A Historic Birthday for America’s Peanut Farmer President

Today marks the first time a U.S. president has ever turned 95 years old.

James Earl Carter, when he made his first run for the presidency in 1976, surprised many in the Democratic party by winning some key races in the early primaries. His “outsider” politics and small-town charm made Carter a refreshing candidate to many in a tumultuous political decade. After he lost his second bid for the White House, he and his wife Rosalynn went back to their peanut business in Plains, Georgia, where they still live today.

In a 1976 television ad, Carter emphasized his everyman image while describing his hope for a country recently rocked by scandal and corruption: “a president who feels your pain and who shares your dreams.” Images of pastoral American landscapes flashed across the screen in tandem with smiling American faces: a man in a hardhat, an African-American couple, a redheaded kid. Carter’s popularity among minorities and poor voters reflected his promises to bring honesty and competence back to national governance. His rural, agricultural background was an asset in so-called B and C counties (categorized at the time as those lacking a city with 50,000 or more people).

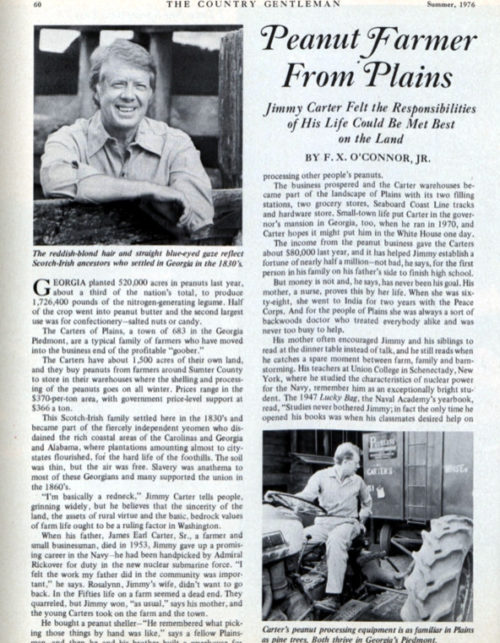

Country Gentleman covered Carter and his peanut business in the summer of 1976. The Georgia governor’s candidacy led the magazine to proclaim, “The white-suited, string-tied, Panama-hatted stentorian orator of yesterday has vanished, and people like Carter are taking his place.”

Going back to the land was a widespread movement at the time of Carter’s run, but he and Rosalynn had made the leap years before it became popular. In 1953, while he was in the Navy, Carter’s father died and left behind the peanut farm in Plains. Carter — and a reluctant Rosalynn — took it up and built it into a full-service peanut processing plant. They made it profitable, too, and Carter gained trust in his local religious and civic communities with a longstanding reputation for trustworthiness.

Last year, Carter advisor Stuart Eizenstat wrote about the peanut farmer’s years in the White House, opining that many had unfairly assessed Carter’s presidency to be ineffectual. Carter’s unwavering governance was grounded on an almost anti-political ethic, as Eizenstat argues, and this made way for more inconspicuous policy wins — “such as energy, the Panama Canal, and the Middle East.” The president’s commitment to winning back Americans’ trust in the Oval Office (“I will never lie to you.”) seems a particularly appealing objective in the current age of post-truth politics.

After Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter left the White House, they were a million dollars in debt. Their peanut business lost money while it was held in a blind trust during his presidency, and they had to sell. Carter wrote dozens of books, though, and the ex-president is known for his thrifty lifestyle. The couple still lives in their $167,000 ranch house in Plains. They fly commercial and requested the smallest budget from the federal government in 2019 of all ex-presidents. Carter even buys his clothes at the Dollar General store, according to Rolling Stone.

Carter’s post-presidency has been characterized by tireless humanitarian work and simple living, lending credence to his real-deal reputation. To send President Carter a birthday message on this historic day, you can visit the Carter Center’s website.

Featured image: Alamy

The 5 Most Memorable State of the Union Addresses

Ever since George Washington, the American president has given an annual message every year. It’s how he complies with the Constitution’s order that “from time to time,” he report on the state of the union and make “necessary and expedient” recommendations.

Originally delivered orally by the president, the annual report was submitted to Congress as a written document between 1800 and 1913. But President Wilson revived the tradition of personally reading the address.

Since then, there have been only few years when the President sent a written report.

This year, millions will watch Donald Trump’s address to hear what he has to say. If this address is like most, he will talk in broad terms of policy and propose laws that support his priorities.

Few, if any of those laws will make it out of committee. Out of 94 spoken addresses, only a handful made a lasting impression on America or the world.

