A Brief History of the Minimum Wage

Recently, CBS News observed that it’s been 11 years since the last federal minimum wage increase, while in the same time period, the cost of living has risen 20 percent, squeezing low-wage workers who are already struggling during the pandemic. We took a look at the history of the minimum wage, controversies surrounding it, and the chances that Washington will raise it anytime soon.

Over 120 bills were sitting President Franklin Roosevelt’s desk on June 25, 1938, waiting for his signature. Somewhere in that stack was a bill that would have a huge impact on American labor. Called the Fair Labor Standards Act, it would, at first, only apply to businesses engaged in interstate commerce, and affect only 20 percent of America’s work force. But it outlawed child labor, set a maximum of 44 hours for a work week, and it guaranteed a minimum wage.

A similar law had been struck down by the Supreme Court in 1935. But the Court reversed itself two years later, and a new bill was sent through Congress. It met opposition from small manufacturers who declared they couldn’t afford to pay their workers the 40¢ an hour wage the law would require. Roosevelt compromised, setting the minimum hourly wage at 25¢ for the first year.

By this time in his administration, Roosevelt was accustomed to the cries of outrage from his opponents. The night before he signed the bill, he told Americans in one of his fireside chats, “”Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day…tell you…that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry.”

The following year, the minimum wage was hiked a nickel, to 30¢ an hour. The next raise came in 1945, when inflation followed the increased money supply circulating in the wartime economy. The wage rose to 40¢ an hour.

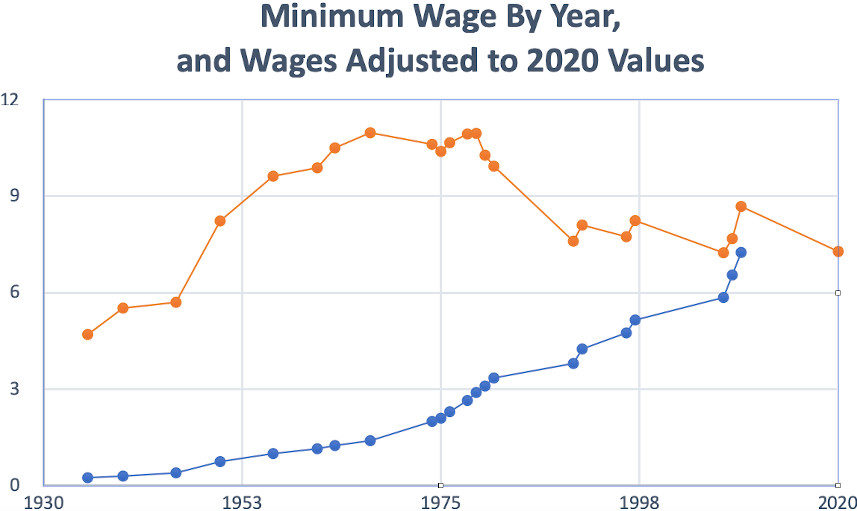

Over the years, the wage level has been lifted to reflect inflation and the rising cost of living. But successive congresses had differing ideas about what a minimum wage should do. Inaction led to the minimum wage often failing to keep pace with inflation, as shown below.

The lower line shows the actual hourly wage over the years. The upper line shown the value of that wage in 2020 dollars. Thus, the purchasing power of the 25¢ earned in an hour’s work in 1938 would be worth $4.70 today.

The highest minimum wage, when you adjust for inflation, was set in 1979, when it reached a value equivalent to $10.95 an hour today. Though increased several times, its relative value has gradually declined in the subsequent 41 years.

Today, a worker earning the federal minimum wage receives $7.28 an hour, before taxes. That wage was established back in 2009, and has set a record for the longest time without a raise. In the 11 years since then, the wage has lost 17 percent of its purchasing power.

Don’t confuse “minimum wage” with a “living wage” — the amount necessary to cover basic living expenses. Professor Amy Glasmeier of MIT has calculated a living wage based on estimated basic costs of food, child care, health care, housing, transportation, and other necessities, and compares it to the local minimum wage and poverty wage.

Poverty wage is lower than the minimum wage. A single person earning less than $12,760 is considered living in poverty. For a family of four, the figure is $26,200.

The poverty line was first calculated in 1955 by determining food expenses took up a third of a family’s budget after taxes. Therefore, the Agriculture Department multiplied food costs by three. The same calculation is used today, though the cost of food is continually adjusted in accordance with the Consumer Price Index.

The poverty wage determination is based on basic living. It doesn’t factor in varying housing or transportation costs. It doesn’t allow for leisure, entertainment, or food outside the Agriculture Department’s regimen of inexpensive meals. It means strict subsistence and no opportunity to save money.

For the average family of two adults and two children in the United States, the living wage is $16.54 per hour, or $68,808 a year. In contrast, the average minimum wage worker earns $15,080 a year.

If you hope to earn the living wage for a family of four, you would need to work almost four full-time jobs. At minimum wage, a single mother of two children would need to work nearly 24 hours a day for six days a week.

According to federal guidelines, two people with a total annual income below $16,910 are legally poor. The New York Times calculated that at least one person would need to earn a minimum of $8.12 an hour to escape the impoverished designation.

Since Washington can’t agree to raise the minimum, many states have stepped in to establish their own. As of 2018, 29 states, including Washington, D.C., have established minimum wages higher than the federal level. For example, Oregon, Washington, and Florida, which adjust their minimum wages to reflect rises in the consumer price index, pay workers between $9.00 and $11.00 an hour.

In addition, some cities have raised their minimum wage even higher. In Seattle, it will be $15.45 per hour next year. Not long ago, San Francisco raised its minimum to $15 per hour, which boosted the salaries of nearly a fourth of the city’s workforce.

There have been repeated efforts to raise the federal minimum wage. Proponents have argued that the current rate does little to help workers. Opponents claim that raising wages would lead to an increase in consumer prices and lay-offs of some workers to pay the higher wages of others. Economists have reported research that both supports and contradicts the various claims.

In 2019, when the House of Representatives passed a bill to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, the Congressional Budget Office predicted the law would increase the wages of 17 million workers, but put another 1.3 million out of work. The Center for Economic and Policy Research, on the other hand, found little or no change in employment resulting from modest increases in the wage.

One benefit to raising the minimum wage could be increased spending among lower income workers, leading to a higher demand for goods. (This was Henry Ford’s thinking when he raised his minimum wage to a record-breaking $5 a day. “The owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same,” he wrote, “and unless an industry can… keep wages high and prices low, it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers.”)

Another unexpected effect of raising the minimum wage could be the reduction in government spending. According to a UC Berkeley study, over half of fast-food workers rely on public assistance checks to get by. Just raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would eliminate $7.6 Billion in income-support programs.

The prospects for increasing the minimum wage don’t appear good. In the current economic climate, with 10 percent unemployment, the supply of labor exceeds the demand. Workers have little leverage over employers. Businesses, particularly those operating on margins made razor-thin by the recession, will have small motive to increase pay.

A further obstacle is indicated by a recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which found employers often respond to minimum-wage hikes by bringing automation in to take the place of human workers.

The good news, though, is that fewer and fewer Americans are limited to living on that income. In 1980, 17 percent of workers were receiving minimum wage. In 2018, that percentage had dropped to just only 2 percent.

Featured image: Hyejin Kang / Shutterstock

Considering History: The Fundamental Radicalism of the American Labor Movement

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Last week, nearly 50,000 members of the United Auto Workers union went on strike at General Motors factories across the country, one of the largest national strikes in decades and part of a larger trend toward significant labor actions. And in a few weeks, Netflix will premiere director Martin Scorsese’s much-awaited new film The Irishman, which stars legendary actors Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in a historical drama depicting controversial labor leader Jimmy Hoffa and his ties to organized crime in mid-20th century America. These events are bringing renewed attention to different sides of the American labor movement.

While Hoffa was only one figure, and his historical legacy has perhaps been overstated due to his still-mysterious disappearance, Scorsese’s film reminds us of a central element to the 20th century labor movement: its status as a racket. It’s impossible to tell the story of American labor over the last 100 years without engaging that side of the story, not just through overt aspects like the relationship to and role of organized crime but also through labor leaders and organizations that have themselves operated much like mob bosses.

Yet like Hoffa’s larger-than-life legacy, those aspects of the labor movement can be given too prominent a place in our collective memories — and in so doing, we risk forgetting the truly radical origins of the labor movement in America, legacies that importantly contextualize today’s national strikes.

