What was America’s First Successful Book Series?

In the portfolio of a company’s offerings, there are no crown jewels more prized than the franchise. The roots of serial storytelling stretch all the way back to oral tradition, but the birth of publishing built on that tradition of long-term narratives and allowed them to flourish. That leads to two questions: what was the first completely American novel sequence to capture the attention of the young U.S., and how does it connect to, you guessed it, The Saturday Evening Post?

Many literary historians agree that the first real novel sequence was the French work Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus (usually called Artamène or Cyrus the Great in English). The first volume was published by Georges de Scudéry in 1649, though his sister Madeleine was the actual author, or at the very least, a significant co-author. The siblings put out ten volumes of the story, which cast contemporary people in roles associated with stories from myth and religion. At over 13,000 pages and nearly two million words, it remains one of the longest works of its type ever published.

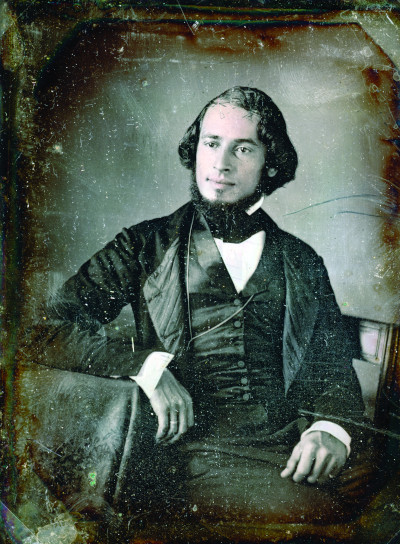

Moving on a couple of centuries, we find James Fenimore Cooper. Born in New Jersey just days after the end of the Revolutionary War, he started at Yale when he was thirteen, but was kicked out for a pranks like locking a donkey in a classroom and destroying the door to a fellow student’s room. However, Cooper turned his youthful ways around and became an officer in the United States Navy. In 1811, he married Susan Augusta DeLancey.

The marriage would have a profound impact on Cooper’s direction in life, as a couple’s activity led to a major career change. While reading a novel aloud to his wife (as family reading was a common diversion at that time), Cooper realized that he had his own interest in storytelling. That revelation led to the writing of his first book, Precaution. The book was issued anonymously in 1820 and was well-received in both England and the U.S. His next book, 1821’s The Spy, turned out to be a major success, establishing him as the first American bestselling author; based on stories told him by his neighbor (and United States Founding Father) John Jay, Cooper’s The Spy combined two things that would be at the forefront of his most successful works: historical settings and action.

Cooper’s third novel would mark the beginning of a landmark series. 1823’s The Pioneers introduced readers to Nathaniel “Natty” Bumppo, also known by such names as Leatherstocking and Hawkeye, and his close Mohican friend, Chingachgook (who sometimes uses the name John Monegan). First appearing on the page as old men, Bumppo and Chingachgook have rich histories as scouts who help the settlers in the area. Cooper may have based Bumppo on the exploits of frontiersman Daniel Boone, who was already an American folk hero.

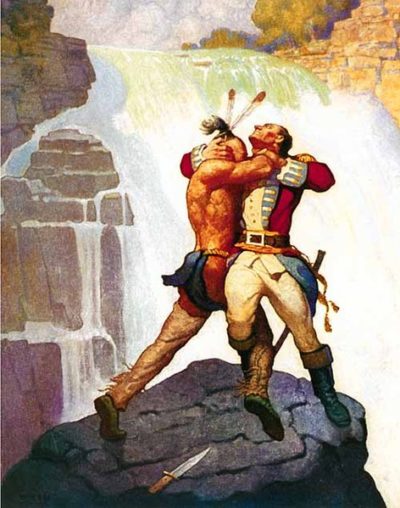

Though he would continue to write a diverse array of material including nonfiction history, Cooper returned to Bumppo and Chingachgook four more times between 1826 and 1841. The novels did not arrive in chronological order; rather, they skipped up and down the timeline of Bumppo’s life. While The Prairie, The Deerslayer, and The Pathfinder would all find popular success, it was the second book (both in terms of release and in the series continuity), 1826’s The Last of the Mohicans, that would prove to be Cooper’s most popular and enduring work.