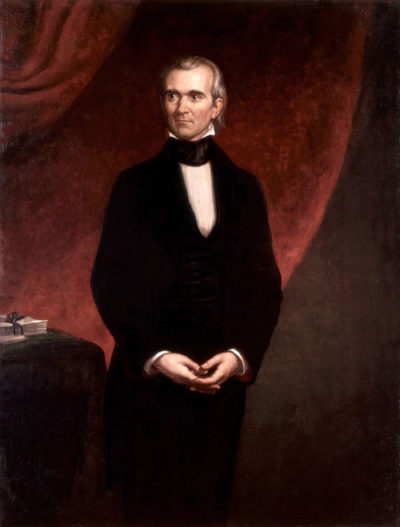

James Polk

President Polk’s fourth state of the union address in 1848 launched a massive migration westward. In ten years, the white population of California rose from 80 to 300,000 — because the president reported that the rumors of gold in California were true.

Polk said, “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.”

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 address expressed the principles for which northern men would fight and die over the next three years. It also set the bar for state of the union address for what is arguably the best prose ever written by a president:

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation…In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

Franklin Roosevelt

In 1942, President Roosevelt put the country’s wartime goals into words. Achieving these goals would be the full time job for 16 million Americans over the next three years. The U.S., Roosevelt said, was fighting to achieve four freedoms— not just the U.S. but for the entire world.

“Freedom of speech and expression…

“Freedom of every person to worship God in his own way…

“Freedom from want, which… means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants…

“Freedom from fear… a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point … that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.”

Lyndon Johnson

Few addresses touched as many American lives as the 1964 message from Lyndon Johnson, which launched his a highly ambitious “unconditional war on poverty.”

“Our aim,” he said, “is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”

In the months that followed, he pushed legislation that would expand the government’s role in civil rights, education, and health care. It would produce the Office of Economic Opportunity, Job Corps, VISTA, food stamp program, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton stunned Congress in his 1996 address when he announced “the era of big government is over.” It was a startling turn-around for the head of a party that had long supported increased government programs to address social ills. In the coming months, Clinton introduced spending cuts that pared back programs and enabled him to announce, in his 1998 address, that the government had balanced its books and was expecting a surplus. “What should we do with this projected surplus? I have a simple four-word answer: Save Social Security first.”

We should also mention, in passing, a few addresses that may not have directly affected Americans’ lives, but contained lines that proved ironic or all too true.

George W. Bush, in his 2003 address, identified Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as an “axis of evil” whose regimes were seeking “weapons of mass destruction.” It was a claim that would come back to haunt the administration when no such weapons were found in Iraq.

In 1974, Richard Nixon was under pressure from the Congressional Committee looking into the Watergate break-in. He told America, “I believe the time has come to bring that investigation and other investigations of this matter to an end. One year of Watergate is enough.” But it wasn’t enough for Congress. Seven months later, Nixon resigned.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford broke with the long tradition of presidents declaring the state of the union was strong. Ford had the courage to honestly say, “I want to speak very bluntly. I’ve got bad news, and I don’t expect much, if any, applause… the state of the Union is not good: Millions of Americans are out of work. Recession and inflation are eroding the money of millions more. Prices are too high, and sales are too slow. This year’s Federal deficit will be about $30 billion; next year’s probably $45 billion. The national debt will rise to over $500 billion.” It was the opening to an address that presented measures he felt would “rebuild our political and economic strength.”

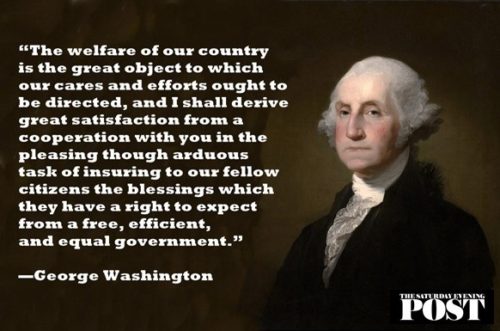

Finally, we should consider George Washington’s report from 1790, which some consider to be the ideal address. It was a concise: a thousand words long. (The longest address was given by President Clinton in 1995: 9,190 words. President Carter’s 1981 report, submitted in writing, exceeded 33,000 words.)

It offered practical advice, was short on flowery language or self praise, and concluded with this essential message that should inspire every president’s address to Congress:

“The welfare of our country is the great object to which our cares and efforts ought to be directed, and I shall derive great satisfaction from a cooperation with you in the pleasing though arduous task of insuring to our fellow citizens the blessings which they have a right to expect from a free, efficient, and equal government.”

Shortest Stays in the White House

Yesterday, Communications-Director-in-Waiting Anthony Scaramucci resigned before he had officially assumed his post, so it can’t be said that he had the shortest tenure in the current White House — because he didn’t have any tenure. General Michael Flynn, who announced in February that he was leaving his position of National Security Advisor, had served just 24 days.

Death and Illness

Two dozen days is a pretty short stay for a Cabinet member, but he does not hold the record for brevity of tenure. That honor goes to Thomas W. Gilmer, a Virginia congressman who was appointed Secretary of the Navy by President John Tyler. He assumed the office on February 19, 1844, and died 10 days later.

Death was also the culprit in the short term of office for President William Henry Harrison, who is still remembered for three things: winning the Battle of Tippecanoe, delivering the longest inaugural address, and dying 32 days after becoming president. His unexpected death is now attributed to typhoid, a common ailment at the time in Washington, which hadn’t yet engineered a proper system for disposing of sewage.

