The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Still Works for You

Rights can be precarious things. In the political present, states pass laws that conflict with Supreme Court decisions, and issues of individual rights come into question at traffic stops and borders. Remarkably, rights were even less certain in the 1960s. That’s one reason that we stop to remember that President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Acts into law 55 years ago today. Despite this being a monumental piece of legislation, people are often confused about what it means and what protections it affords. The Act impacts everything from voting to schools to where court cases are heard and beyond. Let’s take a look at some of the most important pieces of the act, as well as the updates made in 1968 and 1991.

President Kennedy’s 1963 Civil Right Address (Uploaded to YouTube by JFK Library)

President John Kennedy had proposed the act in 1963, and Representative Emanuel Celler of New York introduced it, but a filibuster in the Senate ground its passage to a halt. After Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson made it a priority to drive the bill forward, and signed it upon its passage on July 2, 1964. The broad idea of the 1964 Act is fairly simple to grasp: It aims to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places. This larger concept is tackled in 11 titles under the act. In simple terms,

- Title I requires that voting rules and procedures be applied equally to all eligible voters.

- Title II forbids discrimination in “public accommodations” like movie theaters, hotels, and restaurants (though it didn’t go so far as to include private clubs).

- Title III enshrines access for all to public facilities.

- Title IV desegregated public schools and also empowers the Attorney General to file suits to enforce desegregation.

- Title V expanded the S. Commission on Civil Rights, which had been created by the earlier Civil Rights Act of 1957.

- Title VI bans any discrimination by programs that receive federal funds.

- Title VII was constructed to create equal opportunity practices for employment.

- Title VIII was geared toward statistics, making it mandatory to track both voter registration and voting data in places decided upon by the Commission on Civil Rights.

- Title IX (not to be confused with the more-famous Title IX of the Education Amendments Act, which pertains to college sports and beyond) eases the movement of civil rights cases from state courts to federal courts, a rule that was applied because discrimination-based proceedings had a difficult time getting heard in certain states.

- Title X authorized the creation of the Community Relations Service, which is part of the Department of Justice; the service works to mollify community tension and conflicts brought out by acts related to discord between groups in which race, etc. may have played a part.

- Title XI affords protection for defendants of criminal contempt in certain permutations of cases arising from any of the other articles.

No piece of legislation is perfect, but overlooked or unexpected divergences from earlier laws can be corrected or updated in later bills. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 made efforts to address civil rights for Native Americans, as well as tackling housing discrimination in the Fair Housing Act (which is composed of Titles VIII and IX in the text). Labor was addressed in the Civil Rights Act of 1991, guaranteeing the right to a jury trial in cases of discrimination claims while also strengthening the ability of women to sue for sexual harassment or discrimination at work.

Today, inequalities still exist, but the 1964 Civil Rights Act remains one of the most comprehensive attempts to address them. Its passage made possible subsequent legislation, like the Americans with Disabilities Act and the more recent protections afforded to LGBTQ citizens. Our current cultural moment finds us still dealing with fractured communities and the pains of the past. By recognizing these inequities and attempting in some small way to mitigate them, steps like the Civil Rights Act keep us on the path that Kennedy envisioned when he said, “We cannot say to 10 percent of the population that you can’t have that right; that your children cannot have the chance to develop whatever talents they have; that the only way that they are going to get their rights is to go in the street and demonstrate. I think we owe them and we owe ourselves a better country than that.”

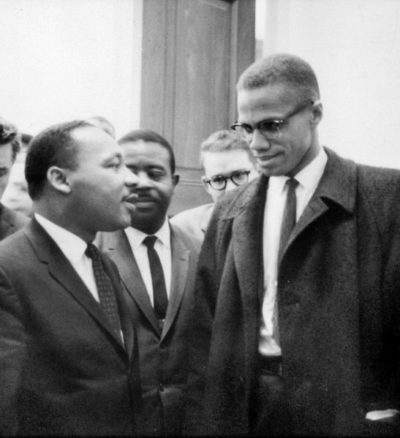

Featured image: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others observe. (Photo by Cecil Stoughton of the White House Press Office; Wikimedia Commons)

Comedians in the White House: Our Favorite Jokes by Presidents

“Thanks, folks. I’m here all this term.”

The president of the United State is supposed to represent the people of the country. And since we Americans have a sense of humor that is strong as it is broad, it’s not surprising that presidents can occasionally crack up their audiences.

Here are a few chuckles from our Chief Executives.

John Adams

on the legislature

“In my many years I have come to a conclusion that one useless man is a shame, two is a law firm, and three or more is a congress.”

Abraham Lincoln

of a political foe

“He can compress the most words into the smallest idea of any man I ever met.”

Theodore Roosevelt

on corruption in Congress

“When they call the roll in the Senate, the Senators do not know whether to answer ‘present’ or ‘not guilty.'”

Calvin Coolidge

to a woman sitting next to President Coolidge at a dinner party told him she’d bet a friend she could get at least three words of conversation out of him.

“You lose.”

Franklin Roosevelt

on being informed by an aide that Eleanor Roosevelt (who was conducting a fact-finding tour of a penitentiary) was “in prison.”

“I’m not surprised, but for what?”

John F. Kennedy

“I was almost late here today, but I had a very good taxi driver who brought me through the traffic jam. I was going to give him a very large tip and tell him to vote Democratic and then I remember some advice Senator Green had given me, so I gave him no tip at all and told him to vote Republican.”

Lyndon B. Johnson

addressing a Marine who said, “Mr. President, this is your helicopter over here.”

“They’re all mine, son.”

Jimmy Carter

on a late resurgence of his popularity

“My esteem in this country has gone up substantially. It is very nice now when people wave at me they use all their fingers.”

Ronald Reagan

on other politicians

“I have left orders to be awakened at any time in case of national emergency — even if I’m in a Cabinet meeting.”

Bill Clinton

describing the White House

“Being president is like running a cemetery: you’ve got a lot of people under you and nobody’s listening.”

George W. Bush

“No matter how tough it gets, however, I have no intention of becoming a lame-duck president. Unless, of course, Cheney accidentally shoots me in the leg.”

Barack Obama

on his name

”Many of you know that I got my name, Barack, from my father. What you may not know is Barack is actually Swahili for ‘That One.’ And I got my middle name from somebody who obviously didn’t think I’d ever run for president.”

Donald Trump

on wife Melania Trump’s Republican National Convention speech

“The media is even more biased this year than ever before — ever. You want the proof? Michelle Obama gives a speech and everyone loves it — it’s fantastic. They think she’s absolutely great. My wife, Melania, gives the exact same speech, and people get on her case.”

Featured image: Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and George W. Bush in 2013 (Pete Souza, White House photo)

Falling for Jackie Kennedy

This is the sixth installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

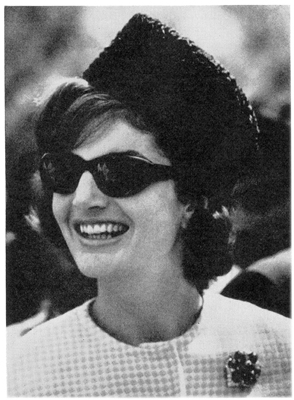

Hollywood couldn’t have dreamed up two better characters than John and Jacqueline Kennedy to portray America’s ideal, romantic couple. She was elegant, poised, and incredibly well dressed. He was the newly elected president of the United States. Young, sophisticated and good looking, they seemed like the polar opposites of the previous residents of the White House, Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower. The Kennedy’s attractiveness quotient rose even higher just two weeks after the election when Jacqueline gave birth to a son.

Many Americans only got their first look at Jackie during the inaugural ceremonies. She’d remained at home during the campaign under her obstetrician’s order, though she was still giving interviews, taping TV commercials, and writing a weekly newspaper column called “Campaign Wife.”

In the following months, Americans read about the dazzling receptions she hosted, how she put international visitors at ease with her command of French and Spanish, and even got on the good side of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. Newspapers and magazines also ran stories on Jackie’s wardrobe and her French-influenced look. Copies by several domestic designers soon appeared on American women across the country.

But Jackie made her most memorable impression as first lady in 1962, when she conducted a televised tour through the recently refurbished White House.

The makeover had been sorely needed. As the Post reported in 1963 (“How Jackie Restyled the White House”), President Truman had ordered massive renovations to the White House’s structure in 1945 to prevent the building from collapsing. But the interior design had been an afterthought, entrusted to a hotel contractor who gave the rooms a bland, institutional look. One Washington reporter wrote, “The White House is safe, all right, but it has completely lost its charm. The restoration took the heart out of the building…Now it has no more appeal than the Pentagon.”

Arriving at the White House, the Kennedys discovered most of the furnishings dated back only as far as 1902. The paintings were all forgettable works that previous presidents hadn’t bothered to take with them when they left.

