Today, it’s a time capsule. A Sinatra record playing on my portable record player as I studied for an exam in U.S. History, the little known “Night We Called It A Day.” Still a favorite. There was a moon out in space/But a cloud drifted over its face/You kissed me and went on your way/The night we called it a day.

The place was my dorm room at Stephens Junior College for Women in Columbia, Missouri, in 1942.

It was a time when men weren’t allowed on dorm floors above the entry lobby except the day of arrival or departure, for hellos and goodbyes and moving trunks. That included fathers. Brothers. Fiancés. It mattered not. And it was standing policy that if you were caught (even seen) in a car with a member of the opposite sex without written proof from home that he was your brother or fiancé, you were subject to immediate and automatic expulsion.

When you went into town for dinner or over to the University of Missouri to see the latest student play, you had to sign out … and back in, a counselor at the door that would be locked (depending on your year) at 10:00 or 11:00.

My first year, my roommate was from the Lone Star State. We quickly dubbed her “Texas.” Her father had a grocery store, and her packages from home came in big, big, big boxes. One of the first things I learned in college was that Hershey bars come packaged in boxes of 24 — not a good thing for me. (One of the special offerings of Stephens College was a Diet Table, for those who could lose a few pounds while gaining a wealth of new knowledge.)

The social life of Stephens revolved around the “Blue Rooms” — areas in dorms where we gathered to smoke, because we weren’t allowed to smoke in our rooms or anywhere else on campus. The Blue Rooms also had soft drinks and various snacks, as well as light lunches.

I particularly remember my visits the Sunday afternoons following our trips to town to see the latest movie. One time, it was Now, Voyager, and when I walked into the Blue Room I frequented near my dorm it was obvious who’d also just seen the film — the girls who were lighting two cigarettes and handing one to a friend, as Paul Henreid had done in the film. One of the more famous moments in his romance with Bette Davis, handing Davis the second cigarette.

Another time, everyone was singing, “You must remember this, a kiss is just a kiss, a sigh is just a sigh ….” But not as well as Dooley Wilson in Casablanca.

I don’t remember any war movies then. But the war was a factor in my being there. Stephens was the choice my parents decided upon (principally, my mother) because I was just 16 when I graduated from high school and the war had started. She apparently foresaw that college life would no longer be a Good News movie; indeed, universities would become training centers for the U.S. Armed Services — Army and Navy Air Force pilots and bombardiers — and she liked Stephens’ approach to female education.

Its president, James Madison Wood, felt that while women were entitled to an education — equal, in principle, to that of men — they had special needs and interests. He addressed this with the creation of a group of clinics for the Stephens girls. The clinics were highly publicized, perhaps because of the novel approach or perhaps because of the nature of some of the clinics.

The Marriage Clinic drew my second year roommate, who left school to marry her hometown sweetheart, then stationed at a Naval Air Training base. There was a Budget Clinic, to which my father kept pointing me. At a Fashion Clinic, I had a formal designed for me. And a Glamour Clinic — the one that had gained the most national attention. The one to which Stephens girls would go to learn how to make the most of their physical attributes: hair, make-up, lipstick colors.

My mother, for whom the Glamour Clinic was an added attraction to the other lures of Stephens, wanted me to get an appointment shortly after classes started. But, what with one thing and another — getting textbooks, settling in to classes — I had not made an appointment. Then, word spread about those who had.

They came back with their hair cut!

If that doesn’t sound like much today, it was the kiss of death then. We wore our hair long. Mine — even with the upturned curl of an incoming wave — grazed my shoulders. No way was I going to go near a place that wanted to cut my hair! And so I resisted my mother’s increasingly persistent questions in her letters as to when I had an appointment at the Glamour Clinic. That was an important feature she’d noticed in the school catalogue. Why didn’t I take advantage of all my opportunities at Stephens?

As the time for Christmas break approached, I felt I could not go home without going to the Glamour Clinic. It meant so much to her. Could I make clear I didn’t want my hair cut? So I went to make an appointment. The only one available was a Saturday in December. I booked it, not realizing it was also the Saturday of Hell Day for sorority pledges.