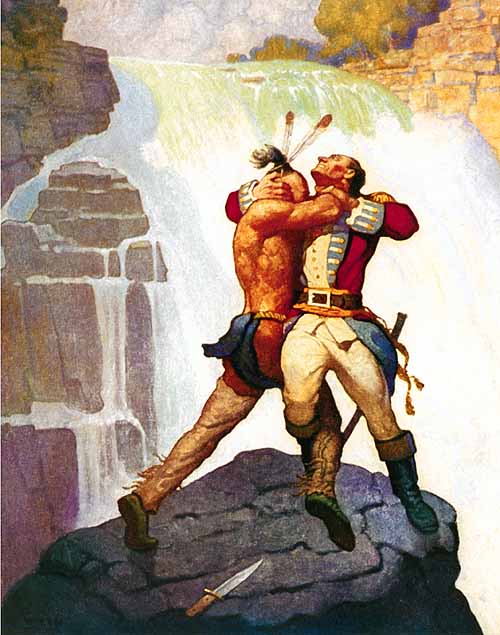

The Last of the Mohicans took place around 1757 during the French and Indian War, which is the name typically associated with the battles of the Seven Years War between England and France that occurred in North America. During the conflict, both countries enlisted Native American tribes as allies to support the troops that each had landed on the continent. Settlers along the frontier who had arrived from England or were descended from earlier settlers frequently fought in England’s colonial militias. It is against this backdrop, and the historically accurate siege of Britain’s Fort William Henry by the French, that Cooper set his novel.

The Last of the Mohicans (1992) trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by TrailersPlaygroundHD)

The main events of the plot concern Hawkeye, Chingachgook, and Chingachook’s adult son Uncas guiding and protecting Cora and Alice Munro, the daughters of British Colonel Munro. British Major Duncan Heyward and singing master David Gamut are also part of their party, who frequently come in conflict with the Huron chief Magua, a secret ally of the French. The wilderness adventure aspect of the tale, combined with historical events, made the book extremely popular. Magua was one of the early, effective villains of American literature, and the story cemented the three central companions as significant heroes to the audience. Since 1909, there have been at least 10 American film adaptations of the work, as well as versions made for radio, television, comics, and opera; such is the story’s reach that it’s also been adapted for film in Europe several times, once as a German silent version in 1920 that featured Bela Lugosi (yes, you read that right) as Chingachgook.

Apart from his extremely popular Leatherstocking series, Cooper’s output was very diverse. He often infused his stories with social and political commentary, whether he was writing about maritime adventure or history. As an admirer of Thomas Jefferson, and a writer who wove that admiration into his work, Cooper often came under attack from political opponents in the Whig party. Cooper regularly sued his attackers for libel and won, which only created more enemies. The author more or less shrugged his shoulders and soldiered on. In additional to his novels, he published an array of short fiction, some of which ran in The Saturday Evening Post (including “Life Before the Mast,” which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1843; you can read that story below).

When Cooper died in 1851, a number of famous fellow writers took it upon themselves to make sure that he was remembered for his expansive work. Everyone from Henry David Thoreau to D.H. Lawrence praised him, and Washington Irving spoke at one of his memorials. Over time, most of his works have faded from popular awareness, but the Leatherstocking Tales, particularly The Last of the Mohicans, carved out a seemingly immortal space. Cooper proved that a wholly American series of fiction could find popular success not only in his home country, but around the world. It’s appropriate that he wrote about guides and pioneers, because he opened a whole new frontier for American writers to explore.

The Earliest Photo of Native Americans

On a cold day in late November 1853, in a place called Big Timbers, in what is today southeastern Colorado, a Jewish photographer named Solomon Nunes Carvalho hoisted his 10-pound daguerreotype camera onto a tripod and aimed his lens at a pair of Cheyenne Indians. At first glance, the resulting image, scratched and faded from years of neglect, seems unremarkable. But in fact it is probably the oldest existing photograph of Native Americans taken on location in the Western United States. It’s the sole surviving daguerreotype from an unprecedented and extraordinary photographic journey. And for me, a filmmaker chronicling Carvalho’s incredible but little-known story, it ultimately provided a powerful spiritual bridge to the past.

Carvalho was 38 years old and an unknown portrait artist and daguerreotypist when he received an offer from Col. John C. Fremont, the most famous adventurer of the day, to serve as the official photographer of Fremont’s Fifth Westward Expedition. For years, Fremont had been consumed with mapping a route for the transcontinental railroad. He had always included a sketch artist among his crew, but this time he wanted to use photography, a new technology, to document the terrain.

An urbane city dweller raised in Charleston, Carvalho had never traveled West or even saddled his own horse.

It was a risky proposition. Fremont’s previous foray had ended in disaster when 10 men froze to death in the Rockies, and Carvalho was totally unprepared. An urbane city dweller raised in Charleston, South Carolina, he had never traveled West. In fact, he had never even saddled his own horse. No daguerreotypist had ever attempted anything like this before. Daguerreotopy, which was the earliest form of photography, had only been invented 14 years earlier in 1839. It was a cumbersome process involving polished, silver-coated copper plates and lots of gear and chemicals, and it was prone to failure. Of the handful of professional daguerreotypists in the United States, nearly all worked indoors, shooting portraits. Capturing wide landscapes in extreme weather conditions was almost unheard of.

Yet two weeks after accepting Fremont’s offer, Carvalho set out, with a seasoned group of explorers, teamsters, hunters, and guides. It would be the journey of his lifetime. The team included white Americans, a German, a few Mexicans, 10 Delaware Indians, and of course Carvalho, who was an observant Sephardic Jew of Spanish-Portuguese descent. From the very start, the group faced challenges: torrential rains, raging prairie fires, injuries, infighting. Col. Fremont became injured early on and had to turn back to seek medical attention. After a six-week delay, Fremont rejoined his men in Western Kansas and then led them, perhaps foolishly, toward the Rocky Mountains just as winter was about to set in.

