5-Minute Fitness: Pelvic Curl

Strengthen your spine with the following move: “The pelvic curl is an amazing exercise for improving spinal mobility and movement: The goal is to feel the articulation rolling through your spine one vertebra at a time,” says Robin Long, certified Pilates instructor and founder and CEO of The Balanced Life.

Pelvic Curl

- Lie on mat with knees bent and feet flat on floor hip-distance apart

- Inhale. Exhale, tucking pelvis and curling spine one vertebra at a time into bridge position as shown.

- Inhale at top of bridge and stretch until your knees reach over toes.

- Exhale, softening chest and slowly curling spine to the ground.

Gradually work up to 10 repetitions daily.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Courtesy The Balanced Life

In a Word: Beauty and Strength in Calisthenics

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When I was in grade school, back in the 1980s, nothing elicited a groan in our daily physical education classes like the word calisthenics. Historically, calisthenics is a collection of exercises that use the body’s own weight as resistance — think push-ups, sit-ups, and burpees — so little is needed in the way of equipment, maybe a bar for balance or some chin-ups. To my younger self, though, calisthenics were practically a punishment: straightforward exercise for the sake of exercise instead of one of the many more fun and interesting forms of physical exertion we could have been enjoying, like dodge ball, an obstacle course, or even square dancing.

What I didn’t know then (though it would scarcely have altered my opinion) was that many of those calisthenics exercises were ancient, that I was doing the same moves Greek and Roman soldiers had done millennia before to prepare their bodies for battle.

Though the exercises themselves are well aged, that word calisthenics is today not even 200 years old. The first part of the word is from a Latinized version of the Greek kallos, “beauty,” making it etymologically related to the “beautiful writing” we call calligraphy. Add to this the Greek sthenos, meaning “strength,” and you have a description not of what calisthenics is but what it was meant to do.

Though the type of exercises we think of as calisthenics have been around since ancient times, the concept called calisthenics — exercises of “beauty and strength” — was developed during the 1820s. They were targeted specifically toward women, for whom other types of exercise were considered too strenuous. As the name implies, calisthenics were employed not only to help women build strength but to help maintain the beauty standards of the day: a nice figure, proper poise, and graceful movement.

Like any other exercise fad (jazzercise, anyone?), calisthenics found its way into the public eye in all manner of ways. We even published calisthenics exercises in the Post. The following clip comes from our April 14, 1832, issue. Notice how the gender of the “pupil” is assumed:

Of course, in our more enlightened times, calisthenics are for everyone, much to the disdain of gymnasiums full of groaning P.E. students.

Featured image: Bojan Milinkov / Shutterstock

Your Health Checkup: Exposing the Myth of 10,000 Steps per Day

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

Without doubt, exercise is an important activity to help achieve and maintain better health. But how much is necessary? Current guidelines recommend 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise, a little more than 20 minutes per day. Can you do less and still benefit? Probably yes, but the benefits may be less.

We hear a lot about the need to walk 10,000 steps a day and the use of wearable technology to keep track of the number of steps taken. Since the average number of daily steps measured by smartphones is approximately 5,000 worldwide and 4,800 in the United States , one can ask whether we are jeopardizing our health by not walking more.

But what is the source of the 10,000-step recommendation, and how valid is it?

It turns out that the advice likely derives from the trade name of a Japanese pedometer sold in 1965 by the Yamasa Clock and Instrument Company called Manpo-kei, which translates in Japanese to “10,000 steps meter.” No scientific evidence exists to support walking 10,000 steps daily. Further, while walking is a basic activity of locomotion, people of different ages, sex, and fitness status walk at different speeds and on different terrains, one can question whether “one size fits all.” If not, is the recommendation bunk and should we ignore it? Because I walked only 5,000 steps today, am I at risk?

To answer that question researchers set out to determine how many steps per day were associated with lower mortality and whether the intensity of the steps impacted the outcome. In a cohort study of almost 17,000 older women (mean age 72 years), they measured steps/day over seven days using an accelerometer worn on the hip.

During a follow-up of 4.3 years, they found that women who averaged approximately 4,400 steps/day had a 41 percent lower mortality rate compared with the least active women who took approximately 2,700 steps/day. Mortality rates continued to decrease as more steps per day were taken and finally leveled off at approximately 7,500 steps/day. The intensity of the steps taken was not clearly related to a reduced mortality after accounting for the total steps/day.