What Jackie proposed was more than just a refurnishing. Her intention was to build a collection of White House furnishings that would reflect the long heritage of American design. Under her direction, the Executive Mansion acquired 500 items of furniture and art. Some were former White House furnishings that she bought back from private ownership. Many other items came from wealthy collectors, but several were donated from average Americans who offered up their antique silverware, wallpaper, and chamber pots. When completed, the collection was protected by a law, proposed by Jackie, that would forbid the removal of any items from the White House.

The tour of the completed project was televised on February 14 when Jackie showed the new acquisitions and explained how each room was furnished in the style of a different era. The Lincoln room, for example, contained only furniture of the Civil War period and included Lincoln’s own portrait of Andrew Jackson and a table purchased by his wife, Mary. Jackie was seen that night by over 80 million Americans.

Jackie made her most enduring impression when she was no longer first lady. She remained in the public eye from the death of her husband right up to his burial at Arlington Cemetery. Throughout that time, she displayed a fortitude and courage that few had suspected in her.

Looking back at articles about her in the Post, it’s surprising to see how good a job she did as first lady even though it was a job she never wanted. Interviewed for the Post by an old friend (“An Exclusive Chat With Jackie Kennedy”), she admitted to a chronic shyness. “I can’t stand being out in front. I know it sounds trite, but what I really want is to be behind [John] and to be a good wife and mother.”

It wouldn’t have surprised John Kennedy. His wife had always impressed him with her quiet strength. Years earlier, he told a friend, “My wife is a shy, quiet girl, but when things get rough, she can handle herself pretty well.”

It’s no surprise that even today, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy remains an icon in American history.

A Very Eligible Politician

This is the first installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.” Click here to read part two, “Kennedy on the Campaign Trail.”

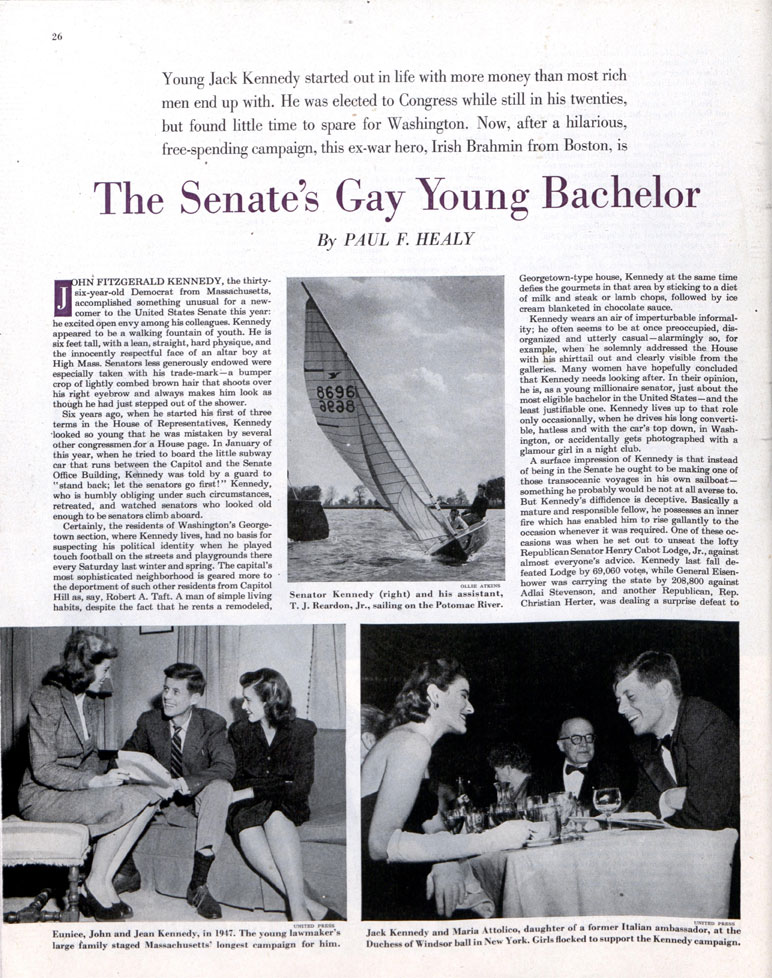

The first time the Post took notice of John F. Kennedy, he was still a very junior senator from Massachusetts. It was unusual for the magazine to run a feature article on a senator, particularly one as young and inexperienced as Kennedy. But Paul F. Healy, author of “The Senate’s Gay Young Bachelor,” found Kennedy particularly newsworthy.

For one thing, he was a fresh face in the senate, idealistic and energetic. The 36-year-old senator had “that look of youth,” Healy wrote. “He was six feet tall, with a lean, straight, hard physique and the innocently respectful face of an altar boy at High Mass.”

Throughout his career, his youthful looks prevented many colleagues and foreign leaders from taking him seriously. His appearance and demeanor could prove a handicap, as on the day he was boarding the subway car that ran between the Capital and the Senate Office Building. As he stepped into the car, the subway guard told him, “Stand back; let the senators go first!” The anecdote says much about Kennedy’s youthful looks, as does the fact that he complied and waited for the other senators to board ahead of him.

But his appearance proved a strong advantage among women voters. “During the campaign,” Healy wrote, “every woman who met Kennedy wanted either to mother him or marry him. At first glance, he looked a little lonesome, and in need of a haircut and perhaps a square meal… Many women have hopefully concluded that Kennedy needs looking after. In their opinion, he is, as a young millionaire senator, just about the most eligible bachelor in the United States—and the least justifiable one.”

On the date that line appeared in the Post, Kennedy had less than 100 days of bachelorhood left. He was already engaged to Jacqueline Bouvier, but the couple delayed the announcement of their wedding until the after the bachelor story ran.

Healy was also fascinated by Kennedy’s background: here was a young man who had grown up in comfort and privilege but who had requested combat duty in the second world war. Due to his nautical experience, Kennedy was given command of a torpedo boat in the South Pacific. On a moonless night in August, 1943, a Japanese destroyer ran over Kennedy’s PT boat, cutting it in two. Kennedy led the survivors on a swim to a distant island, helping one wounded man to safety by holding the strap of the man’s life vest in his teeth as he swam. Kennedy’s citation for “extremely heroic conduct,” says, “During the following six days, he succeeded in getting his crew ashore, and after swimming many hours attempting to secure food and aid, finally effected the rescue of his men.”

According to Healy, Kennedy’s war experiences had made him “more serious.” Though still young, he was “basically a mature and responsible fellow [who] possesses an inner fire which has enabled him to rise gallantly to the occasion whenever it was required.” He also had the sort of character that made people want to do something for him. This compelling appeal might be the earliest reference to what was later called the Kennedy “charisma.” The term was applied to the president so often that many people began to wonder if it had been made up just for Kennedy. By the time he was in the White House, Kennedy’s critics were heartily sick of hearing about charisma. They argued that it was no more than superficial charm, and that Kennedy’s political success could all be attributed to the judicious application of his father’s fortune.

Kennedy made fun of the accusation that his father had bought his victories. Speaking at a Washington dinner during his 1958 campaign, Kennedy pulled from his pocket a “telegram,” which he said was sent from his wealthy father, former ambassador to the United Kingdom Joseph Kennedy, who was sunning somewhere on the French Riviera. He told the attendees, “I have just received the following wire from my generous daddy. It says, ‘Dear Jack, don’t buy a single vote more than is necessary. I’ll be damned if I’m going to pay for a landslide.'”

Kennedy could afford to joke about his father’s influence because it was widely known how hard he worked for each political victory. Healy’s article is the first of many that would repeat the same story: Kennedy was a relentless campaigner. He rose early, traveled long, gave numerous speeches that rarely repeated each other, shook any hand he could, and retired at night with time enough to get four hours’ sleep.

It was an impressive performance for someone who, until seven years earlier, had intended to be a journalist. His father had groomed his oldest boy, Joe, Jr., for a political career and expected him to keep winning until he entered the White House. But after Joe died in World War II, Joe’s expectant look turned to John.

For a very brief period, John Kennedy worked for Hearst newspapers, and was looking forward to an intellectual’s life of researching and writing history. But then a vacancy opened up in the Massachusetts’ 11th district. Kennedy ran and won. He may not have loved politics, but he was always competitive and he loved winning.

This early decisive victory was the start of a trajectory that would take him from congressman to president in just 14 years.

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

Kennedy on the Campaign Trail

This is the second installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.” Click here to read part one, “A Very Eligible Politician.”

We tend to remember him as president; it’s hard to remember that shortly before he ran for office, John F. Kennedy was as a relatively unknown young senator, and that once he was in the race, he faced serious obstacles in his bid for the presidency. But that was his situation in early 1960, when Post reporter Stewart Alsop listed ten reasons Kennedy might not win his party’s nomination.