Along the way, Carvalho dutifully worked at his craft and, against the odds, succeeded in capturing image after image of the landscapes, buffalo, and the expansive terrain of the West.

The expedition encountered the Cheyenne village at Big Timbers in late November, during a supply stop along the Santa Fe Trail. It wasn’t easy photographing the Native Americans, Carvalho found. “I had great difficulty in getting them to sit still, or even submit to having themselves daguerreotyped. I made a picture, first, of their lodges, which I showed them,” he later wrote.

Carvalho’s daguerreotype of Big Timbers shows a pair of teepees nestled up against the edge of a forest of tall pines. Atop a thicket of logs and tree branches, several skins or hides are set out to dry. Two human figures, faded to an almost ghostly pallor, anchor the image in time. Their faces are hard to make out, but one has long braids and both are dressed in traditional native outfits.

Princeton historian Martha A. Sandweiss, an expert in photography of the American West, credits Carvalho with creating a painstakingly deliberate scene. “Carvalho sensed he needed to preserve a certain amount of information,” she told me in an interview. “He stepped back from the scene, and he has carefully framed the image. He’s not doing a close-up, at least in this picture, of the two people, or of the teepee, or of a piece of meat on the ground. He’s trying to show us something about native life.”

Fremont was thrilled with Carvalho’s work. “We are producing a line of pictures of exquisite beauty, which will admirably illustrate the country,” he wrote to his wife, Jessie Benton Fremont. He described the pictures of Big Timbers as “jewels.”

“I had great difficulty in getting them to sit still,” wrote Carvalho about the natives he photographed.

Sandweiss believes the daguerreotype tells us as much about the photographer as it does the subject. “I think what we see in this picture is evidence of a collaboration. It’s important to remember that Carvalho was working with a camera on a tripod. This is not a snapshot. These Indian subjects knew they were being photographed, and they are looking Carvalho in the eye.”

Of the 300 or so daguerreotypes Carvalho made on the expedition, this image is the only survivor.

After the expedition, photographer Mathew Brady’s New York studio converted Carvalho’s daguerreotypes into hand-drawn printing plates, so they could be turned into etchings and published. At the time, converting photographs to etchings was the only way to reproduce them for large numbers of people to see. It seems inconceivable to us today, but at that early time in photographic history, the daguerreotypes themselves were considered worthless — just a means for carrying back visual information that would be enshrined forever on a steel printing plate. Years later, they ended up in a storage unit belonging to Fremont and were destroyed in a fire in 1882 — gone forever, and barely missed. The Big Timbers daguerreotype somehow, luckily, ended up in Brady’s personal collection, which now resides at the Library of Congress.

The 60-odd surviving etchings made from Carvalho’s daguerreotypes tell a spectacular story of discovery, but the one surviving image does more: It provides a spiritual connection to the past. For most of the years I worked on my documentary film, Carvalho’s Journey, I relied on various reproductions of the Big Timbers image. I finally had a chance to see the real thing during a visit to Washington, D.C.

It is smaller than I had imagined, just four by five inches. In real life, the damage is worse than in reproductions. But holding it in my hands, I was struck by an intense proximity to history. This piece of copper was the same tool that miraculously captured the Cheyennes’ likenesses, their teepees, their hides drying on the line. It was the same bit of metal that an urbane, Southern-Jewish photographer carried thousands of miles on horseback and heated over a fire to develop. The moment captured on the plate, faded as it is, was the exact image Solomon Carvalho saw that day. Native people who had never seen a photograph before — and whose lives would never be the same after their collision with Europeans — would have seen it too. It was the vessel through which an unlikely visitor and a pair of Indians faced each other and forged a quintessentially American encounter.

Daguerreotypes, which are in many ways an art form lost to history, are reflective just like mirrors. On one as faded as Carvalho’s, the mirrored surface makes it almost impossible to see the image detail when you look directly at it. You instead see yourself, peering into it, looking into history.

Steve Rivo is a documentary filmmaker and television producer. He is the writer and director of Carvalho’s Journey (2015). More info at www.carvalhosjourney.com. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: A glimpse of the past: The only surviving daguerreotype from Solomon Nunes Carvalho’s 1853 journey west depicts a view of the Cheyenne village at Big Timbers. Two figures stand to the left; drying hides hang on the right. (Library of Congress)

Considering History: The Washington Redskins, Oklahoma Territory, and the Myth of the “Vanishing Indian”

