Tiger Woods and More Triumphant Sports Returns

As Tiger Woods steps onto the grass at The Masters this week, the eyes of the sports world are upon him. Woods, returning from what many had thought was a career-ending accident, has defied the odds before. In 2019, Woods won The Masters after an 11-year drought at major tournaments. Could Woods make another thrilling return? In that spirit, here are five other returns by athletes that should never have been counted out.

Before we look at the Big Five, here’s a Bonus Two-for-One Special:

Bonus: Magic Johnson and Larry Bird

The Best of the Dream Team (Uploaded to YouTube by Olympics)

In 1992, Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics was on the verge of retirement. Plagued by back problems, he’d had a disc removed, missed 37 games during that season, and was headed out the door. His great friend and nemesis, Magic Johnson of the L.A. Lakers, had retired in 1991 after being diagnosed as HIV-positive. However, the two had a chance for one last run together: the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. Joining one of the greatest athletic teams ever assembled, Bird, Magic, and the rest of Team USA stormed their way to a gold medal. For basketball fans that had watched the pair battle from the 1979 NCAA Finals and through the entire 1980s in the NBA, well, that’s why they called it “The Dream Team.” While Bird did retire after the Olympics, Magic returned to the NBA as a player in 1996, helping the team get fourth seed in the playoffs. After the Lakers lost to the Rockets, Magic retired for good.

5. George Foreman

George Foreman in 1973 (Photo by Bert Verhoeff via Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

One of the best to ever lace up a pair of boxing gloves, George Foreman took gold in the 1968 Olympics as a heavyweight. Foreman went on to knock out an undefeated Joe Frazier to become heavyweight champ in 1973. His title reign came to an end at the hands of Muhammad Ali at 1974’s legendary “Rumble in the Jungle.” Foreman retired in 1977. After spending several years as a minister, Foreman came back to boxing in 1987. In 1994, the 45-year-old Foreman knocked out Michael Moorer to become the unified heavyweight champion. He remains the oldest man to be heavyweight champion.

4. Bethany Hamilton

This Iz My Story (Uploaded to YouTube by Bethany Hamilton)

Bethany Hamilton excelled at surfing from an early age. An avid competitor by age eight with sponsorships by age ten, Hamilton had her eyes on big titles. However, in 2003 when she was 13, the unthinkable happened. During a surfing excursion, a 14-foot long tiger shark bit off Hamilton’s left arm below her shoulder. It was a trauma that would have crushed most people, but not Hamilton. She returned to the waves a mere month after the incident. In 2005, she took first in the NSSA Nationals and won her first pro tournament in 2007.

3. Mario Lemieux

Lemieux Scored 100 Points 10 Different Times (Uploaded to YouTube by NHL)

There’s no debate about the greatness of Mario Lemieux. He’s widely regarded as one of the greatest hockey players ever. Lemieux debuted for the Pittsburgh Penguins in 1984 and quickly became a star. He was Rookie of the Year and was only outscored in his sophomore season by Wayne Gretzky. Though Lemieux would struggle with back injuries, he was a major force in the NHL as one of the sport’s biggest scorers. In 1993, “Super Mario” was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma. Undeterred, he continued to play, even on the same day as radiation treatments. Incredibly, he won the scoring title that year. Though he continued to play at a high level, the years of back problems and his earlier battle with cancer factored in to Lemieux’s decision to retire in 1997. With the Penguins facing money trouble, Lemieux came in with a plan to become the team’s majority owner. He helped turn things around the ledger, and then did something more incredible: he returned to the ice. Lemieux played from 2000 to 2006, ending his career with dozens of records and an Olympic gold medal from 2002.

2. Michael Jordan

The Best of Jordan’s Playoff Games (Uploaded to YouTube by NBA)

For Michael Jordan, an NBA championship wasn’t a question of “if,” but a question of “when.” Joining the league in decade dominated by the Celtics and the Lakers, Jordan turned around the fortunes of the Chicago Bulls. He led the team to a finals win in 1991, and then again in 1992 and 1993. Tragically, Jordan’s father, James Jordan, Sr., was murdered by carjackers in July of 1993. That October, Jordan retired, citing his father’s death, a loss of desire to play, and general exhaustion. After detour to play minor league baseball, Jordan issued a two-word press release (“I’m back”) and returned to the NBA in March 1995. He lifted the struggling Bulls into the playoffs, where they lost to the Orlando Magic. As the meme goes, Jordan took that personally. Over the next three seasons, Jordan led the Bulls to championships in 1996, 1997, and 1998, cementing his status as one of, if not the, greatest to ever play the game.

1. Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali – The Greatest of All Time (Uploaded to YouTube by Nonstop Sports)

How could The Greatest now be #1? Muhammad Ali’s life was defined by battle. Whether it was taking the Olympic gold medal in Rome in 1960 or taking his draft evasion conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, Ali never backed down from a challenge. After becoming champion in 1964, Ali voiced his opposition to the war in Vietnam and proclaimed his status as a conscientious objector. His titles were stripped, and Ali fought the decisions in court. The conviction was overturned in 1971 and Ali found himself in the position to challenge Joe Frazier for the heavyweight title. Both men were undefeated going in, but it was Ali that left with his first professional loss. Of course, that didn’t mean that Ali was done. He faced Frazier again in 1974, defeating his old rival to get a shot at the then-current champ, George Foreman. At the “Rumble in the Jungle,” Ali knocked out Foreman to retake the title. He would eventually retire in 1981, a three-time heavyweight champion

Caddyshack Turns 40: Nine Things You Didn’t Know About the Cinderella Story

EPSN thinks it might be the funniest movie ever made about sports. Some point to it as another example of how Saturday Night Live incubates talents that are suitable for the big screen. And others consider it the best of the “slobs vs. snobs” subgenre of comedy. However you score it, Caddyshack has been one of most popular and most loved film comedies (almost) since its release 40 years ago this week. In honor of its longevity and continued hilarity, we’ll shoot a (front) nine full of things you didn’t know about Caddyshack.

1. It Was Created by Caddies

Caddyshack star Bill Murray is regular on the Celebrity Pro-Am circuit (Uploaded to YouTube by PGA Tour)

Writer and co-star Brian Doyle-Murray had the idea for the film based on his own experiences working as a caddie. His brothers John and Bill Murray had as well, as had their friend Harold Ramis. Brian, Bill, and Ramis had all been members of the Second City comedy troupe; Ramis also worked with Bill Murray on The National Lampoon Radio Hour and was one of four writers credited on Murray’s film, Meatballs. Douglas Kenney, who had founded National Lampoon magazine and co-wrote National Lampoon’s Animal House with Ramis and Chris Miller, came aboard and collaborated with Ramis and Doyle-Murray on the screenplay for Caddyshack. In 2002, the Murrays and their fourth brother, Joel, created and appeared in the Comedy Channel series The Sweet Spot, which featured the brothers playing golf at top-notch courses.

2. What Ramis Really Wanted to Do Was Direct

With his background writing for SCTV, National Lampoon, and two successful screenplays under his belt, Ramis was able to assume the director’s chair. Doyle-Murray took the role of caddie supervisor Lou Loomis, while Kenney would take a background role as one of Al Czervik’s (Rodney Dangerfield) hangers-on. The small scale of Kenney’s role was similar to his turn as Stork in Animal House, which he assigned himself and where he had only two lines; he’s the one who ultimately leads the marching band into a dead end. Brian and Bill’s brother John pulled double-duty on the film, appearing as a caddie extra and working behind the scenes as a production assistant.

3. Chevy Chase Was a Logical Fit

The “Be the Ball” Scene (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

Although Chase had passed on the role of Otter in Animal House (which was played by Tim Matheson), he agreed to join Caddyshack. Kenney was one of his closest friends, and he’d worked with Ramis and Bill Murray on The National Lampoon Radio Hour. An original member of the Saturday Night Live cast, Chase had also been the first to leave and find film success. By the time that he shot Caddyshack, he’d already had a hit with Foul Play. For his part, Murray was still on the show and would work shooting his scenes in the film around his SNL schedule. Doyle-Murray was also still working for SNL as a writer and would later be a full cast member.

4. There Are Too Many Palm Trees in Florida

Production began in the fall of 1979. Rolling Hills Country Club in Davie, Florida served as the location for the shoot; today it’s called Grande Oaks Golf Club. Ramis chose that location because it was one of the few Florida courses that didn’t have palm trees. The director was particular about that because he wanted the movie to feel like it could be in the Midwest. One downside of shooting in Florida was that the production had to contend with delays caused by Hurricane David, which briefly touched Florida on September 3.

5. The Film Made Rodney Dangerfield a Movie Star

Rodney Dangerfield was already established as a stand-up comedy star before Caddyshack. Dangerfield broke out after an appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1967. He would regularly return to that show and became a popular guest on programs like The Dean Martin Show and The Tonight Show (where he was a guest 35 times). In 1969, he and Anthony Bevacqua created Dangerfield’s, a comedy club in New York, which became one of the home bases of HBO’s Young Comedian Specials. Dangerfield’s stand-up background and Chase and Murray’s grounding in sketch comedy made them all quick on the draw with improv, an environment that led to their roles getting expanded and improvised bits (like Murray’s flower-destroying fantasy monologue about playing at Augusta) making the final film. For his part, Dangerfield was launched into leading his own film comedies like Easy Money.