And while Elihu Washburne didn’t die while serving as Secretary of State under Ulysses S. Grant, he became ill after his appointment on March 5, 1869, and resigned 11 days later.

A few of our vice presidents had short terms because the president under whom they served died unexpectedly. This was the case for John Tyler, who succeeded William Henry Harrison after his death from typhoid, making Tyler’s vice presidency the shortest on record, at 33 days. Andrew Johnson served as VP for only 43 days and became president after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

Out of Time

Luckily, death was not a typical reason for a short period of service. More commonly, a president’s term would end and his staff would be replaced. When President James Buchanan left office, so did his recently appointed postmaster general, Horatio King, who served just 21 days.

Similarly, the first agriculture secretary served just 20 days. Previously the Commissioner of Agriculture, Norman J. Colman had pushed President Grover Cleveland to create a Department of Agriculture. He was named its first secretary on February 15, 1889. Unfortunately, President Cleveland left office 20 days later, and so did Colman.

And when President Lyndon Johnson left office, so did Treasury Secretary Joseph Barr, after only 21 days in the position. Because of his short tenure, Barr’s signature appeared only on the one-dollar bill.

Politics and Drama

While these resignations occurred during peaceful transitions, several were the result of White House tensions. Edwin M. Stanton briefly served as Attorney General for the last days of President Buchanan’s term. Stanton perceived that Buchanan was too soft in his treatment of the South before the Civil War and resigned after 76 days. But he was recalled by President Lincoln to become Secretary of War, a post he held for six years.

More recently, Attorney General Elliot Richardson resigned on October 20, 1973, rather than comply with President Nixon’s orders to fire the special prosecutor looking into the Watergate scandal. He had lasted 150 days.

Donald Trump’s former chief of staff, Reince Preibus, served 189 days — the shortest time anyone has served in this position. Preibus resigned, but many believe he was pushed out after a stormy six months in the White House.

Michael Dubke accepted the position of White House Communications Director in March 2017. Anticipating another staff shake-up, he submitted his resignation to President Trump 85 days later. He had replaced Sean Spicer — and was succeeded by him as well. Spicer served in the White House for 183 days as Communications Director, press secretary, or some combination of the two, before resigning in July rather than working with Scaramucci.

Not all short terms are accompanied by death or drama: Friends talked Congressman Thomas McKennan into becoming Interior Secretary for President Fillmore. He didn’t think he would like the job. After 29 days, he was certain, and he left.

Shortest Stays in the White House

| Person | Position | President Served | Tenure | Reason for Leaving |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas W. Gilmer | Secretary of the Navy | John Tyler | 10 days | death |

| Elihu Washburne | Secretary of State | Ulysses S. Grant | 11 days | illness/resignation |

| Norman J. Colman | Secretary of Agriculture | Grover Cleveland | 20 days | end of the president’s term |

| Horatio King | Postmaster General | James Buchanan | 21 days | end of the president’s term |

| Michael Flynn | National Security Advisor | Donald Trump | 24 days | resignation |

| Thomas McKennan | Secretary of the Interior | Millard Fillmore | 29 days | resignation |

| Joseph Barr | Secretary of the Treasury | Lyndon Johnson | 31 days | resignation at end of the president’s term |

| William Henry Harrison | President | William Henry Harrison | 32 days | death (typhoid) |

| John Tyler | Vice President | William Henry Harrison | 33 days | became president |

| Robert C. Wood | Secretary of Housing and Urban Development | Lyndon Johnson | 34 days | end of the president’s term |

| Robert Bacon | Secretary of State | Theodore Roosevelt | 38 days | end of the president’s term |

| Lawrence Eagleburger | Secretary of State | George H.W. Bush | 43 days | end of the president’s term |

| Andrew Johnson | Vice President | Abraham Lincoln | 43 days | became president |

| Jonathan Daniels | Press Secretary | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 45 days | left after FDR’s death |

| Edwin M. Stanton | Attorney General | James Buchanan | 76 days | resignation |

| Michael Dubke | Communications Director | Donald Trump | 85 days | resignation |

| Elliot Richardson | Attorney General | Richard Nixon | 150 days | resignation |

| Sean Spicer | Communications Director/press secretary | Donald Trump | 183 days | resignation |

| Reince Preibus | Chief of Staff | Donald Trump | 189 days | resignation |

Featured image: Shutterstock

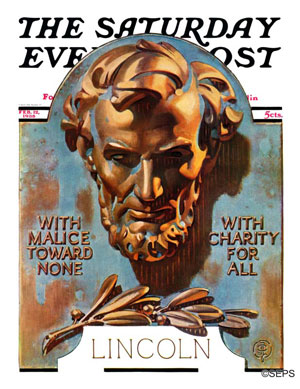

Cover Gallery: Presidents

The Saturday Evening Post has featured many U.S. presidents on its cover in its nearly 200-year history. Here is a gallery of the men who have helped shape our nation.