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

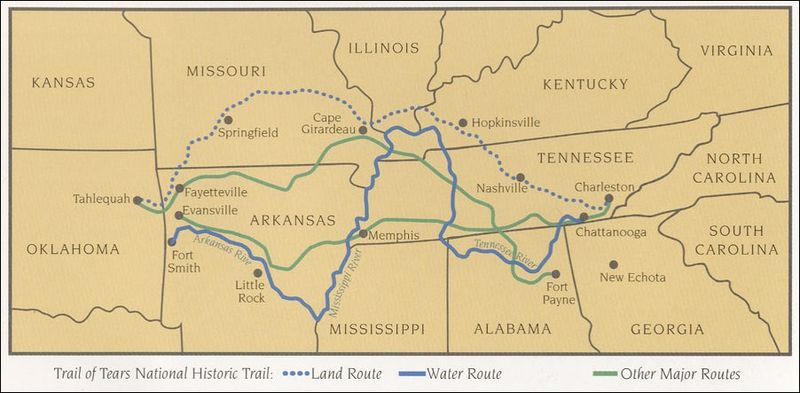

Recently, we have seen two striking decisions on longstanding issues connected to Native American communities. On July 9, in one of its last announced decisions of this session, the Supreme Court ruled that the eastern half of the state of Oklahoma remains “Indian territory” under 19th century treaties that guaranteed the land for tribes forced west on the Trail of Tears, treaties that have never been amended by Congress and so (the Court ruled) continue to hold today. And on July 13, the NFL franchise the Washington Redskins formally announced that the team will be changing its nearly century-old racist name and logo.

The details of these two decisions are quite specific to their respective arenas, and reflect evolving conversations in each case. But taken together, they exemplify two longstanding and contrasting national narratives: those which depict Native Americans through reductive, stereotypical images in order to justify attempts to expel and destroy native communities; and those which recognize instead Native Americans’ foundational and continued presence within America.

In order to justify his proposed, genocidal Indian Removal policy which produced the Trail of Tears, President Andrew Jackson depicted Native Americans through such stereotypical and racist imagery, defining them as savages unable to coexist with European-American communities or indeed exist at all within the expanding Early Republic United States. In his December 1829 first President’s Annual Message to Congress, Jackson argued that “this fate [disappearance] surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the States.” And in his December 1833 fifth annual message, Jackson went much further, claiming, “That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain…Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

Jackson’s more aggressively racist depictions of Native Americans were complemented by a gentler and more insidious exclusionary perspective that came to be known as the “Vanishing Indian” narrative. Often advanced by figures and communities sympathetic to native rights, this narrative relied on images like the admirable but doomed “Noble Savage” to depict Native Americans as tragically but inevitably disappearing from the continent. James Fenimore Cooper’s bestselling historical novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826) illustrates this trope, arguing from its title on that its heroic Native-American characters are the “last” of a tribe that in fact still existed in Cooper’s era (and still does in our own). Poet Lydia Huntley Sigourney’s “Indian Names” (1834) is even more striking, as Sigourney uses the persistence of Native-American names on the American landscape to angrily (and inaccurately) lament the destruction of native communities: “Ye say they all have passed away,/That noble race and brave/… But their name is on your waters,/Ye may not wash it out.”

The “Vanishing Indian” narrative became a dominant trope across the 19th century and into the 20th, and in subtle but significant ways informed numerous prominent cultural works, as illustrated by Wellesley Professor Katharine Lee Bates’s 1893 poem “America” that became the lyrics for the song “America the Beautiful” (1910). That trope is most apparent in Bates’s second verse, where she describes America’s origin point: “O beautiful for pilgrim feet/Whose stern, impassioned stress/A thoroughfare for freedom beat/Across the wilderness!” But Bates likewise disappears Native Americans from the idealized images of the national landscape with which her poem opens, and which were inspired by a cross-country train trip from her Massachusetts home to a summer teaching job in Colorado. Bates originally named her poem “Pike’s Peak,” as she wrote it after a day trip ascending the mountain — but, like that name itself, her poem leaves no place for the Ute and Arapaho tribes who had been part of that landscape long before explorer Zebulon Pike arrived.