The first was religion. No Catholic had ever successfully run for president, and many Americans in 1960 wondered if the country was ready for a Catholic in the White House. Throughout the presidential campaign, Kennedy worked hard to convince voters his religion would not shape his executive decisions. Yet the doubts persisted. In “Campaigning With Kennedy,” Post reporter Beverly Smith wrote of being present when a reporter read a statement from protestant ministers suggesting Kennedy’s decisions might be shaped by the Vatican.

Smith could see Kennedy working hard to control his anger and return a civil response. “We saw the flush spread upward from his throat into his tanned, suddenly tense face.” But when Kennedy responded, it was in a calm, controlled, but icy voice. “Our Constitution is very clear on the separation of church and state; I have been very clear—and precise—in my commitments to that Constitution, not merely because I take the oath which is taken to God but also because I believe it represents the happiest arrangement for the organization of a society.”

He went on to remind his questioners the Constitution forbade setting any religious qualification for the presidential office.

Another obstacle was Kennedy’s family background. His father, Joseph P. Kennedy, had made a quarter of a billion dollars as a stock market speculator and liquor importer (though never in bootleg alcohol, despite the rumors.) Along the way to acquiring his fortune, Joseph had made “a whole slew of enemies,” which John inherited.

He also inherited the suspicion that Joe Kennedy would buy his son’s election to the White House, and then tell John how to run the country. But from very early in the campaign, John asserted that he would not be shaped by his father’s more conservative politics, wrote Smith. “When the older Kennedy is moved to express his political views, which are rather to the right of his friend Herbert Hoover’s, his son is apt to break in with, ‘We’ve heard the former ambassador’s views, now let’s get on with our business.’”

Kennedy’s campaign benefitted from the powerful support of his siblings. His four sisters and two brothers had worked hard in his Massachusetts campaigns for Congress and the Senate. When he announced in 1959 that he intended to run for president, they pooled their money and bought him a private airplane, complete with sleeping quarters. The gift plane, wrote Stewart Alsop, showed Kennedy’s opponents what his Massachusetts challengers had already learned, “When you run against Jack, you aren’t running against just one Kennedy, but the whole tribe.”

“His two brothers,” Alsop continued, “are already working hard for him. They are Bob Kennedy, nationally known for his work as counsel… investigating racketeering in the labor-management field; and the youngest brother, Ted, a husky ex-footballer and recent graduate of the University of Virginia Law School.”

Smith believed John Kennedy’s greatest family asset, though, was his wife, Jacqueline. “Reporters covering the Kennedy campaigns wondered at first how a very shy, very beautiful, very young woman would go down with the voters as a potential first lady. By the time the West Virginia campaign ended, they were unanimously convinced that the beautiful Jackie was a major Kennedy political asset.”

Another obstacle in Kennedy’s campaign was his youth. Many voters refused to believe a 43-year-old man without executive experience could run the country. But while his youth lost him the senior vote, it gained him supporters in the younger generation. Smith observed, “In each state I visited with Kennedy, I was impressed by the number of youthful volunteers working ardently for his cause… [They reminded me] that Theodore Roosevelt entered the White House at forty-two, Washington took command of the Continental Army at forty-three, and Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence when he was thirty-three.”

The young voters of 1960 who rallied to Kennedy’s cause had been born in the Depression, grown up during a world war, and reached maturity as America entered a seemingly endless cold war with a possible risk of nuclear war. By the time the 1950s drew to a close, they had grown tired of the continuing crises. They wanted a freedom from worry and a world of opportunity in which they could make their mark. And, like so many of their elders, they wanted to make the world a better place. Kennedy spoke directly to these yearnings, but in an unexpected manner.

“When he gets down to the substance of his speeches, he preaches a hard gospel,” Smith observed. “In politics this is unusual, if not unpalatable. American voters are used to being told that they are the salt of the earth and there’s a good time coming. Kennedy’s message is quite different. He does not flatter or talk down.” To illustrate, Smith offered a typical quote from one of Kennedy’s speeches: “Ours is a great country, but we can make it a greater country. It is powerful, but we must make it more powerful. I ask your help. I promise you no sure solutions, no easy life. The years ahead, for all of us, will be as difficult as any in our history. There are new frontiers for America to conquer—frontiers of the mind, the will, the spirit of man.”

Such words had an unusual effect on the crowds. While Kennedy told them they had better prepare for harder work and stricter self-discipline, Smith could see puzzled uneasiness on their faces. But Kennedy argued his point with facts and earnest vitality. When he finished, there would often be a moment of intense silence before a rising ovation began.

Smith’s conclusion reflected the desire for change many Americans felt at the start of a new decade. “It is not that Kennedy has ‘changed’ his audience. But most of us have, beneath our outer optimism, a troubled feeling that we have failed to live up to the greatness of our heritage. It is this chord which Kennedy strikes and brings to life.”

It was a chord that would resonate long after Kennedy was gone.

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

Rethinking Kennedy’s Camelot

This is the third installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

In the years following the death of President Kennedy, many people often spoke of his presidency as an idyllic time. Picking up on Jackie Kennedy’s reference to the Richard Burton-Julie Andrews musical, they dubbed those pre-assassination days as “Camelot,” a noble, idyllic but ultimately doomed kingdom.

It is easy to imagine such a bright, innocent time existed on the far side of the tragedy. But was the country truly different before Kennedy’s assassination?

Excerpts from several Post articles in 1963, prior to the president’s death, demonstrate that in truth America was already in the midst of troubling times that little resembled the idyllic innocence of “Camelot.”

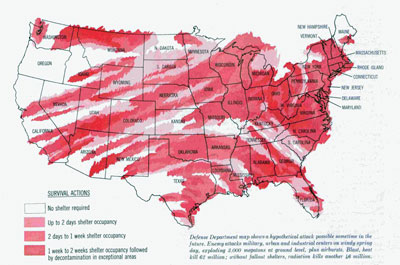

In March of 1963, the Post ran “Survival of the Fewest,” which informed readers that the U.S. could not protect them from a possible nuclear attack. Government strategists had calculated that nuclear weapons from a Russian attack would directly kill 21 million Americans. Radioactive fallout would kill an additional 13 million, they estimated, unless citizens had access to bomb shelters.

At the time of the article, the Kennedy administration had already called on the nation to construct enough fallout-shelter space for 240 million Americans over a five-year span, yet few Americans took action to protect themselves from nuclear holocaust. Only a small fraction of the necessary fallout shelters were built, because homeowners found them expensive, inefficient, and hard to assemble. Radio stations continued to regularly test their connections with the CONELRAD civil defense system, and school children still huddled under their desks when the town siren was tested, but by 1964, demand had disappeared and one California dealer couldn’t even give the shelters away.

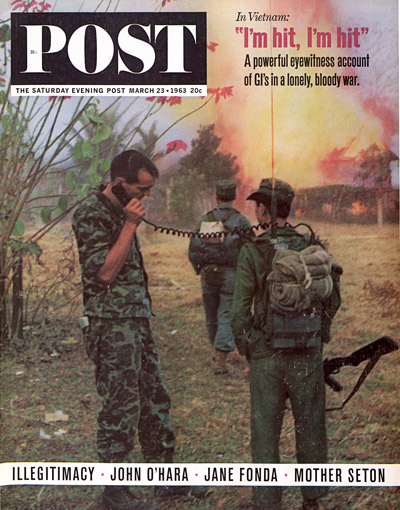

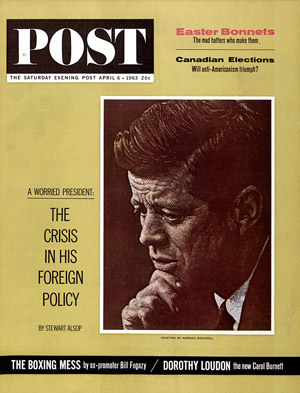

At the same time that Americans worried about Russia’s nuclear arsenal, they learned that the U.S. was getting pulled into yet another distant confrontation with Communism. In September of 1963, the Post reported in “The Edge of Chaos” that, “President Kennedy, convinced that a Communist takeover of South Vietnam might mean the fall of Southeast Asia, has repeatedly promised to defeat the guerillas that dominate much of the country. He has backed up his words with a 16,000-man U.S. force in Vietnam—more than 100 have lost their lives—and with $1.5 million a day spent on the war.”

© Curtis Publishing Co.

“But,” the article continued, “the spectacle of American-trained troops using American weapons to raid Buddhist temples made clear one fact that U.S. officials have long tried to evade: No matter how much the United States supports the unpopular regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, this regime’s chances of victory over the Communists are just about nil.”

Ever since World War II, the country had been opposing communist expansion, first in Eastern Europe, and then in Central America, Africa, and Asia. Its principal weapons in this fight were money, arms, and military supporters. But by the 1960S a new element had been added to the Cold War, instigated partly by a novel that had been serialized in the Post.