6. We Should Probably Get These Two Together

The “Mind If I Play Through?” Scene (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The movie was already shooting when Ramis realized that two of the biggest draws in the film, Chase and Murray, had exactly zero scenes together. That may not have entirely been by accident, as Chase and Murray had famously had a contentious run-in backstage at SNL when Chase had returned to host the show. Nevertheless, Ramis, Chase, and Murray went to lunch together and worked out the scene where Ty Webb (Chase) plays a late-night round through groundskeeper Carl’s (Murray) place.

7. The Gopher Has Some Star Wars in Him

John Dykstra won an Academy Award for special effects work that he did for Star Wars, but he had already been famously pushed out of Industrial Light and Magic by George Lucas for budget and scheduling issues before that film was finished. Dykstra would go on to create special effects for a number of other high-profile projects, including the original pilot and theatrical film for Battlestar Galactica. Dykstra’s team created the gopher and his lair while also handling lightning and other visual effects in the film.

8. The Kenny Loggins Film Reign Begins Here

Kenny Loggins performing “I’m Alright” (Uploaded to YouTube by Kenny Loggins)

Kenny Loggins was already a music mainstay before Caddyshack. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band did four of his songs in the 1970s, which is also when he formed his hit duo with Jim Messina. Loggins and Messina did seven albums in five years. He co-wrote the Doobie Brothers hit “What A Fool Believes” and wrote “I Believe in Love,” which Barbra Streisand sang in 1976’s A Star is Born. He contributed “I’m Alright” to the Caddyshack soundtrack, and it was used as the main theme of the film (and for the gopher’s memorable dance outro). He earned the nickname “The King of the Soundtrack” for his film work throughout the 1980s, which included hit songs for Footloose, Top Gun, Over the Top, and the less-said-the-better Caddyshack II: Back to the Shack.

9. The Hard Road to Classic Status

Harold Ramis on Caddyshack 30 Years Later (Uploaded to YouTube by American Film Institute)

The film was financially successful, but critics weren’t too kind. However, fans embraced it and it went on to an even bigger second life on cable and video. Critics reevaluated the movie over time as they realized how deeply funny and quotable it was. Bill Murray and Harold Ramis (on camera this time) reteamed the next year in Stripes, which was an even bigger success; Murray and Ramis did three more films together: Ghostbusters, Ghostbusters II, and Groundhog Day. Chase had major successes for the rest of the decade, including Fletch and three films in the National Lampoon’s Vacation franchise. Today, Caddyshack is regarded as a comedy classic and regularly places on lists of the American Film Institute, such as 100 Laughs and 100 Movie Quotes. The Murray brothers also own the Murray Bros. Caddyshack restaurants, two of which are still open in St. Augustine, Florida and Rosemont, Illinois.

Featured Image: Bill Murray attends Isle of Dogs New York special screening at Metropolitan museum on March 20. 2018. (lev radin / Shutterstock.com)

You Be the Judge: Reader Favorite: Looking for a Fair Way

In 1977, Nebraska businessman and avid golfer Dennis Circo developed an exclusive residential neighborhood dubbed Skyline Woods. Its centerpiece was an 18-hole golf course. As the developer, Circo sold lots, built homes, and transformed the golf course into a country club, adding a clubhouse, pool, and tennis courts. With all of its amenities, buyers paid a premium for home lots.

By 1990, Skyline Woods was well established, with 90 homes built around the country club, and Circo thought the time was right to sell the club to a golf course management company. Unfortunately, the golf pros ran into financial hazards. They ran out of “green,” and the only course of action was for Skyline Woods Country Club to file for bankruptcy in 2004. To pay off debt, the bankruptcy trustee auctioned off the property in 2005. A group of Skyline Woods homeowners tried to buy the club, but were outbid by Liberty Building Corporation, a development company owned by David Broekemeier.

Here’s where things got sticky. The federal bankruptcy court transferred property to Liberty, free and clear of all obligations. Shortly after, Broekemeier met with homeowners and club members to inform them he had no obligation to honor memberships, offering the option to play the course if they paid fees like anyone else.

If that was bad, what happened next was worse. In spring 2006, Broekemeier closed the club, posted “no trespassing” signs, and began cutting down trees to clear land where he planned to build a condominium complex and water park. Teed-off homeowners sued Broekemeier in Nebraska State Court, requesting a restraining order to prevent further damage to the land. They claimed implied covenants as homeowners in the golf community guaranteed the only use of land was as a golf course.

They reasoned Broekemeier might own the golf course free and clear but was free only to use it as a golf course. Homeowners added that no matter how you slice it, Broekemeier was well aware of their covenants, as he had also built a golf community adjacent to Skyline Woods. And, like Circo, he marketed the course’s proximity and views to sell lots. And there were rumors that he was going to redirect the golf course toward his neighborhood, leaving Skyline Woods homeowners with views of condos and a water park.