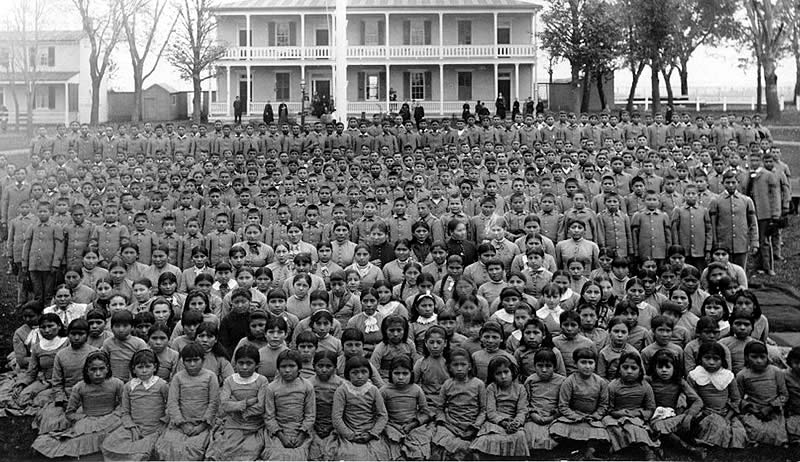

Bates’s 1893 trip took place just two-and-a-half years after the December 1890 Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, an exemplification of the far more violent exclusionary attacks upon Native-American communities that continued throughout the 19th century. The late 19th and early 20th century also featured another, even more insidious form of cultural genocide designed to facilitate the disappearance of Native-American cultures: the boarding school movement, which (as Carlisle Indian Industrial School founder and former “Indian Wars” Captain Richard Pratt put it) was intended to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Both these military and educational efforts illustrate that the “Vanishing Indian” was not just a cultural image, but also and most importantly an ongoing white supremacist goal.

As I wrote in this October 2018 Considering History column, Native-American activists and communities have consistently used legal and political means to challenge such attacks and advocate for their survival and their rights. In response to Jackson’s Indian Removal policy the Cherokee nation did so forcefully, with the tribe’s leaders drafting a series of “Cherokee Memorials” to the U.S. Congress that were published in the tribe’s newspaper The Cherokee Phoenix and submitted to Congress to request their assistance. The Cherokee also took their claims to the court system, and the Supreme Court sided with their rights to their land in the Worcester v. Georgia (1832) decision. Jackson famously ignored the Court and proceeded with removal.

Native-American legal and political efforts continued for the next century-and-a-half, including the two prominent moments I highlighted in my earlier column: Ponca Chief Standing Bear’s legal challenge which resulted in the groundbreaking 1879 decision that “an Indian is a person” for purposes of the law (and otherwise); and the numerous activists, including Zitkala-Ša and Nipo Strongheart, whose advocacy led to the watershed 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

The 1960s and 1970s American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis in 1968, continued to utilize the political and legal system to advocate for native lives and rights, while fostering the Red Power and Native-American Renaissance cultural movements of late 20th century America.

These destructive myths and their effects have endured, as illustrated by the horrifically high numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths on Native-American reservations — one more way (among too many, including the kidnappings and murders of native women and the destruction of native lands for pipeline construction) in which native communities continue to face the threat of disappearance. But the Supreme Court decision embodies a perspective in which Native-American rights and presence are seen and supported, and where native communities are defined as foundational and integral parts of America’s history, identity, and future.

Featured image: The delegation of Sioux chiefs to ratify the sale of lands in South Dakota to the U.S. government, December1889 / photo by C.M. Bell, Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

