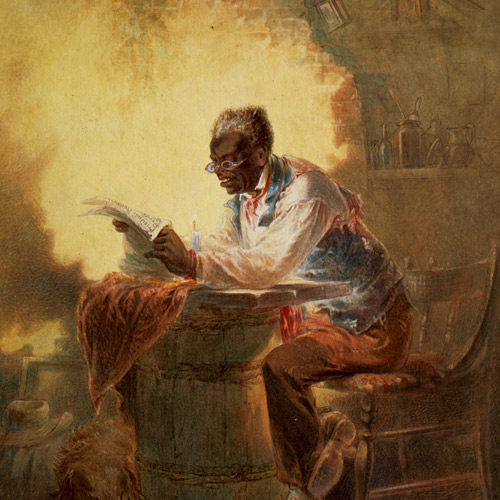

This was an important election. All the former Confederate states had returned to the Union, post-Civil War Reconstruction was ongoing, and this was the first presidential election in which African-American men could vote for someone who wasn’t Ulysses S. Grant. The outcome of the election of 1876 would shape the future of the South for years to come.

The former slave owners and secessionists in the South knew it, and they weren’t about to sit back and let the North and their former slaves usurp their power and privilege. Despite three new federal laws in 1870 and ’71 designed to protect Black Americans from violence and coercion at the polls, many were bulldosed into silence. Bulldose was a slang term derived from either “a dose fit for a bull” or “a dose of the bull” — the second being a reference to the bullwhip. Bulldosers used physical violence against Black voters either to keep them from the polls or to intimidate them into voting Democratic.

Going into the election, in five states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — a majority of registered voters were African American. One would expect, in a fair election, that the Republican candidate would easily take these states. But after the votes were tallied, Tilden had won the popular vote in Alabama and Mississippi.

The results in the other three states were even more unexpected. After counting had finished, both parties claimed victory in those states. On election night, Tilden was the presumed winner with 184 electoral votes, 19 votes ahead of Hayes and 1 vote away from holding a majority.

The 20 electoral votes of these states (plus Oregon) remained undecided for months as first the two parties and then the two houses of Congress launched separate investigations. Democrats and the Democratic-controlled House committee accused the Republicans of ballot stuffing and coercion. Republicans and the Republican-controlled Senate committee accused the Democrats of the same.

In the end, the presidential election was decided behind closed doors. In what came to be called the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats conceded the remaining electoral votes to the Republicans, making Rutherford Hayes our 19th president, but in return, federal troops were to be removed from the South, essentially ending Reconstruction and returning power to the same men who had controlled the South during the Civil War.

Though violent intimidation at the polls certainly continued, Southern officials found new ways to suppress the Black vote, including Jim Crow laws and grandfather clauses. Bulldosing took on the wider meaning of “to coerce or restrain by use of force,” and it was ripe for a more literal use when large, seemingly unstoppable machines came on the scene.

The machine we think of as a bulldozer was invented in the early 1920s, and by the initial months of the Great Depression, we start to find the term bulldozer in writing, with that Z further obscuring the word’s origins. The violent, racist origin of bulldozer is one reason many people now use the term earth mover to describe these massive machines.

If you’d like to learn more about the election of 1876 — including commentary from the Post while the election results were in flux — read “The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History.”

Featured image: Andrey Yurlov / Shutterstock

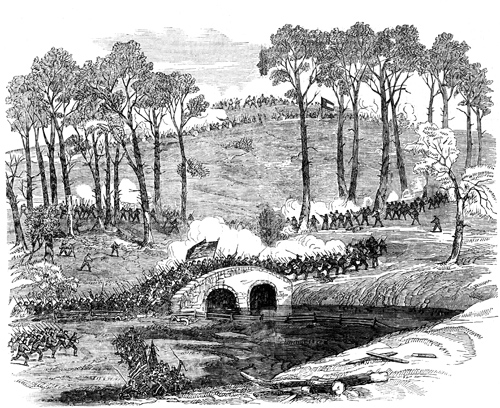

The War That Made Us Who We Are

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the March/April 2011 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

The war fought by Americans against Americans on American soil, for four excruciating years is still the deadliest war in American history. More than 600,000 fighting men were killed, some of them brothers in arms against brothers, and uncounted civilians died. It was a war over nothing less than whether to preserve or end the United States of America.

Most armed conflicts are about territory. This one was about ideas. The war would put an end to slavery. It would also create, if painfully, a cohesive single republic — more united than it had ever been before. In fact, the Civil War transformed the United States from a plural noun to a singular one. Before, you would say the United States “are.” Ever since the war, we say the United States “is.”

War became inevitable in December 1860, when South Carolina declared that it would no longer be a part of the United States. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president, and the Southern states were convinced he would immediately outlaw slavery, on which their economy depended. They resolved to leave the Union rather than have their way of life overthrown. In February 1861, South Carolina and five other states announced that they were now the Confederate States of America. U.S. Army forces had to retreat to Fort Sumter, a granite fortification in the harbor of Charleston. When the forces refused to leave Fort Sumter, state militiamen waited, wore them down by preventing supplies from getting through, and then opened artillery fire on them. The bombardment lasted for 33 hours, until 4,000 shots and shells set Fort Sumter on fire. Finally, the U.S. flag came down, and the Fort surrendered.

No one imagined how long and devastating the war would be. The first big battle was fought in July 1861, at Bull Run in Virginia, near Washington, D.C., where Union troops attacked Confederate forces in hopes of putting a quick end to the conflict. The Confederates withstood the assault and then counterattacked, and the battle turned into a rout of the Union forces. Many hundreds on both sides were killed, and thousands more were injured. Americans began to see what a long nightmare they had trapped themselves in.

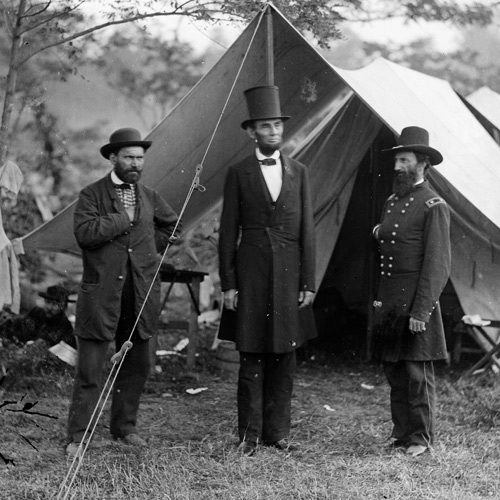

For more than a year after that, Southern troops won victory after victory under a brilliant general, Robert E. Lee, while Lincoln was disappointed by one irresolute Union general after another. One of the first big wins for the North was at The Battle of Antietam, in September 1862. The day it was fought remains the bloodiest day in American his- tory, with 23,000 casualties. Antietam turned a corner for the Union by stopping a northward advance by Lee’s army, and that victory gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. On September 22, 1862, he made the sweeping, revolutionary announcement that all slaves in Confederate states would be free as of the following January 1.

Since the Proclamation applied only in states the federal government had no control over, it didn’t really free any- one except in a few Union-occupied parts of Confederate territory. But it told the world — and the captive blacks of the American South — that the war was not simply about preserving the Union. It was undeniably about slavery.

The war dragged on, with both sides more determined than ever after the Emancipation Proclamation. A turning point was reached in early July 1863, when Confeder- ate troops that had invaded the North were turned back in the epochal three-day battle in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, while in Mississippi, Union forces took control of the city of Vicksburg, freeing the Mississippi River from the Con- federacy. As President Lincoln put it, “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” That fall he delivered his great speech at the battlefield in Gettysburg, where 170,000 soldiers had clashed and 7,500 had been killed, saying “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Many thousands more were yet to die, though. Lincoln finally found the commanding general he had been looking for in Ulysses S. Grant, and Grant pursued a relentless war of attrition against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, while General William T. Sherman cut a crippling swath through Georgia, devastating the heart of the deep South. The war dragged on until April 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Just a week later, President Lincoln was assassinated by an enraged Confederate sympathizer, John Wilkes Booth.

The wounds left by the war did not quickly or easily heal. Reconstruction, a bitterly opposed attempt by the North to remake the South, lasted until 1877 and ultimately failed.

The Civil War brought an end to slavery and reunited the nation, but the pain of reconciling the differences, many of which began with the birth of the republic, lingers still. The war made our motto true E pluribus unum — from many, one — but the work of making us one is never complete.