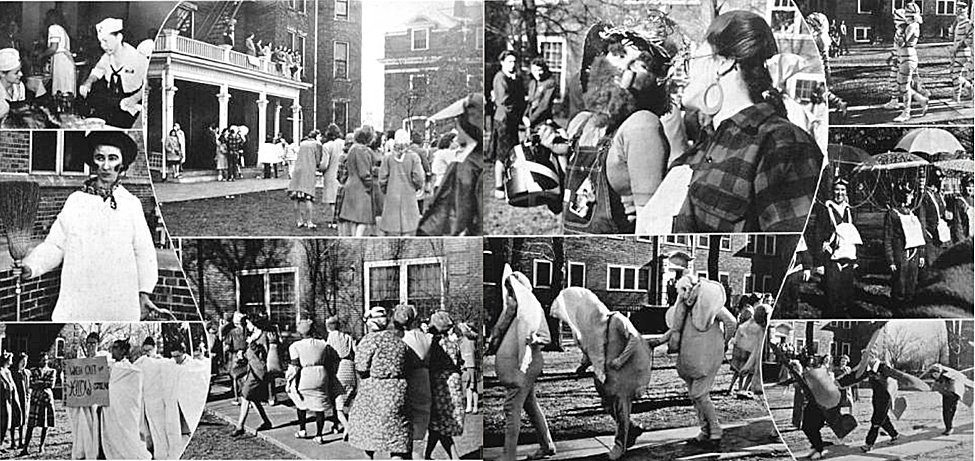

We were told by our sororities what costume to prepare and wear that day. And we would march around the main part of campus after lunch in our costumes. As with all things then, World War II affected Hell Day.

My fellow pledges and I were Flying Tigers, the name of a group of American volunteers who fought the Japanese in the China Burma Theatre before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

To become a Flying Tiger in Columbia, Missouri, I went into town and bought a suit of men’s long underwear, a package of Rit dye — orange, obviously — and a packet of black crepe paper. I duly dyed the suit and sewed strips of black crepe paper to simulate stripes. I braided some of the strips of black crepe paper for the tail. I made a propeller from the cardboard at the back of a notebook pad and, later, stuck the circular center to my forehead, also front and center, the blades vertical for visibility.

On that December morning I dressed in said outfit and headed across campus to Senior Hall, where all pledges were to dine that morning. Then I returned to my room, ready to head out not to a Saturday class but my appointment at the Glamour Clinic.

I appeared in the doorway as a faculty-type lady opened up for the day. I might be there for my mother but no way was I having my hair cut. Jaw set, words as emphatic as it was in my power to make them, I said, more proclamation than statement: “I won’t let you cut my hair!”

Something about the reaction of the Glamour Clinic lady made me realize that was not my problem. The frozen smile was a clue.

The faux Flying Tiger before her was not only eye-catching for starters, I was all the more noticeably overweight in the suit of men’s long underwear dyed a Technicolor-bright orange. I bulged in all the wrong places. Corrugated cellulite comes to mind. Sometimes the bulges synchronized with my tiger stripes, sometimes not. The wet snowfall had loosened my propeller, not securely stuck to my forehead, and it fell off. When I bent to retrieve it, my tail caught on something and almost came off. I quickly secured it.

Suffice to say, I went through the routine/procedure/protocol of the Glamour Clinic, which was designed to help me learn how to make the most of my appearance, in record time.

I don’t remember a thing until the end, when the Glamour Clinic lady had me seated at one of those basins where you get your hair washed at beauty parlors. I was in the chair, tipped back, head in the big metal tray, as she talked about my eyebrows. She may have plucked one or two stragglers. I just remember she was talking about my eyebrows when a voice was heard in the doorway. I say voice because I was flat on my back and the Glamour Clinic lady had her back to the door.

“I know I’m early, but ….”

“No. No,” said the Glamour Clinic lady. “Come right in.”

It would be hard to imagine a more sincere welcome. The Glamour Clinic lady’s heartfelt Thank you! to a merciful god for her deliverance.

No need to imagine the rest. She snapped me up to a sitting position with a speed that it’s a wonder my eye balls aren’t still spinning.

When I looked to the doorway, I understood the silence that followed. Settled over the otherwise empty expanse of the Glamour Clinic.

A speechless silence.

The next appointment was having trouble getting in.

She had outdone my flying tiger. With the help of some well-shaped cardboard and gray paint, she was a battleship.

Returning to my room, I sat down at my desk, pulled out a piece of stationery, and, pen poised, began.

Dear Mother,

About my appointment at the Glamour Clinic ….

Featured image: College women playing bridge, 1942 (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Good Lord Val, what a tale you tell here, in such vivid detail. I almost feel like I was part of the adventure myself!

The Blue Room, marriage, budget, glamour clinics. I can see how it WOULD make your head spin!

I liked the paragraph about the Flying Tigers. It was during World War ll after all. Thanks for sharing these memorable adventures.