Considering History: William Lloyd Garrison — An Activist Ahead of His Time

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

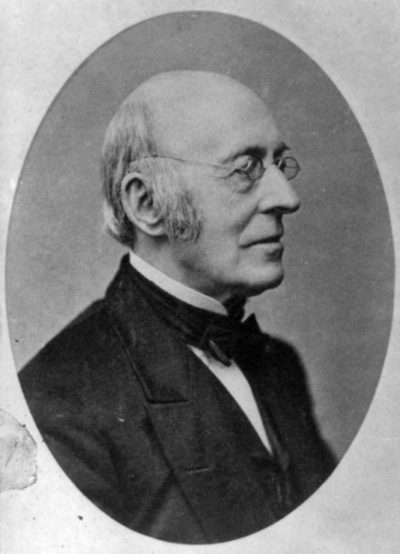

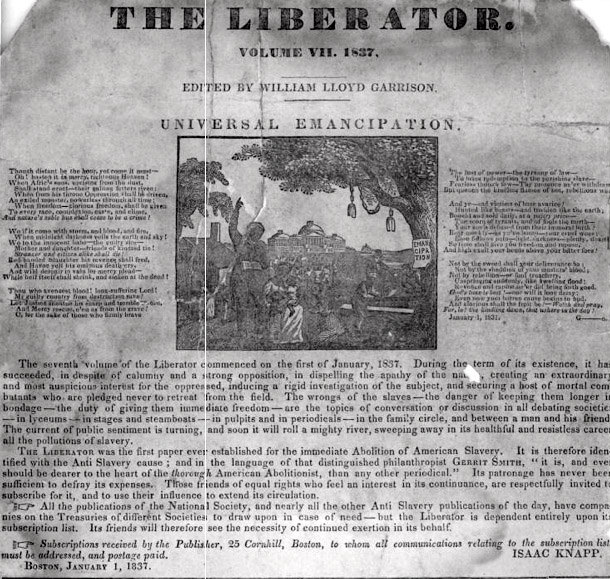

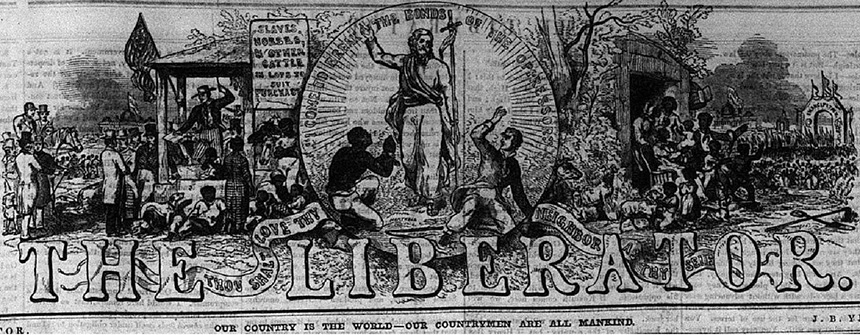

On December 10, 1805, William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts. The son of immigrants from New Brunswick, Garrison would grow up to become one of America’s most prominent and influential journalists and abolitionists. For nearly three decades, from its 1831 founding through the end of the Civil War, his Boston-based newspaper The Liberator served as a primary medium for the anti-slavery movement.

Yet if we focus only on Garrison’s abolitionism, we miss many other key elements of his life, elements that embody his consistent support for fellow activists, particularly those in less privileged positions. Garrison was ahead of his time in modeling an impassioned, inclusive, intersectional activism that applies to our 21st century moment.

Even Garrison’s signature abolitionism was significantly more courageous and inspiring than it might seem. From the vantage point of 2019, an anti-slavery perspective might appear to have been a popular and even fashionable attitude to hold in the antebellum North, as the divide between the North and the slaveholding South deepened throughout this period. But the truth is quite the opposite—even (perhaps especially) in the North, abolitionism was a deeply unpopular and dangerous position to hold throughout the pre-Civil War decades.

Garrison experienced those dangers first-hand, early in his career as a public abolitionist. On October 21, 1835, he addressed a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Nearly 2,000 angry Bostonians surrounded the building, and when Garrison sought to escape, they captured him, dragged him through the city streets by a rope tied around his waist, and planned to tar and feather him (an occasionally fatal and always brutal form of vigilante justice). Boston Mayor Theodore Lyman (himself no abolitionist but an opponent of mob violence) intervened to save Garrison, but for many months thereafter mobs burned Garrison in effigy and constructed a mock gallows in front of his home. Yet Garrison never relented from his public, vocal stance on abolitionism.

In January 1834, nearly two years before that Boston attack and less than three years into The Liberator’s existence, Garrison used his paper and public position to support another oppressed American community. As I highlighted in my last Considering History column, the Mashpee Native American tribe were in the midst of their revolt, a legal and social challenge to both neighboring white communities and the Massachusetts political and power structures. They desperately needed allies in their quest for rights and sovereignty, and after Mashpee representatives addressed a special session of the state legislature on January 21, 1834, they found such an ally in Garrison. Three days later he wrote an editorial supporting Mashpee, a public stance that helped them find additional allies and contributed to the legislature’s March 1834 vote in the tribe’s favor.

In addition to his abolitionism and support of Native Americans, Garrison was also an early and passionate advocate for the women’s rights movement, announcing in December 1837 that The Liberator supported “the rights of woman to their utmost extent,” appointing women to leadership positions within both the Massachusetts and American Anti-Slavery Societies (each of which he had helped found and continued to lead), and helping organize and direct the first national Women’s Rights Convention, held in Worcester in October 1850. While many of his fellow male abolitionists disagreed, leading to the formation of a competing American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (which did not allow female members), Garrison held firm to the position that abolitionism and women’s rights were intertwined movements.

Garrison’s activism extended to other causes as well. He was a vocal opponent of state executions, using the prominent 1849 case of Washington Goode, an African-American sailor sentenced to hang for murder, to argue against the practice of capital punishment on the whole. He would go on to link that cause to the broader movement for prison reform, supporting his fellow Massachusetts abolitionist Dorothea Dix in her quest to challenge both the prison system and societal attitudes toward the mentally ill. The first newspaper Garrison edited, the Boston-based National Philanthropist, had advocated principally for the temperance movement, and Garrison likewise continued to support that movement throughout his career, linking that cause to women’s rights, legal and prison reforms, and other issues.

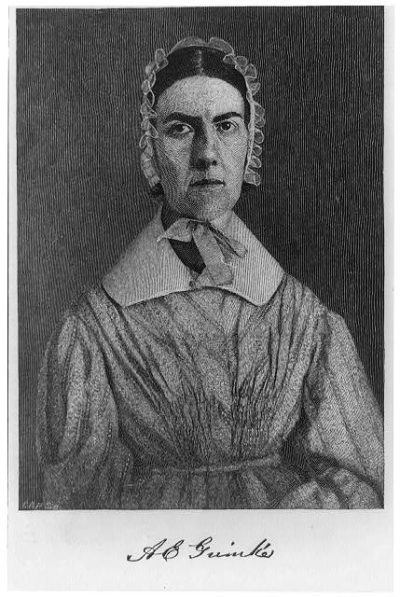

On all these and many other social movements, Garrison held strong opinions and was never shy about expressing them. But the second consistent element of his activism was his willingness to promote the voices of fellow activists, especially those from minority and oppressed communities. He launched his public support for the women’s rights movement by publishing two female activists and abolitionists, the South Carolina sisters Angelina and Sarah Grimké; Garrison printed Angelina’s “Letter to Catherine E. Beecher” and Sarah’s “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman” in The Liberator and then published them as books. In his final decade of life he was still working to share the work of female activists, both as an editor of the newly founded suffrage newspaper Woman’s Journal and in his role as president of the American Woman Suffrage Association.