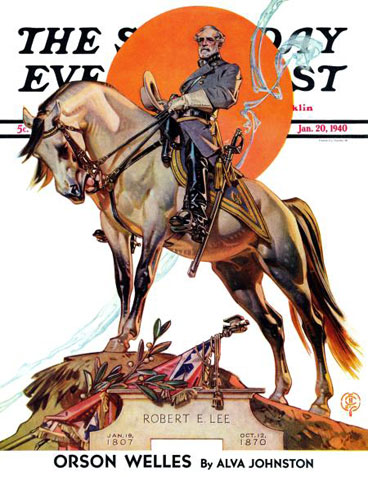

Let’s End the Civil War

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the August 11, 1962, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

There were more Confederate flags sold during the first year of the Civil War Centennial (1961) than were sold throughout the South during the war itself (1861-1865). One hesitates to estimate the number of Confederate flags that will be sold during the next three years, but the prospects are that the total will be more than all the flags sold in all the wars the nation has fought.

Yet the Civil War Centennial is hardly a promotion dreamed up by flag manufacturers. Nor is the centennial merely a project of the enthusiastic city booster to lure the tourist dollar to his hometown. No city booster anywhere in the south or in the north has any intention of proposing a celebration of other conflicts like World War I or World War II or the Korean War.

We celebrate no other war because essentially we believe those wars are over, their outcomes final, the course of history decided. But there are centennial committees throughout the south which would have us think the Civil War is not completely done with, that it ought to be refought. These fellows grow beards, wave flags, and charge over the few meadows the housing developers have left — hoping somehow by this exertion to sustain the illusion that the South may yet snatch victory from defeat. They do everything to re-create the Old South except save Confederate money.

The war started again in July 1961 with the grand reenactment of the Battle of First Manassas (Bull Run), which the South, not surprisingly, won again. Twenty-three states on both sides sent participants, although a large number of soldiers came from the ranks of the North-South Skirmish Association, an organization founded in 1950 by devotees of the muzzle-loading rifle, whose purpose is to hold shooting contests from time to time. For the First Manassas reenactments the participants wore authentic uniforms and carried old muskets whose blank cartridges often bruised the shoulder, blacked the face, and seared the eyes of the unwary.

The son of a friend of mine, a “corporal” in the Guilford Greys (Greensboro, North Carolina), has been “killed” three times since First Manassas and is perfectly willing to give his life in a fourth reenacted battle. It is nice , indeed, to have more than one life to give to one’s country, although the plane fare to the different battlefields is considerable.

The centennial engenders nothing if not sacrifice. The late Bill Polk, editor of the Greensboro Daily News, once showed me a letter from a North Carolina high-school boy which read, in part: “I wish I had been born before the Civil War and had died at Gettysburg.” These mock recruits, I suspect, secretly hope one day the batteries will load real projectiles in the cannons, and the bayonets will be cold steel, not rubber. And this time they will take Washington, D.C.

On To Washington! On To Yesterday!

Certain centennialists seem to believe that once they take the capital, they can force upon the Supreme Court the decisions that will restore the old plantations, the crinolines, the dueling pistols, the house on the hill with smoke coming out the chimney at twilight, and little Sambo rolling in laughter under the magnolia. Ah, what a glorious dream!

Yet it is not entirely an idle dream. The Civil War centennialists have some vague idea that, if they can mount a sufficient show of force, they may not have to deal with the more aggravating and immediate problems of Southern life — the problems that press upon an urban, industrial area that is leaving behind the old, easy agrarian values.

Thus the centennial has turned into a party rather than a pageant. I have even seen a few automobiles decorated with the Stars and Bars, filled with black students, each of the occupants therein wearing the butternut-gray dinks of Confederate soldiers. No centennial committeeman, no matter how skillfully he ties his bowstring, is completely unaware of what is going on in the business district of his hometown. He doesn’t even have to work behind a store counter to know that, in the states of the old Confederacy, at least one-third of all the purchasing power and one-half of all the credit buying comes from the pockets of grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the black slaves.

That realization is why the centennial is something less than a huge success in the big Southern cities. The plan for my own home, Charlotte, North Carolina, by far the largest city of the two Carolinas, was to commemorate the fact that it was the site of the Confederate Navy Yard. It seems that, after the war broke out, the naval stores at Portsmouth, Virginia, were seized and transported inland to Charlotte. The long boardwalk is still called “the wharf.” But except for the members of the committee itself, few people are even aware of the centennial, let alone a Confederate Navy Yard.

Was the “Old South” A Myth?

The chamber-of-commerce fellows are selling the ideals of the modern industrial world because the ideals of the Old South were only make-believe currency. There were Southerners before 1800, but there was no “Old South.” One of our Southern writers, Wilbur J. Cash, in his book The Mind of the South, recalled that boys who cleared out the Indians in the Carolina backwoods lived to command brigades at Bull Run, which means that the Old South could not have been more than two generations old.

The fact is that the Old South was nothing more than a myth and a poem and, as Jimmy Street, another Southern writer, put it, a malady for which there fortunately is a vaccine — the industrial payroll.

The Civil War started with the Negro in slave cabins. But all of the blanks and muskets and beards will not disguise the truth that Negroes serve today on the Republican and Democratic national committees. The real Confederates found cover behind occasional tar-paper shacks. In their place today, the re-created regiments and brigades have to charge around factories where the skilled workmen inside knock off a few minutes to cheer them on.

The time has come to end the Civil War because we are one country with one economy. We cannot take time out from industrial and urban problems of unemployment, housing, schooling, and civil rights to indulge ourselves in silly excess, celebrating a time that no longer is — and never was. The truth is that, at best, the centennial provides but a minor amusement.

“Lets End the Civil War,” August 11, 1962

The Civil War: One Woman’s Ordeal

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the July 22, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

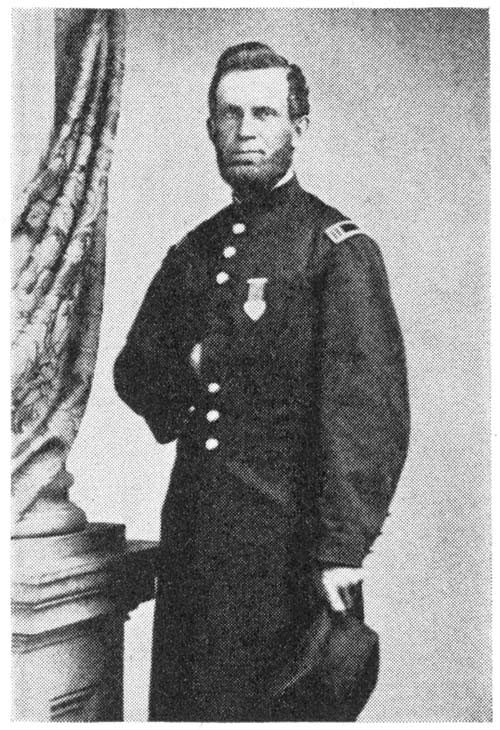

For two memorable, action-packed months in 1863, 19-year-old Lucy Bundy Cobb found herself caught up in the crazy whirl of the Civil War. She hurried from her home in Ohio to Winchester, Virginia, to nurse her ill husband, a Union officer. The Confederates seized Winchester and captured both of them. Lucy was sent to a prison in Richmond and exchanged without knowing her husband’s fate. A keen and sensitive observer, she related her experiences in later years to her son, Howard Bundy Cobb, and a grandson, retired Col. Ralph C. Benner. Cobb wrote down her story and Benner preserved the manuscript, giving us a rare and exciting insight to Civil War life and adventure.

* * *

In the telegram the colonel commanding the 116th Ohio Volunteer Infantry requested that I come at once. My husband and other officers had typhoid fever, and nurses were needed badly at the hospital in Winchester, a Virginia city which our troops had occupied.

At the head of his own company of recruits, John Haskell Cobb had left me on our farm in southeastern Ohio scarcely a year before. With the help of an occasional old man or boy, my Aunt Sarah and I had managed to put in a crop to feed ourselves and our livestock.

My father, Congressman Hezekiah S. Bundy, hurried up the path to our farm cottage as soon as he learned of the telegram. “Lu,” he began fussily, “get ready immediately. I must go back to Washington soon anyway, and will take you directly to the Secretary of War for authorization to join your husband.”

Hurriedly assembling what few clothes I found suitable, I clambered into father’s low-swung carriage. The going was slow, but we finally boarded the smoky old railway coach and patiently slept in our seats through the night trip to the capital. The next morning found us in the office of the Secretary of War.

The voice of Secretary Edwin M. Stanton seemed to come from the depths of his iron-gray beard. “Congressman Bundy, I’ll grant this pass for your daughter, but if she were my daughter, I’d send her home. Too many officers’ wives are going to the battle front. A girl of 19 should be far from the scenes of war!”

Vividly the words of that telegram came to me, and my face must have changed expression. “No, no! I cannot turn back now. John needs me. I must go!” My voice evidently held a pleading note, for the Secretary of War grimly signed his name to a paper which he handed me. “May God be with you,” he said gently. Then, turning away hastily, he seemed to dismiss me to a foolhardy venture.