Since the average walker takes between 2,000 and 2,500 steps per mile, translated into miles, 4,400 steps would be around two miles per day, and 7,500 steps would be at least three miles per day.

Whether you walk, lift weights, swim, or whatever, exercising enables you to take control of your own health and well-being, reduce stress, maintain mental acuity and productivity, and decrease the risk of heart disease and some forms of cancer. To begin, pick an activity you enjoy doing and will likely continue. If you are out of shape, start small, maybe ten minutes a day or a quarter of a mile walk. Exercise with a friend (keep your distance and wear a mask) if you need motivation and keep a written record to remind you what you’ve accomplished.

In addition to being enjoyable, the rewards of exercising are great. Just get out and do it.

Featured image: Shutterstock

5-Minute Fitness: Building Rainbows

Don’t just sit there. “This move not only shapes your glutes, it helps improve hip joint mobility and stability,” says Elise Joan, Beachbody Super Trainer and creator of Barre Blend (beachbodyondemand.com).

Rainbows

- Stand tall, then fold over as comfortable with hands shoulder width apart on a counter or stable chair.

- Extend right leg back and lift to a comfortable height with toe pointed. This is the top of your rainbow!

- Lower leg to cross slightly behind and across standing leg until toes tap the ground.

- Lift leg through starting height and tap toes down on the other side.

- Repeat, extending left leg back.

Gradually work up to 10 repetitions on each leg.

Ready for More?

After Step 4, lift and hold leg at top of your rainbow and make one-inch pulses up, keeping back flat and abs engaged.

Gradually work up to 20 pulses on each side.

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Beachbody

5-Minute Fitness: Be Nice to Your Neck

Dial back neck and posture problems. “Using handheld devices and computers has caused us to develop rounded shoulders and forward heads. And, older folks tend to look down more to watch their steps and lose trunk strength, leading to similar changes,” says Arizona-based physical therapist and ATI Physical Therapy clinic director Eric Shifley.

Neck Soothers

- Hold each stretch 5-10 seconds and repeat daily. 1 Stand or sit with chin tucked to chest and chest elevated. Lower ear toward one shoulder (keep ear lined up with shoulder — no forward head postures). Repeat to other side.

- Stand or sit tall. Gently pull back of head toward one armpit as shown. Repeat to other side.

- Stand or sit with hands clasped together in front of chest. Look downward, reaching forward with hands.

- Stand tall facing corner with hands on walls about shoulder height and outside shoulder width. Lean forward, squeezing shoulder blades together, and slide hands down wall toward waist.

This article is featured in the November/December 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Your Weekly Checkup: Exercising Can Help You Live Longer

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

In January 2018 I wrote about the importance of exercising and suggested that readers start the New Year with a resolution to exercise daily. Recent studies have underscored that recommendation, even suggesting that the risks of not exercising were the same or higher than smoking or having coronary disease or diabetes.

Cleveland Clinic researchers studied 122,000 patients who underwent stress testing and found that increased cardiorespiratory fitness was directly related to reduced long term mortality. There was no limit to the positive effects of aerobic fitness, with extreme fitness associated with the greatest benefit. This was especially true for patients older than seventy years and those with high blood pressure. Extreme fitness provided additional survival benefit over more modest levels of fitness, so that extremely fit people lived the longest.

In fact, elite performers older than seventy years had a nearly 30 percent reduced risk of mortality compared to high performers. For those with hypertension, the elite performers had a reduction in all-cause mortality of almost 30 percent compared to high performers. Elite performers enjoyed an 80 percent reduction in mortality risk compared to the lowest performers.

These results do not support the potential for cardiovascular risk in athletes exercising above a certain training threshold, and there does not appear to be an upper limit of aerobic fitness beyond which a survival benefit is no longer observed.

Older patients may also benefit from a reduction in overall frailty and the ability to maintain physical independence.