In 1958, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer wrote The Ugly American out of their anger at seeing American prestige dissolving in Southeast Asia. They were outraged by the way American diplomats and advisors were “ doing the wrong thing, or doing the right thing the wrong way, or just doing nothing.”

Serialized in five parts from October 4, 1958 to November 8, 1958, their novel about a fictional diplomat in Asia drew a generally negative response from government officials. The State Department dismissed the book as a “distortion,” and it was criticized by President Eisenhower and several senators. But after Senator John Kennedy read the book, he bought copies for the entire senate, and the government began to respond.

In “The Ugly American Revisited,” [June 4, 1963], Burdick and Lederer reported, “American foreign aid is now a much more practical, tough-minded proposition than it was five years ago.”

In their article, the authors also admitted they’d been stunned by the public response to their book, which had sold nearly 4 million copies. Even more startling were the thousands of letters from individual Americans asking, “What can I do?” To the authors, this response reflected a deep concern among Americans about their position in the world. “They are often confused, often angry, but always willing to learn. They possess a quiet awareness of the deadly peril in which we live. And they are, more important, ready to ‘do something about it.’”

What many of them did about it, wrote Burdick and Lederer, was volunteer for the Peace Corps, which Kennedy had founded as one of his first acts, in 1961, and which had been a resounding success. “Indeed, it is quite without parallel in history,” they wrote two years later. “It is a source of great pride to us that a majority of Peace Corps volunteers indicated that their first interest in foreign affairs came from reading ‘The Ugly American.’”

Burdick and Lederer saw a new mood spreading through the country. “Americans, in both high and low places, are willing to be critical of themselves without falling into despair. On balance, America is surely moving with greater energy, more skill and more confidence in its overseas operations.”

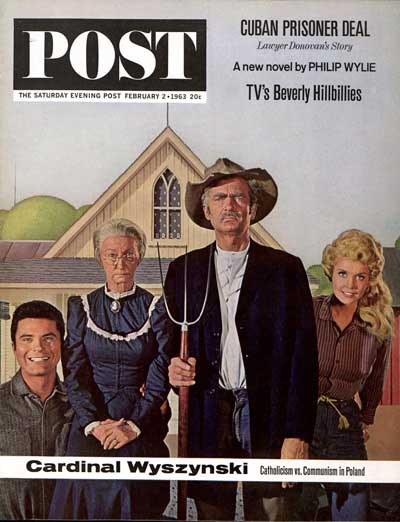

But the America of 50 years ago could also be characterized by its entertainment, some of which did not especially resonate with the nobility of the knights of the round table. The most popular television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, was a prime target for reviewers’ abuse (the Post declared it was “deliberately concocted for mass tastelessness.”)

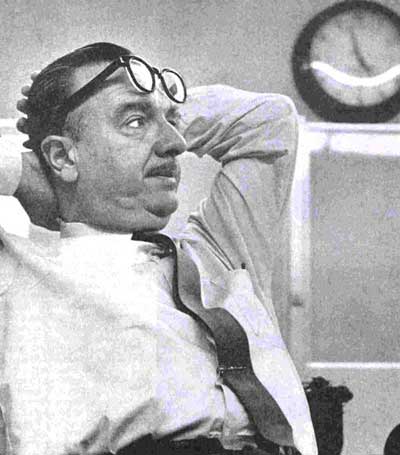

But television in 1963 also had the sedate and reliable Walter Cronkite, whom the Post profiled in March of that year. Cronkite was still relatively young, just a few months older than President Kennedy. But he, too, was a veteran, having reported World War II from a B-17 and with the 101st Airborne division.

“He has conversed with queens and dictators,” wrote Post author Lewis Lapham, “lived under the polar ice for a week, seen governments fall and atomic bombs exploded.”

And he was now the trusted anchorman of the CBS evening news, a post he was to hold for another 18 years.

In that distant time, before Americans preferred their news heavily seasoned with entertainment, Cronkite won the loyalty of viewers with his fairness and adherence to facts.

“Cronkite’s detractors usually criticize him for this unwillingness to advance an outspoken opinion. They complain that he is too polite, too bland, too dull,” wrote Lapham. “He considers the criticism unreasonable. ‘Probably if I made a few more acerbic remarks, I might win a few more viewers,’ he concedes, ‘but I don’t feel like being funny with the news; I don’t think that’s my place.’”

Just a few months after Lapham’s article was published, Cronkite became part of the permanent memories of a generation of Americans when he delivered the news of President Kennedy’s assassination.

“If, in the search of our conscience we find a new dedication to the American concepts that brook no political, sectional, religious or racial divisions,” Cronkite observed following Kennedy’s funeral, “then maybe it may yet be possible to say that John Fitzgerald Kennedy did not die in vain.”

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

How the Early 1960s Looked to Americans

This is the fifth installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

April 6, 1963

Scroll below for a decade of vintage ads

and Post art from 1953 to 1963.

(Click on images to expand.)

The decade began with a more promising look than the last three: The 1930s had started with the Depression, the 1940s with a world war, and the 1950s with the Korean conflict and the threat of nuclear war.

But the 1960s began with the election of a young, optimistic president who spoke of new opportunities. “Change is the law of life,” John F. Kennedy said, and in his inaugural address, he talked about “a new generation,” “a new alliance for progress,” “a new endeavor,” and “a new world of law.”

Such words were welcome to the younger generation, which had grown up in the shadow of war. They were eager for change, which began as Kennedy took office. But it did not begin with Kennedy alone. The changes that reshaped the country in the 1960s came from developments that started even before Kennedy took office.

In February 1960, months before Kennedy’s election, four black students sat down at a “whites-only” lunch counter and asked for service. When denied, they waited quietly and went home when the store closed. The next day, they were back with more students. It was not the first sit-in, but this one caught the attention of the press. The students eventually succeeded in pressuring the store to integrate its lunch counter, which encouraged black students in other college towns to stage their own sit-ins. The era of group protests for civil rights had begun.

On May 10, 1960, The New York Times ran a brief article announcing FDA approval for Enovid for use as an oral contraceptive. Freeing women from the fear of unwanted pregnancy, “the pill” was on its way to revolutionizing the sex life of the country.

On March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed an order establishing the Peace Corps. Within three months, it had received 11,000 applications from Americans. By 1963, over 7,000 Americans had put their lives on hold for two years to bring technical assistance and goodwill to underdeveloped nations. Today, almost a quarter-million Americans have served in the Corps.

Two months later, President Kennedy ordered 400 Green Beret soldiers to South Vietnam. These “special advisors” were only intended to train the republic’s solders fighting communist guerillas. Kennedy hoped it would be a brief, successful intervention by the U.S. But by the next year, the number of U.S. troops had grown to 50,000. Before the decade was over, America had sent more than half a million soldiers to Vietnam and, coincidentally, created an immense anti-war movement at home.

In September of 1962, Rachel Carson published a book about chemical pesticides’ effects on wildlife. Her Silent Spring led to a Federal inquiry and new restrictions on the use of these chemicals. But the book can also be credited with helping start the modern environmental movement.

In 1963, Betty Friedan proposed writing an article about the unhappiness and discontent among American women. When no magazine accepted the article, she wrote a book on the subject, The Feminine Mystique. Many historians believe it launched the new wave of feminism, which would change the relations between the sexes in our country.

Few Americans could be faulted for not recognizing these early signs of massive change. It was easier to see changes closer to home. One of the most noticeable ways in which life was different in the 1960s was the manner in which many American could spend their free time.

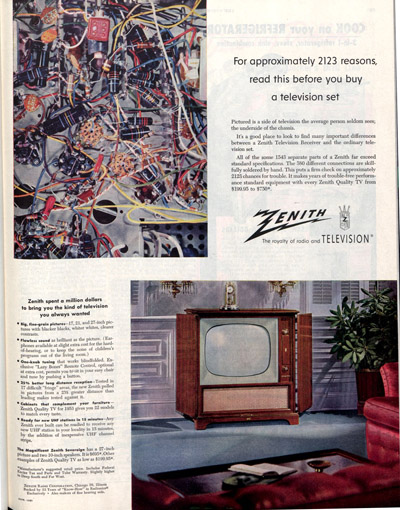

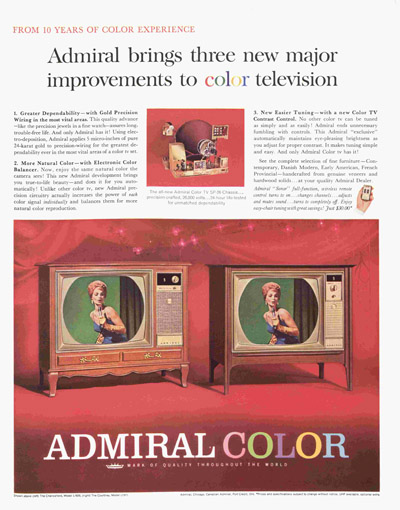

At the close of World War II, they had relied on radio and motion pictures for entertainment; network broadcasting of television shows was virtually nonexistent. Fifteen years later, Americans were spending five hours every night in front of their TV sets. Manufacturers were starting to push color sets, even though major networks didn’t fully switch to color broadcasting until 1967.

