College of Dreams: Creating a Bright Future for ALL Students

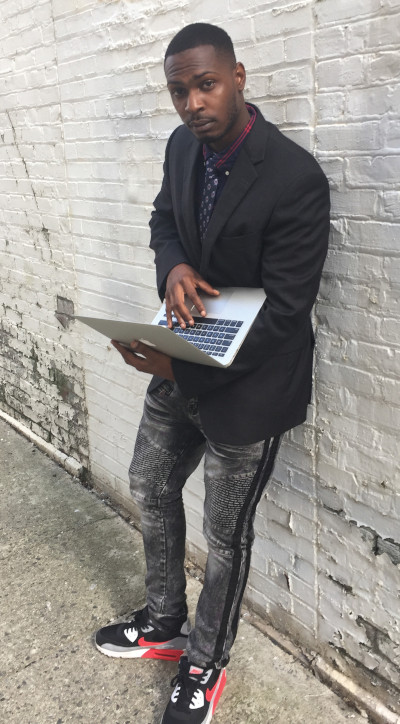

Where Princeton Nelson came from, a college education wasn’t just at the outer edges of possibility, it was beyond imagination. Yet here he was, a proud member of the class of 2018 at Georgia State University, a computer science major with a cap and gown and a more than respectable 3.3 GPA, taking his place at a crowded indoor commencement ceremony along with the Atlanta Fife Band and professors in gowns of many colors and a cascade of balloons in Panther blue and white that tumbled from the ceiling like confetti.

He, too, got to shake hands with the university president, Mark Becker, whose welcoming remarks had invoked “the magical power of thinking big.” He, too, got to hug his fellow graduates, many of them seven or eight years younger than him. He, too, could bask in the pride of his relatives, none more amazed or delighted than the grandmother who had thrown him out as a teenager because he’d been too unruly to handle.

Princeton Nelson came from nothing, and he understood at an early age that it would be up to him to carve a path to something better.

Nelson came from nothing, and he understood at an early age that it would be up to him to carve a path to something better, because nobody else was going to do it for him. Even when he slipped — and he slipped a lot — he knew the choices he made could mean the difference between life and death. He was born in an Iowa prison, the child of two parents convicted of drug dealing at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic.

Mostly, he was raised by his grandmother, Loretta, who did her best to raise Nelson and three siblings on an assembly worker’s salary in a small red house in suburban Chicago. Nelson’s mother was in no state to take him even when she got out of prison. She fell back into the drug underworld and, months after her release, was found shot to death in an abandoned building on Chicago’s South Side.

Loretta moved Princeton and his siblings to Atlanta for a fresh start, but there was little she could do to make up for what he had lost — or never had. By sixth grade, he was attending an institution for children with severe emotional and behavioral problems. His grades yo-yoed, he bounced in and out of special schools, and he barely graduated from high school.

Turning himself around was a long and painful process. For years, he worked in warehouses and smoked weed and gave little thought to where his life was going. Still, he hated the feeling that he was a disappointment to his grandmother. He signed himself up at Atlanta Technical College, thinking at first that he’d train to be a barber. Then it dawned on him that as long as he was taking out loans he’d be better off working toward an academic degree, not just a trade qualification. As it happened, there was a community college, Atlanta Metropolitan, right across the street, and he wandered over one day to enroll as a music major. He’d always enjoyed creating music beats on his grandmother’s computer. Why not see where it could take him?

As he stood in line to register, he noticed a chart listing the professional fields expected to be most in demand in the Atlanta area by 2020, and his eyes fell on the words “computer science.” “What did I have next to me in my grandmother’s house this whole time?” he said. “A computer!” It wasn’t just music beats that he’d created. He’d also worked on MySpace pages and video games, never thinking there could be a future in it. But now, apparently, there was. “It was a flash of light,” he said, “I’m thinking, I’m a computer science major. That’s my calling.”

Nelson’s grades were strong enough to earn him an associate’s degree in computer science in two years. But his life, like that of almost every lower-income college student, remained precarious at best, a constant battle for time and money. When his aunt and uncle bought the house where he and his grandmother were living, one of the first things they did was evict him, saying they were concerned about his pot use and the shortcuts they suspected he was taking to make ends meet. Before he could think of pursuing his studies further, he had to deal with the realities of homelessness. For two weeks he slept on the concrete floor of a bus station so he could bump up his savings from a job flipping burgers and buy himself a car. Once he had his Volkswagen Jetta, he signed on as an Uber driver. Soon he had a third job, as a security guard. Three days a week he stayed in a hotel to enjoy a bed and a hot shower; the other four days he parked overnight at a 24-hour gas station or outside a Kroger’s supermarket where the lights and security cameras made it less likely he’d be robbed, or worse.

He was still homeless when he started at Georgia State in the fall of 2016, but starting in his second year, he joined forces with two of his fellow computer science majors and started designing websites as a side gig. That made him hopeful enough to move out of his car and put all his savings into a deposit for an apartment. It was touch and go at first, because the freelance design work didn’t come in as quickly as hoped, and he had to take a full-time job as a cellphone technician for two weeks to make what he needed for the next month’s rent.

To many eyes, Nelson might not have looked like college material at all. Georgia State, though, was starting to enjoy a national reputation for its pioneering work in retaining and graduating large numbers of students much like him — poor, Black, and struggling to make it as the first in their family to attend college. The university understood his need for extra support. When it became apparent he was depressed because of the financial pressures, he was encouraged to see a campus therapist, the first counselor he’d ever talked to. Twice when his money was running dangerously low, the university awarded him grants to help him reach the finish line.

Academics were never Nelson’s problem. Next to what he’d been through, a challenging course in math or programming held no terrors. Rather, he became fascinated by what it meant to live a normal, middle-class life and was determined to learn how to lead one himself. “I’m always thinking about where I came from. And I still feel like I’m dumb, like I’m still competing with all these college students and falling short.”