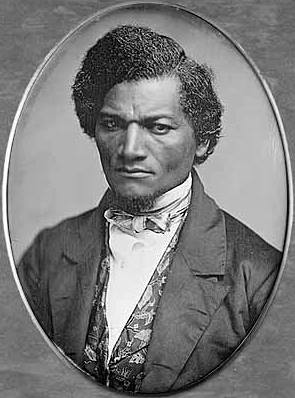

Garrison also supported the voices and work of African-American activists. Exemplifying those efforts was his friendship with and advocacy for Frederick Douglass. Garrison wrote about Douglass’s nascent abolitionist activism in The Liberator in 1839, less than a year after Douglass’s escape from slavery, and in 1841 invited Douglass to speak at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s convention on Nantucket. He would go on to help secure publication for and write a Preface to Douglass’s first book, his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Late in life, Douglass would write that “no face and form ever impressed me with such [abolitionist] sentiments as did those of William Lloyd Garrison,” and that “his paper took a place in my heart second only to the Bible.”

Garrison occupied a position of privilege, but he used that position and privilege to risk his life in support of his fellow Americans, to model activism for a variety of intertwined causes, and to amplify the voices and work of less privileged activists and communities. In all those ways, he embodied an ideal activism, one from which 21st century America still has a great deal to learn.

Featured image: The Liberator (Wikimedia Commons)

Considering History: Native Americans, Sovereignty, and the Mashpee Revolt

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

While not as prominent nor as straightforward as the growing movement to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day, recent years have seen a complementary challenge to how we think about Thanksgiving. For instance, native historian and public scholar Philip Deloria recently wrote a bracing article “The Invention of Thanksgiving,” for The New Yorker, where he discusses both the historical oppression at the time of the so-called “First Thanksgiving” and the ways in which our subsequent collective constructions of that event have too often amplified that oppression.

For last year’s Thanksgiving column, I offered one way to challenge those constructions without discarding the cherished traditions of the holiday: by remembering a figure like Tisquantum and all the histories to which he connects.

Recently, narratives about Thanksgiving have shifted away from the history of the holiday, and toward the broader concepts of gratitude and appreciation for blessings in our lives. And seen through that lens of gratitude, we can remember another lesser-known event that established one of America’s most enduring and inspirational communities, the Mashpee Revolt of 1833.

The Native American community in Mashpee, Massachusetts included the Wampanoag tribe, one of the first to encounter English arrivals in New England. Over the course of the 17th century (despite the six-point peace treaty negotiated by Chief Massasoit with the help of Tisquantum) they suffered some of the most destructive effects of that contact. While that history includes overtly violent events such as the mid-1670s King Philip’s War, it also featured a consistent thread of English settlers taking land and resources from Wampanoag villages. The Wampanoag men and women who endured these incursions and removals, and who survived the epidemics that the European arrivals brought with them, began to gather in “Indian town,” a community that sprang up in the Cape Cod area known as Mashpee.

Yet if the town was created in part out of tragic necessity, it also represented a self-determined and inclusive model for Native American community in post-contact America. Native Americans from other local tribes began to move into the area as well, and in 1665 two Wampanoag chiefs formally deeded the land to this burgeoning, multi-cultural native community. The deed, filed in Plymouth Court, noted that Mashpee would belong to these indigenous inhabitants “forever; so not to be given, sold, or alienated from them by anyone without all their consents thereunto.” The town and community continued to expand and thrive for the next century, and on June 14th, 1763 the Massachusetts General Court officially incorporated Mashpee as a “plantation,” the colony’s designation for a civic space belonging to its local residents. Yet with this recognition came a step backwards in the community’s development: the patronizing appointment of white “overseers.”

Over the next half century, neighboring white settlers took advantage of that status — and of the general atmosphere of exclusion that would culminate in the 1830 Indian Removal Act — to pilfer resources from Mashpee. Firewood was frequently stolen from the community’s forests, and fish and shellfish from its Cape Cod waters. Not only did the white overseers not challenge nor stop these behaviors, but they actively encouraged them, allowing neighboring white farmers to lease grazing land for their livestock and (per the Mashpee community’s frequent and unanswered pleas to the state legislature) keeping the money for themselves. And, in the early 1830s, when a Native American preacher known as “Blind Joe” Amos sought to lead a congregation of those in the town who had converted to Christianity, the state’s appointed white minister barred him from using the meetinghouse, forcing him to conduct his services outside.