In response, Broekemeier came out swinging with a motion to dismiss the case. His first argument was that the state court had no jurisdiction to interfere with the federal bankruptcy order. Second, even if the state court did have skin in the game, the covenants were unenforceable because they were never recorded. Finally, he said Nebraska law protects bona fide purchasers from restrictive covenants when there is no notice.

How Would You Rule?

District Court Decision — 2008:

Round one was won by the homeowners. A Nebraska court found that they did indeed have implied restrictive covenants; Broekemeier was aware of the covenants; and finally, the bankruptcy sale of the property did not discharge the covenants because they belonged to the homeowners, not the golf course. The court ordered Broekemeier to either reopen the golf course or maintain it in a fashion that would not devalue the property of homeowners. Broekemeier chose the latter.

Round two: After six years of legal turf wars, the golf course never reopened, eventually becoming an eyesore due to lack of maintenance.

Aftermath — 2012: Game over. The land was sold. At that time, the new owner planned to spend $7 million to build a premier golf course.

This reader favorite originally appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of The Saturday Evening Post and was republished in the May/June 2020 issue. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Cartoons: Levity on the Links

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Hickey

November 4, 1950

September 8, 1951

Mort Walker

September 8, 1951

August 19, 1950

July 15, 1950

Frank Ridgeway

June 30, 1951

Bob Barnes

December 2, 1950

Cartoons: Golf Grief

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

September 25, 1948

September 4, 1948

Robert Day

August 28, 1948

Tom Henderson

June 5, 1948

Douglas Borgstedt

April 22, 1950

Al Johns

January 5, 1952

Jeff Keate

March 18, 1950

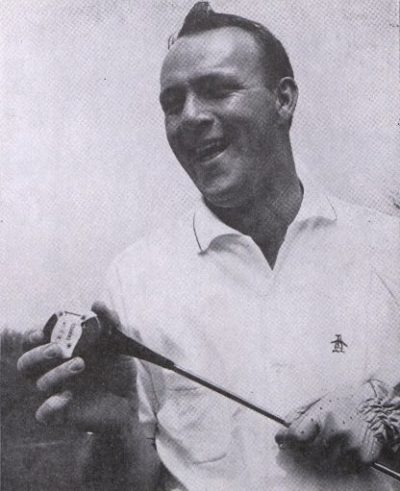

Arnold Palmer Introduces the Grand Slam

In 1960, Arnold Palmer became the first professional golfer to win mote than $75,000 in a single season. More than halfway to this goal in June, the 30-year-old talked with the Post about how he planned to make his mark on the sport.

I Want That Grand Slam

By Arnold Palmer as told to Will Grimsley

Originally published June 18, 1960

Ever since I was able to walk I have been swinging a golf club, and ever since I was big enough to dream I have wanted to be the best golfer who ever lived. At one time I was certain that someday I would duplicate Bob Jones’ “grand slam” of 1930 — that is, sweep the United States Amateur and Open Championships and the British Amateur and Opening a single year. Then I found out — to my disillusionment — that to devote the necessary time to golf, yet still remain an amateur, I would need either tremendous wealth or a high-paying job with no responsibility.

For me, such prospects were as far away as the moon. I concluded that if I were going to reach the top in golf, I would have to do it as a professional. It was then that I started thinking about a professional “grand slam.”

When I got off to such a fast start this year — winning five of my first thirteen tournaments, including my second Masters in three years — I determined to make my bid. Now my sights are fixed on winning the four biggest tournaments open to a pro — the Masters, the U. S. Open, the British Open, and PGA (Professional Golfers Association of America). Ben Hogan won the first three of these in his great year of 1953, but had to pass up the PGA. No golfer ever has taken all four in the same year. The odds against it must be at least 1,000 to 1. Yet I feel confident that, with a little luck, it can be done. I want to be the man to do it.

Many people felt that Hogan’s 1953 achievement was at least equal, and maybe even superior, to Jones’ 1930 sweep because of the keener competition Hogan met. I agree. I believe Bob Jones, a wonderful sportsman, also might agree. In his heyday Jones had to beat only a small handful of top-flight players. In a big tournament today, anywhere from 30 to 40 men are capable of winning. Jones always has acknowledged that in his time it was possible to win a tournament with three good rounds and one bad round, whereas now it generally takes four good rounds to come out ahead. I think one major victory today is worth two in the Jones era.

The next major test for me is the National Open at the Cherry Hills Country Club this week in Denver. From there I go directly to Dublin, Ireland, to team with Sam Snead in the Canada Cup matches at Portmarnock Golf Club next week. These matches should help me get adjusted to the new playing conditions I’ll face in the hundredth anniversary British Open at St. Andrews in Scotland beginning July 4. After that comes the PGA championship, which opens at Akron, Ohio, on July 21.