While the children of the rich and the very rich continue to enjoy expanding opportunities to pursue a university education, the prospects for everyone else have either stagnated or narrowed dramatically.

It’s a feeling that did not go away even after he graduated and headed toward his first full-time job as a software engineer for Infosys. “That’s the difference between me and those Harvard kids,” he said. “If people like me fail, we’re going to fail our life.”

Nelson was far from the only member of Georgia State’s class of 2018 with a tale of adversity and triumph. Greyson Walldorff, who had been forced to give up an athletic scholarship in his sophomore year because of a concussion, stayed afloat and completed a business degree by starting a landscaping company that grew over time to five employees and more than a hundred clients. Larry Felton Johnson completed a journalism degree on his fourth try, 49 years after he first enrolled, thanks to a state program that offered free tuition to students over the age of 62.

Then there was Savannah Torrance, who had almost dropped out in her freshman year because she was commuting 60 miles each way from her mother’s house, working long shifts at a supermarket, and absolutely hating the chemistry class she thought she needed to build a career in the medical field. Thanks to some timely guidance from Georgia State’s advising center, though, she switched to speech communications, which required no chemistry, won a state merit scholarship she’d narrowly missed out of high school, and was soon thriving both in her studies and as a student orientation leader, university ambassador, and member of the student government association.

Georgia State boasts almost no success story that doesn’t include at least one moment where everything was in danger of crumbling to dust. At a school where close to 60 percent of undergraduates are poor enough to qualify for the federal Pell grant, that is just the nature of things. What is remarkable about Georgia State students is that despite the precariousness of many of their lives, they still graduate in extraordinary numbers. In 2018, more than 7,000 crossed the commencement stage, 5,000 of them to pick up a bachelor’s degree and the rest an associate’s degree from one of the university’s five community college campuses scattered around the Atlanta suburbs. That translated to a six-year graduation rate of close to 60 percent, significantly above the national average.

Georgia State’s achieved a 74 percent increase in the graduation rate over 15 years. This is not just about the lives of a few unusually tenacious and talented individuals. We are talking about a fundamental transformation, a real-time experiment in social mobility that the university has learned to perform consistently, and at scale.

How did Georgia State do it? In the wake of the 2008 recession, a new leadership team at Georgia State, acting out of economic necessity as well as moral conviction, determined that there was nothing inevitable about the failure of students who were poor, or nonwhite, or whose parents had never attended college. Rather, what held them back were barriers erected by the university itself and by the broader academic culture. Georgia State developed data to understand those barriers and to identify the inflection points where students most commonly came to a crossroads between success and failure. For years, Georgia State has graduated more African Americans than any other university in the country — not by tailoring special programs to them but by treating them like everyone else and providing support where they need it, regardless of wealth, or skin color, or any other consideration.

While the children of the rich and the very rich continue to enjoy expanding opportunities to pursue a university education, the prospects for everyone else have either stagnated or narrowed dramatically.

Once, student success was thought to be a simple combination of academic promise and hard work. Now even the pretense of that egalitarianism is gone; it’s all about money and whether your parents went to college. A study by the National Center for Education Statistics from 2000 — when things were better than they have become — found that a student in the top income quartile with at least one college-educated parent had a 68 percent chance of graduating before the age of 26, whereas a student in the bottom quartile whose parents did not go to college had a 9 percent chance.

It’s not that these staggering problems have gone unnoticed. Mostly, institutions have been at a loss to address them. Many prefer to keep their focus elsewhere — on graduate programs, on research, or on cultivating an elite class of undergraduates from that golden upper quartile. Some like to point fingers: at the shortcomings of the K–12 education system, at budget-cutting state legislatures, at a political culture that loves to hate academia and questions why students don’t invest in their own futures instead of relying on the public purse for financial aid. It has become fashionable for elite institutions to brag about the lower-income students they champion and finance, but they do this at a scale entirely dwarfed by a public university like Georgia State, which has three times as many Pell-eligible students as the entire Ivy League.

It has taken more than 20 years to come up with a more durable answer to the problem and to push back against a higher education culture that too often serves the interests of everyone but the students. The first stirrings came at a handful of public universities in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Arizona — states with rapidly growing urban populations and a hunger for economic growth that exceeded any appetite to hold back historically suppressed racial minorities. Why, administrators in these states started asking, should faculty members get to decide when to teach classes if it means students have to wait extra semesters to take courses essential to their majors? Why should students with no family history of negotiating an undergraduate degree have to figure out for themselves which classes to take, in which order?

Starting in the mid-1990s, these campuses rewrote course maps, rethought student advising, grouped freshmen together by subject area, lifted registration holds for petty library fines, and found a variety of other ways to ease the students’ path through the campus bureaucracy.

After 2008, Georgia State was able to take these ideas and turbocharge them with the analytical powers of emerging new data technologies. The incoming president, Mark Becker, was a statistician by training who understood the power of creating successful models and scaling them across tens of thousands of students. His student success guru, Tim Renick, had been a singularly gifted classroom teacher and needed no persuading that lower-income and first-generation students were worth believing in, because he’d seen over and over how they responded to his teaching and thrived.

Renick couldn’t stomach a system that knowingly sold students a bill of goods, inducing them to load themselves up with debt for a degree that at least half of them stood no chance of getting. What started as a moral imperative to graduate large numbers of traditionally underserved students has become a national rallying cry, a challenge to other institutions to ditch the old excuses and follow Georgia State’s lead.

The wonder of Georgia State rests on a simple idea: that if students are good enough to be admitted, they deserve an environment in which they can nurture their talents regardless of personal circumstances.