I was wholly unprepared for what I was to find in Winchester. This little town in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley changed hands between the North and the South many times during the war. This morning, however, it lay calmly in the sun under the old Star Fort whose earthworks frowned down on the cluster of cottages where the Union Army had its headquarters.

No one received me at the dwelling where I dismounted from the stage and struggled with my carpetbag. And my knock received no reply. The front room was evidently an office, so I ventured timidly into the house. From the rear I heard a sound which filled me with misgiving. Dropping my bag, I hastened in the direction of that feverish moan.

“John!” I cried, only to receive a vacant stare as he tossed about in bed in a tangle of sheets. My heavily bearded young husband had lost many pounds. I seized his weak, thin shoulders, pressing him back gently onto the none-too-clean pillow. He yielded to my ministrations without giving a sign of recognition.

Anxious days followed. John lay feeble and helpless, feverishly trying to lead his men against imaginary breast-works manned by “Johnny Rebs” blazing away. It was a lengthy vigil. But when John’s eyes opened with awareness and he murmured, “Lu!” the weak smile with which he greeted me left me breathless. The tension was broken. Tears came to my eyes for the first time, and I sank down on the bed in relief.

John was soon sitting up, but I kept close to my convalescent husband. Soon the rumblings of war drew nearer. The Confederate Army, if not blocked, would soon engage Star Fort. Our entire regiment was thrown into action.

For hours the din of battle kept coming across the brow of a nearby hill. Soon noncombatants and stragglers entered town, bringing to me a glimpse of the meaning of war. As evening approached, I became prepared for most any eventuality. There came an order to all noncombatants. “We must go up to the fort,” John announced.

Star Fort was nothing more than a hollowed-out earth-works on the brow of a hill overlooking Winchester. Noncombatants huddled in one corner. Gunners and swarms of infantrymen milled about in confusion. We watched apathetically while the Union flag was lowered from the main staff. I experienced a feeling of helplessness as a white cloth was run up in its stead. The firing ceased. Columns of troops marched out in surrender. Then there appeared the first gray uniforms I had ever seen. Where Old Glory had waved but half an hour before, we watched the Stars and Bars rise! I looked from the flag to John’s face for reassurance. There was none. Instead, with compressed lips, he handed me his watch. “Here, Lu,” he said tonelessly, “hide this among your petticoats. No rebel shall wear it. Smuggle it through the lines when you are exchanged.”

“John! We are not to be separated,” I cried, clinging to his sleeve. “I’ll not leave you here.” Then several other facts became clear to me. “Is there danger of you being sent to Libby Prison?”

Very soon, several Confederate officers came up and said all women would soon be transported to Richmond.

I rushed back to John, bursting into tears. That awful name “Richmond” filled me with such fright that I closed my eyes and hid my head on his shoulder. I was still clinging desperately to him when a rebel private soldier forcibly but gently released my grasp, saying, “Sorry, lady, but it is the captain’s orders. You need have no fear of us Southerners. We never hurt a lady.” John, weak and pale, let his arms fall to his sides. He swayed and nearly fell.

Common transport wagons, pulled by four horses, were ready for us. Sitting on straw on the wagon floors, we journeyed for long, weary days into the South. Our greatest concern was for food. As it was next to impossible to obtain fresh food, offerings from charitable Southerners along the way were welcomed. At one village where the women appeared particularly desirous of giving us food, however, they did it in a surly manner with many an ugly curl marring the symmetry of a pretty lip. The sandwiches looked good and fresh. The bread was clean and handed us in clean paper. But intuition filled us with suspicion. We noticed the younger women and children, particularly, gazing at us as if expecting some demonstration. There were facial demonstrations very soon. For when we half- famished women bit into the sandwiches, we discovered the bread had been spread with soap! The Southern women screeched and howled with amusement as we threw the bread away, violently wiping out dry and soapy mouths. The guards, however, were more than apologetic for the shameless womenfolk.

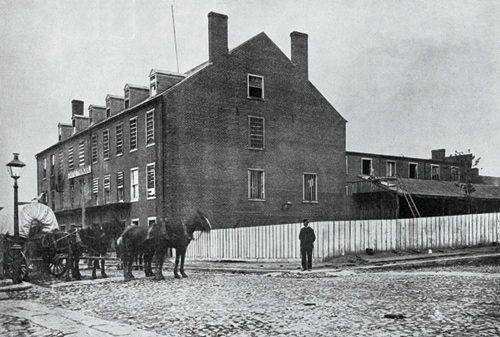

Finally arriving in Richmond, we were taken directly to an old tobacco warehouse across from historic Libby Prison. From the barred windows of our jail, nicknamed “Castle Thunder,” we could see Union soldiers pacing back and forth in old Libby, where I was fearful John would eventually be imprisoned. Days of idleness followed.

On the 14th day, word came that our exchange had been effected. No group of prisoners was more grateful for freedom than we Northern women. But our preparations were marred by wistful glances across at grim old Libby. Perhaps our husbands languished behind those ugly walls.

Aroused at 2 a.m. on a June day in 1863, 42 women prisoners were marched down the three flights of rickety warehouse stairs, out into the dim light of Richmond streets, to the bank of the James River. A makeshift bridge of two planks led over the murky water to the boats. Once safe on the opposite shore, we boarded a flag-of-truce vessel and steamed by way of the James River, Chesapeake Bay, and Potomac to Washington. Finally, I was allowed to go to Pittsburgh and then home.

I arrived at my destination with mixed feelings. For a moment I was glad. Then it came to me with a rush that I had failed! I had gone to bring back my sick husband. And here I was on the threshold, empty-handed. Aunt Sarah said nothing about John, and I was grateful. Soon I went out to the pasture where the farm horses grazed contentedly. My mare Polly loped over to me, thrusting her nose in welcome. I felt comforted. I tried to shut out the memory of war and was thankful that my Polly never would sniff burnt powder or hear the whiz of a Minié bullet.

On my third day at home, a disturbing conversation took place. Aunt Sarah, after talking with someone who paused outside her window, asked me, “Had you heard? Morgan’s Confederate raiders are coming up the river valley.”

My heart sank. “You don’t mean that his horsemen may overrun this farm! War does things to peaceful homes in the South. Surely we in Ohio are not faced with that kind of devastation!”

Soon a crowd of women gathered in the yard, evidently to see me. Many were wives of soldiers whom John had enlisted in his company. In the vanguard was Sally Saxe, whose husband I had last seen in the dim twilight of the Star Fort at Winchester, supporting my swaying John.

“Lucy,” Sally said anxiously, “you know about war. What air we goin’ to do? Morgan’s men may be jist over the hill. I’m scairt to death!”

I put a reassuring hand on her shoulder and spoke to the crowd. “Neighbors, the Confederate soldiers are not bad. I spent two months among them and they do not make war on women and children. They may take our feed and even our livestock, but they will not hurt you.”

Sally and some others were not convinced. “They may burn our houses or carry us off!” she wailed. Others joined in the cry.

By the next dawn, gray horsemen appeared from all directions as if they had dropped from the skies. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, a dashing cavalryman with a full mustache and pointed beard, rode up to the farm majestically. He quartered a detachment of men overnight in our barn. Soon I heard a firm knock at my kitchen door. It proved to be one of Morgan’s officers.

“Madam, have you flour in your house? You have some hungry visitors. We’ll have to ask you for food.”

I answered him calmly, in a tone as neutral as possible. “Yes, sir, I have flour. How much of it do you want?”

Removing his hat, he appeared embarrassed. Then he explained. “You see, lady, actually we can’t use flour. We are asking you to bake us a batch of bread — a big batch, all the flour you have in the house. We are hungry and we are living off the country as we go.”

“Very well,” I answered, “but it must be made from biscuit dough. There is no time for yeast bread.”

“Thanks, lady, any kind of bread will do.” The soldier smiled appreciatively and backed away. However, I saw him eying our speckled hens and broods of fryers, and surmised correctly that they would disappear before morning. We baked bread until our backs felt broken and the larder was almost empty — all but what Aunt Sarah had grimly secreted in the attic. She planned not to starve.

Yet it was a relief to be left some property. I began to feel safer, when a commotion in the barnyard brought back all my dread. Three burly soldiers closed in on Polly and slipped a rope over her silky neck. I grabbed the rude halter and turned wrathfully on the three men. “You can’t have Polly!” I stormed. “Let go that rope. Let go, I say!” As I jerked the rope away from them, a sergeant came up.

“But, lady,” the sergeant began apologetically, “General Morgan gave orders we were to take all sound horses we needed, and no mere woman can interfere with us. We are not taking your farm team. We want only the mare and are leaving this Thoroughbred in exchange. He has a sore back and needs a long rest.”

I looked where he pointed. There, standing dejectedly, was a handsome Kentucky gelding, a standard-bred horse whose coal-black coat glistened in the morning sun. I reasoned that there was little I could do against these marauders. Sadly and slowly I released my hold on Polly and suffered her to be led away.