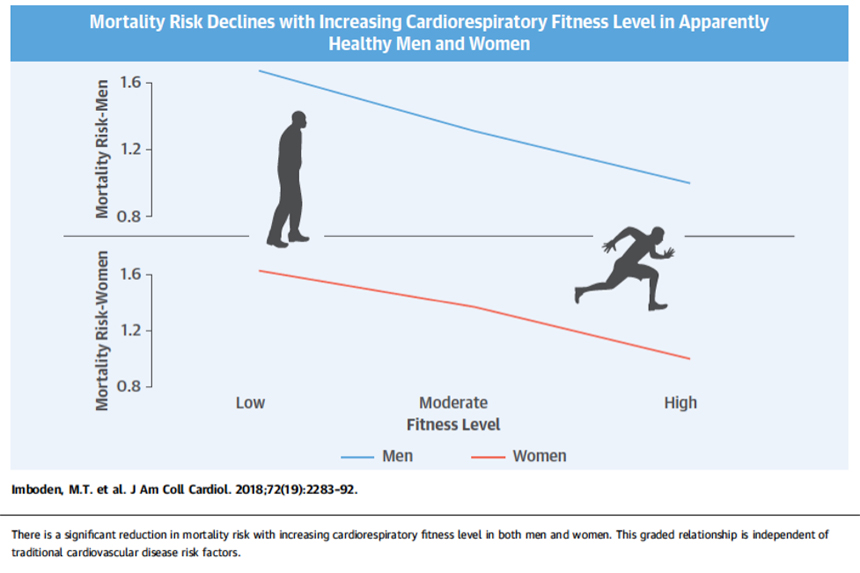

A second study of over 4,000 apparently healthy men and women self-referred for exercise stress testing were followed for 24 years. Each increase in exercise fitness was associated with a reduction in mortality from any cause for both men and women, and specifically from death due to cardiovascular disease and cancer.

The second edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans from HHS recommends that children 3 to 5 years old be active throughout the day, with at least 3 hours of daily active play. Children and adolescents aged 6 years through 17 years should strive for at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity, which can include anything that increases heart rate such as running or walking. Climbing on playground equipment, jumping rope, and playing basketball can also make this group’s bones and muscles strong. Adults should perform at least 150 to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity such as fast dancing or brisk walking. Muscle-strengthening activity like push-ups and weightlifting is also recommended 2 days per week.

The results are in and they are unmistakable. Exercise is good for you. A daily workout will help you live longer and live healthier. So, Couch Potato, get up, stop watching television or fiddling with your computer, and go do it! Run, walk, play sports — it doesn’t matter what you do, but do something!

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Relapse Prevention, Part 3

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Practice Messing Up

Yes, you read correctly, and not everyone agrees with me on this one. Practice messing up — eat junk food? Isn’t that like telling an alcoholic to drink just a little bit?

I wouldn’t give this advice to an alcoholic, but food isn’t the same as alcohol. We have to eat in order to survive. Alcohol is optional and we can choose to totally abstain from it. When it comes to food, we must manage our diet in one way or another. Labeling foods unhealthy and then totally abstaining from all of them can be an overwhelming and unnecessary task. Where should you draw the line? The list can become endless and leads to frustration. You start feeling guilt about eating from the wrong list, like an addict who hijacked his recovery.

Wouldn’t it be nice to enjoy not-so-healthy food without feeling like you messed up each time? Practicing is the only way to do this. I’ve met many folks who view certain foods as bad and when they eat that food they are being bad. They associate ice cream, fudge, or gooey chocolate chip cookies with lack of willpower or being out of control. Over time this view becomes part of a self-fulfilling prophesy. When they eat something loaded with fat and sugar they view themselves as out of control. As a result of these beliefs, they eat the dessert in an out-of-control way. Guilt prevents them from enjoying the food, and sometimes they shame themselves back to eating only from the healthy-food list. At other times, especially when their defenses are down, they veer way off track. It’s sort of a shame.

It’s true that we don’t need Ho Hos, Doritos, or bacon double-cheeseburgers served between two doughnuts, and it may be a good idea to add a few items to the “Food I Refuse to Put in My Mouth” list. Yet some foods give us a great deal of pleasure, even though they have little redeeming value. We can make these foods fit into an overall healthy diet. Here’s what happened during a meeting with a patient named Theresa:

Theresa smiled at me and said, “So let me get this straight. My assignment for this week is to eat chocolate?”

“It is,” I said. “Look, you really enjoy chocolate and you don’t want to entirely cut it out of your diet, right?”

“That would be accurate.”

“So, to me, it makes sense to practice eating it so you have a sense of control and confidence when you do.”

Several times per week, usually on the weekends, Theresa ran errands and would have an intense craving for chocolate. Sometimes she resisted the cravings but at other times she gave in — and gave in big time. With urgency in her step and intention in her eyes, she’d grab a bag of chocolate miniatures at the self-checkout line. She knew she was breaking the rules so she had to do it fast, before logic could prevail. She would then get in her car and rapidly devour half the bag before slowing down. Defeated, she would finish the bag of chocolates while sitting in the parking lot of the grocery store. She discarded all evidence — receipts, wrappers and the candy bag — before driving home, hoping to forget anything out of the ordinary happened. Our conversation went something like this.