The 1877 railroad strikes, which are generally seen as the first such national such labor actions, exemplify those radical origins. Strikes had been part of American society since its first European settlements, with Polish craftsmen in the Jamestown colony striking for fair treatment and civic rights in 1619. As early as 1648, Boston coopers and shoemakers both formed workers’ guilds to advocate for workplace standards and practices. But for the next two centuries, both labor organizations and labor actions would remain largely at the local level, achieving advances in their particular communities but not uniting larger cohorts of American workers in service of shared, societal goals.

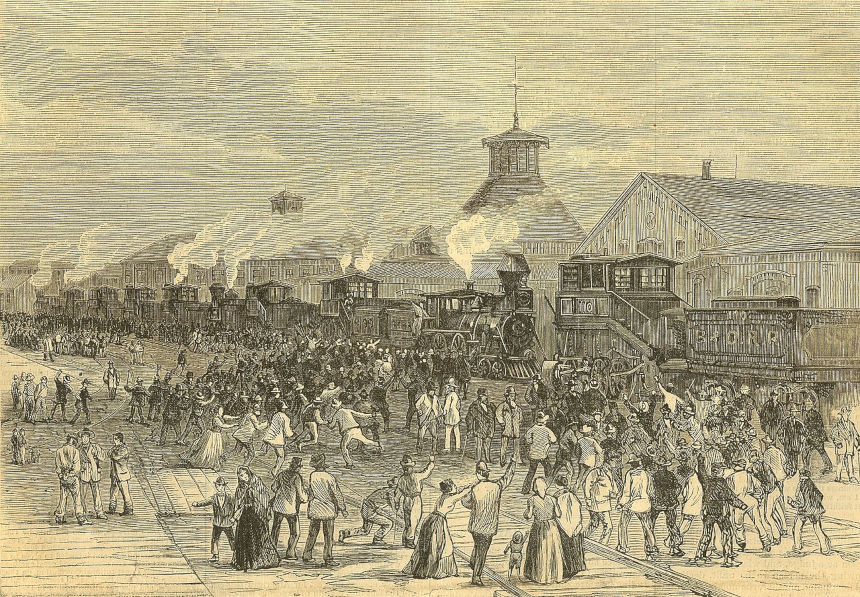

The 1877 strikes would bring labor organizing and activism to the national stage. They began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, where the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad had cut its workers’ wages for the third time in a year. In response, striking workers stopped all train service in the city. Governor Henry Mathews sent in the state militia to end the strike, but the soldiers would not fire on the strikers and the labor action continued. It soon spread to other mid-Atlantic states, with the first follow-up strikes in the Maryland cities of Cumberland and Baltimore, as well as a more violent clashes between the militia and strikers in that latter city. By the end of July strikes and violence had reached Albany, Pittsburgh, Scranton, Chicago, and East St. Louis, among other cities.

The combination of widespread, sustained labor actions and extreme, violent responses led these 1877 events to be known collectively as the Great Upheaval, and both elements reflected the moment’s profound radicalism. The strikers wanted to achieve their immediate goals (such as wage guarantees and increases), but also advocate for broader, systemic changes that would affect workers across the nation and in every industry. That is, even while they fought for their lives and rights, the 1877 strikers, organizers, and labor leaders also advocated for issues like child labor laws, health and safety regulations, and the 8-hour workday.

The consistent use of troops and violence to respond to the strikes likewise reflects the moment’s truly revolutionary nature. Like Governor Mathews in West Virginia, the authorities in each affected city and state called out not just police but also state and volunteer militias (as well as private armies like the infamous Pinkerton detectives); and unlike in Martinsburg, in far too many cases those units did not hesitate to use lethal force. When those local and state forces were unable to stop the strikes, President Rutherford B. Hayes went one step further, sending federal soldiers to each city in order to suppress both the violence and (especially) the labor actions themselves. These nationwide clashes between American soldiers and rebels could be accurately described as a brief but brutal period of revolution or civil war that reflected the moment’s profoundly radical nature and effects on American society.

Beyond those violent repercussions, the effects of the 1877 general strike were both immediate and long-lasting. On May 1, 1880, the B&O Railroad company established the Baltimore and Ohio Employees’ Relief Association, a groundbreaking example of worker insurance and protection; four years later, the company offered one of the first corporate pension plans in American history. On a broader scale, the national labor movement grew exponentially in the years following the strikes: the Knights of Labor, the first truly national union, grew from a few thousand members in the 1870s to 28,000 in 1880 and roughly 700,000 by 1886 (with many members also separating to form the American Federation of Labor); and the 1880s as a whole would witness more than 10,000 strikes and labor actions, as this form of radical activism became a commonplace part of American society.

Yet to my mind, despite such prominent effects neither general strikes nor violent clashes reflect the labor movement’s most radical elements. Instead, I would emphasize the ways that movement represented a diverse coalition of American workers. Too often, the movement relied upon hierarchies or discriminations, such as the late 19th century American Federation of Labor (AFL)’s use of the category of “skilled labor” to consistently exclude immigrants and African Americans.

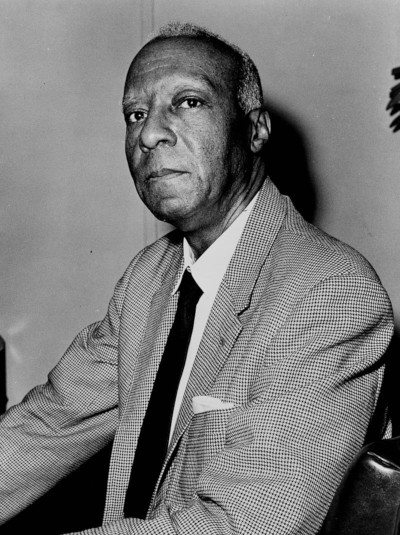

Instead, labor leaders of color helped actively resist discrimination and model an inclusive labor movement. A vital case in point is the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive an AFL charter. African-American Pullman porters had comprised the vast majority of that workforce since the railroad company’s late 19th century origins, and Pullman remained one of the nation’s largest employers of African Americans into the 1920s. Porters had tried unsuccessfully to organize for years, but in August 1925 a group of more than 500 met in Harlem, formed the BSCP under the slogan “Fight or Be Slaves,” and chose New York labor organizer A. Philip Randolph (previously co-founder and president of the short-lived African-American union the National Brotherhood of Workers in America) as their first president.

Powerful figures like Randolph and his BSCP co-founder (and first vice president) Milton Price Webster, a Chicago political leader in the era’s “black Republican machine” as well as a lifelong labor activist, represent a key contrast to more corrupt labor leaders like Jimmy Hoffa. Randolph and Webster certainly ruled the BSCP throughout its early years, quickly turning it into a national powerhouse that by 1929 received affiliated status from the AFL. But they did so in order to advocate for the under-represented workers and gain them a voice. Their efforts produced inspiring legacies: in labor activism, as illustrated by Pullman’s ground-breaking August 1937 contract with the BSCP; and in civil rights, as Randolph in particular would become a leading voice in the nascent Civil Rights Movement, as exemplified by his June 1942 Madison Square Garden address to an audience of nearly 20,000 African Americans, a speech that launched the era’s March on Washington Movement.

From the 1877 general strikes to that 1940s activism, and up through today’s UAW actions, time and again the labor movement has represented a radical force in American society, politics, and culture. While we can’t ignore the darker sides to the movement, whether its discrimination or its links to organized crime, neither can we afford to minimize that fundamentally radical legacy. Not if we want to understand our histories, and not if we want to move forward into the kind of fair and equal society that the labor movement can help us create.

Featured image: The Sixth Maryland Regiment confronts striking workers in Baltimore (photo by D. Bendann, Harper’s Weekly, August 11, 1877, Library of Congress)

A Week Without Seattle

Seattle, long before it became the city of Starbucks and Amazon, was a bastion of union membership. Workers of all stripes were organized into labor groups that comprised a heavy presence in everyday life, and they made history. But you might have to search further than a textbook — or even a city library — to find it.

On the evening of February 6, 25 members of the Seattle Labor Chorus will surround an audience in the atrium of the Museum of History and Industry, singing songs like “Commonwealth of Toil” and “Ship Gonna Sail” and reading dialogue from historic Seattleites like Anna Louise Strong and Ole Hanson. The performance, called Labor Will Feed the People, is a celebration of the legacy of the Seattle General Strike, a labor action that virtually shut down, and seized control of, the city 100 years ago.

When Robert Friedheim wrote, in 1964, about the Seattle General Strike of 1919, he deemed it ultimately harmful to the labor movement of the time since the participating unions’ goals were not accomplished and they appeared to lose a nationwide propaganda war that sparked a Red Scare. If the big strike was such a “public relations disaster for labor,” you wouldn’t know it by the year-long Solidarity Centennial the city has planned to celebrate its impact.