Georgia State’s pioneering innovations have been written up in The New York Times and discussed with fervor at hundreds of education conferences. Public universities nationally are in broad agreement that the revolution in downtown Atlanta points the way to all their futures. These breakthroughs came about thanks to the interactions of those educators who threw themselves into the work and stuck with it despite long hours and modest compensation, because they couldn’t imagine doing anything more meaningful with their lives; and of course the role played by the students, whose tenacious example and unbreakable will either inspired important changes or exemplified their life-changing benefits or, often, a bit of both.

Andrew Gumbel worked as a foreign correspondent for Reuters and the British newspapers The Guardian and The Independent. He is the author of Down for the Count, Oklahoma City, and Won’t Lose This Dream.

Copyright © 2020 by Andrew Gumbel. This excerpt originally appeared in Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: The future looks bright: GSU has gained a reputation for graduating large numbers of students who are poor, Black, and struggling. (Steve Thackston/staff photographer at Georgia State University)

Cartoons: Funny Money

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Brad Anderson

July 3, 1954

Mort Temes

May 15, 1954

Bill King

April 24, 1954

Al Johns

April 17, 1954

David Pascal

April 17, 1954

Stan Fine

April 10, 1954

Ken Duggan

April 9, 1955

Bill Mittlebeeler

December 5, 1953

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

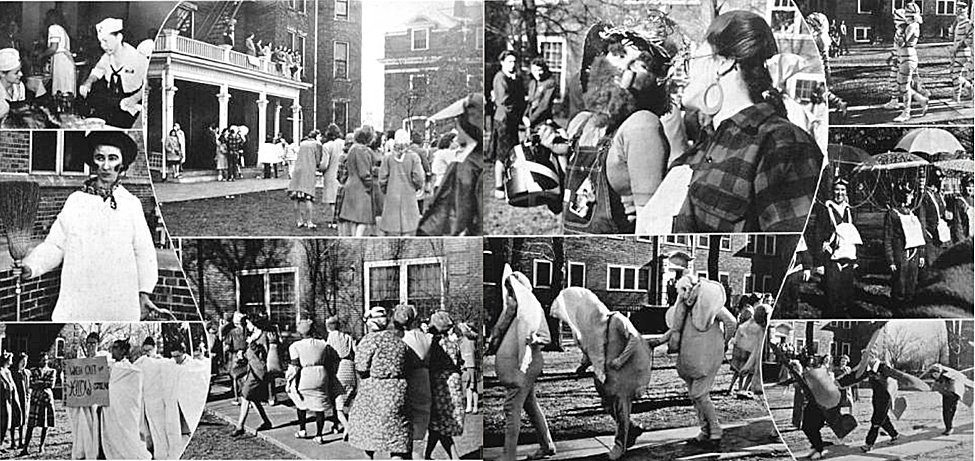

Memories of a Women’s College in 1942

Today, it’s a time capsule. A Sinatra record playing on my portable record player as I studied for an exam in U.S. History, the little known “Night We Called It A Day.” Still a favorite. There was a moon out in space/But a cloud drifted over its face/You kissed me and went on your way/The night we called it a day.

The place was my dorm room at Stephens Junior College for Women in Columbia, Missouri, in 1942.

It was a time when men weren’t allowed on dorm floors above the entry lobby except the day of arrival or departure, for hellos and goodbyes and moving trunks. That included fathers. Brothers. Fiancés. It mattered not. And it was standing policy that if you were caught (even seen) in a car with a member of the opposite sex without written proof from home that he was your brother or fiancé, you were subject to immediate and automatic expulsion.

When you went into town for dinner or over to the University of Missouri to see the latest student play, you had to sign out … and back in, a counselor at the door that would be locked (depending on your year) at 10:00 or 11:00.

My first year, my roommate was from the Lone Star State. We quickly dubbed her “Texas.” Her father had a grocery store, and her packages from home came in big, big, big boxes. One of the first things I learned in college was that Hershey bars come packaged in boxes of 24 — not a good thing for me. (One of the special offerings of Stephens College was a Diet Table, for those who could lose a few pounds while gaining a wealth of new knowledge.)

The social life of Stephens revolved around the “Blue Rooms” — areas in dorms where we gathered to smoke, because we weren’t allowed to smoke in our rooms or anywhere else on campus. The Blue Rooms also had soft drinks and various snacks, as well as light lunches.

I particularly remember my visits the Sunday afternoons following our trips to town to see the latest movie. One time, it was Now, Voyager, and when I walked into the Blue Room I frequented near my dorm it was obvious who’d also just seen the film — the girls who were lighting two cigarettes and handing one to a friend, as Paul Henreid had done in the film. One of the more famous moments in his romance with Bette Davis, handing Davis the second cigarette.

Another time, everyone was singing, “You must remember this, a kiss is just a kiss, a sigh is just a sigh ….” But not as well as Dooley Wilson in Casablanca.

I don’t remember any war movies then. But the war was a factor in my being there. Stephens was the choice my parents decided upon (principally, my mother) because I was just 16 when I graduated from high school and the war had started. She apparently foresaw that college life would no longer be a Good News movie; indeed, universities would become training centers for the U.S. Armed Services — Army and Navy Air Force pilots and bombardiers — and she liked Stephens’ approach to female education.

Its president, James Madison Wood, felt that while women were entitled to an education — equal, in principle, to that of men — they had special needs and interests. He addressed this with the creation of a group of clinics for the Stephens girls. The clinics were highly publicized, perhaps because of the novel approach or perhaps because of the nature of some of the clinics.

The Marriage Clinic drew my second year roommate, who left school to marry her hometown sweetheart, then stationed at a Naval Air Training base. There was a Budget Clinic, to which my father kept pointing me. At a Fashion Clinic, I had a formal designed for me. And a Glamour Clinic — the one that had gained the most national attention. The one to which Stephens girls would go to learn how to make the most of their physical attributes: hair, make-up, lipstick colors.