By Karl Kleinschmidt

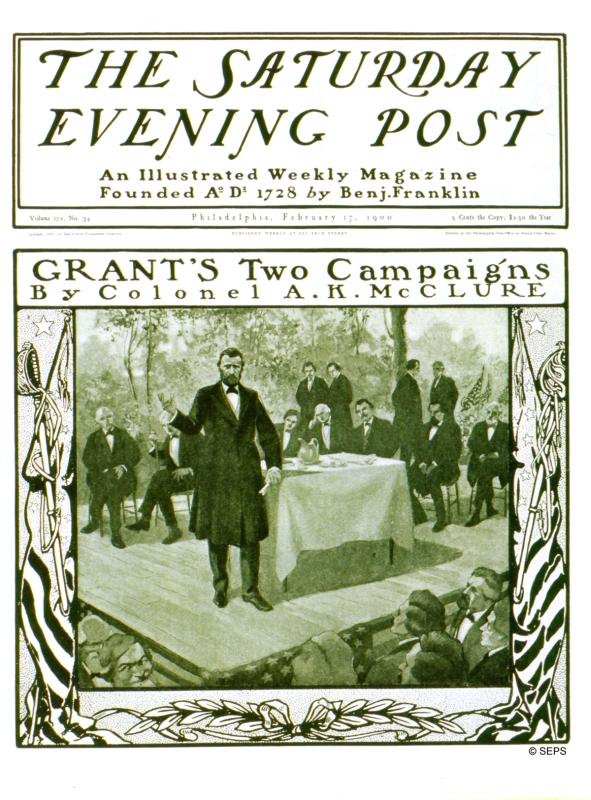

February 17, 1900

Fifteen years after his death and 23 years after leaving office, Grant appeared on the cover of the Post, in one of a series of articles by Colonel A. K. McClure on “How We Make Presidents.” Grant oversaw the elimination of Confederate nationalism and slavery, protected African-American citizenship, and supported industrial expansion.

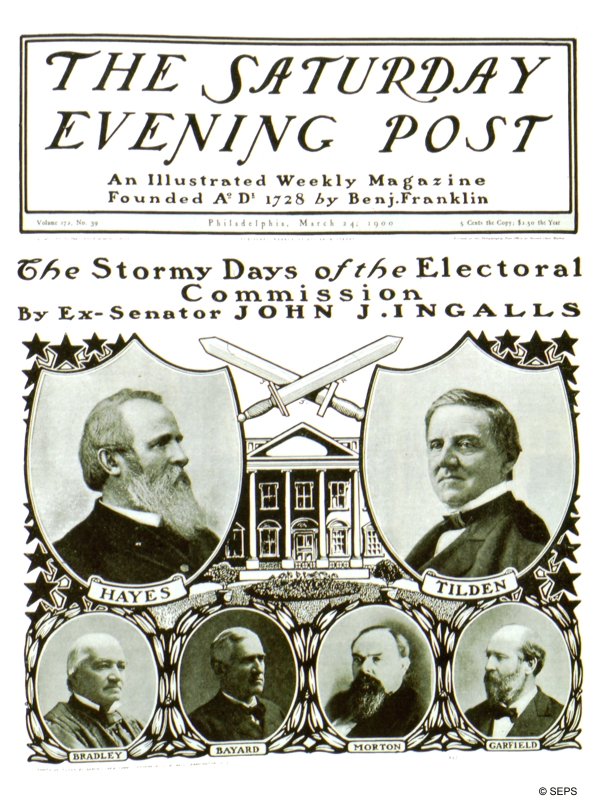

By Sarony & Bell

March 24, 1900

The election of 1876 was one of the most contentious in U. S. history. It was one of only five elections in which the person who won the most popular votes did not win the election. At one point, Tilden had 19 more electoral votes than Hayes. But a deal was brokered in which 20 disputed electoral votes were awarded to Hayes in exchange for withdrawal of federal troops from the South, putting Hayes in the White House by one vote.