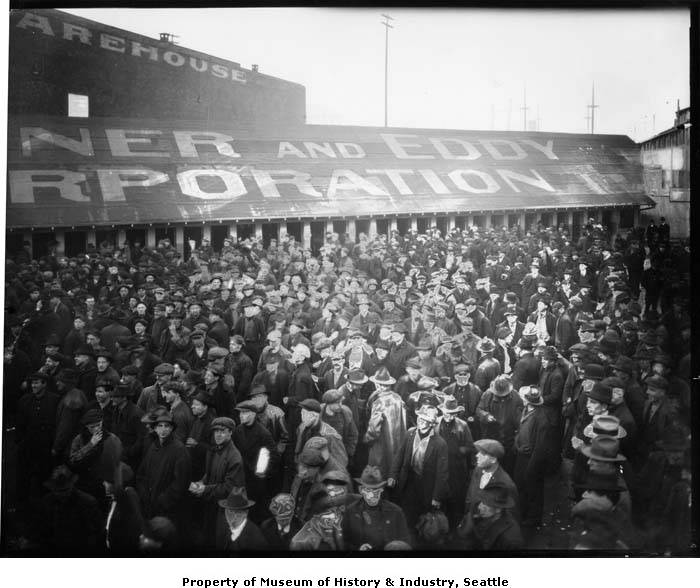

The general strike began 100 years ago today, when around 65,000 workers walked off their jobs. Shipyard workers had already been striking for a few weeks due to their stagnant wages after the war, and laborers in myriad other industries voted to join them. Union membership in Seattle was robust and organized: hotel maids, waitresses, house painters, street car conductors, and many other kinds of workers stood in solidarity with the shipyard workers as members of the Central Labor Council.

The political leanings of strikers ranged from the revolutionary “Wobblies” (Industrial Workers of the World) to more conservative unions, but journalist Anna Louise Strong’s statement in the Union Record on February 4 was widely interpreted as a socialist declaration: “We are undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by LABOR in this country, a move which will lead — NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!” Strong claimed it was not the mere withdrawal of work that would make the strike successful, but rather the ability of the union to maintain the feeding, cleaning, and order of the city: “THIS will move them, for this looks too much like the taking over of POWER by the workers.”

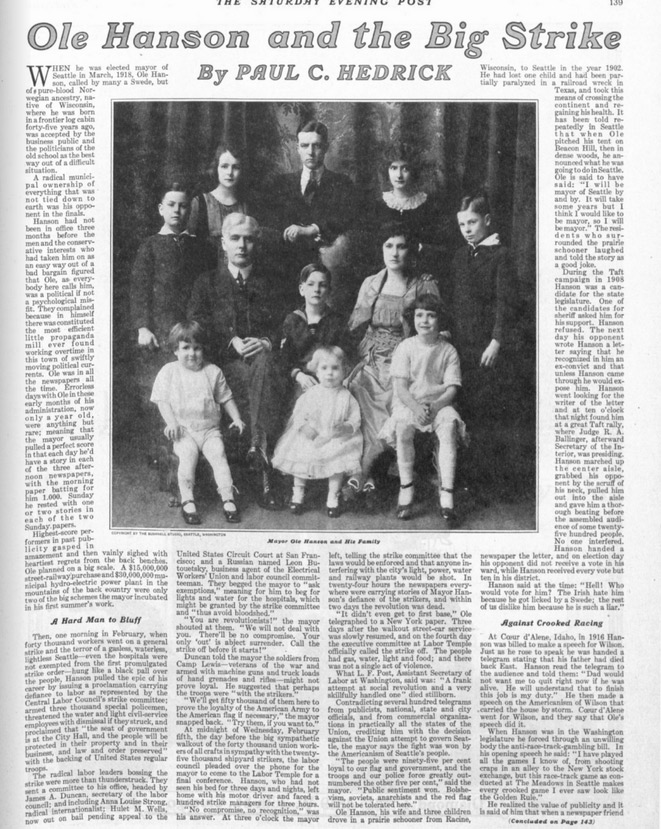

Ole Hanson, the city’s mayor, was initially receptive to the unions, but he quickly took to newspapers near and far to stoke fears of the strikers as anti-American Bolsheviks. He brought in thousands of “special deputies” to the city, raising expectations for violence. Hanson proclaimed on the second day that if the strike didn’t break by February 8 he would declare martial law, which he didn’t actually have the power to do.

“One of the miscalculations by the Central Labor Council was not realizing the fierce backlash that would come from Mayor Hanson and the city’s major newspapers,” says James Gregory, a Professor of History at University of Washington. “The labor movement in Seattle and around the country had many different dimensions. Some of the excitement around the strike came from a left-wing segment that was energized by revolutionary insurgencies happening around the world,” he says, “but most of the strikers were just compelled by an anticipation that organized labor could advance as a responsible participant in decision-making nationwide after being denied that recognition during World War I. There was also a worry that large employers were preparing an ‘open shop’ campaign to try to break unions.”

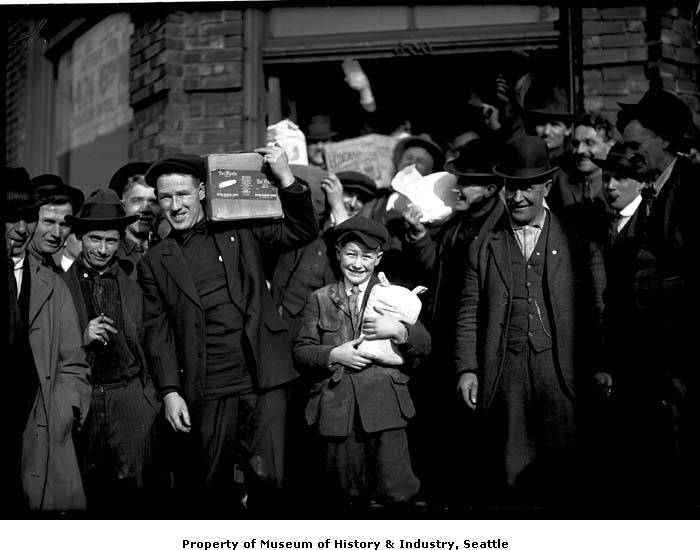

The Seattle Star printed warnings to strikers to “Stop before it’s too late,” calling the strike a “drastic, disaster-breeding move” and “a test of Americanism.” The general strike came to pass, however, and the CLC organized for the most necessary city functions. Milk stations and kitchens were announced to feed union and non-union families, and drug stores resumed the filling of prescriptions. The CLC organized a welfare committee to provide crucial health and sanitation services and even a law and order committee that dispatched veterans of the war to patrol the streets unarmed.

“Nothing moved but the tide,” said longshoreman striker Earl George in reference to the calm of Seattle during the strike. Contrary to the fearful warnings of Mayor Hanson and newspapers around the country, violence did not break out in the city. “It was completely peaceful,” Gregory says. “For the first time a major strike had been conducted without violence or arrests.”

As the days passed, however, the fervor of strikers diminished as they failed to see a desirable outcome. Ole Hanson was regarded nationally as a hero of “Americanism” for standing up to the union’s demands. The general strike ended on February 11, and Hanson — ever the opportunist — resigned as mayor later that year to make a fortune on a national speaking tour. This magazine even printed a glowing profile of Hanson in 1919, praising his hard stance against “radical internationalists” and “syndicalists.”

There were crackdowns on unions and new “open shop” policies throughout the city, and the shipyard workers were no better off. But, according to Professor Gregory, this shouldn’t lead anyone to believe that the strike was an abject failure. In the recently published edition of Robert Friedheim’s 1964 book, The Seattle General Strike, Gregory has written a new introduction to account for a wider assessment of the impact and significance of the action that he says put Seattle on the map. “If you back away from a kind of ‘football score’ assessment, the general strike was very instrumental in encouraging one of the great strike waves in American history,” Gregory says. “The willingness to think as a broad community of labor is what is refreshing and fascinating about this event. We don’t see it much in the culture of individualism in modern life.”

That sense of class community is exactly what playwright Edward Mast has attempted to capture in his play Labor Will Feed the People. He has compiled historical documents and statements from an array of Seattleites to show the diversity of experiences during the strike and to bring to life the spirit of solidarity from 1919.