My mother, for whom the Glamour Clinic was an added attraction to the other lures of Stephens, wanted me to get an appointment shortly after classes started. But, what with one thing and another — getting textbooks, settling in to classes — I had not made an appointment. Then, word spread about those who had.

They came back with their hair cut!

If that doesn’t sound like much today, it was the kiss of death then. We wore our hair long. Mine — even with the upturned curl of an incoming wave — grazed my shoulders. No way was I going to go near a place that wanted to cut my hair! And so I resisted my mother’s increasingly persistent questions in her letters as to when I had an appointment at the Glamour Clinic. That was an important feature she’d noticed in the school catalogue. Why didn’t I take advantage of all my opportunities at Stephens?

As the time for Christmas break approached, I felt I could not go home without going to the Glamour Clinic. It meant so much to her. Could I make clear I didn’t want my hair cut? So I went to make an appointment. The only one available was a Saturday in December. I booked it, not realizing it was also the Saturday of Hell Day for sorority pledges.

We were told by our sororities what costume to prepare and wear that day. And we would march around the main part of campus after lunch in our costumes. As with all things then, World War II affected Hell Day.

My fellow pledges and I were Flying Tigers, the name of a group of American volunteers who fought the Japanese in the China Burma Theatre before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

To become a Flying Tiger in Columbia, Missouri, I went into town and bought a suit of men’s long underwear, a package of Rit dye — orange, obviously — and a packet of black crepe paper. I duly dyed the suit and sewed strips of black crepe paper to simulate stripes. I braided some of the strips of black crepe paper for the tail. I made a propeller from the cardboard at the back of a notebook pad and, later, stuck the circular center to my forehead, also front and center, the blades vertical for visibility.

On that December morning I dressed in said outfit and headed across campus to Senior Hall, where all pledges were to dine that morning. Then I returned to my room, ready to head out not to a Saturday class but my appointment at the Glamour Clinic.

I appeared in the doorway as a faculty-type lady opened up for the day. I might be there for my mother but no way was I having my hair cut. Jaw set, words as emphatic as it was in my power to make them, I said, more proclamation than statement: “I won’t let you cut my hair!”

Something about the reaction of the Glamour Clinic lady made me realize that was not my problem. The frozen smile was a clue.

The faux Flying Tiger before her was not only eye-catching for starters, I was all the more noticeably overweight in the suit of men’s long underwear dyed a Technicolor-bright orange. I bulged in all the wrong places. Corrugated cellulite comes to mind. Sometimes the bulges synchronized with my tiger stripes, sometimes not. The wet snowfall had loosened my propeller, not securely stuck to my forehead, and it fell off. When I bent to retrieve it, my tail caught on something and almost came off. I quickly secured it.

Suffice to say, I went through the routine/procedure/protocol of the Glamour Clinic, which was designed to help me learn how to make the most of my appearance, in record time.

I don’t remember a thing until the end, when the Glamour Clinic lady had me seated at one of those basins where you get your hair washed at beauty parlors. I was in the chair, tipped back, head in the big metal tray, as she talked about my eyebrows. She may have plucked one or two stragglers. I just remember she was talking about my eyebrows when a voice was heard in the doorway. I say voice because I was flat on my back and the Glamour Clinic lady had her back to the door.

“I know I’m early, but ….”

“No. No,” said the Glamour Clinic lady. “Come right in.”

It would be hard to imagine a more sincere welcome. The Glamour Clinic lady’s heartfelt Thank you! to a merciful god for her deliverance.

No need to imagine the rest. She snapped me up to a sitting position with a speed that it’s a wonder my eye balls aren’t still spinning.

When I looked to the doorway, I understood the silence that followed. Settled over the otherwise empty expanse of the Glamour Clinic.

A speechless silence.

The next appointment was having trouble getting in.

She had outdone my flying tiger. With the help of some well-shaped cardboard and gray paint, she was a battleship.

Returning to my room, I sat down at my desk, pulled out a piece of stationery, and, pen poised, began.

Dear Mother,

About my appointment at the Glamour Clinic ….

Featured image: College women playing bridge, 1942 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Safety Police: Is Free Speech Being Stifled on College Campuses?

Something is going badly wrong for American teenagers, as we can see in the statistics on depression, anxiety, and suicide. Something is going very wrong on many college campuses, as we can see in the rise in efforts to disinvite or shout down visiting speakers, and in changing norms about speech, including a recent tendency to evaluate speech in terms of safety and danger. This new culture of “safetyism” is bad for students and bad for universities.

Safety is good, of course, and keeping others safe from harm is virtuous, but virtues can become vices when carried to extremes. “Safetyism” refers to a culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people become unwilling to make trade-offs demanded by other practical and moral concerns. “Safety” trumps everything else, no matter how unlikely or trivial the potential danger. When children are raised in a culture of safetyism, which teaches them to stay “emotionally safe” while protecting them from every imaginable danger, it may set up a feedback loop: kids become more fragile and less resilient, which signals to adults that they need more protection, which then makes them even more fragile and less resilient. The end result may be similar to what happened when we tried to keep kids safe from exposure to peanuts: a widespread backfiring effect in which the “cure” turns out to be a primary cause of the disease.

When the federal Office of Education began collecting data in 1869, there were only 63,000 students enrolled in higher education institutions throughout the United States; they represented just 1 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds. Today, an estimated 20 million students are enrolled in American higher education, including roughly 40 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds. U.S. elite institutions draw substantial international enrollment, and 17 of the top 25 universities in the world are in the U.S. The enormous expansion of scope, scale, and wealth demands professionalization, specialization, and a lot of support staff.

Young people have come to believe that danger lurks everywhere even in the classroom, and even in private conversations.