* * *

One morning, Ronald Saxe, Sally’s son, came up and burst out “Pa’s home!”.

As his father had been captured with my John, I grabbed his shoulders. “Why didn’t my husband come with him?” He hesitated. I shook him.

The boy broke into a stream of words. “Pa said he and Cpt. John slipped out of the prison stockade at Winchester the night after you left for Richmond. They got clean away and struck out north as fast as the captain could travel, hiding daytime and walking nights. They forded or swam rivers until they got into Ohio. They rested some and foraged for food too. Then they heard about Morgan’s raid. The captain insisted on going to head off the rebels. They crept up close to one of the rebs’ advance amps below Pomeroy at night. And what do you think? There was Polly, tied to a tree with some other horses.”

“The captain vowed he’d get Polly away from the rebs. Pa couldn’t stop him. That night, the two of them tried to steal Polly and another horse. But Polly gave them away. She neighed when she smelled familiar folks, and the guards pounced on them. They soon found out that your husband was a captain in the Union Army. So they held him. Gen. Morgan, they said, isn’t letting Yankee officers go because they are valuable for exchange. They let Pa go.”

I burst into tears. The boy stole silently away as if he had been guilty of some crime. The slow, creeping paralysis of war was enfolding us. Hours seemed to pass. Suddenly Pvt. Saxe and wife Sally rushed up to the door.

“Morgan was captured not 20 hours after he turned me loose,” Saxe shouted. “There is a chance that his prisoner detail never got back across the Ohio River,” Saxe explained. I sat silently, too tired to think. My gaze wandered out over the field and down the valley road. Suddenly my eyes became riveted to a familiar moving object. I got to my feet and advanced instinctively to the gate.

In a lather of foam, panting with her nostrils aquiver, Polly came to a stop. Her rider flung himself from the saddle. The mare stood motionless while my soldier husband gathered me into his arms.

“Lu!” he cried brokenly, while I could only reply, “John!”

— From “One Woman’s Ordeal,” from the July 22, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post

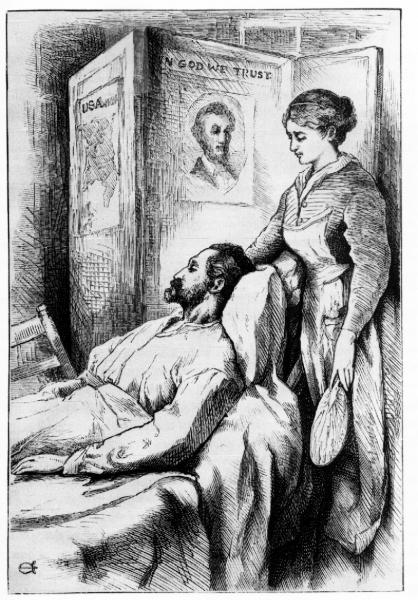

Civil War Hospital Sketches from Louisa May Alcott

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

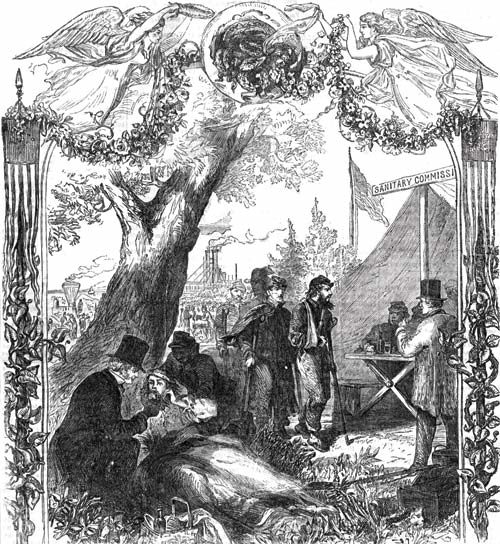

American novelist Louisa May Alcott wrote about her experiences as a Sanitary Commission nurse in a series of letters for the abolitionist Boston Commonwealth. The letters, published as Hosptial Sketches in 1863, earned Alcott her first public attention as an author and praise for her sensitivity and wit.

The Post published excerpts from Hospital Sketches, a few weeks after Gettysburg, when Union hospitals were overflowing with casualties from the battle. On these pages, Alcott describes caring for soldiers from Fredericksburg in December 1862.

* * *

They’ve come! they’ve come! Hurry up, ladies — you’re wanted.”

“Who have come? The Rebels?”

This sudden summons in the gray dawn was some- what startling to a three days’ nurse like myself, and, as the thundering knock came at our door, I sprang up in my bed, prepared “To gird my woman’s form, And on the ramparts die,” if necessary; but my room- mate took it more coolly, and, as she began a rapid toilet, answered my bewildered question, — (“Bless you, no child; it’s the wounded from Fredericksburg; forty ambulances are at the door, and we shall have our hands full in 15 minutes.”)

The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty.

I chanced to light on a withered old Irishman, wounded in the head. He was so overpowered by the honor of having a lady wash him, as he expressed it, that he did nothing but roll up his eyes, and bless me, in an irresistible style which was too much for my sense of the ludicrous; so we laughed together, and when I knelt down to take off his shoes, he wouldn’t hear of my touching “them dirty crayters”.

Some of them took the performance like sleepy children, leaning their tired heads against me as I worked, others looked grimly scandalized, and several of the roughest col- ored like bashful girls. One wore a soiled little bag about his neck, and, as I moved it, to bathe his wounded breast, I said,

“Your talisman didn’t save you, did it?”

“Well, I reckon it did, ma’am, for that shot would a gone a couple a inches deeper but for my old mammy’s camphor bag,” answered the cheerful philosopher.

Another, with a gun-shot wound through the cheek, asked for a looking-glass. When I brought one, regarded his swollen face with a dolorous expression, as he muttered —

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I warn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? and what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

He looked up at me with his one eye so appealingly, that I assured him that if Josephine was a girl of sense, she would admire the honorable scar.

The next scrubbee was a nice-looking lad, with a a bud- ding trace of gingerbread over the lip, which he called his beard, and defended stoutly, when the barber jocosely sug- gested its immolation. He lay on a bed, with one leg gone, and the right arm so shattered that it must evidently fol- low: yet the little Sergeant was as merry as if his afflictions were not worth lamenting over; and when a drop or two of salt water mingled with my suds at the sight of this strong young body, so marred and maimed, the boy looked up, with a brave smile, though there was a little quiver of the lips, as he said,

“Now don’t you fret yourself about me, miss; I’m first rate here, for it’s nuts to lie still on this bed, after knocking about in those confounded ambulances that shake what there is left of a fellow to jelly. I never was in one of these places before, and think this cleaning up a jolly thing for us, though I’m afraid it isn’t for you ladies.”

“Is this your first battle, Sergeant?”

“No, miss; I’ve been in six scrimmages, and never got a scratch till this last one; but it’s done the business pretty thoroughly for me, I should say. Lord! What a scramble there’ll be for arms and legs, when we old boys come out of our graves, on the Judgment Day: wonder if we shall get our own again? If we do, my leg will have to tramp from Fredericksburg, my arm from here, I suppose, and meet my body, wherever it may be.”

The fancy seemed to tickle him mightily.

Donation notes to Soldiers

Alcott volunteered with the Sanitary Commission, created in 1861 to help organize donations and volunteers. Throughout the war, the Post published Commission news, including the excerpt below.

— Originally published March 26, 1864 —

Some of the marks on the items sent to the sanitary Commission show the thought and feeling at home:

On a homespun blanket, worn, but washed as clean as snow, was pinned a bit of paper which said: “This blanket was carried by Milly Aldrich (who is ninety-three years old) down hill and up hill, one and a half miles, to be given to some soldier.”

On a bed quilt was pinned a card, saying: “My son is in the army. Whoever is made warm by this quilt, which i have worked on for six days and most all of six nights, let him remember his own mother’s love.”

On another blanket was this: “This blanket was used by a soldier in the war of 1812 — may it keep some soldier warm in this war against Traitors.”

On a pillow was written: “This pillow belonged to my little boy, who died resting on it; it is a precious treasure to me, but i give it for the soldiers.”

On a pair of woolen socks was written: “These stockings were knit by a little girl five years old, and she is going to knit some more, for Mother says it will help some poor soldier.”

On a bundle containing bandages was written: “This is a poor gift, but it is all i had: i have given my husband and my boy, and only wish i had more to give, but i haven’t.”

The Harrowing Story of the Civil War’s Refugees

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the October 1, 1864, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

It may seem superfluous to dwell upon a theme that everybody knows by heart. Hospital scenes have been recorded until all are familiar with them — but if you will permit me, reader, I will throw the door open upon another phase of life, and if you can look on unmoved, with no stirrings of divine pity and sympathy — I will not be your judge.