Mast believes the story of the strike will resonate with a devoted Seattle audience. “In a time of rising inequality that has so great an impact on us, it’s important to look back at a time when working people had a stronger voice,” Mast says. “That there were active labor communities that could make decisions on their own and also contribute to a larger division in this city is something people might miss: when we were organized into units that could collectively make decisions in the interests of justice and equality for the community.”

The performance, and other events in the centennial celebration, will also focus on voices that were left out of the strike, like the African-American, Chinese, and Japanese workers who were largely excluded from the Central Labor Council’s organizing.

Given the depth of the city’s labor history and wide spectrum of progressive politics, Mast is confident about the potential of the event to reach a lively, engaged audience of Seattleites and renew interest in a history that shouldn’t seem so niche. “One of the voices [in the performance] speaks about how wages were not going up as quickly as rent prices were,” he says. “So, as is often the case, there are direct parallels to our immediate experience.”

Considering History: Voices and Stories of the Mexican-American Experience

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the prior two posts in this series on Myths and Realities of the Mexican-American Border and Mexican Americans as Political Prop in the 20th and 21st Centuries, I’ve traced the Mexican-American border’s constructed and contested nature, the border patrol’s origins and initial role in the Chinese Exclusion era, and the use of Mexican Americans as a political prop throughout the 20th century. These histories form a vital backdrop for any conversations about the border and immigration, and as a result need to be more fully understood in our heated contemporary moment.

Yet one element is largely missing from those posts: the voices and stories of Mexican Americans themselves. In each historical period, we find compelling stories that certainly highlight the effects of our most exclusionary national policies but that also exemplify how Mexican Americans have fought for their own and their community’s rights within an evolving America.

María Amparo Ruiz de Burton Depicts the Mexican-American Experience

The first Mexican-American author to publish fiction in English, María Amparo Ruiz de Burton, experienced first-hand and wrote about the late 19th century aftermath of the Mexican-American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The daughter and granddaughter of Mexican generals and political leaders, after the Treaty a teenage Ruiz moved north to Alta California with her family. She met and married an American military officer, and they began operating a ranch just outside of California. But he was injured during the Civil War and died shortly thereafter, and when Ruiz de Burton returned to California with her two children she found that Anglo squatters had occupied the ranch (a far too common experience for Mexican-American landowners in the era).

For the remainder of her life Ruiz de Burton fought legal and political battles to regain and secure her ranch and land claims. At the same time, she published a number of literary works, including two compelling novels: Who Would Have Thought It? (1872), which uses the story of an adopted mixed-race girl to satirize Anglo-American ideals and prejudices; and The Squatter and the Don (1885), which highlights the experiences of both Anglo arrivals and Mexican landowners in post-Treaty California. While these novels do not shy away from the harshest realities of late 19th century Mexican American life, Ruiz de Burton also portrays an American future that includes (and in Squatter romantically unites) all these cultures and communities.

Stories from the Mexican Repatriation Program

The Mexican Repatriation program of the 1930s represented one of the first national policies that sought instead to exclude Mexican Americans from that shared future. Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez’s Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (1995) features the stories of many of the millions of Mexican Americans (a majority of them birthright citizens) affected by this exclusionary policy. In one telling moment in the book, Southern California radio host José David Orozco and his guest Dr. José Díaz share stories of married couples and families separated by the region’s deportation sweeps. And the policy’s effects were felt nationwide, as illustrated by a groundbreaking 1973 study of the near-complete destruction of the Mexican-American community in Gary, Indiana (where many had been employed by U.S. Steel).

The Successes of the League of United Latin American Citizens

Many Mexican Americans fought back against the era’s discriminations. Founded in February 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was modeled in part on the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP). Two founding members, Pedro and María Hernández, were particularly instrumental in developing LULAC’s multilayered social and political agenda: María, an elementary school teacher and mother of ten, focused on educational outreach and support for expectant and new mothers; Pedro, a political and legal activist, organized a successful lawsuit challenging the Texas legislature’s longstanding policy of excluding Mexican Americans from juries. Over the next decades LULAC would extend those efforts: creating community education and preschool programs (such as the popular Little School of the 400 program); conducting voter registration campaigns and opposing efforts to disenfranchise Hispanic voters; suing school districts that denied Mexican-American students equal access and opportunities; and advocating for both basic rights and full citizenship for Mexican and Hispanic Americans. Two of their successful educational lawsuits, Mendez v. Westminster (1945) and Minerva Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District (1948), helped create the precedents that would lead to the Supreme Court’s turning point anti-segregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Many Mexican Americans fought back against the era’s discriminations. Founded in February 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was modeled in part on the National Association for the Advanced of Colored People (NAACP). Two founding members, Pedro and María Hernández, were particularly instrumental in developing LULAC’s multilayered social and political agenda: María, an elementary school teacher and mother of ten, focused on educational outreach and support for expectant and new mothers; Pedro, a political and legal activist, organized a successful lawsuit challenging the Texas legislature’s longstanding policy of excluding Mexican Americans from juries. Over the next decades LULAC would extend those efforts: creating community education and preschool programs (such as the popular Little School of the 400 program); conducting voter registration campaigns and opposing efforts to disenfranchise Hispanic voters; suing school districts that denied Mexican-American students equal access and opportunities; and advocating for both basic rights and full citizenship for Mexican and Hispanic Americans. Two of their successful educational lawsuits, Mendez v. Westminster (1945) and Minerva Delgado v. Bastrop Independent School District (1948), helped create the precedents that would lead to the Supreme Court’s turning point anti-segregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

The Bracero Program Sparks Activism

The Bracero Program was series of agreements between the U.S. and Mexico that promised decent living conditions to Mexicans who came to the U.S. to fulfill a labor shortage in agriculture, starting in the 1940s. It brought new Mexican Americans to the U.S., and they added their voices to this evolving story. The National Museum of American History’s wonderful exhibition, Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942-1964, captured many bracero voices and experiences, documenting each stage of bracero life from the journey and the border to brutal conditions, labor activism, and multi-generational family legacies. One quote, from former bracero Guadalupe Mena Arizmendi, sums up both the program’s realities and its possibilities: “Es puro sufrimiento, le digo, allí sí se sufre y allí andamos, eso queríamos (I tell you, it is pure suffering, there you suffer and there we were, that is what we wanted).” Mexican-American author Tomás Rivera, himself the son of braceros, portrays the community’s experiences and legacies with grit and power in his novel And the Earth Did Not Devour Him (1971).

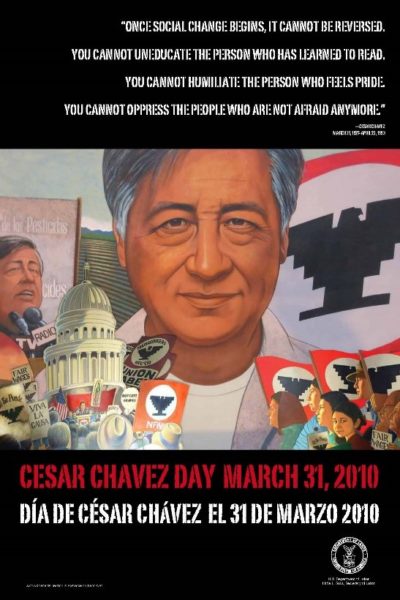

Out of the Bracero Program and era came as well the first moves toward national activism on behalf of migrant laborers. Dolores Huerta, the daughter of a migrant laborer father and a mother who ran a hotel and restaurant for migrant workers, founded the Agricultural Workers Association in 1960 when she was just 30 years old; two years later she joined forces with César Chávez, the son of two migrant laborers and then the Executive Director of the activist Community Service Organization, to co-found the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). A few years later, the NFWA joined striking Filipino-American laborers from the Agricultural Workers Organizing Community (AWOC) in the 1965 Delano (CA) grape strike, a hugely influential effort that would last nearly five years, lead to the founding of the United Farm Workers (UFW) when the two groups merged, and fundamentally reshape late 20th century American labor and politics.

Operation Wetback’s Legacy

These decades continued to witness anti-Mexican-American discrimination and exclusionary policies, most notably the mid-1950s federal deportation program known as Operation Wetback. Historian Mae Ngai’s award-winning Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (2004) features the stories of many of those affected by Operation Wetback. She highlights, for example, a July 1955 incident in which “some 88 braceros died of sunstroke as a result of a roundup that had taken place in 112-degree heat, and … more would have died had Red Cross not intervened.” Elsewhere she quotes a congressional investigation that referred to a ship transporting deportees to Mexico as the equivalent of “an eighteenth century slave ship” and a “penal hell ship.” LULAC’s newsletter depicted deportees arriving in Mexico as “broken men, with strength spent and exhausted by the senseless struggles of a life revolving around slavish, ill-paid labor, and the degradation of jail and prison cells.”