Some administrative growth is necessary and sensible, but when the rate of that expansion is several times higher than the rate of faculty hiring, there are significant downsides, most obviously the increase in the cost of a college degree. A less immediately obvious downside is that goals other than academic excellence begin to take priority as universities come to resemble large corporations — a trend often bemoaned as “corporatization.” Political scientist Benjamin Ginsberg, author of the 2011 book The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters, argues that over the decades, as the administration has grown, the faculty, who used to play a major role in university governance, have ceded much of that power to non-faculty administrators. He notes that once the class of administrative specialists was established and became more distinct from the professor class, it was virtually certain to expand; administrators are more likely than professors to think that the way to solve a new campus problem is to create a new office to address the problem.

These administrators are bombarded with directives (from in-house counsel, outside risk-management professionals, the school’s public relations team, and the upper echelons of the administration) that they must limit the university’s legal liability in everything from personal injury lawsuits to wrongful termination, and from intellectual property to wrongful-death actions. This is one reason they are so keen to regulate what students do and say.

Two categories of First Amendment cases on campus encourage this kind of thinking quite directly: overreaction and overregulation.

Overreaction and overregulation are usually the work of people within bureaucratic structures who have developed a mindset commonly known as CYA (Cover Your Ass). They know they can be held responsible for any problem that arises on their watch, especially if they took no action to prevent it, so they often adopt a defensive stance. In their minds, overreacting is better than underreacting, overregulating is better than underregulating, and caution is better than courage. This attitude reinforces the safetyism mindset that many students learn in childhood.

It certainly did not help that today’s college students were raised in the fearful years after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Ever since that awful day, the U.S. government has been telling us: “If you see something, say something.” Young people have come to believe that danger lurks everywhere, even in the classroom, and even in private conversations. Everyone must be vigilant and report threats to the authorities. At New York University in 2016, for example, administrators placed signs in the restrooms outlining how to report one another anonymously if they experience “bias, discrimination, or harassment,” including by calling a “Bias Response Line.”

Of course, there should be an easy way to report cases of true harassment and employment discrimination; such actions are immoral and unlawful. But bias alone is not harassment or discrimination. The term is not defined on the NYU Bias Response website, but psychological experiments have consistently shown that to be human is to have biases. We are biased toward ourselves and our in groups, toward attractive people, toward people who have done us favors, and even toward people who share our name or birthday. Presumably the administrators running the Bias Response Line are most interested in negative biases based on identity categories, such as race, gender, and sexual orientation. But given the high levels of concept creep on university campuses and the widespread idea that micro-aggressions are ubiquitous and dangerous, there are sure to be some students who have a very low threshold for detecting bias in others and attributing ambiguous statements to prejudice.

It becomes more difficult to develop a sense of trust between professors and students in such an environment. The Bias Response Line allows students to report a professor for something said or shown even before the lecture has ended. Many professors now say that they are “teaching on tenterhooks” or “walking on eggshells,” which means that fewer of them are willing to try anything provocative in the classroom — or cover important but difficult course material.

To show just one example of how bias response systems discourage risk-taking: University of Northern Colorado adjunct professor Mike Jensen was called to multiple meetings after a single student filed a “Bias Incident Report” following a discussion of controversial topics in a first-year writing class. The first reading assigned in the class was our Atlantic article, “The Coddling of the American Mind.” The professor asked the class to read the article and then engage in a discussion of a controversial topic, to be chosen by the class. The topic that the students chose was transgender issues. (One of the biggest stories that semester had been the revelation of Caitlyn Jenner’s identity as a trans woman.) Jensen suggested that students read an article about parents objecting to a transgender high school student using the girls’ locker room. He explained that although most of the students might not agree with these skeptical views, in academia, grappling with difficult and controversial perspectives is expected, so it was important that even these viewpoints be discussed. Jensen later recalled the conversation as “a very nice discussion of seeing other perspectives.” He was surprised when he learned that a student had filed a Bias Incident Report against him. He was advised to avoid the topic of transgender issues for the rest of the semester and was ultimately not rehired.

The bureaucratic innovation of “bias response” tools may be well intended, but they can have the unintended negative effect of creating an “us versus them” campus climate that results in hyper-vigilance and reduced trust. Some professors end up concluding that it isn’t worth the risk of having to appear before a bureaucratic panel, so it’s better to just eliminate any material from the syllabus or lecture that could lead to a complaint. Then, as more and more professors shy away from potentially provocative materials and discussion topics, their students miss out on opportunities to develop intellectual anti-fragility. As a result, they may come to find even more material offensive and require even more protection.

Universities have an important moral and legal duty to prevent harassment on campus. What counts as harassment, however, has changed quite a lot in recent years. For example, consider the case in which a student who worked as a janitor at his college was sanctioned because he was seen reading a book called Notre Dame vs. the Klan: How the Fighting Irish Defeated the Ku Klux Klan, a book that celebrates the defeat of the Klan when they marched on Notre Dame in the 1920s. (The image on the cover was upsetting to the two people who reported him.) Lowering the bar that far trivializes the real harm that true harassment can do — and frequently does — to students’ education. The purpose of these laws is to protect students from unlawful acts, not to empower censors.

The best example of how expanded notions of harassment have come to threaten free speech and academic freedom is the case of Northwestern University professor Laura Kipnis. In a May 2015 Chronicle of Higher Education essay, Kipnis criticized what she saw as “sexual paranoia” on her campus, arising from changing attitudes toward sex and new ideas in feminism that she found disempowering. She wrote:

The feminism I identified with as a student stressed independence and resilience. In the intervening years, the climate of sanctimony about student vulnerability has grown too thick to penetrate; no one dares question it lest you’re labeled antifeminist.