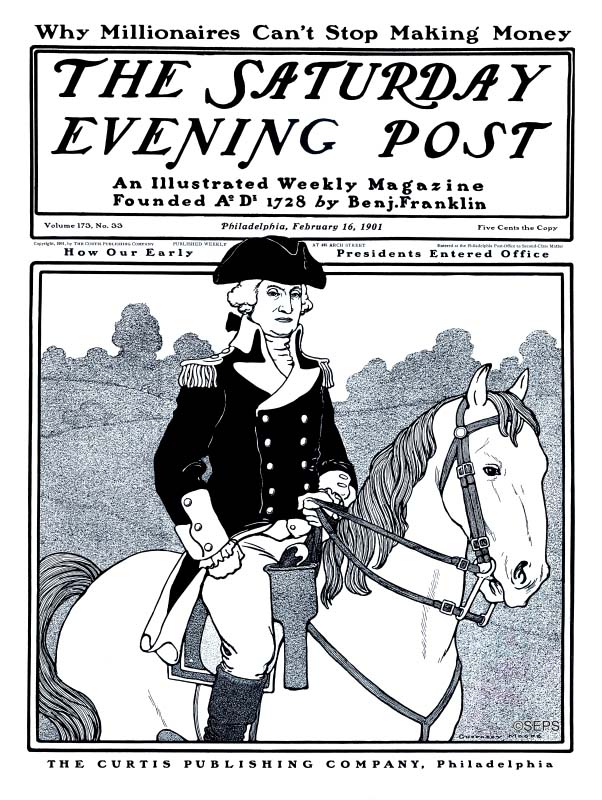

By Guernsey Moore

February 16, 1901

As he was handing over the reins of the presidency to his successor, John Adams, Washington wrote, “I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy.”

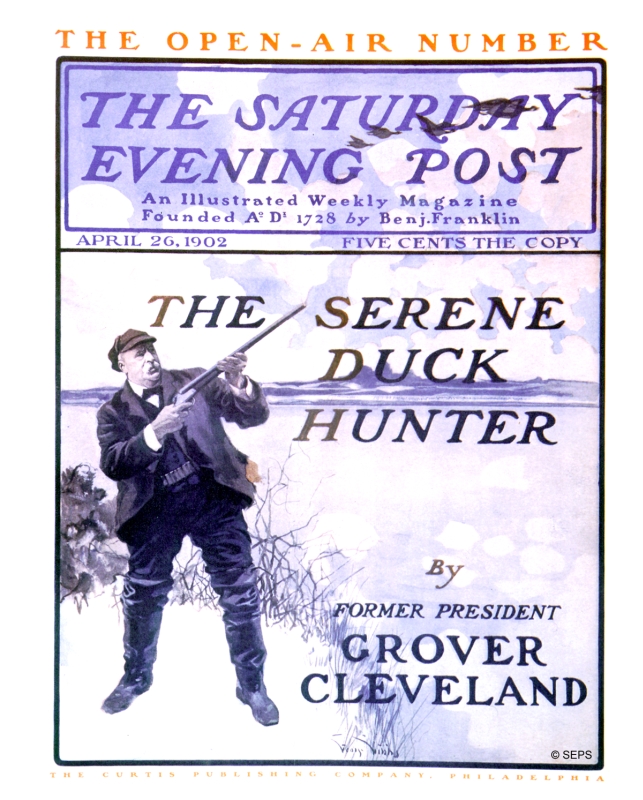

By George Gibbs

April 26, 1902

Grover Cleveland was only U. S. President to serve two non-consecutive terms in office. He appeared on seven Saturday Evening Post covers and wrote several articles for the magazine on hunting, fishing, and the plight of democracy (not necessarily in that order of importance). He is remembered for being the only president to marry while in the White House, and for his deathless statement, “What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something?”

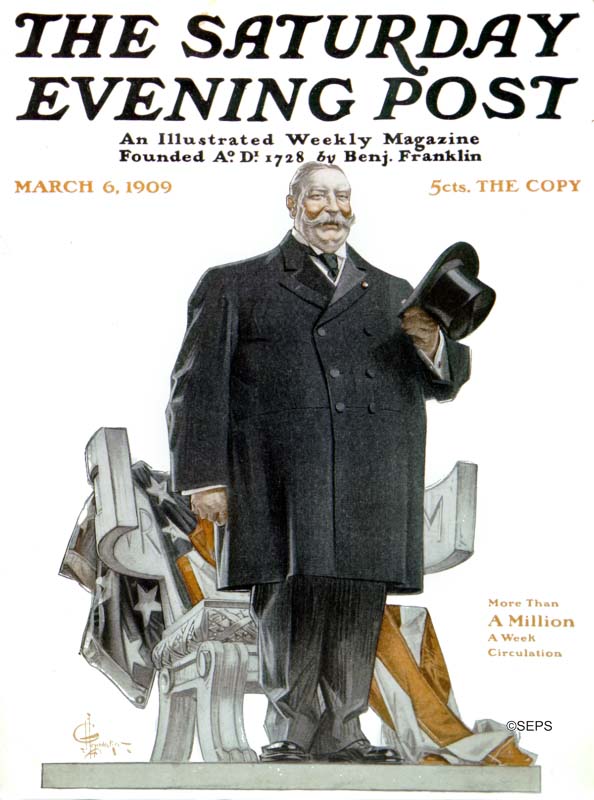

By J. C. Leyendecker

March 6, 1909

An article in this issue of the Post proclaimed Taft to be “the heaviest President, the most traveled President, the best-natured President and the first golf player to occupy the White House.” He was among the most amiable and least ambitious men to be elected to the office. He continued most of the policies of his predecessor and friend, Teddy Roosevelt, but the two became estranged and ran against each other in 1912.

All his life, Taft tried in vain to reduce his weight. He reached 355 pounds while he served unhappily as president. He was also the only president to also serve as a justice on the Supreme Court, where he was far happier.