The Accomplishments of the National Council of La Raza

These evolving exclusionary policies required new activist organizations, and the 1960s saw the creation of a vital one: the National Council of La Raza. La Raza was also the name of a community newspaper edited by Eliezer Joaquin Risco Lozada, a prominent young activist in Fresno who would go on to open rural health clinics throughout the region, create the first La Raza Studies (later Chicano Studies) program at Fresno State University, and advocate for Latino-American rights throughout his inspiring life. In March 1968, inspired by Lozada and other activists, Southern California high school students led the East Los Angeles Walkouts, a stunning and successful mass action that garnered national attention and made clear that Mexican- and Latin-American communities were fully part of the era’s burgeoning civil rights movements.

Writers Chronicle Mexican-American Life

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the emergence of a number of Mexican-American creative writers who brought these histories, stories, and communities into their ground-breaking literary works. Novelist Rolando Hinojasa has created, across the 15 volumes to date in the Klail City Death Trip Series, a fictional border county and community modeled on the South Texas Rio Grande Valley in which he grew up. Scholar and activist Gloria Anzaldúa likewise grew up in the Rio Grande Valley, and turned that border setting into the basis for her multi-lingual multi-genre masterpiece Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987) among many other works. And Professor Norma Cantú, the foremost translator of and scholar on Anzaldúa’s works, has published her own memoirs as both a Mexican-American immigrant and a 21st century contributor to the continuing story of Mexican-American identity and community.

As part of his trip to the Rio Grande Valley and the border last week, President Trump visited Anzalduas Park, a county park along the river. Perhaps this historical moment can produce more than further border and immigration debates—perhaps it can lead us to more collective engagement with the story of Gloria Anzaldúa and other Mexican-American figures and communities. Their voices deserve a far more central role in our collective memories, our present conversations, and our shared future.

Note: This piece benefited greatly from the suggestions of Professors Laura Belmonte and John Buaas.

The National Crisis in Boston

November 15, 1919

It became that instantly. For more than a year events had been shaping toward a showdown between the radical elements of organized labor and the American public, and the moment the Boston police walked out they precipitated the fight. Not that they intended to do so or even dreamed of the effect. To the police it was a local dispute, with purposes limited to betterment of their condition. They were far from wishing to bring on a conflict with public opinion. Indeed they hoped and confidently expected that public opinion would side with them. But circumstances carried the clash between the policemen and Commissioner Curtis into every city and town and hamlet in the United States; a mob of hoodlums elevated a local issue to a national crisis.

What happened in Boston on the night of September 9 woke the country with a jolt. Had no serious disorders occurred, probably the people of America would have viewed the policemen’s strike as merely another manifestation of organized labor’s ever-widening activities and bothered their heads very little about it. But a lawless rabble looting in the heart of Boston jarred like a blow in the face. The scales of indifference fell from their eyes; abruptly they realized the peril hanging over the Republic.

Seldom have all classes reacted so unanimously in peacetimes. They rallied in a day for a finish fight. It was no longer Boston’s affair alone, but the nation’s. Boston happened to be the standard bearer, as she has so often been in the past, but back of her stood the American public. It was hard on that stout old defender of liberty, but Boston never hesitated.

“If the radical crowd in organized labor gets away with this,” she said in her chaste fashion, “they can get away with moider.” And she girded herself for the fray.

In the nature of things it had to be a fight without compromise — and the public won. Never was a victory more complete. With defeat absolutely certain from the outset, the American Federation of Labor declined to lock horns over any such issue. They refused to sanction a general sympathetic strike to support a walkout which had never been approved by the older leaders of organized labor, and when the Central Labor Union declared its stand, the policemen’s union was finished. Without the federation they were powerless, and the federation had been obliged to let them down.

The Labor Camp Divided

Many observers see in the ignominious failure of the Boston strike a bad black eye for organized labor, but I would not call it that. It’s a lovely black eye for the elements which have been striving to stampede the federation, and for that very reason may prove of distinct service to the cause of labor. Every honest man ought to rejoice over it. But never lose sight of the fact that the federation did not approve of the strike. Whatever outside encouragement stimulated hopes in the policemen which could not be realized, it certainly did not come from the head of the American Federation of Labor or his friends. And the policemen’s union charter expressly forbade a strike.

Then who encouraged it? For it is reasonable to suppose that the police would not have dared a walkout without some sort of understanding that they would be backed by labor. Their counsel did not. James H. Vahey and his associate not only advised their clients strongly against a strike but urged them to give up affiliation with the American Federation of Labor. In spite of that — in spite of the provision against a strike in their charter — they walked out. Who egged them on?

The ultimate effect of this police strike will probably be to strengthen the hands of President Gompers and the more temperate leaders, against whom the radicals in the federation have been waging war for years. In fact, there is more to several recent labor disturbances than the usual dispute between capital and unionism. A lively fight has been going on inside the federation itself. Elements which formerly were identified with I.W.W. thought and aims procured a foothold in the American Federation of Labor and immediately came into conflict with the established leaders. Every minute since then they have sought by hook or crook to wrest control of organized labor from Gompers and his associates.

I have heard gentlemen who had no worries more poignant than their golf scores and the income tax assail Samuel Gompers with the peculiar venom we reserve for those who hit our pockets. To that class he is a dangerous demagogue, a near-Bolshevist, a menace to American institutions and dividends. On the other hand you hear the radicals charge that Gompers is the tool of capital and belongs among the reactionaries. And there you are! Score this to Gompers’ credit — during the war, he proved himself 100 per cent American.

The radicals would now oust him from the headship of the federation. They have nearly got the Old Man’s scalp on several occasions, too. While he was absent in Europe, they contrived to gain support for several things to which Gompers was opposed, and their power has grown so greatly with the deep discontent and socialistic ideas engendered by the war that Gompers has been obliged to acquiesce in a number of activities he would not have countenanced a moment in the days when his word was law to the unions.

On occasions the radicals have practically run away with the federation, and Gompers has been forced to sanction strikes which no man of common sense and judgment could conceivably approve. Now, nobody ever disputed Gompers’ common sense; consequently, it seems safe to assume that the disastrous failure of these frenzied efforts and the resultant loss of prestige to those responsible have been borne with a certain equanimity by the older leaders. There is an ancient saw to the effect that if you give a calf enough rope, it will hang itself.

To everybody but a Bostonian, it seems peculiarly fitting that The Hub should have been the battleground, for whenever in American history the drums beat to arms in defense of a principle, Boston has led the van. Bostonians think pretty well of themselves, but I doubt whether they have even a glimmering of the deep veneration in which the bulk of American citizens hold their city. This is especially true of rural America. To them and to the Middle West and West, Boston stands as a shrine to which pilgrimages are made when the crops bring good prices or the school board raises salaries.

The Home of Forward Thinking

Provincial Americans entertain a certain awe of a New Yorker because of his airy ways and city manners, but deep down in their hearts they know that under his veneer, the New Yorker is just as big a rough-neck as they are. But toward the Bostonian they feel a real respect as the possessor of a superior culture and finer grain. That this notion belongs in the category of silly national illusions doesn’t alter the fact of its existence.

Of course, New York and other places which are always in a hurry have been known to laugh at Boston, and they make her the butt of their vaudeville jokes. Often I have seen the ribald press get off paragraphs like this: “Why not make a test case by taking an obsolete city, say Boston, and let everybody and everything in it strike to a finish, and abide by the result?” But Boston never pays such no-account trash any attention. She goes her way serenely, secure in the knowledge that she is The Hub of the universe and the last word in culture and good breeding.

To be sure, she takes her time. Sometimes—sometimes — she seems just a leetle bit slow. That was the impression I got on revisiting Boston after an absence of 10 years. The city didn’t appear to have changed at all. Everything looked the same — only smaller. I dropped into a restaurant which some of us used to patronize on pay nights; the same waiters, the same bill of fare, the same orchestra — and as heaven is my witness, the same clam chowder! Mike, the waiter, wanted to know where I’d been keeping myself the last few days. He had changed his collar, otherwise I could detect no difference in Boston.

Yes, Boston moves slowly and is inclined to hold herself aloof — perhaps her most pressing need is to learn the United States — but if you take the trouble to trace any important civic movement or social-uplift plan or humanitarian campaign to its source, you will invariably find it in The Hub. She has generally led in forward thinking, just as Massachusetts has led in progressive legislation.