At the same time these injustices were unfolding, an important new presence came to Mashpee: a passionate and eloquent itinerant Methodist minister named William Apess. Apess had spent the last few years traveling throughout New England, preaching to indigenous communities, and speaking and writing about Native American history, identity, religion, and community, blending both Christian and traditional spirituality and stories (such as those of his Pequot ancestors and of King Philip, to whom he claimed relation on his mother’s side) with political and legal arguments. He had heard about the issues facing Mashpee, both religious and territorial, and in early 1833 traveled to the community to see what he could contribute on each of those levels.

Ready to challenge their intrusive neighbors and ineffective overseers, and encouraged by this activist visitor to pursue self-governance, the Mashpee elected a 12-man council. Three of those councilmen, Israel Amos (a relative of Blind Joe’s), Isaac Coombs, and Ezra Attaquin, would later write, in a letter to the state legislature in support of Apess, that “the Great Spirit who is the friend of the Indian as well as of the white man, has raised up among you a brother of our own and has sent him to us that he might show us all the secret contrivances of the pale faces to deceive and defraud us.” The council and tribe had, they added, “all the confidence in him that we can put in any man,” and inspired by that confidence, the council worked with Apess to draft a formal document of protest, a petition sent “to the Governor & Council of the State of Massachusetts” on May 21st, 1833.

That petition, signed by 108 men and women from the community and collectively authored “on behalf of the Mashpee Tribe” and “in the voice of one man,” had two practical purposes: to lodge a series of protests about the abuses perpetrated by both white neighbors and state overseers; and to set a date of July 1st, 1833, as a line of demarcation, after which the tribe would “not permit any white man to come upon our plantation to cut or carry off wood or hay or any other article.” But along with those resolutions was a more philosophical and inclusive statement: “That we as a Tribe will rule ourselves, and have the right to do so for all men are born free and Equal, says the Constitution of the country.”

Both the neighboring and official white communities responded to this document with hostility. On July 1st, the very date set by the tribe as the start of formal resistance, two men from the nearby town of Barnstable arrived in Mashpee to test the tribe’s will by cutting and stealing wood. When tribal residents unloaded their wagon and forced the men to leave, the state responded by siding with the intruders. Apess and a few other men were arrested, charged with “riot, assault, and trespass,” and sentenced to thirty days in jail. Massachusetts Governor Levi Lincoln threatened to muster the state militia if the tribe continued its resistance, and the white press, perhaps angling for military intervention such as President Andrew Jackson’s use of the army to enforce the Removal Act in the Southeast, began to call the unfolding crisis the “Woodlot War.”

The Mashpee tribe did not meet this provocation with violence, but neither did they back down from their protests and demands for equality. As Apess would later write in his book Indian Nullification of the Unconstitutional Laws of Massachusetts, Relative to the Mashpee Tribe; or, The Pretended Riot Explained (1835), “All that the Indians want in Mashpee is to enjoy their rights without molestation. They have hurt or harmed no one. They have only been searching out their rights, and in so doing, exposed and uncovered, have thrown aside the mantle of deception, that honest men might behold and see for themselves their wrongs.” That sentence’s final clause is particularly important, for as Apess argues in his book’s conclusion, the success of the Mashpee Revolt (as it would come to be known) depended on garnering more sympathetic and inclusive responses from powerful potential allies in the state: “it was necessary, for their future welfare, as it depends in no small degree upon the good opinion of their white brethren, to state the real truth of the case, which could not be done in gentle terms.”

Fortunately, the petition and protests, as well as the continued activism of Apess and others, did find sympathetic audiences. A first step was securing a friendly journalistic voice to counter the exclusionary press narratives, and Apess found one in Benjamin Hallett, journalist, lawyer, and rising star in the state’s Anti-Masonic Party. His advocacy helped convince the state legislature to send a delegation in late 1833 to investigate conditions in Mashpee, and they produced a lengthy report indicting the white overseers and supporting the tribe’s positions. On January 21st, 1834, Apess and other tribal leaders journeyed to Boston to address a special evening session of the legislature, and four days later the abolitionist activist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison took up the cause in an editorial in his newspaper The Liberator.

On March 31st, 1834, the tribe won a crucial victory: the legislature voted to abolish the community’s white guardianship and turn Mashpee into a “district,” giving its residents the official power to elect their own government and manage their own affairs. This step note only granted the Mashpee tribe the sovereignty for which it had been fighting but also recognized it as a community much like other self-governing Massachusetts towns; indeed, Mashpee would be incorporated as a town in 1870, and remains one to this day. Over the last few years, however, Mashpee has once again been threatened, this time by Trump administration policies that seek to keep the tribe from building a casino (and as part of a broader attack on Native American tribal sovereignty). As with so many inspiring American histories in 2019, remembering and appreciating this one means also fighting for its present rights and future existence. I can think of no more apt way to celebrate Thanksgiving.

Featured image: King (Metacomet) Philip, Sachem of the Wampanoags, 1676, full length, standing at treaty table (Library of Congress)