Frankly, I am very excited about the British Open, whether or not I still have any chance for my grand slam by the time I get there. The United States has had only two British Open winners in the last 26 years — Sam Snead in 1946 and Ben Hogan in 1953. Our top golfers seldom compete in this championship; they don’t like to leave the rich American tour for an event which offers a first prize of only about $3,500. I’ll miss tournaments worth about $100,000, but I don’t care. I got into this business primarily to win championships. Money is important to me, certainly, but mainly as a means to an end. The money helps make it possible for me to go after the big titles, and I won’t be happy until I win them all.

If I miss out on a slam this year, I intend to keep trying. I am 30 years old — five years younger than Hogan was when he won the first of his four National Opens — and fortunately I am healthy and strong. I believe I have at least 10 more good years of tournament golf ahead of me. Pap — my father, Milfred Palmer, who taught me almost everything I know about golf — insists I’ll be playing competitively until I’m 50.

“The main thing is to take care of yourself, boy,” he keeps telling me. “A man’s body is like a tractor. Keep it in shape, and it will be serviceable for years.”

I seem to play my best in the big tournaments. For one thing, my game is better adapted to the tougher courses. For another, I can get myself more keyed up when an important title is at stake. I like competition — the more rugged the better. When I get on a hard, exacting course, I feel as if I’m wrestling a bear.

Such a course is the Augusta National, where the Masters is played every year. It’s a course that will snap back at you — even swallow you — when you least expect it. I won there in 1958, then kicked away the 1959 tournament on the final round by taking a six on the par-three 12th hole and missing putts on the 7th and 18th. Art Wall Jr., who birdied five of the last six holes, beat me out by two strokes.

Because of that 1959 disappointment, I went to the Masters this year more determined than for any other tournament I can remember. I passed up the Azalea Open at Wilmington, North Carolina, in order to arrive at Augusta a week in advance. I think I startled Mrs. Helen Harris at the registration desk when I checked in.

“Well, this is my 13th tournament of the year,” I told her. “Why don’t you enroll me as number 13?”

Mrs. Harris did — a bit reluctantly. So, my caddie, Nathaniel Avery, better known as Iron Man, had to wear a big 13 on his back all week. He didn’t like it, but he stuck it out; he has been my caddie there for six years.

I found myself installed as the six-to-one betting favorite for the tournament. Masters tradition has it that the advance favorite seldom wins. Newspapermen kept asking me how it felt to be put on the spot as the man to beat.

“It doesn’t bother me,” I told them. “What the bookies and sports writers say doesn’t affect the way the ball bounces. I never think of such things.”

It looked for a while as if my defiance of superstition might backfire. On the Sunday before the tournament I caught a flu bug and was miserable. I didn’t practice at all on Monday. I got a shot in my hip and stayed in bed the entire day. On Tuesday I played 14 holes. On Wednesday, the day before the opening round, I played only four.

However, when I went to the first tee on Thursday, I felt fresh and eager. I shot a five-under-par 67, with an 18-foot putt on the final hole, and led by two strokes. I putted poorly the next day for a 73, but stayed ahead by a stroke. In the third round, I shot a 72. That sent me into the last round with a one-stroke edge over five tough professionals — Ben Hogan, Ken Venturi, Dow Finsterwald, Bill Casper, and Julius Boros. I now had a chance to equal the 1941 feat of Craig Wood — the only man in the previous 23 Masters tournaments to lead every round.

The final round quickly developed into a three-way battle among Venturi, Finsterwald, and myself. Venturi andFinsterwald, playing four holes ahead, both had two strokes on me at one stage. I was on the 14th hole when Venturi finished with a fine 70 for a score of 283. Finsterwald missed a tricky eight-foot putt and wound up at 284.

In our business they say it’s best to be in the clubhouse with a good score — as Venturi was — and make the guys on the course come and get you. I needed to play those last four holes in one under par to tie, and two under par to win.

The best I could do at the long 15th hole and the short 16th was to stay even with par. As I moved on to No. 17, Winnie, my wife, came out and put her arm around my shoulders. “You’re doing fine, honey,” she said consolingly. Pap, who had come down Saturday from our home in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, gave me a wink and a sign as if to say, “Go get ’em, son.” Iron Man, my caddie, was almost in a state of shock. He fumbled nervously with the clubs, and every time he tried to say something, the words clogged up in his throat.

As for me, I wasn’t nervous. I was keyed up, of course, but the juices in my system were flowing normally. I read later that Venturi said he played the final round without once looking at the scoreboard or checking on what I was doing. With me it was just the opposite. I got reports at every hole. I knew exactly what I had to do. I was confident I could get at least one birdie on the final two holes to tie him — somehow, I always feel I can get a birdie when I need it.

The 17th is a par-four hole of 400 yards. I hit a good drive, but my eight-iron approach sat down too quickly and left me well below the cup — about 30 feet away from it, I would say. I remembered that the year before, on this same hole in the final round, I had missed an easy three-foot putt because I failed to read a slight break to the left. This putt, although much longer, was on virtually the same line. So I struck it boldly, intending that if the ball stayed up, it should break a little left at the hole. It did. It plopped into the cup for a birdie, and half my job was done.