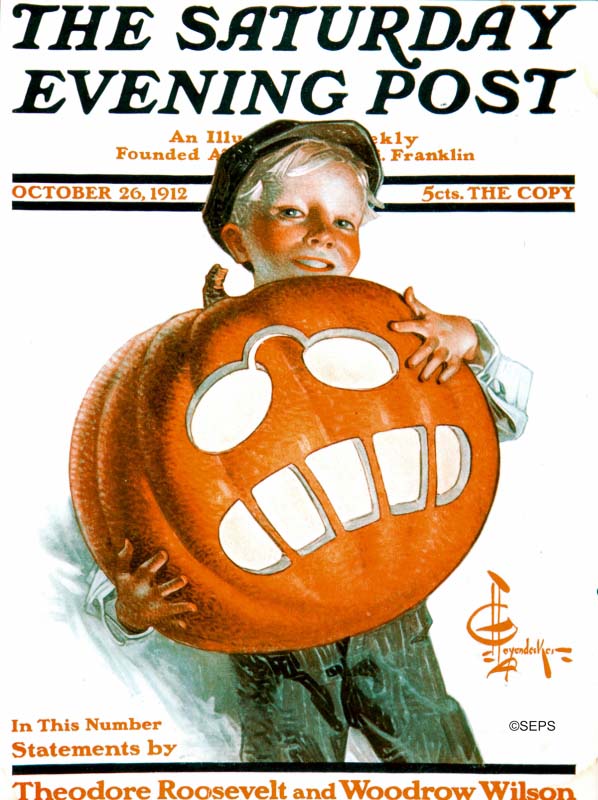

By J. C. Leyendecker

October 26, 1912

The Post was fascinated and charmed by Theodore Roosevelt, an energetic, progressive, young president who interrupted the long line of serious old men in the White House. Post editorials applauded his campaigns against “malefactors of great wealth” and his enthusiasm for making the U.S. a global power. Coming to the presidency in 1901 after President McKinley was shot, he was elected to a full term in 1904. He stepped aside in 1908 to let his friend, William H. Taft, successfully run for office. But in 1912, when this boy carved his pumpkin with TR’s toothy grimace and pince nez glasses, he was trying unsuccessfully for another term.

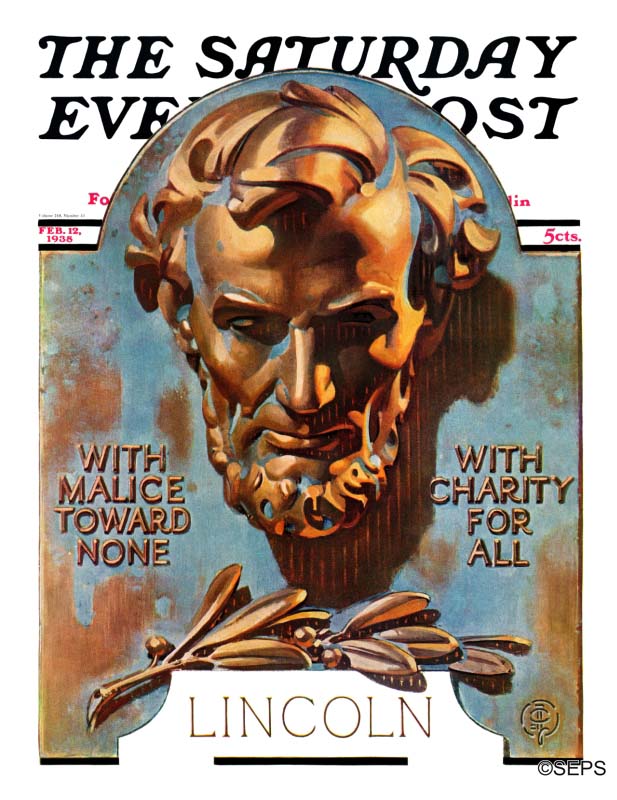

By J. C. Leyendecker

February 12, 1938

In 1862, with the country at the end of a Civil War, Lincoln called on Americans to face the challenges ahead without looking backward. He also reminded members of Congress that they would all be remembered for what they did in those perilous times:

“The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.”