“So tell me how much you enjoy these bags of chocolate,” I said.

“At first it tastes very good, I guess, but it’s also like getting rid of a craving.”

“So it’s taking something unpleasant away, the craving, as well as giving you pleasure?”

“Exactly. At times the chocolate isn’t as good as I think it’s going to be. It reminds me of how I used to crave cigarettes even though I didn’t always enjoy smoking. Sometimes I liked it quite a bit, but sometimes I smoked just to get relief from the craving.”

“That makes sense,” I said. “Now I want you to imagine that eating chocolate is okay, for just a minute. Maybe you can think of chocolate as God’s gift just for you! It’s not wrong in any way for you to eat it.”

“That sounds nice,” she said, as she opened her eyes wide and wrapped her thumb and index finger around her chin.

“You don’t have to fight wanting it with I shouldn’t have it,” I said.

“I like that idea,” she said, nodding her head.

“If you felt this way, how much chocolate would you eat before you stopped?”

“Oh, I’ve never thought of chocolate that way. I don’t know exactly, but probably half of the bag or less.”

“Why less than you eat now?”

“I eat the second half of the bag because I’ve already messed up and it’s sitting right beside me in the passenger’s seat.”

“Now I want you to consider the value of the chocolate to you. Let’s use an analogy: When is the last time you bought a car?”

“I bought one two years ago,” she said.

“Was it new or used?”

“It was new, the only new car I’ve ever owned.”

“How did you make that decision?”

She shrugged. “I thought about what I wanted and how much I was willing to pay for it.”

“So cost was a consideration?” “Absolutely.”

“Let’s think about your chocolate this way,” I said. “You want it, but there are costs, such as calories, how you feel after eating, etcetera. How many calories are you be willing to spend to get what you want?”

“The first seven or eight miniatures are really enough for me. I would feel like I got my chocolate fix and it was in my budget. I think they’re about 30 calories each, so I would spend 200 to 250 calories.”

“Would you feel deprived?”

“I’m not sure, but I don’t think so. I’d actually feel like I got what I wanted in two different ways—I got some chocolate and I stayed within a reasonable calorie budget. Sure there’s a little restriction; if I were God I’d make chocolate calorie free!”

“What we just did together—can you do it on your own this week?”

“You mean eat seven or eight pieces of chocolate?”

“Well maybe, but I believe the way you think about chocolate is the first step.”

“Okay, but do you really want me to eat some after I’ve thought about it?”

“I think practice may help you, but I’m not sure if buying a whole bag of chocolate is the best way to approach this. Even if we work on your thoughts, having a whole bag beside you is difficult to resist. Do you think you could deal with the whole bag?”

Laughing, “No; I think it would be too hard for me to stop.”

“Do you like any candy bars as much as you like the miniatures?” I asked.

“Actually I do. I guess in my mind I’m always telling myself I’ll just eat a few pieces per day, so I buy the minis.”

“How about if we plan on buying a candy bar this week?”

“You’re giving me permission?” she asked.

“Yes, but can you give yourself permission?”

“I think so.”

“I also want you to try to eat slowly and enjoy it. Take small bites and savor each one. You might even glance at your watch and see how long it takes you to eat it like this.”

“Should I do this each time I have a craving?”

“What do you think is the best approach?”

“I don’t think that’s a good idea, because what if I have a craving every day or twice per day?”

“Good point. You’ve used a lot of good methods to ride out cravings in the past. I suggest you continue using strategies like distraction, waiting 30 minutes before you decide whether or not to eat, or distracting yourself with a fun activity.” I paused to let my words sink in, then added, “But I still think you need to practice eating chocolate in a healthier way. Let’s get specific about how you can have a guilt-free rendezvous with your candy bar.”

“I think Saturday afternoon is the best time. I would enjoy it most because, although I’m running errands, I’m not in a hurry. “

“Where do you want to eat it?”

“I know people say you should eat at the table, but I just don’t think that will work for me. I like taking a break in my car. I tend to associate eating in the car with a binge, so maybe if I practice eating less while in the car it won’t be such a problem in the future. Can I try it in my car? I’ll just sit in the grocery store parking lot and listen to the radio — I won’t drive and eat.”

“That sounds reasonable for now,” I said. “I do think you may like eating in the car because it’s private and somewhat secretive, but we can talk about that later. Let’s give it a shot for this week.”