There was high tension and wild excitement all around me at the 18th tee. The only sensation I felt was that my mouth was awfully dry. I would have given 10 bucks for a sip of water. But my main interest was in getting my drive on the fairway so I could be reasonably sure of my par. Par on the 18th is four. The hole is 420 yards and uphill, and we were playing into the wind.

My drive was a good one, a bit to the right. Then I punched a six-iron to the green about six feet to the left of the pin. Again I remembered the last day in 1959. I had had a ball in almost this exact spot. I had become disconcerted by the whirring of newsreel cameras and missed. This time I intended to take no chances. I studied the putt very carefully. I asked the newsreel men to stop their cameras. I gave the ball a solid whack. It dropped. That was the tournament.

“How did you do it?” one friend asked me later. “I would have swallowed my Adam’s apple.” Another said, “With that putt on the 18th, I don’t think I could have brought my putter’s blade back.”

Well, I don’t think I have any stronger nerves than the next man. I suspect it’s just the patience I got from my mother and the ornery bullheadedness I inherited from Pap. My mother and father are of stolid German-Irish stock. Both their families settled in the hilly section east of Pittsburgh in the early 1800s and have been there ever since. Originally they were farmers and landowners. Later some of them, such as my dad, drifted into the steel mills and other lines of work.

Pap never had it easy. When he was just a tyke, shortly after he had learned to walk, he came down with polio and was in bed for months. Then he had to be taught to walk again. Today his left leg is about one-fourth as big around as his right, and he walks with a distinct limp. But he developed into a par golfer. He can chin himself with either arm, and 30 times with both. He swims like a fish.

Pap has served at the Latrobe Country Club in various capacities for 39 years. He first worked there as an ordinary laborer when this nine-hole course was carved out of a mountainside. He helped put the roof on the clubhouse. Later he became greenskeeper and took some courses at Penn State to learn more about grass. Then in 1933, in the midst of the depression, he was made combination greenskeeper and pro at the club at a very modest salary. To keep his growing family in groceries, he had to work in the steel mills during the winter.

Latrobe is an industrial community of about 15,000. It is about 30 miles east of Pittsburgh, off U.S. Highway 30. Three independent steel mills provide most of the employment. There also are some thriving construction businesses. The golf course is now in the process of expanding from nine holes to eighteen.

My family has always lived within a brassie shot of the course. I am the oldest child, born September 10, 1929. I have a married sister, Mrs. Ronald Tilley, 28, living in Washington, D.C.; a brother, Milfred Jr., better known as “Jerry,” 15, and a kid sister, Sandy, 12. None of them is very interested in golf.

I couldn’t have been more than three when I got my first golf club. It was an old iron with a sawed-off shaft. The first thing Pap showed me was the proper grip — the Vardon overlapping grip. I vividly remember swinging the club hours at a time as Pap and his men worked nearby. I’d be swinging at some remote spot on the course, and my dad would walk by and tell me what I was doing wrong. I would correct myself and start swinging some more.

Pap says that’s the reason I have such big hands. “They’re the hands of a blacksmith or a timber cutter,” he says. “You can only get hands like that by swinging an ax or a golf club.”

My father always impressed on me the importance of keeping a firm hold on the club and not letting my swing get too loose. Even as a kid I kept my swing compact. I tried to hit the ball so hard I often would lose my balance.

“Deke is ruining that boy,” some of the club members would say. “He should make the kid swing easy.” Pap, who doesn’t know where he got his nickname of “Deacon,” or “Deke,” never let this criticism bother him. “It’ll work out all right as you get older,” he told me. He was correct.

Although my dad was the club pro, I didn’t have free run of the course. On the contrary, the club maintained the old British aloofness toward professionals and other employees. I wasn’t permitted on the course except on Mondays, when it was closed to members.

I recall I used to draw mother’s wash water on Monday mornings and then rush off to the course to play golf with the caddies. I also played some with my mother, who was quite good for a woman and a real stickler for keeping a correct scorecard. Other times I had to sneak in my practice when nobody was looking. At eight years, I could shoot 55 for nine holes. Then I got down to 50. One day when I was nine, I shot even fives for a 45. I couldn’t wait to run home and tell mother.

“Did you count them all?” she asked skeptically. She and Pap never let me get the big head.

As I grew older I took on more responsibility around the course. I worked the tractors and mowers. I helped in the golf shop. But always I was anxious to get out and hit practice balls. Sometimes I would go out to cut a fairway and, with the job half done, I would park the tractor and start hitting balls. Pap would find me and chew me out.

I guess I was even worse around the shop. “Arnie is the worst caddie master I ever had,” Pap always said.