The headquarters of the ——— Army Corps was a large, beautiful building, and we took possession of it in the spring of ‘64 with not a little satisfaction. The rooms were numerous and comfortable, and by a little careful management we got enough furniture together to serve our purposes admirably. When all the arrangements were completed, I looked about me with the joyousness of a child, and, for the moment, gave myself up to anticipations of something like ease and pleasure, after long, tedious journeyings, and the hardships attendant upon the removal of headquarters from one point to another.

Several days passed away in a comfortable frame of mind, when I was suddenly startled from my serenity by a fearful announcement. The Rebels had risen up against the women and children within their lines, and they had driven them out by hundreds, seizing their scanty means, and leaving them destitute to wander off in search of aid and protection.

These people had friends in the Federal service, of course — hence this cruelty. But until that time I never dreamed that people could suffer what they were made to suffer, and live.

I remembered the evenings at Corinth, after its evacuation, when the Refugees had come in upon the trains in large numbers, half starved and destitute of money or clothing beyond what they wore. Gen. McPherson was then superintendent of the military railroads there, and I shall never forget the deep, pitying look of his eyes as he glanced upward to my window, where I stood tearfully regarding this miserable mass of humanity. I recognized in him then a nobility few saw, when he stretched his arms forth to help some poor old man or woman as they tottered to the platform, or to lift some little ragged child—white or black— gently to the ground. I thought of the misery of those people there and what labor it had cost us to save them from star- vation. Could assistance be less imperatively needed now?

As I passed beyond the threshold and entered the ambulance that stood waiting my orders, a thrill of shame swept through me at the sight of a squalid troop that crept hesitatingly toward business headquarters.

My driver was dispatched for a pass through the “picket lines,” in case it should be needed, and while he was gone, a negro boy told me of a family that were “starving to death,” just a little beyond the limits of the town. I made up my mind to go there first, leaving those within the place to the mercy of those who saw to their needs, and when the driver came, I bade him drive as rapidly as possible to the place.

After driving about one mile and a half, we came to an old house before which little fires were kindled, and the pickets sat by and chatted while on “guard.” I leaned forward and asked them some questions.

“Are there people ill in that house — refugees?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“How long have they been here?”

“Three or four days.”

“How is it then that none of you have reported it at head- quarters. Have you no feeling of pity?”

“Well, ma’am, I have, for one, but this is my first day on duty. I was sent to relieve a boy who is sick and was sent to the hospital yesterday. It was me that sent word to town about them.”

Waiting to say no more, I bade the man drive on, and the next moment alighted before the door.

All the lower rooms were bleak and desolate. The windows were broken, the floors covered with heaps of shattered plastering, sticks, and broken glass. Failing here to find any trace of human life, I mounted the stairs to the second floor, and stood mute with consternation upon the threshold of the wretched chamber.

This, like the room below, was open, bleak and dreary. A faint spark of fire glowed in the midst of a great heap of ashes upon the hearth, and before it, upon the bare, dirt-strewn floor, lay the insensible bodies of a mother and her son—a boy of about 14 years of age. Upon beds made of straw and old clothing, lay two daughters of about 18 and 20, likewise insensible from suffering. They occupied the farthest corner of the room; and in another corner, close to the mother were two more children upon an old bed—prob- ably the only thing they had succeeded in saving from the household wreck — and one was dead — the other too ill to help himself to a cup of water!

My heart ached — my eyes grew dim. For one moment, I breathed despairingly “what can I do, oh, what can I do?” In the next, a willing brain found a way to direct its energies, and I flew down stairs in eager haste, to the driver, who quietly awaited my orders.

“Go back to headquarters and tell the medical director to send me the articles marked down upon this paper,” I said, tearing a leaf from my diary and writing upon it. “You had better take out one of the horses, and have the other fastened securely in the yard. Hasten, for it is a matter of life

and death.”

He obeyed me readily, and in a moment or two after I went up stairs, I heard the horses’ feet clattering down the road in the direction of A———.

An old adage says “Where there is a will, there is a way,” and I realized its truth that day, if I never did before. There seemed ab- solutely nothing to do anything with, when I came to look about me for means to ac- complish the ends in view. One tin-cup and a water-pail, half full of water, constituted the furniture of the room; and a thorough search through the house and negro quarters, failed to produce anything better than an old tea-kettle with a broken nose, a sauce- pan cracked down one side, and a large tin pan, too full of tiny, rust-eaten holes for any other use than that I put it to—that of relieving the hearth of its too great abundance of ashes.

I found a little negro girl curiously peeping round, and pressed her into service to carry out the ashes, while one of the soldiers on picket duty, kindly cut up an armful of wood to build a fire. This done, I filled the tea-kettle and set it on the logs to heat, while I went out into the field to get a broom. This may sound oddly to the uninitiated, but for the benefit of the ignorant I will say that there is a tall, coarse kind of grass that grows South in the old fields and waste places, called “Broom sedge,” which when gathered and tied together, makes a tolerable broom. It enabled me to sweep a place large enough to draw the sick into, and by dint of much pulling and lifting, I finally succeeded in getting the room free of clay and ashes. The kind-hearted soldier gave me an old blanket he had outside, which I spread upon the floor to lay the dead child upon, covering the little stiffened form from sight while I worked. The mother was soon in his place upon the rude bed, and then began the task of bathing their faces and hands.

By the time this was finished, the boy came back with the articles I had sent for — some hot punch, in bottles — dried apples — bread — tea — sugar, and butter, with some potatoes and onions. I was exultant now. Before this generous supply, want shrank abashed, and the groans of the sick sounded positively sweet to my ears, since they proved that life was not yet extinct. I could not have borne to think they had all died almost within sound of my voice, while I sat in easy ignorance of their fate! That would have proved a bitter cup, to the end of my days.

The punch was administered first, all round — then I made some tea, which with crackers broken into it, I forced them to swallow. In less than an hour, the moans and broken exclamations subsided, and they slept almost peacefully!

Darkness came at last, and I must go home! Other duties as pressing, claimed my attention. But I found an old negro woman who promised to take my place, and watch with them through the night — for a consideration. So, leaving them to her care, I entered the ambulance to return to town, feeling exceedingly weary, but glad and grateful to have been instrumental in relieving suffering of such magnitude.

The rain had begun to fall by this time, and came down in a brisk shower as we drove through the streets by the depot. There I observed that the whole platform and build- ing, where a human being could creep for shelter, had been filled up — and some unable to get under a protecting roof, were gathered about fires in the open air, the rain pattering upon the little children, who clung to their mothers’ dresses and wept piteously.

Such experiences as this were not new to me. I was but living over the old time at Corinth; yet it affected me strangely. Perhaps I had grown more thoughtful as I grew older, and through suffering learned to sympathize more deeply with suffering. Not a few of my best beloved and honored friends had fallen, leaving my heart tender for blows that might come hereafter. This was one that wound- ed me. I was touched most deeply, when touched through remembrance of pain. Every heart-pang found a responsive throb in my own.

Lights blazed from every room in the house, and the table looked invitingly tempting, with its array of nice dishes, around which merry faces gathered as the officers came in and took their places; but I could not eat that night.

Those pinched and pallid faces of little wailing children rose up before my eyes, and arrested the food ere it touched my lips. It was with difficulty that I could command my- self long enough to utter an excuse and withdraw from the room, which I did amid smiles and exchanged glances. Even the sweet, earnest face of Gen. Grenville’s wife relaxed as one of the officers remarked jestingly:

“Mrs. ——— found those refugees too much for her appetite, I guess,” — and then a general laugh followed.

Alas! even in the midst of woe, there are few to care for the most wretched of human beings, with a care that can withstand all things.

I sat up until late that night, making a shroud for the dead boy, tears dropping often upon the shining needle as I sewed. …

The following morning I rode out very early, and found a decided improvement in the patients, which encouraged me very much. The death of the child had been properly reported the night previous, and soon after my arrival two or three men were sent to bury it. No tears fell for the little form when it was carried out. No eyes followed it with the wistful tenderness of love, or the mournful outbreaking of sorrow. But, all unconscious of the broken link, the mother, brother and sisters lay there upon the floor, while the sol- diers lifted the coffin and bore it thence, where they buried it among strangers, in an old graveyard, where the gray tombstones bore the traces of an hundred years on their defaced sides. Think of it, mothers, think of that unwept child — its lonely burial, and the condition of that mother who loved her darling children!

For many days I watched over this poor family at the picket lines, until they be- gan to recover — all except the eldest boy. There was no hope for him, and the week after my first visit he died. But the mother and daughters improved rapidly, and after a while could walk about the rooms with a dawning of hope upon their pale faces.