Theresa continues to work on controlling her chocolate intake. Many times her goal is to abstain from chocolate altogether. But our practice with moderation has increased her confidence in eating smaller amounts of one of her favorite foods. When she eats chocolate according to her plan, she experiences guiltless pleasure and satisfaction. She also maintains her 30-pound weight loss.

The best practice is one you think through ahead of time. We all have many activities, like vacations, holidays, weekends at the lake, or running errands that make managing weight more difficult. If we want to become better at loosening but not letting go of the reins, we need a plan before we practice. When we make a plan and follow it, we feel like we’re on track — which is crucial when the plan involves deviating somewhat from our usual healthy eating and physical activity regimen. I caution you against a common error related to practicing eating the foods we crave: rationalization. It’s tempting to start viewing all our dietary indiscretions as practice, when in fact they aren’t. Healthy practice requires forethought rather than an explanation after the fact. Your plans should be somewhat systematic with specific and measurable goals. After the practice, evaluate your experience and plan for the next session.

Looking for Lessons

I was wrong, I made a mistake, my plan didn’t work and your idea was better. Those are hard phrases for me to say — and words my wife loves to hear.

–Henry Ford

Life is filled with learning experiences, and the more we try to do, the more we learn. Stretching ourselves brings the risk for failure — but we often learn more from failure than from success. As Henry Ford said, “Failure is the opportunity to begin again more intelligently.” When we use failure to make adjustments, we’re still making progress. And so it is with weight management. When you give in to food temptation or stop exercising after an exhausting week, it’s tempting to forget the whole thing and start over. But if you start over without evaluating what went wrong, you’re likely to make the same mistakes again.

After a few weeks off for the Christmas holidays, many of my clients come into the office and say, “I need to get back on track.” They lay out plans to get to the gym on a regular basis, eat “clean,” and start recording their food again.

I agree with getting back on track, but I also ask them to review what happened so they can be more prepared next season. In fact, I often ask patients to write about their holiday experience: What went well, what didn’t work, and how they could handle it better. These holidays come every year, so the temptation is predictable. For many people the “holiday eating season” begins before Halloween with trick-or-treat candy and lasts until January. That’s two months, or one-sixth of the entire year. It makes sense to learn from the previous year and develop a plan that will lead to a guilt-free and enjoyable season.

Your Weekly Checkup: My New Year’s Resolution — Exercise!

We are pleased to bring you “Your Weekly Checkup,” a regular online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

“Whenever I get the urge to exercise, I lie down until the feeling passes.” This quote, repeated often, is attributed to Paul Terry, founder of the Terrytoons animation studio. The precise source is less important than the thrust of the message: although said in jest, its impact is harmful to your health!

Despite the fact that study after study has validated the benefits of exercise, many Americans still sit all day at work, watch TV at night, and drive short distances instead of biking or walking. They do not realize that even mild exercise such as walking slowly or performing household chores like vacuuming, washing windows, or folding laundry can be beneficial. Two recent studies, one from Harvard investigators and the other from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, examined the exercise patterns of a large number of people, and found that the most active folks reduced their mortality by 50 to 70 percent compared with the least active, sedentary participants.

One of the most exciting recent discoveries about the benefits of exercise comes from the Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom. They found that a single exercise session can offer immediate protection to the heart through a mechanism called “ischemic preconditioning.” Exposing the heart repeatedly to short episodes of inadequate blood supply (ischemia), such as might occur during strenuous exercise, protects the heart to resist a longer, more serious episode of ischemia. The investigators found that a single vigorous workout provided cardioprotection lasting 2-3 hours, while repeated exercise sessions weekly yielded even greater and longer protection. The benefits of exercise can help mitigate the negative impact of other risk factors such as diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure.

What should you do for 2018?

- Pick an activity you enjoy and are likely to continue: dancing, bowling, golf, walking the dog, or playing with your children or grandchildren.

- Start small: maybe 10 minutes initially, and gradually increase the duration and intensity over time.

- Exercise with friends: If you need motivation, plan to exercise with friends at a fixed time, four or five days a week. Knowing your colleagues are waiting is more likely to keep you in the game.

- Write it down: maintain a diary that details what you do, and your response to it. Finding that you can exercise longer with greater ease is a superb incentive to continue to even greater heights.

Exercising enables you to take control of your own health and well-being, reduce stress, maintain mental acuity and productivity, and decrease the risk of heart disease and some forms of cancer. Make it your number one New Year’s resolution!