One day when I was left in charge of the caddie shop, things got a little dull, and I sneaked down to the 8th hole to try out a new club. One of the club officers, an executive at one of the steel mills, picked this time to go by the shop for his clubs. He was hopping mad when he found the door locked.

Although he saw me hitting balls, he didn’t come down and say anything to me about it. Instead he hunted up Pap. He told Pap he would like to get his clubs.

“The caddie master will get them for you,” Pap said.

“Your caddie master is out there hitting balls,” the steel executive told my father coldly.

Pap tried to apologize, but it was little use. The other man said, “Let me have that boy in the steel mill for a while, and I will take some of that starch out of him.”

“I’d rather send him up on the ridges to chop trees,” Pap replied. Although my dad gave me a good dressing down when we were alone, he didn’t like the idea of anyone else pushing me around. I was a headstrong kid, but Pap kept a good bridle on me. He would hammer away at the things I was doing wrong in golf. I would get furious. We would wind up wrangling like a pair of alley cats.

Sometimes I would tell him he was old-fashioned and didn’t know what he was talking about. Pap would get peeved and give me the “freeze treatment.” I would ask him to help me correct some flaw, and he would pout, “I’m an old fogy — I don’t know anything. Besides I’m busy.” Then I would apologize. Pap would give in and work with me. I’ve found out one thing — he’s almost always right.

I played No. 1 on the golf team at Latrobe High School for four years. I lost only one match, to a Greensburg senior when I was a freshman. I won the Western Pennsylvania Junior three times and the Western Pennsylvania Amateur five times.

At the Hearst national junior tournament in Los Angeles around the time I finished high school, Bud Worsham, brother of former National Open champion Lew Worsham, suggested that he could help me get a golf scholarship at Wake Forest College in North Carolina. I leaped at the idea. Pap, with a houseful of hungry mouths to feed, had a tough enough time trying to keep me in golfballs, much less financing a college education for me.

With golf mainly on my mind, but majoring in business administration, I entered Wake Forest in September 1947 and became Bud Worsham’s roommate. Soon I found myself playing against fellows I later was to face on the pro tour. Art Wall and Mike Souchak were at Duke. Harvie Ward was at North Carolina. I won the conference title two times and the Southern Intercollegiate once. I was twice medalist in the National Intercollegiate, although I didn’t win it.

After I had been in college about three and a half years, I lost my roommate when Bud Worsham was killed in an automobile accident. I became restless and quit school to join the Coast Guard. I served three years — a few months in New Jersey and Connecticut, the rest in Cleveland. I had an opportunity to play a lot of golf.

In January 1954, I re-entered Wake Forest, but stayed only a semester. I was still short some credits, and I never got my degree. All this time I was the captive of my strong obsession with golf and my conviction that I could become a better amateur player than Bob Jones was.

I returned to Cleveland and got a job with W. C. Wehnes and Company, manufacturers’ agents. On this job I could work in the morning and play golf in the afternoon. But there was no way I could get off for extensive periods to play in tournaments.

Then came what looked like my big break. A friend of Bill Wehnes offered me a job marketing a revolutionary trailer with a hydraulic lift. He guaranteed me $50,000 a year for two years and promised that I would make enough money thereafter in renewals to enable me to devote myself almost completely to golf. I was in the man’s office to sign a contract when word came that he had been killed in an automobile accident in Florida.

At this time I still wanted to play as an amateur, although I felt a growing urge to get into big-time golf. My restlessness continued when I won the 1954 U.S. Amateur title at the Country Club of Detroit in August, beating Robert Sweeny one-up in the final match.

Three weeks later I was playing in Fred Waring’s tournament at Shawnee on Delaware, Pennsylvania. On the first day of the tournament — a Tuesday — I noticed a pretty, dark-haired girl in my gallery. After I finished I learned she was Winnie Walzer of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a friend of Fred Waring’s daughter Dixie. We were introduced. By Friday night I had proposed. We became engaged and talked about taking a honeymoon the next spring when I went to England with the United States Walker Cup team.

However, now that I wanted to get married, it began to seem impractical to me to remain an amateur all that while. I turned professional on November 19, 1954, signing a contract with Wilson Sporting Goods Company. I talked it over with Pap first, and he didn’t mind. He had wanted to play on the tour himself, but never felt he was good enough or had enough money.

Shortly before Christmas I picked up Winnie at her home, and we drove to Washington to visit my sister. Winnie and I decided to get married right away. I called my folks at Latrobe. They gave their approval and decided to come to the wedding. Winnie’s parents weren’t keen on the idea, but that didn’t stop us.

We went to the courthouse to get our license, and the clerk asked Winnie how old she was.

“Twenty,” she said.

I kicked her on the shin.

“I mean, twenty-one,” she said.

“Are you sure?” the clerk asked.