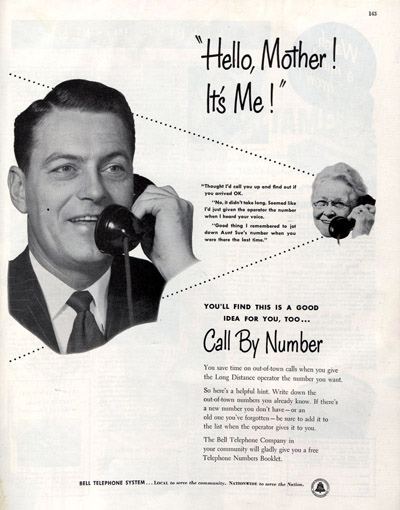

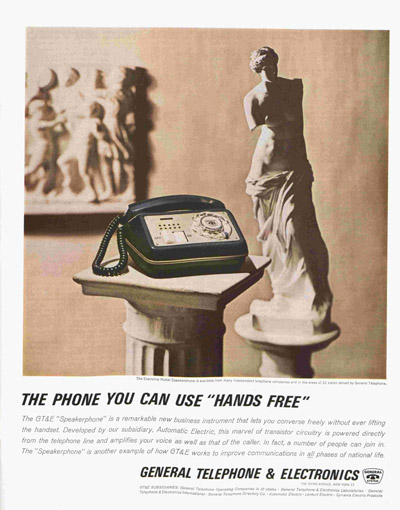

When they weren’t in front of the television, Americans were spending more time on the telephone. The modern phones of 1963 were portable (i.e., no longer fastened to the wall), used buttons instead of rotary dials, and even had speakers so you could talk on the phone with both hands.

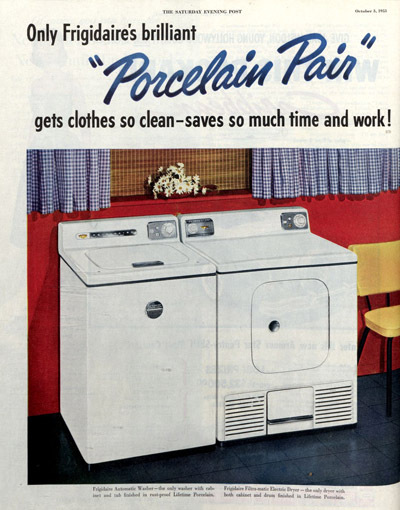

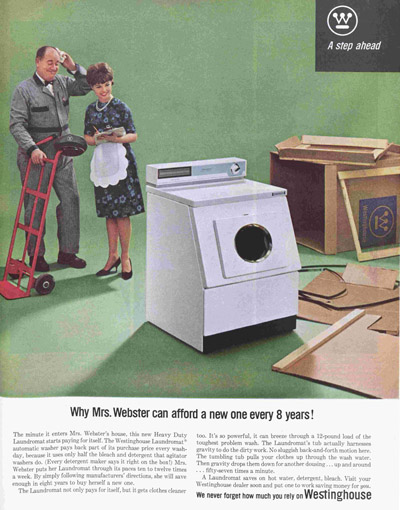

Most Americans knew little about the schools of modern design, but they could tell that their washing machine, which looked so up-to-date in 1953, now looked dated. The newer models were more compact, more efficient, and available in pink!

Frigidaire Washing Machine

General Electric Washing Machine

Westinghouse Washing Machine

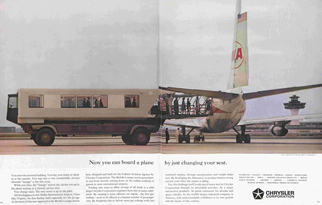

Transportation was also changing. Flying had once been a luxury only the rich could afford. Now, more and more Americans were crossing the country by air instead of driving the nation’s pre-interstate highway system. Between 1953 and 1963, the annual civilian air traffic rose from 8 million hours to 15 million.

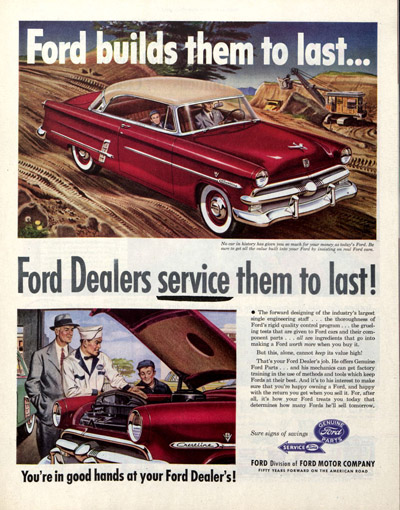

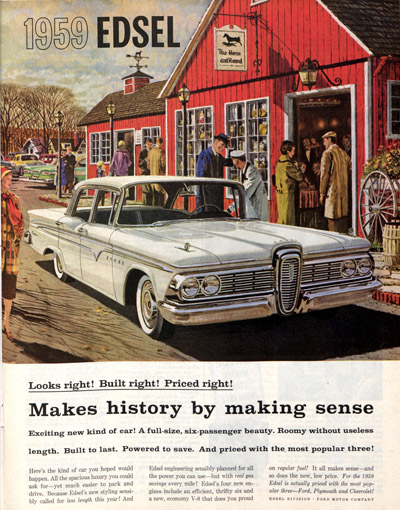

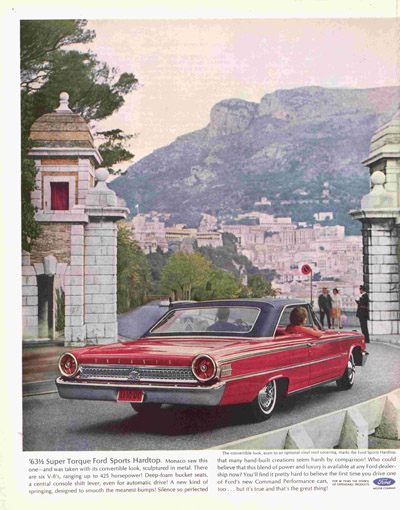

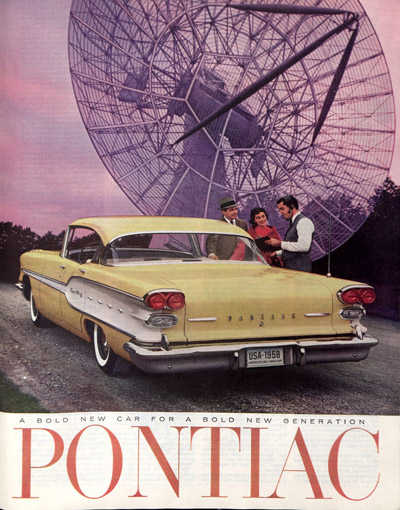

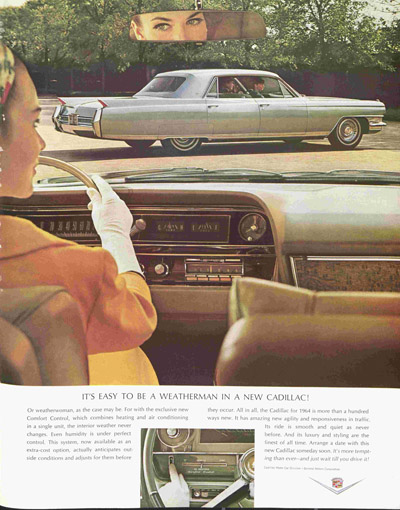

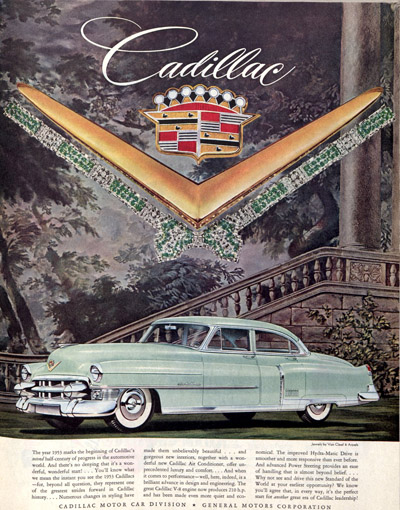

Meanwhile, 94 million American drivers were supporting the nation’s auto industry that turned out over 7 million cars every year. Anyone shopping for a new car in 1963 would have been struck by how much American auto design had changed over the years. The new cars seemed less enthralled with vast chrome grills. They were lower, sleeker, and more aerodynamic. They had lost the corpulent curves and, though still large, they were styled to reflect a modern idea of simple, straight-lined elegance that implied speed even when the car was standing still.