This is due to the caliber of her citizenship. Nowhere in America can you find proportionately such great numbers of business and professional men with a high sense of public duty. First impressions of Boston may be unfavorable. The visitor is apt to dislike the New England coldness. He may grow impatient of their woeful ignorance of the world beyond Jamaica Plain and chafe at a viewpoint which strikes him as narrow and hopelessly provincial. The complacence of Bostonian satisfaction with itself may excite levity in the barbarian bosom of a guy from Chicago, and the seriousness with which they take their proud old families of 1776 and 1913 frequently causes outsiders to exclaim, “This darned place is a trance.” But let anyone remain a year and he will end up with a profound respect and affection for Boston, its institutions and citizenship.

So much for the setting of the drama. In this rock-ribbed stronghold of American ideals an issue was forced which involved the very principles on which the Republic was founded. One would have thought that Boston would be the last place on earth the radicals would pick for a test of strength. The police assuredly showed rotten judgment. Imagine anybody or any group of men hoping to scare that New England breed into acquiescence! As well try to hurry them!

To the United States, the policemen’s strike came like a bolt from a clear sky, but in reality there was nothing sudden about it. It had been looming as a possibility for a month, and the causes leading to the impasse are of long standing. Until I investigated the situation, my voice was joined to the chorus of unqualified denunciation which was directed against the police from coast to coast; they were damned from every quarter of America, branded as deserters, traitors, and fit bedfellows for Trotsky. The condemnation was justified, but some of the denunciation was grossly unfair.

Nothing can excuse or palliate the offense of walking out and leaving a city unprotected, but intention counts both in law and morals and the police stoutly contend they hadn’t an inkling of what the consequences would be. They had real grievances, which experience had taught them were impossible of redress through the usual channels, and they thought only of those. They point to assurances given to the public by the commissioner that ample protection would be provided for the city in event of a strike and declare that they accepted these assurances at their face value. If so, the cops pulled a bone.

Two hundred and five members of the policemen’s union served in the Army during the world war; 89 were veterans of the trouble with Spain — to stigmatize men like those as traitors and cowardly deserters seems going it a bit strong. A statement from one of their number, who received the Croix de Guerre, gives their viewpoint. His name is Edward M. Kelleher, Division 15: “I have never been accused of disloyalty or lack of gameness before. Gameness is part of the policeman’s job.”

Passing the Buck of Responsibility

“You say our grievances could have been redressed. I know that. But they were not redressed in 15 years. Now the policeman’s pay has been raised and the stations are to be fixed; the hours even may be made better. But it took a strike to do it. I want to say that I joined the union because we could not get our grievances redressed or even listened to any other way.

“I didn’t want to strike and I don’t know any other man who did want to. I went out when 19 men were discharged by the commissioner because I and the others had elected them officers of the union. They were no more guilty than I was, and I wouldn’t be yellow enough to leave them to be the goats for all of us.

“I wouldn’t have gone on a strike if I had thought the city was undefended and there was going to be a riot. The papers said there were plenty of men to keep order and handle the crowd. The commissioner himself said so.”

However, the measure of their guilt is a matter of purely local concern. Nor has the country at large any special interest in the effort to fix the blame for failure to protect Boston adequately after the police went out. Debate over that point has frequently been of the knock-down-and-drag-out variety in The Hub. The mayor blames the police commissioner and Governor Coolidge; the commissioner has passed the buck to some of the metropolitan park police, who failed to obey orders; the governor and Samuel Gompers had a telegraphic tilt from which Gompers emerged a bad second; the union men assert that the strike could have been entirely averted and the policemen withdrawn from affiliation with the federation if Commissioner Curtis had indicated willingness to meet the men anywhere near halfway; the police feel they were deliberately jockeyed into an impossible position; and charges have been hurled that the whole affair was a frame-up by the capitalistic interests, which desired a showdown at a moment highly favorable to them. Indeed I heard numerous claims that influences were at work to make a test of strength at an opportune time on the general labor situation, entirely apart from the policemen’s union, with an eye to the impending steel strike. Such reports are characteristic of every trouble.

On every side they’ve been denouncing and calling names, and feeling has grown intensely bitter. The inevitable injection of politics into the trouble did not ease the rancor, and the issue livened the gubernatorial contest. Politics has a way of horning into every dispute and capitalizing it, and this is especially true of Boston, whose large population of Irish descent has furnished more politicians to the square yard than any other community in the United States.

Wherever blame may lie, two facts stand out baldly: The police abandoned their posts, and from 6:00 Tuesday night until 8:00 Wednesday morning, Boston remained without protection, a prey to marauding bands of hoodlums. Those occurrences speak for themselves — a grievous blunder was committed somewhere.

A very unusual situation exists there in regard to control of the police. For many years, the police commissioner has been appointed by the governor, an arrangement made during an earlier city administration which did not enjoy public confidence. Boston finds the money to pay the force, but the department is under state control. However, the consensus of opinion appears to be that the scheme worked very well.

The unionizing of policemen had been threatening for two years. Organizers of the I.W.W. stripe and the element in the American Federation of Labor belonging to the same school of thought discerned tremendous possibilities in the affiliation of police unions throughout the country with organized labor. It would give them control of a weapon frequently employed against labor in strikes; in an emergency, they could practically dominate the communities where the police were affiliated; they would have the country by the throat.

The Old Leaders Outvoted

Conservative leaders like Gompers saw all this, but saw also the dangers. They were not blind to the impossibility of winning anything against an aroused and united public, and they perceived clearly that if a police force should strike and leave a city defenseless, the entire American people would clamor for action. In such event, what chance would the federation stand with a sympathetic strike? And yet they would be bound to stick by their brothers. So the conservatives headed off the movement as long as they could. But the wild-eyed factions were persuaded they could throttle the public into granting labor’s demands — or at any rate they were not afraid to try, and they pressed for membership of police unions in the federation. Last June at the convention in Atlantic City, they triumphed. Against the better judgment of the old leaders, it was decided to grant charters to the police. And right there the radicals played hob.

By the time the Boston police had organized, the police forces of 20 cities already belonged to the federation — not without protests and some strenuous opposition from civic officials. But in the main, affiliation took place quietly, and the general public either did not know of it or remained in ignorance of its significance and the menace hanging over them.

The Boston union cannot complain they did not receive fair warning. They did it with their eyes open. As far back as June, 1918, the then police commissioner, Stephen O’Meara, issued a general order setting forth his objections to the organization of a union to be affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, of which there was talk. Commissioner Curtis repeated the warning on July 29 last, and on August 11 promulgated a rule. In this he pointed out it should be “apparent to any thinking person that the police department of this or any other city cannot fulfill its duty to the entire public if its members are subject to the direction of an organization existing outside the department,” and he forbade any member of the force joining any body which was affiliated with any organization outside the department except the Grand Army of the Republic, the United Spanish War Veterans, and the American Legion of World’s War Veterans.

To quote from his and Mr. O’Meara’s arguments: “Policemen are public officers. They have taken an oath of office. That oath requires them to carry out the law with strict impartiality, no matter what their personal feeling may be. Therefore it should be apparent that the men to whom the carrying out of these laws is entrusted should not be subject to the orders or dictation of any organization, no matter what, that comprises only one part of the general public.

“The police department exists for the impartial enforcement of the laws and the protection of persons and property under all conditions. Should its members incur obligations to an outside organization, they would be justly suspected of abandoning the impartial attitude which heretofore has vindicated their good faith against the complaints almost invariably made by both sides in many controversies.

“It is assumed erroneously that agents of an outside organization could obtain for the police advantages in pay and regulations. This is not a question of compelling a private employer to surrender a part of his profits.

“To suppose that an official would yield on points of pay or regulation to the arguments or threats of an outside organization, if the policemen themselves had failed to establish their case, would be to mark him as cowardly and unfit for his position.”

Despite the warnings and in the face of an order forbidding it and an increase of $200 in pay, the police went ahead with organizing their union. They justify their action by the failure of every other means to obtain redress of their grievances. A local organization known as the Boston Social Club had been in existence 14 years, but the police had been unable to win through it improvement in pay and conditions. They contended that this union of their own had fallen under the control of headquarters and was impotent to help them. Nor did they succeed much better with a grievance committee instituted by the present commission.

It has always been the popular belief that a policeman’s job is a sinecure — that he has it pretty soft and easy, with fine pay, little to do and plenty of perquisites. Indeed the notion that policemen could possibly have grievances calling for drastic action roused derision everywhere; sympathy for the Boston cops was nonexistent except among their personal friends. Had anyone suggested to the average citizen that possibly they had a strong case and were not receiving fair treatment, he would have been hooted. The very mention of a cop suggested easy pickings.