Kipnis’s essay criticized Northwestern’s sexual misconduct policies — in particular, the prohibition on romantic relationships between adult students and faculty or staff. After her article was published, Kipnis was the target of protests from student activists, who carried mattresses across campus and demanded that the administration condemn the article. Then two graduate students filed a complaint against Kipnis, claiming that her article created a hostile environment. This resulted in a secret investigation of Kipnis that lasted 72 days. When she wrote a book about her experience, she was subjected to yet another investigation, this time stemming from complaints by four Northwestern faculty members and six graduate students, who claimed that her book’s discussion of false sexual misconduct accusations violated the university’s policies on retaliation and sexual harassment. This second investigation lasted a month. She was asked to respond to more than 80 written questions about her book and to turn over her source material. While both of these investigations were eventually dropped, from beginning to end, the process took more than two years. Kipnis noted after her ordeal:

My sense was that all of these protections were not making people less vulnerable, they were making people more vulnerable. …[Students are] going to be impeded when they leave university and go out into the world, and nobody is going to protect them from the multitudes of injuries and slights and that kind of thing that we all have to deal with in the course of daily life.

In sum, administrators generally have good intentions; they are trying to protect the university and its students. But good intentions sometimes lead to policies that are bad for students. Some of the regulations promulgated by administrators restrict freedom of speech, often with highly subjective definitions of key concepts. These rules contribute to an attitude on campus that chills speech, in part by suggesting that freedom of speech can or should be restricted because of some students’ emotional discomfort.

As far as we can tell from private conversations, most university presidents reject the culture of safetyism. They know it is bad for students and bad for free inquiry, but they find it politically difficult to say so publicly. From our conversations with students, we believe that most high school and college students are not fragile, they are not “snowflakes,” and they are not afraid of ideas. So if a small group of universities is able to develop a different sort of academic culture — one that finds ways to make students from all identity groups feel welcome without using the divisive methods that seem to be backfiring on so many campuses — we think that market forces will take care of the rest. There will be a growing recognition across the country that safetyism is dangerous and that it is stunting our children’s development.

If we can educate the next generation more wisely, they will be stronger, richer, more virtuous — and even safer.

Jonathan Haidt is a social and cultural psychologist at NYU’s Stern School of Business and author of The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Greg Lukianoff is a lawyer, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and author of Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate.

This article is featured in the September/October 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: SEPS/Shutterstock.com

What’s the Matter with College?

You won’t get many people interested in discussing “the problems of higher education” until you bring up the trillion dollars. That’s the amount that America’s students now owe on their college tuition.

It’s hard to comprehend how much money $1,000,000,000,000 is. Consider this: It’s more than twice the amount, adjusted for inflation, that America paid to build its vast interstate highway system.

That’s a lot of money to repay. And with today’s sluggish economy and unemployment, more than one economist is losing sleep over whether we’ll ever clear that debt.

It’s no surprise that higher education is starting to draw the same amount of media attention, and criticism, as other big businesses. Critics are now challenging college’s admission policies, the merit of high-prestige universities, the need for traditional college lecture, and, of course, the cost.

Criticizing higher education is nothing new. Back in 1920, a Post article entitled “What a Man Loses in Going to College,” questioned whether higher education wasn’t a handicap to young men and women. “The average college man [loses] association with older people and that intimate contact with concrete issues which are absolutely essential in making a man out of boy stuff,” wrote E. Davenport.

“Instead of thinking men’s thoughts about a world during his most formative years, [the student] becomes engrossed in student activities, which have about as much connection with the real world as a wart on the end of the nose has with vision; it may obscure but it cannot illuminate.”

The author also claimed that young men, after spending four years among a juvenile cohort, became apathetic, vain, egotistical, argumentative, unreliable, and addicted to slang.

The Post editors also held a low opinion of college training. In a 1923 editorial, editors argued that a four-year degree could be earned in half the time if only students were taught a capacity for drudgery and self-discipline. Instead, colleges bred effete snobs. “We see thousands of young men turned out of college who have never learned how to work, who would scorn to yield to the obligation to do any kind of manual labor other than golf or tennis.”

By 1927, Albert W. Atwood claimed colleges were lowering their standards to admit mediocre and marginally intelligent scholars. He quoted criticism from the Association of University Professors, which sounds as if it could be written today: “When a university numbers its students by the thousands and the tens of thousands, when it admits almost anybody and teaches almost anything, when its classrooms are manned, as is inevitable, by inferior teachers, whenever endowment or appropriation must be sought in a vain effort to keep pace with its numerical growth, when each tries to outstrip its rivals in the externals and trappings of education, then the very character of the university is bound to change for the worse.”

In 1938, Dr. Robert M. Hutchins, the University of Chicago’s president, added his criticism. In “Why Go to College?” he admitted that higher education was often used as a dumping ground for young people. It was where some parent sent their children to get them out of the house for four years, and where young men and women went to avoid adulthood and responsibility.

Twenty years later, a journalism professor at the University of Indiana claimed colleges had become little more than marriage mills and fun factories. In “Are We Making a Playground Out of College?” Jerome Ellison wrote that colleges had developed a “Second Curriculum is that odd mixture of status hunger, voodoo, tradition, lust, stereotyped dissipation, love, solid achievement, and plain good fun sometimes called ‘college life.’ It drives a high proportion of our students through college chronically short of sleep, behind in their work, and uncertain of the exact score in any department of life.”

In 1965, Dr. Hutchins returned to the Post, this time declaring “Colleges Are Obsolete.” Higher education, he wrote, had become an industry concerned with numbers, not values. Colleges were only concerned with helping students amass the right number of semester hours for graduation. They couldn’t help students become more intelligent because they were no longer intellectual communities “thinking together about important things.” Instead, the campus had become just a collection of isolated specialties. “The student is never compelled to put together what the specialists have told him, because he is examined course by course by the teacher who taught the course.”

Hutchins’ article touches on the ultimate question of college: “Do our colleges help their students become more intelligent? The answer is, on the whole, no.”

Americans expect a college education to do something important, valuable, and lasting for a student. It’s difficult to assess whether a student is more intelligent after graduation. Let’s consider the value of college by a more practical measure: How much more can a graduate earn?