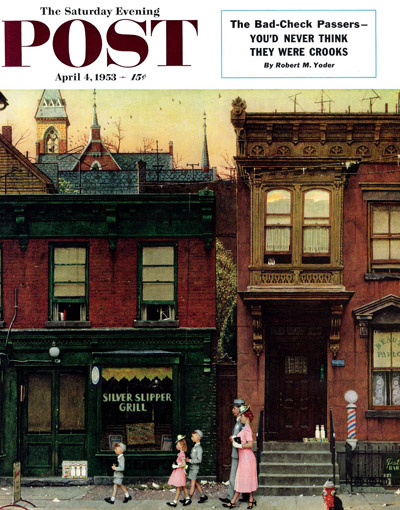

Over 6.5 million Americans would also have seen change in their weekly copies of the Post. Between 1953 and 1963, the illustration style of the magazine became more impressionistic. By 1963, the magazine had changed to meet Americans’ preference for photographic illustration. Most of the covers featured color photos instead of illustration, and many of the articles inside used full-page and color photography.

Once the Post had dictated popular tastes in American entertainment. Now it hurried to catch up with the popular tastes shaped by the new electronic media.

The Saturday Evening Post

The Saturday Evening Post

The Saturday Evening Post

Why Kennedy Still Matters

Why do Americans have such a high opinion of John F. Kennedy? The 35th president completed only three years of his term and left behind a pile of unfinished projects and unraveling plans when he died. So why, in opinion polls over the decades, have Americans consistently ranked Kennedy among our greatest presidents?

At the time of his death, his grand design for a united Europe had recently collapsed. In Southeast Asia, the South Vietnamese president he had been supporting with money and troops had just been overthrown and assassinated. And Americans in 1963 could not have forgotten the failed invasion of Cuba by anti-Castro refugees, which had been launched with Kennedy’s approval.

And then, there were Kennedy’s problems at home. “On the day of his death,” wrote Stewart Alsop (“Was John F. Kennedy A Great Man?” Dec. 3, 1966), “all four of his major legislative objectives–aid to education, the civil-rights bill, Medicare, the tax cut—were hopelessly stalled in Congress.”

But consigning Kennedy’s bills to the ‘defeat’ pile, Alsop argued, would be short-sighted: “The four legislative objectives which were so hopelessly stalled in Congress when he died…are all the law of the land now.” They were passed through the efforts of President Johnson and backed by a wave of public support for the late president’s programs. Without Kennedy’s initiative, these laws might never have been introduced or passed.

Americans of 1963 would have regarded Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis as one of his successes. He had demanded that Russia remove the missile bases it had built in Cuba, and threatened the use of force if they refused. At the time, Kennedy was criticized for risking a nuclear war. But he proved himself to be a tough and tactful negotiator, and by establishing some limited rapport with Soviet premier Khrushchev, Kennedy was able to restart talks to halt the nuclear arms race.

In 1962, the two leaders signed the first test-ban treaty, which bound both nations to stop testing nuclear weapons in the atmosphere. The treaty reduced radioactive fallout in the earth’s atmosphere and slowed the development of bigger bombs. Kennedy was particularly proud of the treaty, which he considered a first step toward nuclear disarmament.

Americans today are more likely to give Kennedy credit for advancing the nation’s space program. After the Russians launched the first satellite (1957) and the first man into space (1961), Kennedy asked Congress to fund a multi-billion-dollar space program. Its goal would be “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth” before the end of the decade. It seemed like an utterly fantastic idea in 1961, but Kennedy’s goal was reached in 1969, with six months to spare.

Kennedy is also given high marks for the Peace Corps, which he launched shortly after entering office. Within a few months, thousands of Americans had volunteer to share their time and technical expertise. In the half century since then, the program has sponsored over 200,000 Americans who have helped improve the quality of life in over 130 countries.

But are the Peace Corps, the space program, and a distant crisis enough to earn Kennedy continued high regard? Perhaps what makes Kennedy admirable today is not what he accomplished but how he inspired. When Joseph Alsop wrote of how Kennedy would be remembered, (“The Legacy of John F. Kennedy,” Nov. 21, 1964), he emphasized how the president, by the example of is character, had introduced a time of “renovation and renewal” for the country.

Of course, Stewart and Joseph Alsop were writing about Kennedy in the days before his many adulterous affairs and his precarious health became public knowledge. These later revelations did much to tarnish Kennedy’s character and caused Americans to reconsider the late president’s judgment and achievements. But with the 50th anniversary of his death, many writers are taking a broader view of Kennedy’s performance as chief executive and distinguishing between his public service and his private life.

In the 1960s, Joseph Alsop had been impressed by Kennedy’s style and outlook, which had so little in common with the “average, day-to-day America in the mid-’60s. No one could have differed more sharply from the good, average American, who watches television in his off-hours, is content if his is a two-car family, and does not mind bulging a bit in middle age.”

America had lost its edge during the complacent 1950s, Alsop believed. “Our wealth and our machines have made us, as a nation, just a bit soft and fat, and most of us do not mind this in the least. But Kennedy minded…[He]…was decidedly repelled by softness and flabbiness.”

Throughout Alsop’s article, you can hear the dissatisfaction and search for a better life that was the spirit the 1960s. It’s the same spirit that Post reporter Beverly Smith described in “The Prospects of Candidate Kennedy” (Jan 23, 1960)—the “troubled feeling that we have failed to live up to the greatness of our heritage.”

Americans, Alsop believed, identified with Kennedy’s focus, energy, and passion for achievement. “The routine, the ordinary, the merely average displeased and bored him,” wrote Alsop. “He wanted to live…meaningfully, to the utmost limit of his powers.”

Kennedy told Americans that a better life, and a better world, was possible, but it would take conviction, hard work, and a courage that, Alsop wrote, was “exceedingly uncommon” in modern America. “For Kennedy, courage, whether physical or moral, was the first and most essential of the virtues.”

Americans elected Kennedy because he showed the intensity, idealism, and courage they wanted in their lives. They were hungry for a sense of achievement after years of caution, stagnation, and continual fear of devastating attacks on the U.S. In this regard, they were not so different from us, which is why the example and the memory of Kennedy still matter.

A Surprisingly Popular Presidency

This is the fourth installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

“I myself believe that he will be remembered as one of the great Presidents.” So wrote Post journalist Joseph Alsop in “The Legacy of John F. Kennedy,” (November 21, 1964), as he considered the late president’s legacy. Kennedy, he asserted, had “courage, energy and common sense, clear-mindedness, practicality, a hearty dislike for slogans of whatever kind, and a flat refusal to admit defeat.”

Such praise seems overdone today, after half a century of investigations into Kennedy’s presidency and personal life. Today, we know he hid the facts of his precarious health from the nation; his many adulterous affairs are common knowledge. We suspect he wanted to assassinate Castro, and we have read of his seemingly reckless actions regarding the Bay of Pigs. Some historians still hold him responsible for our ultimately disastrous involvement in the Vietnam War.

Yet even in hindsight, it’s hard to evaluate a president without considering how his contemporaries viewed him. And a great many Americans in the early 1960s, as we’ve found in Post articles, regarded Kennedy with a limitless admiration. He had charm, humor, intelligence, and unflappable poise.

But there was something more to his appeal.

Although he was a conservative Republican, the Post’s political editor, Stewart Alsop, was just as captivated by Kennedy as his even more conservative brother Joseph, who was actually a personal friend of the president’s. In the September 16, 1961 issue of the Post, Alsop reviewed Kennedy’s first year in the White House (“How’s Kennedy Doing?”)—several months after the president’s disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion. “He had done the impossible. At forty-three he was the youngest President ever elected, and the first Catholic. To do what he had done, he had taken a whole series of breath-taking risks. Often it had seemed that he might lose… But always he had won in the end. Is it any wonder that many of his followers had come to believe in a Kennedy star, to believe that, when the chips were down, Jack Kennedy would always win in the end?”

The next year, Alsop conducted a country-wide survey “to get some notion of how real Kennedy’s popularity is and how deep it goes.” The results of his interviews, which appeared in the Post as “The Mood of America” on September 22, 1962, summed the opinions of 500 voters.

According to the results, Kennedy was maintaining his support. More than half of the interviewees had voted for him, and said they would support him in the next election. Several people who had voted Republican also said they would vote for Kennedy’s re-election. Alsop believed many of these swing voters were people who had overcome their objection to a Catholic in the White House.

Kennedy’s supporters most often described him as “dynamic,” “straightforward,” and “well-educated.’” The chief criticism among those who didn’t support him was, as Alsop expressed it, “He’s rich and knows nothing about the problems of the poor.” The other common objections? “He’s reaching out for too much power”; “He flies off the handle too much”; “Too much family.” This last objection referred to Kennedy’s very politically involved family, including his brothers who served as a state senator and as the nation’s attorney general.