The noble-hearted physician who had attended them through their illness, had proved a great assistance to me in more ways than one during those trying days. Men from his corps of assistants at the hospital had been de- tailed to make bunks for the invalids, and by sewing wagon covers together, and filling them with husks, we succeeded in getting them off the hard floor and placing them in a much more comfortable position.

Others, as badly in need of help, claimed my attention at every turn.

Every vacant house and cellar in town were crowded with them. Provisions were scarce, and to get clothing was utterly impossible, except a few cast-oft garments that I begged from the few loyal ladies of the town. Everything that could be spared from my husband’s and my own ward- robes, as well as Mrs. Grenville’s, was used to clothe the little children until such a time as they could be sent North and properly provided for—a thing which could not be done until they recovered sufficiently to travel. In families of 10 and 15 members, scarcely one could be found well enough to wait upon the sick, and often not one. The most singular fatality seemed to attend them, and none escaped prostration by disease brought on by expo- sure, excitement, and want.

Reader, if you are disposed to look upon this as an overdrawn picture, go to Memphis or Nashville where they come in by thou- sands, and note the condition of that most miserable class of beings called Refugees.

“The Southern Refugees,” October 1, 1864

“How We Marched through Georgia” — A Union Soldier’s Tale of the Civil War

This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the May 20, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

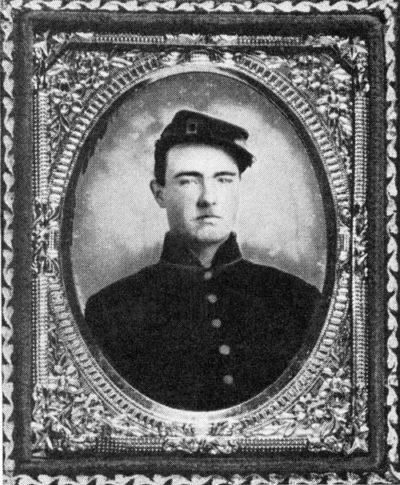

Robert Hale Strong was just 19 when he marched off to the Civil War with the 105th Illinois Union Volunteer Infantry and lived through grim fighting in the Georgia-Carolinas cam- paign. In his letters home, he told with brutal realism but unflagging good humor of humanity under fire and American courage of both sides. The following article is excerpted from that manuscript, later published under the title A Yankee Private’s Civil War.

* * *

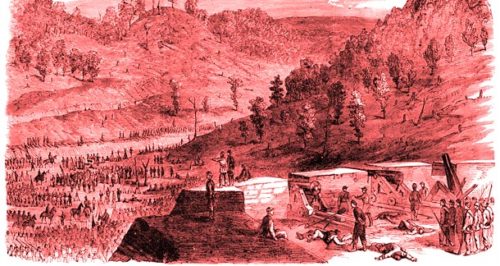

We were under fire every day for about a month between Buzzard Roost and Atlanta, Georgia. I don’t mean that we were in a big battle every day, but were in a fight or skirmish on the picket line, always firing at one another. All the way to Atlanta was a series of fights. We did not always have it our own way; the Rebs were as stubborn as mules.

One time the enemy’s range was extra good, I remember, and their shells and bullets kept us dodging busily. You must understand that it was no real use to dodge, as the balls would either hit or pass us quicker than we could dodge. Old Col. Dustin saw the boys dodging, and he sung out, “Stop that dodging. Stop it, I say!” Just then along came a shell pretty close to his head. He was on horseback, and he bowed his head almost to the saddlebow. The boys laughed, whooped, and yelled. The colonel straightened up and said, “Well, d—n it, dodge a little, then.”

That same day, it seems to me, we experienced the heaviest musketry and artillery fire that we had all through the war. We fought them all day. They were on an elevation, and it is a fact that after we were relieved and started to the rear we could see round shot roll along the ground with enough force to tear off a man’s foot, as one negro discovered who tried to stop one with his foot. About then I found I had lost my knife and my pocketbook. I started to go back to the rail fence where we had been, to look for them. When I got nearly there, I found the Rebs had taken possession, and I lost all desire to recover my property.

The second day of the fight, we had been advanced to- ward the enemy in the shape of an upside-down V, with our troops at the point and Rebs on each side and in front. We were in timber. Across an open field we could see the Rebs massing about 80 rods away for a charge. The 102nd Illinois, armed with Spencer rifles, seven-shooters, were deployed in front of us as skirmishers. As the Rebs would advance, the 102nd boys would open on them with their seven-shooters and pretty soon, back they would go, only to rally and try again. We could hear their officers cursing them for cowards to run from nothing more than a thin line of skirmishers.

Shortly after they quit coming for us, Gen. Joe Hooker rode up, looked around and asked, “Who has command of these troops?”

Brig. Gen. William T. Ward said, “I have, sir.”

“D—n you, sir,” says Hooker, “don’t you know you have got these boys in a trap? The enemy are on three sides of them and prepared to charge on each side. Recall everybody but skirmishers and tell them to fall back quietly — don’t let a tin cup rattle to tell the Rebs that we are moving.” So we got out of that, but it was a close call.

During the first part of the Atlanta Campaign, I messed with Matthias Stephens and Ernst Hymen, both good, quiet, religious boys. One night, after advancing and driving the enemy all day, my mess had gone to our pup tents, and we were talking about the probability of a battle on the morrow. I used some strong language about the enemy and about our having to work so hard on short rations. Stephens checked me, saying, “Don’t talk so. Some of us will be killed tomorrow in the fight.”

Well, early the next morning we began a running fight, with the enemy falling back slowly. In advancing, we took advantage of all the shelter we could get, behind logs or stumps. My position was on the right of the company, being one of the tallest boys, but of course in that kind of advance ranks are not kept very true. It got to be a pretty hot fight. I heard someone call out, “Strong — Bob Strong!”

Before I could answer, someone else says, “The man call- ing you is out there in front of the line.” I saw the hit man shudder and lay his head down on his arm. I knew he undoubtedly was killed, for if only wounded he would have called further for help.

The Rebels refused to be driven any farther for hours. It was nearly sundown when they pulled out and we advanced. Our boys all gathered around the fallen man in our immediate front. Sure enough, it was one of my messmates, Ernst Hymen. He was shot directly through the top of his head and probably never knew what hurt him. Our orders were to push on after the enemy, but a few of us remained, dug a pit and wrapped Ernst in a blanket in his lonely grave.

One day during a battle our brigade was ordered from center around to the right of the enemy. We marched just behind entrenchments filled with Yankees and across a field where we could see the enemies’ breastworks. We watched them working their artillery, with their shell and shot whistling over and among us. At the rear of the regiment were the major and Dr. Potter, brigade surgeon. If we saw a shell coming low, the men in line with it would lie down. One came along, striking the ground and rebounding. Dr. Potter with others was directly in line. Some lay down. Dr. Potter laughed at the boys. The shell struck the ground just in front of him, rebounded and took the top of his head off. As it hit him, a little puff went up from his head, and he fell dead. Then the shell struck the ground a few feet beyond him and stopped, with the fuse hissing. One of our boys ran to it and poured water from his canteen onto the fuse, putting it out and thereby probably saving many lives at the risk of his own.

At that point we were ordered to support a battery. As we came in sight of the battery, the Rebs, in three lines, They were about as near it as we were. We went on the run to save it. How those gunners did work those guns! At every discharge we could see holes open in the Johnnies’ ranks, but they closed up and kept on coming. When we reached our place behind the guns, the Rebs were not more than 100 feet away. Even in our hurry and great danger we handled our rifles as if on drill. Every man reached his place, pointed toward the enemy, and began firing. The Rebs were not more than 60 feet away. They went down like a boy shooting into a flock of blackbirds. It checked the charge, and the Rebs fell back. Our boys sent up a big cheer, then the battery boys had to shake hands with such of us as they could reach.

The enemy infantry having pulled back, their artillery began firing at us. Our battery returned the fire. We of the infantry lay down so as not to catch any more of the shot and shell than we could help. It was said there were 700 dead and wounded in our front. I know it looked as if we could walk over men without putting foot to the ground.

After our battery opened on them, the enemy scattered. Then we were ordered to do a thing that I thought then, and think now, was a foolish, foolhardy thing. Our music struck up, and with arms at “shoulder” we marched in a solid square out into that open field, the bands playing Be- hold the Conquering Hero Comes. There we stood at “rest,” supposing all the time that the Rebs would open fire, as we were in plain view of them.

We lay down, expecting we were now safe for the rest of the day. Scott was marching up and down in front of us, declaiming some funny piece to amuse us, when the Rebs began to shell us. Scott kept on declaiming, and the boys kept on laughing. Then, with a heavy shock, a big shell struck within ten feet in front of our company and buried itself in the ground. We just held our breaths, expect- ing it to explode. Scott threw himself on the ground. I flattened myself out on the ground, until I seemed to have made a hole in it. May- be you can imagine what the suspense was, waiting for some of us to be killed. Of course, all this happened quicker than you can read it. After perhaps a minute Mark Naper lifted his head, his eyes big as saucers, and said, “Why don’t the — thing bust?” That made us laugh. As far as I know, the shell never did explode.