“Yes, sir,” Winnie said bravely. Actually she was just short of 21. We were married in Falls Church, Virginia, on December 20 and then began the tournament circuit as a honeymoon. We started our new life on a shoestring in 1955. Under PGA rules I was ineligible to accept prize money from PGA-sponsored tournaments until I had served six months’ probation. But I picked up $750 in a special pro-amateur competition at Miami, then went to Panama and tied Roberto de Vicenzo for second in another non-P.G.A event, collecting $1,300.

This was our stake. Winnie and I picked up the winter tour on the Pacific Coast and bought a trailer to be hauled around by my secondhand 1952 car.

We pulled that trailer all the way across the United States on the tour. In St.Petersburg, Florida, we bought a bigger trailer and headed for home. Near the end of the journey I decided to take a shortcut over a mountain. On the steepest slope, we got near the top and couldn’t make it. I had to back the big trailer down and start again. Winnie got scared and walked to the top. When we finally got over, the very steep downgrade was almost too much for us. With brakes of both the car and trailer screeching and smoking, we somehow reached the bottom of the mountain safely. After we had made it the rest of the way to our backyard in Latrobe, I told mother, “Sell that thing. I never want to see it again.”

I won enough money in non-sanctioned tournaments to keep our heads above water until my six-month probation was up. Since then the tour has been good to me. My money winnings have ranged from about $10,000 that first part year to $42,607 in 1958, when I was the national leader. Last year I didn’t putt well and fell back to fifth with $32,462. This year, with almost $50,000 already won by late May, I have a good chance of reaching $100,000, which would be more than any man ever won in PGA tournaments. Ted Kroll holds the record — $72,835 in 1956.

Three years ago Winnie and I built a white ranch house overlooking the Latrobe Country Club. There is more than an acre of romping room for our two little girls — Peggy, 4, and Amy, almost 2. I’m strictly a home man, and I generally play my best golf when the family is with me. When they can’t be, I take breaks from the tour and go back to Latrobe. Usually I play six or seven tournaments and then skip two. I find these little breathing spells good for my game.

I have two main hobbies — bridge and flying. The Latrobe Airport is only about a mile from my home, and I have close to 100 hours of solo flying to my credit. I’m looking forward to the day I buy my own plane and can sky-hop between tournaments.

On the golf course, I’ll admit, I am a bold player, but the tour has taken away much of my early brashness. As a freshman pro, I felt I could beat anybody. I played like a pirate, going for the pin every time regardless of the consequences. I still do that most of the time — particularly when I feel I have at least a 50-50 chance of making the shot — but I don’t gamble when a miss can be very costly.

All in all, I think the biggest improvements in my game during the first months of this year were steadier putting and better concentration.

Now that I’ve won my second Masters, I notice that some people are comparing me with Ben Hogan and Sam Snead. I’m not like either of them. I figure I am a power hitter like Snead, with a swing that has needed little or no overhauling. But Sam has the greatest natural talent I ever saw. His ability is such that he can win tournaments without concentration or extra effort. All he has to do is swing away.

Hogan, on the other hand, is self-made — the product of his own relentless determination. He is the coldest, sharpest calculator I have ever seen on a golf course. I get intent at times myself, but often I shrug it off and say, “What the heck — it’s just a game.”

Although Hogan and Snead are nearing 50, both are still threats in a tournament such as the National Open this week. However, I believe the main competition at Cherry Hills will come from younger men who have been active on the 1960 tour.

Bill Casper, the defending champion, is more than just a great putter — the label some people have hung on him. He is a fine all-around player. Dow Finsterwald, one of my closest friends, is always a threat. This is a cold business with him, and he approaches it like a machine. Ken Venturi is a classic player, capable of reaching brilliant heights. Mike Souchak is the strongest man in golf and is hard to beat when he is rolling, but he is inclined to be streaky. Gene Littler is solid as an oak, with wonderful natural talent, but has seemed to lack inspiration. Art Wall and Bob Rosburg have proved they can be top players despite their unorthodox baseball grips.

In my opinion, this is the select little group I’ll have to overcome if I’m to keep my grand-slam attempt alive by winning the U.S. Open. I have one wish for this tournament. I just hope things will work out so that I can come down to the final two holes needing one birdie to tie and two to win.

Eight days after this story was published in the 1960 Post, Arnold Palmer won the U.S. Open. At the British Open in July, he came in second — by a single stroke — to Kel Nagle, ending his chance at the modern-day Grand Slam. (To date, the challenge of winning the four major PGA tournaments in a single season remains a unicorn for professional golfers, who credit Palmer with the concept.) In October, Palmer was voted 1960’s PGA Player of the Year, receiving 1,088 of the 1,217 votes cast by professional golfers and the media.

The international golf star gained 95 professional and 26 amateur wins before he retired at age 76 — nearly three more decades of golf than “Pap,” his father and golf teacher, had predicted for him in 1960. Palmer died Sunday at the age of 87.