Many of these 500 Americans were also still concerned about the Cold War. Since the end of World War II, America had seen one country after another fall under Soviet rule; some by occupation, as in Eastern Europe, some by invasion, as in Korea.

The Soviet Union seemed to always be one step ahead of the Americans. We didn’t learn the Russians had stolen details of our atomic bomb plans until they detonated their own in 1949. And we only learned how far their space program had advanced after they had successfully launched the first man into space. Russia was training revolutionaries who were now stirring insurrections in Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia. And now their power had spread to Cuba, where the Russian army was pointing missile launchers at America, just a few hundred miles away.

But according Alsop’s interviews, “only one in five of the interviewees thought there was a ‘big’ danger of war.” Many believed “there would be no war ‘so long as we remain strong.”

Still, many Americans worried the nation was losing its global prominence, as well as the Cold War. They wanted a president who would be tough, someone who wouldn’t back down from a confrontation.

They got what they wanted just a few days after Alsop’s survey appeared in the Post when President Kennedy ordered the U.S. Navy to block Russian ships from delivering missiles to Cuba. He put all branches of the military on highest alert, anticipating the Soviets would retaliate for the blockade. The world never came so close to nuclear war as it did between October 14 and October 28, 1962. Kennedy remained firm but approachable, and ultimately maneuvered the Russians into withdrawing their missiles.

Voters liked Kennedy’s tactics against the communists, even when they weren’t successful. After the Bay of Pigs fiasco—an outright disaster—his approval ratings rose from 78% to 83%. And in the aftermath of the missile crisis, his approval ratings rose from 62% to 74%.

This sense of America regaining the initiative in the Cold War may explain why so many Post articles and editorials were generous with praise for the president. It might explain why Joseph Alsop believed Kennedy had ushered in, “a time of renovation and renewal, when our country found a new and better course after long years of search… He had a vision of this nation’s greatness, which he somehow conveyed to the rest of us.”

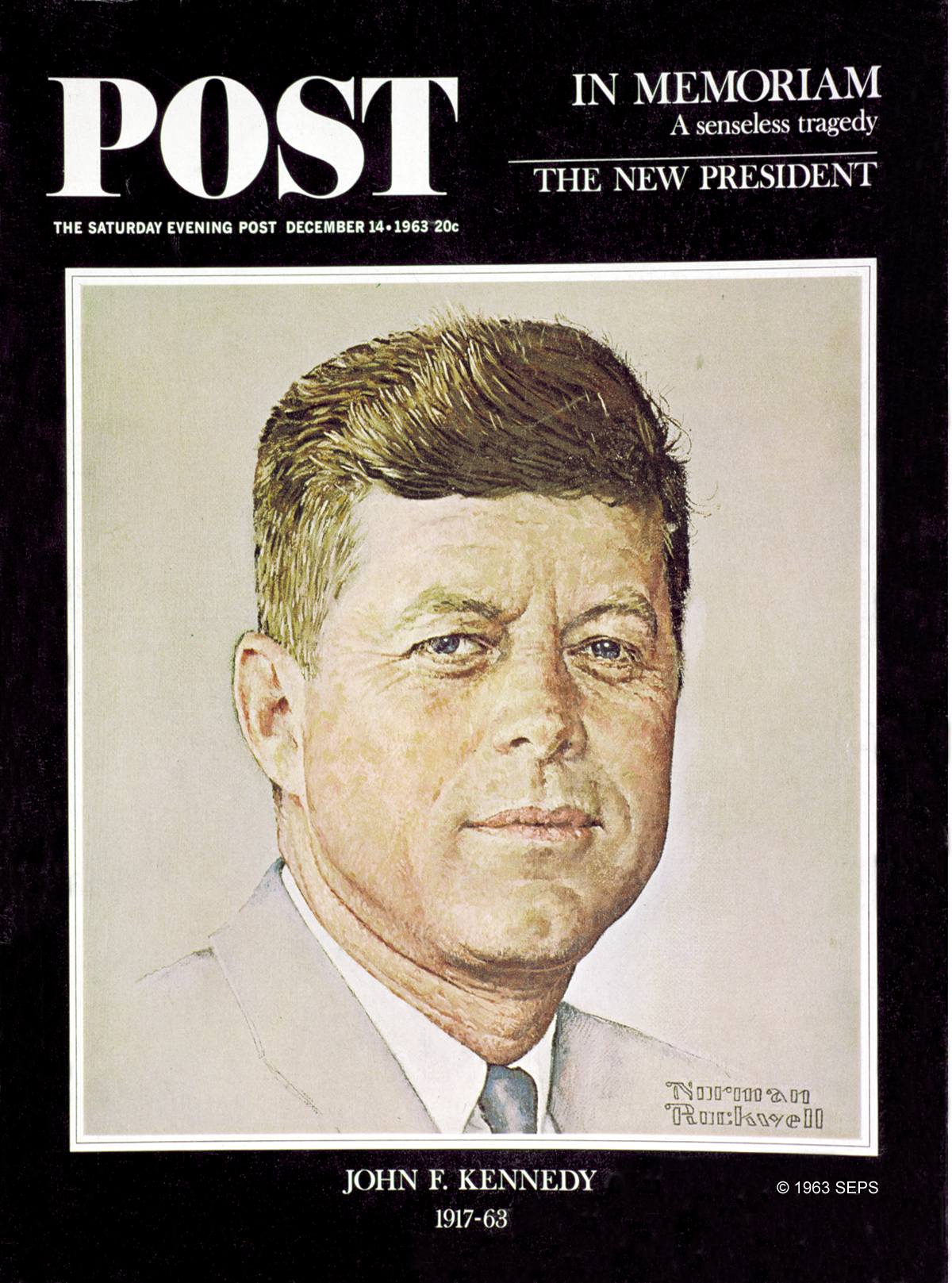

The Post Reports: Reconstructing Kennedy

Fifty years have passed since the assassination of John F. Kennedy, but the memory of that day has barely dimmed for most baby boomers. In conjunction with the Post’s reprinting of the Kennedy memorial issue published December 14, 1963, we present the following series of articles illustrating John F. Kennedy as he was seen in his time, before a half century of re-evaluation, criticism, and second-guessing.

These articles touch on key points of his time in office: his victories and blunders over Cuba, his Cold War strategy, and his late but crucial action for Civil Rights, and includes Post original material by Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist Ralph McGill, ex-president Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Breslin, Kennedy aide Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., and others.

The Unanswerable Question

Even before the Warren Commission met for the first time, the majority of Americans no longer believed a lone shooter was responsible for President Kennedy’s murder. Read more »

Why Kennedy Still Matters

The 35th president completed only three years of his term and left behind a pile of unfinished projects and unraveling plans. Yet Americans consistently rank him among our greatest presidents. Archivist Jeff Nilsson explains why we still love JFK. Read more »

Falling for Jackie Kennedy

Many Americans only got their first look at Jackie during the inaugural ceremonies, but her fashion sense and unflappable poise soon made her one of the country’s most admired first ladies. Read more »

How the Early 1960s Looked to Americans

The 1960s began with the election of a young, optimistic president who spoke of new opportunities. “Change is the law of life,” John F. Kennedy said, and in his inaugural address, he talked about “a new generation,” “a new alliance for progress,” “a new endeavor,” and “a new world of law.” Read more »

A Surprisingly Popular Presidency

Despite political opposition–and a few arguable failures in policy and tactic–John F. Kennedy remained a popular, well-regarded president throughout his short term in office. Archivist Jeff Nilsson explains why. Read more »

Rethinking Kennedy’s Camelot

In the years following President Kennedy’s death, many people often spoke of his presidency as an idyllic time, dubbing those pre-assassination days as “Camelot,” a noble, idyllic but ultimately doomed kingdom. In truth, America was already in the midst of troubling times that little resembled the idyllic innocence of Camelot. Read more »

Kennedy on the Campaign Trail

Doubts about then-Senator Kennedy’s religious affiliation, family ties, and youth made the viability of his campaign questionable. Yet when Post reporter Beverly Smith followed Kennedy on the campaign trail, she said it was “the most exciting presidential contest within [her] fairly extensive experience.” Read more »

A Very Eligible Politician

The first time the Post took notice of John F. Kennedy, he was still a very junior senator from Massachusetts. It was unusual for the magazine to run a feature article on a senator, particularly one as young and inexperienced as Kennedy. Read more »

JFK: The Most Eligible and Least Justifiable Bachelor

Long before his presidency, the Post was covering the political career of John F. Kennedy. In this 1953 article, the magazine introduced him to a national audience as “The Senate’s Gay Young Bachelor.” The following quotes show early stirrings of what would be come an infatuation with the young senator and his family. Sample some of these quotes and then check out the story in its entirety.