By this standard, college is still doing its job. Recent labor statistics from 2013 show that average Americans earned almost twice as much per hour if they had a four-year degree.

However, every college student must still individually solve the following problem: Does this earning advantage, extended over a 20-year career exceed the investment of four years and a pre-interest cash value of $18,000 to $46,000?

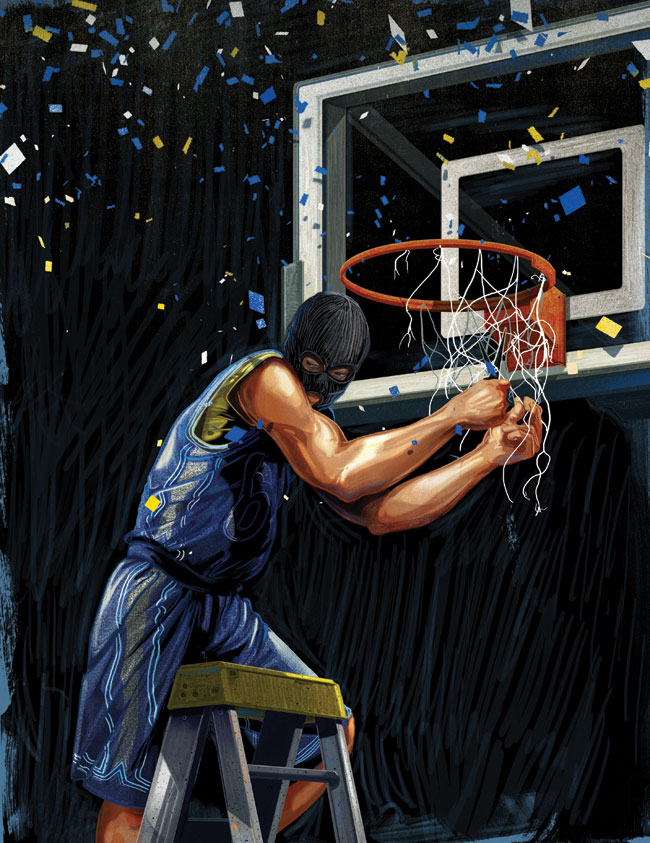

Cheating in College Sports

You can bet on it: Where there’s sports, there’s gambling. And where there is gambling, frequently there is cheating. In just one of the most recent scandals, former University of San Diego basketball star Brandon Johnson and seven others were convicted of “altering” games and sent to federal prison: Johnson was sentenced to six months in a federal facility.

Gambling on collegiate sports, an estimated $100 billion-a-year industry, is increasing every year, according to Albert Figone, author of Cheating the Spread: Gamblers, Point Shavers, and Game Fixers in College Football and Basketball. The problem of cheating is exacerbated by the increasing commercialization of collegiate sports and the huge amounts of money made by universities at the expense of underpaid student players. Case in point: Texas, the number one earner, generated in excess of $163 million from its sports programs in 2012.

With millions of dollars swirling around them, some college athletes see themselves as pawns in a system that exploits their talents. “These high-performing athletes have been trained for over 10 years and now work for the equivalent of $8 per hour based on the value of their scholarship. Sometimes they are vulnerable to gamblers who approach them with payoffs,” says Figone.

“Fixing a college game is like shooting fish in a barrel,” says Brian Tuohy, author of The Fix is In. “You can pretty much fix any college game you want to. And it wouldn’t take a lot of money to do it.”

Most college stars will never see the pot of gold associated with an NBA contract, and they know it. “At top-ranked programs, there may be two guys on the team who will end up in the NBA,” says Tuohy. “But then you’ve got a third senior who is a starter with no hope of going pro and no prospects for earning the big bucks pros make. What if you go to him and say, ‘Hey, look, I’ll give you 10 grand a game to make sure you don’t cover the spread’?”

The spread, or point spread, is essentially a gambling handicap favoring the underdog team. Rather than a straight win-or-lose proposition, the wager becomes “Will the favorite win by more than a given number of points?” A player on a team favored to win can intentionally blow a layup or miss a free throw to “shave points” off the score so as not to beat the spread. In doing so, his team can win the game while still enabling his corrupt paymasters to win their bet on the opposing team. This kind of cheating can be difficult to discern, though it frequently leads to a certain amount of lead-footed play. According to an FBI report presented at Brandon Johnson’s trial, the athlete “was heard on electronic surveillance talking about how he wouldn’t shoot at the end of a particular game because it would have cost him $1,000.”

How widespread is cheating? Figone estimates fixing the outcome of games involves only about 1 percent of the roughly 430,000 collegiate athletes. “Although the percentage may sound small, that still means more than 4,300 college athletes may be asked to influence the outcomes of games in some way,” he says. A March 2012 NCAA survey of collegiate athletes supports his estimate. Of 23,000 student athletes, about 5 percent of Division I men’s basketball players and 2 percent of Division I men’s football players admitted to having been “contacted by outside sources to share inside information.” Around 1 percent admitted to “providing inside information to outside sources.”

Gambling is like a dark cloud enveloping college athletics. Bookies and professional gamblers hang around college campuses in order to approach players about upcoming games, and the players know exactly what’s happening, even the honest ones. “I have not talked to one college basketball player who did not know the line [point spread] on the game he was playing,” says a Las Vegas-based bookie who agreed to be interviewed on the condition of anonymity.

Still, most experts say the vast majority of players are honest. “I am sure gambling or fixing collegiate games happens five times more often than you hear about. But it’s still the exception and not the norm,” says James Whitford, head basketball coach at Ball State University and former associate head coach of the 2013 University of Arizona basketball team that went to the Sweet 16.