Long Hours and Low Pay

But as Boston learned with a shock and to its deep humiliation, the police scale of pay was pitifully low and their hours longer than almost any class of labor. The minimum pay was round $21 a week, and the maximum — reached the sixth year — $31. Out of this, a policeman had to buy a complete uniform and equipment, which cost $207.

The wagon men worked 98 hours a week, the night men did a total of 83 hours a week, and the day men averaged round 73 hours. Pay ran from 21 to 28 cents an hour — and, of course, any sort of labor can command higher rates than those nowadays.

Also, conditions in several of the station houses were deplorable. In the dormitories, beds were used by two and three men in succession during a day and night without being remade.

“At Division Two,” declared John F. McInnes, president of the policemen’s union, “there is but one bathtub for 135 men and only four toilets. Bedbugs, rats, and other forms of vermin roam at will in Stations 9, 13, and 18.”

The police received no extra pay for overtime work. They had to attend every unusual event, like a parade, band concert, or large gathering, and they wanted that considered in their pay. They also objected to delivering unpaid tax bills when it was obviously the duty of a civilian employee, and complained of being forced to do the listing. They condemned the conditions under which civil-service examinations were held and objected to the commissioner reserving to himself the right to promote a man regardless of the showing made in competitive examination.

Those are a few of the grievances which the men assert they could not get redressed. They were news to Boston and gained lots of sympathy for the strikers — without, however, weakening one iota the conviction that the policemen had no right to affiliate with the American Federation of Labor and no right either in law or morals to go on strike. The Hub stands like Gibraltar on that issue.

Not an officer or sergeant of the force joined the union, being ineligible, and many a policeman who followed the crowd did so against his judgment and inclination. They were coerced. As always happens, the leather-lunged aggressive minority practically compelled the others to fall in line. I talked with a striking policeman who had been nine years on the force. He did not want to join the union in the first place, but he could not stand the ostracism which “scab” entails for a nonunion man and his wife and children; and though he was opposed to a strike, he could not leave the others in the lurch after they had decided to walk out.

“How many wanted to go on strike? Less than 50 percent, but a lot were led to vote that way because they didn’t want to desert the boys,” he said.

Another member of the force, who had been with it so many years that he could have retired on half pay in another seven months, joined the union virtually under compulsion, and once in it had to walk out when ordered. And now in his old age he is out of a job and without means of support. What’s more, it is doubtful if he could perform any work but that of a policeman, for when a man has put in many years on a police force, he is unfit for most other jobs. “I didn’t join the union at first,” he said. “But one day I went into the station house and opposite my name on the bulletin board somebody had written in red ink, “Scab.” The kids at school yelled it at my children too. What is a man going to do?”

The Trouble-Making Minority

A minority jammed through unionization of the Boston police and a minority forced the strike, whatever the tally of votes may have showed. It is always the case. In New England less than 25 percent of organized labor is radical, according to those who ought to know. The percentage grows the farther west one goes, yet men who have studied the subject doubt whether 33 percent of the total membership of the American Federation of Labor belongs among the radicals; and organized labor constitutes only 3 percent — or less — of the population of the United States. In other words, about 1 percent of the American people is raising Hades for the other 99 percent and threatening to overturn the institutions in which they believe. It is the realization of this that makes the average citizen grow hot under the collar and sometimes long for command of a firing squad.

Well, the police formed their union and persuaded practically all the men of the force to join it. Charges were soon filed against 19 of them.

“At the request of counsel for the men,” says a statement from Commissioner Curtis, “I heard the cases myself instead of referring them to a trial board. The facts were undisputed. I found the men guilty and delayed imposing the finding, merely suspending them from duty. I did not discharge them because had I done so I would be without power to reinstate them at any time. Instead of taking the opportunity which was thus open to save their positions, the majority of the force deliberately deserted and abandoned their duty and the city which they had sworn to protect.”

Threats of a strike if the members of the union under charges should be suspended were freely made before their cases came up for hearing. In view of the gravity of the prospect, Mayor Peters appointed a committee to investigate the trouble and act as mediators, and endless negotiation and argument and conferences followed. This committee did their utmost, but to no avail. Their executive committee succeeded in drawing up a plan to which the tacit consent of the policemen was given, but the commissioner could not see his way to accept it. The plan received Mayor Peters’ endorsement, and the committee which presented it was composed of well known Bostonians —James J. Storrow, B. Preston Clarke, George E. Brock, P.A. O’Connell, James J. Phelan, A.C. Ratshesky, and F.S. Snyder. Briefly, it provided that the policemen should give up affiliation with the American Federation of Labor but maintain a union within the department to deal with questions relating to hours and wages and physical conditions of work; called for an investigation of the police demands and grievances by a committee of three citizens, which should continue to act as a sort of court of arbitration; and stipulated that no member of the force should be discriminated against because of any previous affiliation with the American Federation of Labor — neither should there be any discrimination on the part of the policemen’s union against any member of the force because of refusal to join.

The main objection to the plan, of course, was that it gave immunity to the ringleaders in the unionization of the police. Anyhow, the commissioner would not agree to it; the 19 policemen were suspended; and after taking a vote, about 1,400 policemen made good their threat to strike.

Everybody knows what happened after that. The spectacle of Boston given over to lawless mobs shook the whole country. President Wilson denounced the strike as a crime against civilization, and Elihu Root told the National Security League: “What does the police strike in Boston mean? It means that the men who have been employed and taken their oaths to maintain order and suppress crime as the servants of all the people are refusing to perform that solemn duty unless they are permitted to become members of a great organization which contains perhaps 3 percent of the people. Now, if that is done that is the end — except for a revolution. Government cannot be maintained unless it has the power to use force. If the power to use force passes from the 97 percent of the whole people of the United States to this organization of 3 percent, the 97 percent are no longer a self-governing people.”

The 97 percent were quick to take alarm — and up to date they give every indication of maintaining self-government! The whole country blazed into resentment. If policemen could join the American Federation of Labor and go on strike, leaving their communities helpless, where would unionization end? The police in a score of cities were watching the outcome. Already many fire departments were affiliated with the American Federation of Labor; what if they should strike too? What of sympathetic strikes? And if the police could owe allegiance to a union, why not the Army? Where would it all end? In soviet government? A night of rioting in Boston woke the United States to the real nature of the menace.

The Governor’s Reply

Even labor-union men condemned the walkout. They might uphold the right of the police to affiliate with the American Federation of Labor, but when the consequences endangered the safety of their own families and property and threatened to make them jobless through general demoralization of business, they realized that it was carrying the thing too far. Tying up the public was one thing; letting anarchy loose was another.

The bulk of organized labor disapproved of the cops’ action. Only the newer membership of the unions supported them and favored a sympathetic strike. As a lot of new members had been admitted into the union of the car men on the elevated, a ticklish situation was produced, but aside from this union and the telephone operators, who voted to strike, organized labor blew cold on the proposition.

And what about the federation? Gompers realized immediately that the policemen’s case was hopeless and sought to exert pressure to the end that the men might be taken back and all action against them suspended until after the labor conference in Washington in October. To this request Governor Coolidge of Massachusetts made a reply which struck a responsive chord in every corner of America and lifted him into national prominence overnight:

“The right of the police of Boston to affiliate has always been questioned, never granted, is now prohibited. The suggestion of President Wilson to Washington does not apply to Boston. There the police have remained on duty. Here the Policemen’s Union left their duty, an action which President Wilson characterized as a crime against civilization.

“Your assertion that the commissioner was wrong cannot justify the wrong of leaving the city unguarded. That furnished the opportunity, the criminal element furnished the action. There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.

“You ask that the public safety again be placed in the hands of these same policemen while they continue in disobedience to the laws of Massachusetts and in their refusal to obey the orders of the police department. Nineteen men have been tried and removed. Others having abandoned their duty, their places have under the law been declared vacant on the opinion of the attorney general. I can suggest no authority outside the courts to take further action.

“I wish to join and assist in taking a broad view of every situation. A grave responsibility rests on all of us. You can depend on me to support you in every legal action and sound policy. I am equally determined to defend the sovereignty of Massachusetts and to maintain the authority and jurisdiction over her public officers, where it has been placed by the constitution and laws of her people.”

I asked Governor Coolidge whether he thought the American Federation of Labor had advised or sanctioned the strike. “The federation has never advised a strike there was no hope of winning,” he replied cautiously.

I asked one of their counsel whether he had done so.