Kennedy [appears] to be a walking fountain of youth,” wrote Paul F. Healy. “He is six feet tall, with a lean, straight, hard physique, and the innocently respectful face of an altar boy at High Mass. Senators less generously endowed were especially taken with his trade-mark —a bumper crop of lightly combed brown hair that shoots over his right eyebrow and always makes him look as though he had just stepped out of the shower.Six years ago, when he started his first of three terms in the House of Representatives, Kennedy looked so young that he was mistaken by several other congressmen for a House page.

Kennedy wears an air of imperturbable informality; he often seems to be at once preoccupied, disorganized and utterly casual—alarmingly so, for example, when he solemnly addressed the House with his shirttail out and clearly visible from the galleries.

Many women have hopefully concluded that Kennedy needs looking after. In their opinion, he is, as a young millionaire senator, just about the most eligible bachelor in the United States—and the least justifiable one. Kennedy lives up to that role only occasionally, when he drives his long convertible, hatless and with the car’s top down, in Washington, or accidentally gets photographed with a glamour girl in a night club,” Healy wrote, but added that he was “basically a mature and responsible fellow.

At the time the story appeared, Kennedy’s bachelor days were already over. He and Jacqueline Bouvier decided to postpone announcing their engagement, which might have caused the Post to pull the “Bachelor” article. They announced their engagement 12 days later and were married on this day 60 years ago.

The article is also interesting for its description of the way Kennedy’s family helped him get elected.

Kennedy was reinforced by a task force from his large and fabulous family. His comely mother and three attractive, long-legged sisters took the stump, while his younger brother, Robert, acted as campaign manager.

There was nothing haphazard about the way the Kennedy women pitched in to help brother Jack. First they pounded the pavements to help collect a record total of 262,324 signatures on his nominating petition—though only 2500 were required by law.

Read the full story, “The Senate’s Gay Young Bachelor,” here.

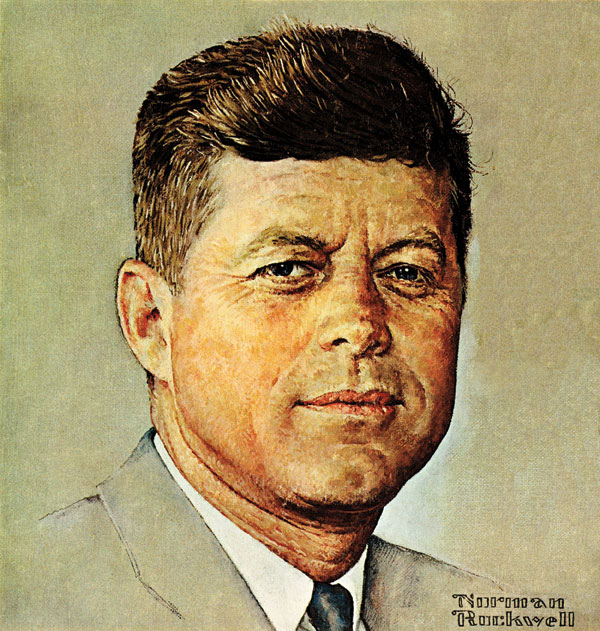

John F. Kennedy, In Memoriam

As an entire country lay in mourning in 1963, the Post released a special issue paying tribute to the fallen president just weeks after his death. The portrait of this great man by Norman Rockwell graced the cover. Selected excerpts below.

“A Profile in Family Courage”

By Bill Davidson

At 1:44 p.m. a maid came over to the table and said to the attorney general [Robert Kennedy], “Mr. J. Edgar Hoover is on the White House phone.” He had a conversation of about 15 seconds. There was a look of shock and horror on his face. [Ethel] Kennedy saw that, and rushed to where the attorney general had just put down the phone. He couldn’t speak for another 15 seconds. Then he almost forced out the words, “Jack’s been shot. It may be fatal.”

According to friends, [Jacqueline] Kennedy never once broke down during the dreadful night at Bethesda Naval Hospital or when she returned to the White House. A friend who spent a few moments with her on the morning of November 23 says, “She was composed, though you had the feeling she was barely holding on. But she revealed this only among people she held close. In public, she seemed completely composed. She is the kind of woman whose grief is private.”

But [Jacqueline] Kennedy also did other remarkable, less-publicized things in the first day of her grief. She offered Mrs. Johnson all her help for their move into the White House. Then she called in her brother-in-law, Attorney General Kennedy, and asked him to phone the wife of Dallas detective J.D. Tippitt, who had been killed by Lee Harvey Oswald, the principal suspect in the assassination of her husband. “What that poor woman must be going through,” said [Jacqueline] Kennedy.

“Hate Knows No Direction”

By Ralph Emerson McGill

His staff, the Secret Service and the FBI knew about the danger in Texas—as they knew of it in other states. But when the president appeared, the reception was so warm and generous, and the crowds so huge and friendly, that some of the vigilance was relaxed. The car’s bulletproof glass cover—which perhaps would have deflected the shots—was removed. And so, a trust born of warmth and generosity and friendliness exposed the young president to the deadly assault of a psychopathic hater.

The more shrewd among the peddlers of hate against their country have been careful to avoid open and direct incitement of violence. But their words and other abuse directed at the president and

the government have inspired many whose disturbed minds tend easily toward recklessness and criminal action.

We must now understand that hate, if unchecked by morality, decency, and the determination of civilized men and women, may so weaken us that we will be vulnerable to our enemies.

“A Eulogy: John Fitzgerald Kennedy”

By Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

The bright promise of his administration, as of his life, was cut short in Dallas. When Abraham Lincoln died, when Franklin Roosevelt died, these were profound national tragedies; but death came for Lincoln and Roosevelt in the last act, at the end of their careers, when the victory for which they had fought so hard was at last within the nation’s grasp. John Kennedy’s death has greater pathos, because he had barely begun—because he had so much to do, so much to give to his family, his nation, his world. His was a life of incalculable and now of unfulfilled possibility.

Still, if he had not done all that he would have hoped to do, finished all that he had so well begun, he had given the nation a new sense of itself—a new spirit, a new style, a new conception of its role and destiny.

“When The Highest Office Changes Hands”

By Dwight D. Eisenhower

Seen in longer perspective, the facts are that four of 36 presidents have been assassinated, and a president in office and a president-elect have been targets of assassination attempts. These acts all had one thing in common: They were the work of crackpots, of people with delusions arising from imagined wrongs or festering hatreds. In a population as large as ours there is bound to be a certain number of such warped people, but their existence does not indicate that the people of the United States have become lawless.

View a gallery of archival Kennedy images.

Looking Back at JFK

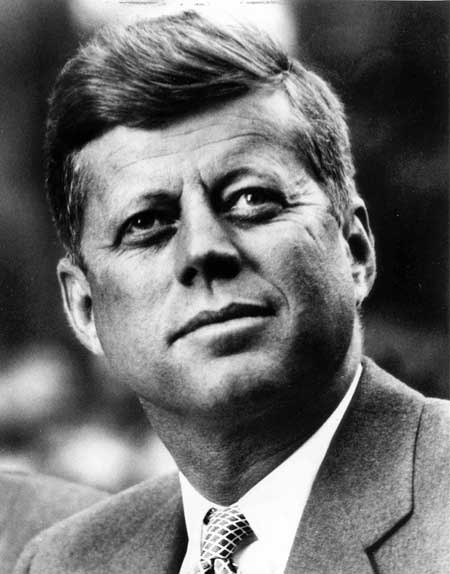

There are no doubts that John F. Kennedy’s looks were a considerable asset in his political career.

He looked young, which he was: elected to Congress at age 30, he was a senator by age 36, and president at 43.

He looked healthy, which he wasn’t: while president, he depended on numerous medicines to manage his back problems and Addison’s disease.

And he looked confident, which he was. Confidence had been in short supply in the 1950s, when Russia had gained the atomic bomb, taken the lead in the space race, and seemed ready to wage an unrelenting Cold War. Then, as the new decade was beginning, Senator John Kennedy arrived on the national scene, talking of America’s greatness and its role as a moral world leader.

In portraits as well as informal photographs, Kennedy always seemed to convey a unique, patrician energy and an effortless mastery of any situation. His appeal was only compounded by the poise and charming ways of his wife, Jacqueline, another political asset. They made being the president and first lady look easy. They never appeared flustered or annoyed, but gave the impression that everything was turning out the way they expected. Which was why Kennedy’s death was so disheartening. It seemed such a pointless, sordid end for someone who, to many Americans, embodied grace and idealism.

Despite the long shadow he cast in American culture, Kennedy was in the spotlight only a very brief time. These Post photos of JFK , from his campaign for the presidency to his death, cover only three short years. Because we never saw him grow old and exhausted, he will remain as we see him in these photos, an icon of the 1960s, a decade of hope and youth.

Read our new series examining the life and times of John F. Kennedy here:

The Post Reports: Reconstructing Kennedy

For a look at some of the original tributes to Kennedy, taken from the Post’s commemorative issue, click here:

Looking Back at JFK