We became so used to noise — the firing of guns and can- non, the yelling and cursing of teamsters and artillerymen, and the blaring of bugles — that when permitted we would lay down and go to sleep amid it all and only our brigade bugle call would rouse us.

On the famous march from Atlanta to the sea we traveled light. Three days’ rations were issued to each man. Fifteen days’ rations for each man was put into wagons. We were ordered to form forage squads and to live off the country or go hungry. We did both at times, often having nothing to eat for 24 hours. Commonly our rations consisted of sowbelly — fat salt pork — and hardtack. We got four large hardtacks — crackers so dry as to resist all action of the weather — as a day’s ration. We had coffee, too, and sometimes sugar. At times we would draw what was called desiccated vegetables, a mixture of peas, beans, cabbage, turnips, carrots, onions, and beets, with grass to hold everything together, and dried and pressed. A piece an inch square would swell and swell into all the soup a man could eat. It was not to be despised. Our coffee generally was parched. Sometimes we would boil the berries whole, save and dry them later and trade them to the natives for corn bread, milk or butter. It was a fair exchange for some of the pies we got. Nobody but a soldier or an ostrich could digest them.

During this time we could draw no clothing, and ours was nearly worn out and did not pretend to cover our nakedness. I have foraged women’s shoes and stockings and worn them too. The mountain women had good-sized feet and wore heavy calf shoes, so I did not do so bad.

Our orders, while out foraging, were to capture all Confederate soldiers, seize all horses, burn all cotton and all Rebel government stores, but not to molest any citizens who remained at home and to respect all private property except for horses, mules and forage for man and beast. As far as I know, the order was respected.

Many times in Georgia we and the Rebs — after skirmishing and shooting at each other all day — arranged our own private truces. Once we stripped off, swam to a sand bar in the middle of a little river and traded our coffee for their tobacco. When we lay for a time along the Chattahoochee River, we agreed not to fire at each other except by officers’ orders and, if such orders were given, to notify the other side before firing. We told each other across the river, about 20 or 30 rods wide, that if we did kill a man once in a while it would have no effect on the war as a whole, that it was all nonsense.

One evening just before sundown, as both sides were taking it easy, a Rebel officer galloped up on his horse and began cursing and swearing at his men for not shooting the d—n Yankees. “Talking with them, are you?” he yelled. “Begin firing and shoot the hell out of them.”

We could hear everything he said and took up our guns. The Rebs yelled, “Hunt your holes.”

Little Charley Hapgood of our regiment, a splendid shot, says, “I’ll fix him.” We all stood watching as Charley fired. The Rebel officer threw up his arms and fell dead.

We cheered and cheered and called, “Say, Johnny, is it time to hunt our holes yet?” and they said, “No, he was a damn fool anyway and deserved what he got.”

Later on I also had some trouble with one of our own officers, a general, no less. In our corps, the Twentieth, one division consisted in part of Eastern troops under Maj. Gen. John W. Geary of Pennsylvania. Geary was a martinet, much stiffer with his boys than we of the West could stand. He frequently threatened to arrest us while foraging and confiscate our forage. He was cruel, too, in exacting full discipline of his men. I have many times on the march passed his camp and seen men with a cord tied around their thumbs, standing on tiptoe with their arms stretched above their heads and their thumbs tied to the limb of a tree. It was an ugly sight, and more than once our boys cut the men down.

My run-in with Geary came one morning when I was walking back from the advance guard with a message. About halfway, Geary and his adjutant rode up. I saluted and stepped aside to let them pass. Halting his horse, he asked, “What in hell and damnation are you doing here?” I told him. “You’re a damned liar, you are skulking,” he replied. “About face and go with us until we meet your command.” I told him that he was mistaken, that I was obeying orders already and could not obey him. He swore he would cut me down and drew his sword. His adjutant moved to draw a pistol.

I cocked my gun and said, “Sew, or I’ll kill you both where you are.” I then repeated my story and begged their pardon for my conduct.

Geary remarked to the adjutant, “I expect we were too fast,” and to me, “I believe you, and I am sorry for my anger.” He went one way, and I went the other.

Picket or guard duty was fun for the boys, for they not only got away from camp but had a chance to catch up officers. One time I stood sentry close to the enemy lines. Oh, how it rained! The mud was half knee-deep. Just as the morning began to get gray, I saw out in front of us a man slipping along from tree to tree, followed by several more. He passed post after post until he came to mine. He had on an old slouch hat, pulled well down over his face to keep the rain off, and a rubber blanket, high boots with spurs and a sword at his side. Well, I says to myself, it is Sherman, but he must come in like anybody else.

As he got in front of me, I called to halt him. At first he paid no attention, so I cocked my gun and says, “Halt! Come in or I’ll fire.”

Sherman and his staff put their hands up and came up to me, all of them. Sherman shook hands and said this was the only post but one to halt him, and that other posts let him go as soon as they knew him. I said, “Our orders were to halt everything that moved in our front.”

He said, “You did right,” and said he was out examining the lines. When he left, I saluted him, and he and his companions returned the salute. He was a nice general. Wherever he went, the boys would give three cheers for “Old Tecump” or for “Billy T,” and he would grin and wave his hat to us. He could joke too. There were lots of foreigners — Germans, Irish and others — among our troops. Once when the Rebs stopped us near Atlanta, I heard that Sher- man shouted command-like, “Attention, creation! Forward by nations and flank them!”

While marching through the public square at Smithfield, North Carolina, we saw Sherman seated on a big block. Behind him was an elevated platform with a rail, and in the center of it a tall and stout post with rings and cords attached. The platform was the auctioneer’s stand where he knocked off slaves to the highest bidder. The post was the whipping post. Just as we came up to Sherman, he cast his eyes toward this platform and waved his hand toward it. In just one minute, we had it torn down. Someone struck a match, and the whipping post was no more.

As we hurried by him, we asked, “How’s that, general?”

He grinned and said, “Good job.”

In Richmond a large section had been burned, and for blocks and blocks the weeds and grass were growing where houses had been and between paving stones. It was a picture of desolation and ruin. The country beyond Richmond was so bare that orders were very strict against foraging, but the boys had innumerable excuses when found with a pig, goose, or chicken. The goose tried to bite, so had to be killed. The chickens crowed to the tune of Dixie, so had their necks wrung. Pigs squealed for Jeff Davis, and soldiers could not stand that!

Then we marched for hours across the field of the Battle of the Wilderness, which lasted for days. We could tell by the graves how far charges went, and where Rebels and Yankees had stood. The dead were barely buried. It seems terrible to think of it now, but the boys would kick a skull out of the way as indifferently as if it had been a stone. Some would pick up a skull with a bullet hole in it and speculate about it.

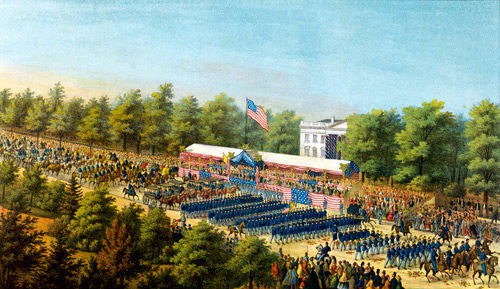

At the end of it all the Army of the Potomac, in white gloves and collars, with new uniforms, with their buckles and eagles bright as stars, paraded through Washington past the grandstand which contained President Johnson, generals Grant and Sherman and many others. The next day we of the West had our parade. We had been ordered to draw new uniforms. At the last moment our regiment packed them away. Instead of smart knapsacks, we had our blankets rolled up and hanging over our shoulders. We were so tanned we looked almost black, with worn uniforms and all kinds of hats, but our guns were always clean and bright. There was not a collar or pair of white gloves among a thousand men. There was as great a contrast between us and the “feather-bed soldiers” as possible. But when we halted in front of the reviewing stand, everybody cheered like mad. We stood there, as indifferent as an old maid to the voice of flattery.

“How We Marched Through Georgia,” May 20, 1961

Have Americans Ruined Memorial Day?

Memorial Day has always had a problem.

Originally called Decoration Day, it started after the Civil War as a day set aside for Americans to place floral tributes on the graves of soldiers who had died serving their country. May was chosen because it was the month when many flowers were in bloom.

Decoration Day was always observed on May 30, which often fell on a weekday. Many had to take time out of their work schedules to visit a cemetery and pay tribute to America’s heroes.

But in 1968, with the name officially changed to Memorial Day, it was moved to the last Monday in May. It became one of five national holidays that, for the sake of convenience, was tacked onto a weekend.