“No, I advised against it,” Mr. Vahey declared earnestly. “They had already affiliated with the federation before I was called in, but both Feeney and I urged them to give up their membership in it. We told them we could get more for them than they could through the federation. But they stuck. When their leaders were suspended the men had to stand by them.”

Mayor Peters had received assurances that ample protection for the city would be available in the event of a police strike. Consequently the tangle was left to the police commissioner, and statements from the department persuaded the public that the situation was well in hand. He had at his disposal all the sergeants and officers of the force; also a hundred men of the Metropolitan Park Police, an organization distinct from the Boston department.

Such was the official force the commissioner could count on, and it seemed adequate to him. For the protection of the banking houses and large business establishments of the city, bodies of guards had been organized privately, and these were supplemented by hundreds of volunteers who offered their services as patrolmen.

In fact big business and the larger mercantile concerns had prepared fairly well for eventualities. But Boston hadn’t guessed a tenth of what those eventualities would be.

The police went out before six o’clock on a Tuesday night. Several hours later the scum of South Boston and the West and North End were on a rampage. Scollay Square, the district between Boylston and School streets, all along Washington and Tremont streets, echoed to the crash of glass as the mobs of rowdies and thieves looted where they willed.

The Shop-Window Raiders

A crowd of more than 5,000 persons gathered in the vicinity of Broadway in South Boston, and when charged by about 50 of the park police met them with a barrage of stones and sticks and bottles and eggs. The rioters rocked the streetcars and stoned some loyal patrolmen of D Street station who had declined to go on strike.

Long before midnight, the mobs held undisputed possession of the streets. With nobody to hinder, huge bands of hoodlums went prowling through the heart of the city, holding up any unlucky pedestrians who came their way and pillaging stores which caught their fancy. A swift kick on a plate-glass window, then a scramble for the spoils.

“At about 12:30 we heard a far-off sound of smashing glass,” said a former newspaper editor, who was on guard at a fashionable specialty shop, “like the tinkle of a toy bell. After a while we saw a mass of people swing out of Avery or Mason Street into Tremont. There wasn’t any noise. They were walking along at a moderate pace — perhaps two miles an hour — and saying nothing. All of them were young — mere boys — averaging from 18 to 20 years, I should say. And they were entirely sober. We did not see a single drunk that night. There were no women, but a few waited on the other side of the road, perhaps out of curiosity. A large battered automobile was creeping along close to the curb.

“Suddenly came a crash of glass. They had demolished a window and were going after the stock inside. We could see them surrounding the store and hauling out stuff. A taxi or two, devoid of lights or numbers, stopped across the road and men inside them got their share of plunder. Quite a few taxis operated in this fashion during the night.

“Approaching us, the crowd left the sidewalk and took to the gutter and middle of the road. They slowed down opposite and we heard, ‘Let ’er go ! Let ’er go!’ However, no bricks were heaved. Somebody yelled, ‘Whatcha got in your hand, Jack?’ for we kept our hands in our pockets. I answered, ‘On your way!’ And after loitering a moment longer somebody cried, Ah, come on! He looks like a pretty good guy!’ And the whole mob drifted.

“Later 25 or 30 men came to us in groups of two and three. They all came for one purpose — to advise us to take our goods out of the windows and draw the curtains. They said they had followed the crowd to see the fun.

“Back came the battered automobile, too, and slowed down in front of the store. ‘Say, youse guys can thank Gawd you was in front of your place when the gang came.’

“The crowd acted without any set plan. At five in the morning I walked a mile along Washington Street and in the West End to see the havoc. I found the same sort of haphazard looting everywhere — one shop battered at this point and another close by, much richer in possibilities, unharmed. What the merchants and financial concerns feared was a quick rough-stuff job by a party of motorists. Cars without lights were scudding up and down all night; I saw one pass our place five times apparently scouting for chances.”

Crap Games on the Common

Crap games started early in the evening and were in full swing on the sacred soil of Boston Common before 7:00. Headquarters was on the paved walks across from the Park Street Church, the famous “Brimstone Corner” of other days. No police or patrols to bother them, the crap shooters displayed a total disregard of the throngs of spectators and pleaded for Big Dick and Little Phoebe according to their needs with the passionate earnestness they would have put into a game in the lane back of the garage.

And next day — oh, boy! Boston became a wide-open town for gamblers. Crap shooting everywhere; staid citizens stumbled over games en route to business, heard the click of the bones in the lobbies of their office buildings. There were even roulette wheels in operation in broad daylight in the open air. And they were not all pikers’ games by any means. In many a gathering men were shooting for $10 a throw.

An incident occurred at one of the games on the Common which is illuminating. A player of the tough-mug variety — one of those guys who talk out of the sides of their mouths — won $40 and became wishful to retire. Evidently he anticipated trouble in getting away with his roll, for he pulled a gun, and holding the money in one hand while he covered his companions with the weapon, backed slowly away. Once law and order are broken down there is no security even for those who did the wrecking.

A night of unbridled hoodlumism was followed by a day of rioting, of fights and thievery, accompanied by considerable property loss, assaults on women, and several casualties. The losses were much exaggerated in the press reports and probably did not exceed $50,000, for there was no organized looting. One of the youths charged in court with larceny of six shoes had the stolen property on him — and not a pair in the lot.

After grabbing some shoes or shirts, a boy would sell them to another member of the mob for 25 or 50 cents. And the novel sight was witnessed of rowdies gravely fitting stolen shoes to one another’s feet while they sat on the sidewalk.

Business concerns took steps to fortify their places against possible raids. Some shops became veritable arsenals. I saw one with barbed-wire entanglements across the entrances at night; wire and all metal trimmings round the door were charged with electricity. Windows were stoutly boarded. Inside a force of guards stood ready, with a system of alarms designed to meet any emergency, powerful arc lights to blind any intruders, and rifles, revolvers and riot guns available for instant use. To supplement these defenses they had a fire hose all set. It would have taken trained troops to storm the place.

For several days no goods were displayed in the windows or showcases of the principal stores. Retail trade was paralyzed. Owners of valuables stored them away in vaults or other safe places. It seems remarkable that no really high-priced stuff was looted the first night. Rich furs and dress goods, silks — all manner of articles which would tempt a professional thief with a knowledge of values — escaped. And they grabbed shoes and cheap jewelry and shirts and umbrellas!

Equally remarkable is it that there was no incendiarism — plenty of false alarms, but no fires. Boston began to speculate about a week later on what might have happened had booze been on sale in the city.

It would take too long to tell all that happened before order was restored, but as Bill Hamilton once remarked in an account of proceedings after a bum decision at a prize fight, “pantomime reigned.” Besides old families and men and women of culture and breeding, besides safe and sane business men, a conservative professional class, and a labor population which is substantial and self-respecting, Boston possesses in considerable numbers a red-necked type which is always eager for a fight and packs a wallop in either hand. And these gentry had free run of the city.

Things became so bad that troops were called out and the Massachusetts State Guard took over the policing under Brigadier General Samuel D. Parker. The mayor is empowered in case of tumult or riot to take over the police department, which Mr. Peters did on Wednesday morning. He called out that part of the State Guard living within the city limits, but their number being totally inadequate, it became necessary to call all the State Guard throughout the commonwealth. Authority for this action rested in the governor, and accordingly Mr. Coolidge took charge of the situation, reinvesting police authority in Commissioner Curtis and instructing him to obey only such orders as the governor might issue.

The State Guard is equivalent to the Home Guards and is composed of men who volunteered for duty to replace the National Guard when it was called into service during the war. Most of them are either above or below draft age or had disabilities which prevented their going into the Army, and they come from all walks of life. You can find wealthy men in the State Guard, and college professors, and boys just beginning to use a safety razor.

These troops were distributed about the city, with a strong force held in reserve for emergency. They patrolled the streets and did guard duty, kept everybody moving, permitted no sidewalk conversations and made scores of arrests. Also they killed a few who resisted the enforcement of law. In spite of their three-speed rifles — you have to cock them three times, but luckily there is no reverse — the State Guard proved themselves efficient troops and handled the troubles firmly.

The Cooper Street Riots

Commissioner Curtis told me that crime dropped 50 percent below normal as soon as they brought in the soldiers to restore order. And I was able to see for myself the salutary effect the presence of the guard had on soapbox agitators and Bolshevik windjammers. They had been fond of street meetings, but evidently something told them that the time was not propitious for incendiary talk. You couldn’t have found a soapbox orator with a search warrant after the troops got on the job.

Soldiers were quartered in Faneuil Hall, the Cradle of Liberty. But according to C.H. Eveleth, who was a schoolboy in Boston in 1863, it was not the first time the Cradle had been used for a barracks.