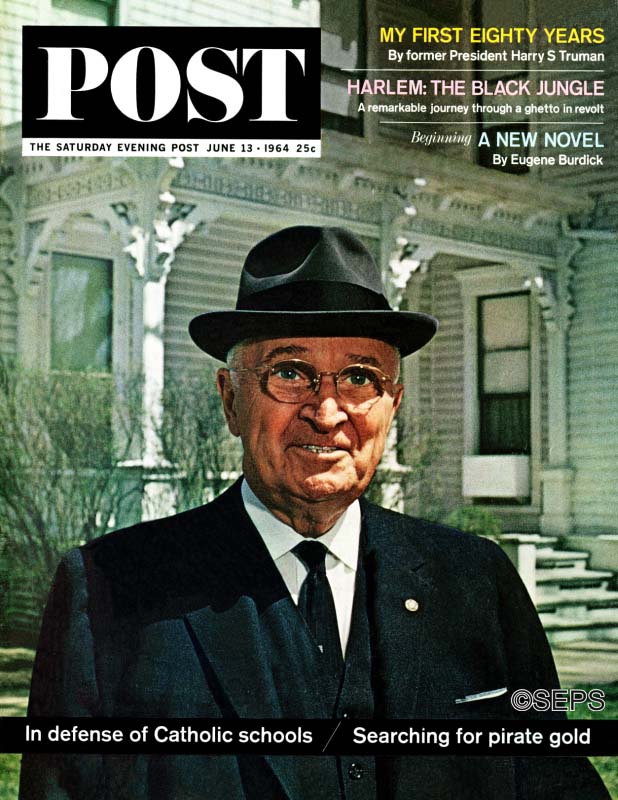

By John Launois

June 13, 1964

This photograph of former President Truman was taken in front of his Independence, Missouri home. In an article that Truman wrote for the Post, the 80-year-old looked back over his controversial career and explained the principles that guided him in making the most difficult decisions of his Administration — including the “firing” of Douglas MacArthur.

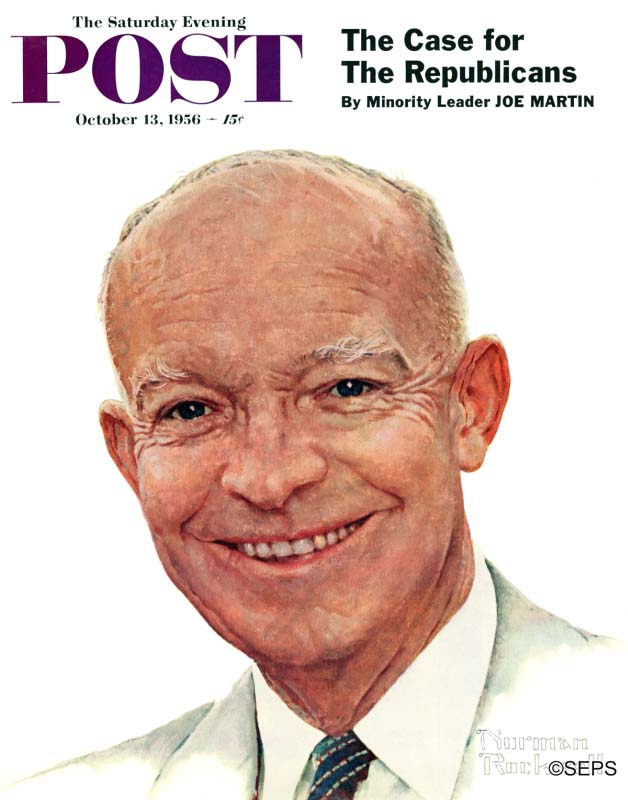

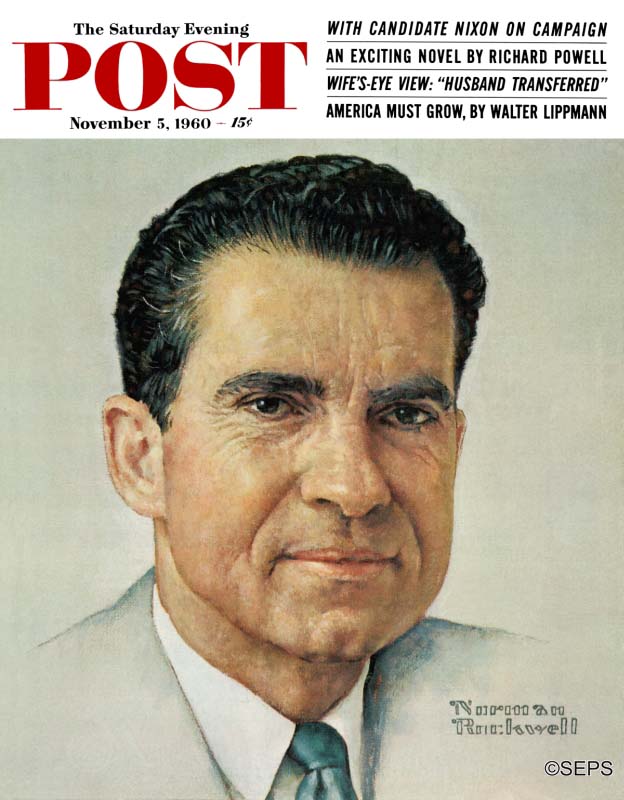

By Norman Rockwell

October 13, 1956

The Post hadn’t featured a sitting president on its cover since Taft’s appearance in 1909. A popular president, Eisenhower authorized the establishment of NASA, invoked executive privilege to help end McCarthyism, expanded social security, launched the interstate highway system, and established the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency which led to the development of computer networking and graphical user interfaces.