Certainly there is awareness at the schools that the danger of cheating is very real, and the NCAA has launched initiatives to combat corruption. For example, all teams making it to the Sweet 16 in the NCAA basketball tournament are visited by FBI agents who warn them about the risks of collaborating with gamblers.

But a few strong words and even the legal consequences of violating the rules are not enough to stop all cheating. “It’s almost a perfect storm for criminal conspiracy when you’ve got young athletes with uncertain futures and financial hardships who feel they’re not going to be hurting anybody if they shave a few points,” says David Schwartz, director of the Center for Gaming Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Learning By Degrees

Susan Andersen thought she had it all: a happy marriage to a successful businessman, two wonderful children, a nice home in one of Charlotte’s finer communities, and a thriving career. Then Susan’s life took a dramatic turn. After 22 years, her marriage fell apart, and she found herself in the chaotic world of divorced parents juggling visitation schedules and haggling over holidays.

Luckily for Susan, she could fall back on her career as a sales director for Mary Kay Cosmetics. She was great at her job, earning nine of those iconic pink Cadillacs over the course of many years with the company. But instead of just throwing herself into her work or hiding under the covers, Susan listened to her heart. She decided it was time to shake things up by focusing on other peoples’ problems.

So, Susan took a sizeable portion of her own savings (an amount she declines to reveal, conceding only that it was in the low six figures) and founded the Andersen Nontraditional Scholarship for Women’s Education and Retraining (ANSWER Scholarship) to help struggling mothers go back to school and earn their college degrees.

Susan’s endowment fulfilled a promise she had made to herself nearly three decades earlier after receiving scholarship assistance for her own college education. At the time, she vowed to find a way to pay it forward. Divorce brought that dream back into focus. “I was now a single mom, and as I looked around at other single moms, I realized many were not as fortunate and were struggling. Without an education, a mom with children is destined for poverty.”

Since 2005, the ANSWER Scholarship has awarded up to $4,000 per academic year to 17 women through Foundation for the Carolinas, a community foundation that manages Susan’s endowment fund and selects her scholarship recipients. At last count, nine women have graduated. And of those nine grads, five have opted to continue on for advanced degrees on their own.

Women who receive scholarships from Susan’s endowment must meet certain criteria: The degree must be their first, and they must go to school full time at an accredited institution in North or South Carolina. “It sounds really daunting, but we made it a full-time requirement so that women would finish in four years, not spread it out over time and maybe never finish,” says Susan. “This way, the women have an end in sight, and their children can see Mom start and finish something.”

Scholarship recipients also must be at least 25 years old, and—most importantly—they must have at least one school-age child living at home with them. Susan firmly believes that children who watch their mother work hard for a college degree will one day follow in their mom’s very large footsteps to pursue their own college dreams. “When you educate the mother, you help change the destiny of her children,” Susan says.

Marital status is not a deciding factor, although the majority of recipients have been single moms.

With full course loads, homework from demanding professors, and regular exams, college can be stressful for any student. Add in part-time or full-time jobs and the realities of parenthood—helping children with schoolwork, arranging childcare, shopping for groceries, cleaning house, cooking meals, and more—and the diploma may seem like an impossible dream. Katrina Mitchell, 35, knows all about the frustration and fatigue that moms in college suffer. With help from Susan’s ANSWER Scholarship, Katrina is close to receiving her bachelor’s degree in education from Belmont Abbey College in Belmont, North Carolina.

Becoming a teacher was an early dream for Katrina, one she abandoned for a more lucrative but less satisfying career. “I make decent money working for a broker-dealer,” she says. “But I’m not happy. I just go through the motions every day.”

This vague sense of malaise crystallized a few years back when her grandmother passed away. The loss led to some soul-searching, which, in turn, led to thoughts of teaching. “My grandmother wanted to do so many things in her life and never got the opportunity. Her sudden death made me reevaluate my life,” says Katrina.

But going back to school hasn’t been easy for this mother of a boy, 3, and a girl, 11. To make it happen, Katrina used up all of her time off from work. She often arrives at her job early and works through her lunch hour so she can be on time for class, which meets four nights a week. With support from her family—as well as a college professor selected by Susan to be Katrina’s mentor—Katrina hung in there. She left her corporate job in August to begin student teaching, and she’s glad she toughed it out. “When I was young, I didn’t have the drive and motivation to succeed, and I didn’t take school seriously. My mother never talked to me about school,” says Katrina, whose mother was only 14 when she was born. “Now, my daughter is my biggest supporter and so proud of me! She told me, ‘I’m going to work hard and go to school so you can be proud of me the way that I’m proud of you.’”

Like Katrina, Tonya Nichole Faulkner, 40, grew up in a home where college wasn’t even on the radar. Tonya wanted to break the cycle of poverty for herself and her two children. The ANSWER Scholarship fund provided the escape route. In 2008, Tonya became the first in her family to earn a college degree when she graduated magna cum laude from Queens University of Charlotte with a BA in Human and Community Services. This spring, she is set to receive an MA in Nonprofit Management from High Point University in North Carolina. Her daughter is a freshman at Queens University, thanks largely to Tonya’s positive influence. “I want my children to believe they can persevere through any obstacles to achieve their dreams,” says Tonya.

Two of Tonya’s brothers also returned to school, inspired by their sister’s drive and motivation. “They figured if a single mom could go to school full time while working two part-time jobs, then they could do it, too,” says Tonya.

Tonya hopes someday to become a philanthropist like Susan. She’s already started her own nonprofit organization, Repairing the Breach Foundation, which aims to provide assistance for people in need by closing the gaps between human service organizations and those they serve.

For her part, Susan is extraordinarily proud of the women her organization has been able to help. But she modestly brushes off praise for her efforts, reminding people that she started the ANSWER Scholarship at least in part to fill a void in her own life. “Divorce was a very sad time for me, which is why I decided to do something positive,” she says. “Helping others helped heal my pain.”