Had Memorial Day been set in another, cooler month or had it not created a three-day weekend, its purpose might be better remembered. But it occurs just as Americans are ready to start celebrating summer. It is the return of the “outdoor season” and is strongly associated with picnics and barbecues. For the young, its meaning can get lost in the euphoria of the end of school.

The concern that the true purpose of Memorial Day has been lost is not a new one. Americans have been complaining for over a century that the day barely honors the fallen.

In 1872, Eliza Connor, a regular contributor to the Post who wrote under the pseudonym “Zig,” observed that Americans were using Decoration Day like a second Fourth of July. Though the Civil War was just a few years in the past, the purpose of the day was already being obscured by parades, brass bands, fireworks, and, worst of all, politics.

Decoration Day

Zig’s Letters

June 29, 1872Decoration Day, May 30, … ought to be a day sacred to all the holy, gentle feelings of mortal nature, sacred to sweet memories and sweeter hopes. A day when strife, malice, envy, and all evil are banished utterly from our hearts, when, for one day, good should fill men’s breasts wholly. I think that is what those who are gone would wish.

But I fear there isn’t very much reverence for the sacred, gentle emotions in us Americans. There isn’t in us very much reverence for anything, I think, or else we should never turn a day set apart for visiting the graves of our dead friends into a Fourth of July. There is that which is absolutely shocking about the way Decoration Day is coming to be observed. I don’t know how it is elsewhere, but here among us such an infernal hullabaloo was kept up all day that you couldn’t hear your own ears. [Zig wrote from Indianapolis, Indiana.]

At break of day the demonish din began. With the very first peep of light, aye, before it, we were affrighted from our slumbers by a thundering shot-gun cannonade right under our very windows. We bolted out of bed as if we ourselves had been shot, wondering in our scared bewilderment, if a New York mob wasn’t coming, or indeed whether Old Nick himself wasn’t after us.

The shot-gun cannonading increased as the morning wore on, every minute being nearer, clearer, deadlier than before. What on earth could it mean? And it was not for two full hours that I remembered, with a blush for my fellow countrymen, that it was the thirtieth of May — a day sacred to the memory of the blessed dead. Later on in the day, they had processions of policemen, secret societies, and brass bands of music, and processions of citizens in carriages, and ladies and citizens on foot, and the Mayor and Council, and wagon loads of young ones, and that sort of thing, for all the world like a Fourth of July. I don’t particularly remember to have heard any popping of torpedoes or explosions of shooting crackers, but I haven’t a doubt that next year they will go off lively, and I dare say fireworks will be added in the evening, and they will have special Decoration Day plays at the theatre, with dead soldiers in the show. It will be very nice, and just like the progressive spirit of Young America.

But the most sacrilegious feature, the most abominably disgusting feature about Decoration Day is that the office-seekers have turned it into a day for electioneering and the firing-off of their accursed political popgunnery. Some despicable ward politician —and there never was a ward politician who wasn’t despicable — invariably gets hoist of the occasion, and spouts his small buncombe at folks till they are sick. It is simply outrageous. The man who played cards on his grandmother’s coffin was guilty of no greater desecration.

I wonder how the dead soldiers like it.

Every year thousands and thousands of dollars are spent on Decoration Day. It is a day for pomp and vanity and show. Foolish people vie with each other in the number and variety of costly flowers which they purchase, much the same as horse-fanciers seek to out-do each other in the matter of fast trotters.

There has been money enough spent in this foolish rivalry to feed, clothe, and educate every destitute soldier’s orphan in the land. And if departed souls ever can behold the scenes of this life again, I know that many and many a brave man who laid down his life for his country, looks sorrowfully upon the roses which garland his grave on Decoration Day. Because his fellow countrymen and women cover his senseless clay with flowers, and leave the children whom he loved to become outcasts and street Arabs. It is really pitiful to remember how much some of the soldier’s children have lost. And if the money which is thrown away every year on useless pomp and show, were spent to educate the orphan children, to train them to noble, virtuous lives, then our beloved soldiers’ graves would be decked with immortal flowers, and Decoration Day would be crowned with garlands which would grow greener with each succeeding year. Again, I think that is what those who are gone would wish.

ZIG.

On this Memorial Day, some Americans will forget to honor the men and women who died in the country’s service. Others will remember but be unable to decorate a military grave. They can still honor the fallen by keeping a sense of gratitude for what the price our soldiers paid to protect our priceless legacy: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Featured image: Decoration Day, 1917. (Library of Congress)

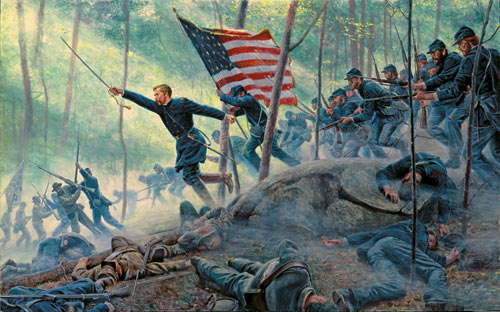

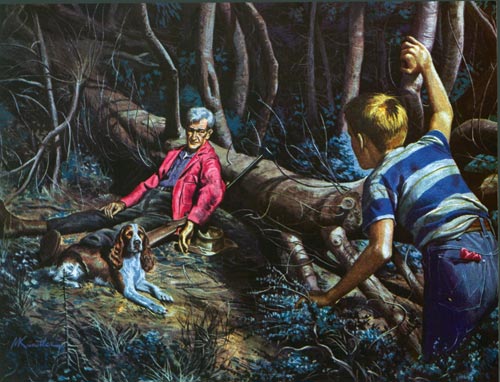

Mort Künstler on Painting the American Adventure

Mort Künstler is revered today for his intricately detailed and painstakingly researched historical paintings, but those works tell only part of the story of his extraordinary 60–year career. This is a man who loves to paint, or rather lives to paint, a man who will tell you he gets as much satisfaction creating an ad for household soap as crafting a fine-art portrait of Lee and Grant at Appomattox. And indeed, before turning his attention to great moments in American history, Künstler took on all commissions, painting innumerable magazine illustrations — including for the Post — as well as advertisements, book covers, movie posters, even model kit box covers and stamps. In fact, if you think you don’t know his work, well, it’s almost certain that you’ve seen it in some form somewhere.

Künstler was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927. His parents recognized his talent at an early age and bought him art supplies and drawing lessons before he started school. Sickly as a young boy, he began exercising and developed into a talented athlete, becoming the first four-time letterman at Brooklyn College. After three years, he transferred to UCLA on a basketball scholarship, but soon returned home when his father suffered a heart attack. Back in New York, he enrolled in the Pratt Institute.

After graduating from Pratt with a certificate in illustration in 1950, Künstler quickly found work. Simply put, his artwork sold magazines, and publishers kept coming back for more.

Even as he was composing lurid covers for men’s adventure magazines (a soldier blasting his way through a pack of rabid wolves with a machine gun; a furious grizzly hoisting a hunter in its jaws), Künstler showed a knack for engaging the viewer in a human way reminiscent of Norman Rockwell. “Mort has the ability to express the power of the individual, often at a moment of triumph, confusion, or humor,” says Martin Mahoney, director of collections and exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum.

A 1966 assignment from National Geographic on the early history of the town of St. Augustine and another one on the discovery of San Francisco Bay would be game changers for the artist.

Employing his innate sense of drama, he brought these historic moments to life. Soon, he was painting scenes from the Civil War. Mahoney describes his own excitement when, as a boy, he was given a copy of Künstler’s Images of the Civil War. In the introduction to a major exhibition of Künstler’s work that Mahoney curated at the Norman Rockwell Museum, he describes the book as “a tipping point. … Suddenly the events of the era crystallized, and historical figures that lived, breathed, and died during this traumatic period of our country’s history became real.”

These historical paintings also reveal Künstler’s evolution as an artist, says Mahoney. “You see that he’s capturing that moment of excitement, which comes from adventure illustration, but he really began to develop his research chops as well as his artistic ones. He’s getting the saddles right; he’s getting the way the mule is loaded correctly; he’s got the way the cloaks will fall if you’re riding a horse.”

At 89, Künstler has no intention of slowing down. His paintings today fetch up to $250,000, and many adorn museum walls and are featured in traveling exhibitions, including a new one — Mort Künstler: The New Nation — at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York, running through April 2. I was able to squeeze in a phone call during a brief break in his busy work schedule.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, The Mud March © 2005 Mort Künstler, Inc.

Steven Slon: You’re a master of what’s often called narrative art — which is a fancy word for illustration. And you certainly are a rarity in the sense that most successful artists today, the ones whose work is in museums, tend to be abstract artists. But you, like Norman Rockwell, have always stayed true to the kind of art that tells a story.

Mort Künstler: I don’t know if you know this, but I own seven Rockwells.

SS: I did read that you were a collector and a fan.