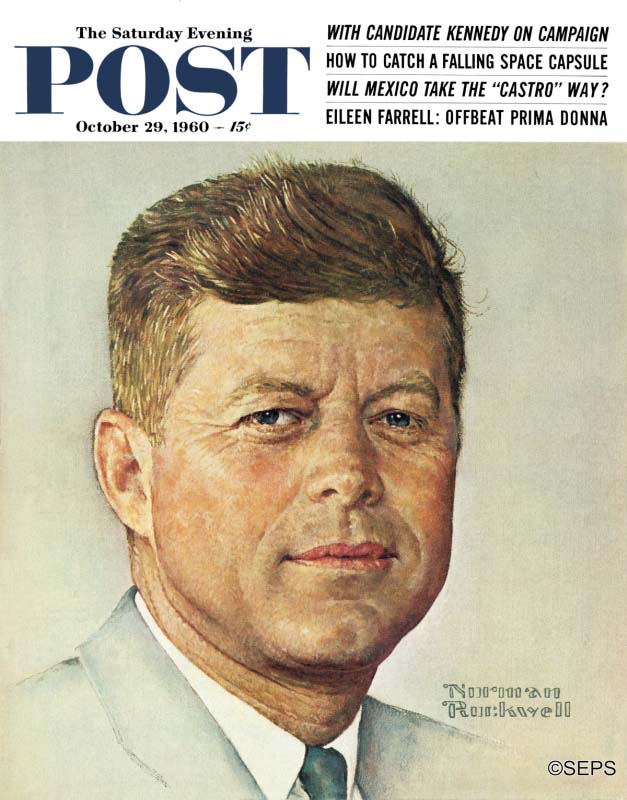

By Norman Rockwell

October 29, 1960

Among his many better known accomplishments, Kennedy also won a Pulitzer Prize (for “Profiles in Courage”), was awarded a Purple Heart, and donated his salary to charity. He represented the new generation of politicians: he was young, good-looking, smart, and funny, and drew international admiration. Kennedy spoke of idealism at a time when the country wanted to move on to new horizons, but his aggressive stance against communism brought the country close to one war and involved it in another, in Vietnam.

This Rockwell portrait appeared a second time when the Post ran its memorial issue after Kennedy’s assassination.

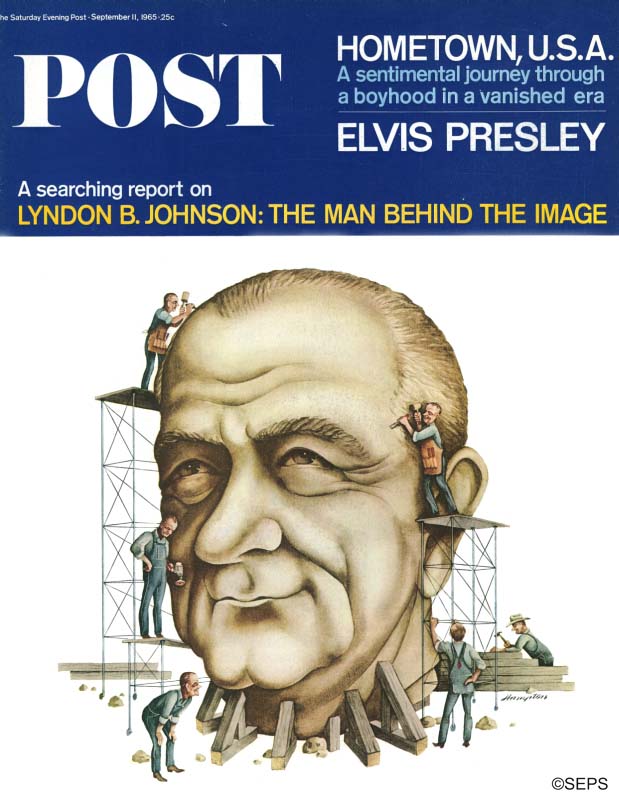

By Blake Hampton

September 11, 1965

President Johnson was a politician’s politician, and he was a paradox. He was cynical and calculating enough to be a powerful force in Washington, but also a champion of the poor and the man who launched a “War on Poverty. Johnson signed several civil rights bills that banned racial discrimination in public facilities, interstate commerce, the workplace, and housing. He signed the Voting Rights Act and the Immigration and Nationality Act into law. When he came to the White House after Kennedy’s assassination, he enjoyed a long honeymoon period with the press. But he lost the support of the media, and many Americans, with his determination to continue sending American soldiers to Vietnam.

By Norman Rockwell

November 5, 1960

President Nixon is best remembered for the Watergate scandal and his subsequent resignation, but he also opened diplomatic relations with China, initiated détente with the Soviet Union, and established the Environmental Protection Agency. He ended U.S. involvement in Vietnam, and supported the Equal Rights Amendment, affirmative action, and the food stamp program. It was ironic that a man who rose in politics through his anti-communist stance made such significant progress with the communist governments of Russia and China.

Rockwell painted this portrait of candidate Nixon nine years before Nixon won the presidency.

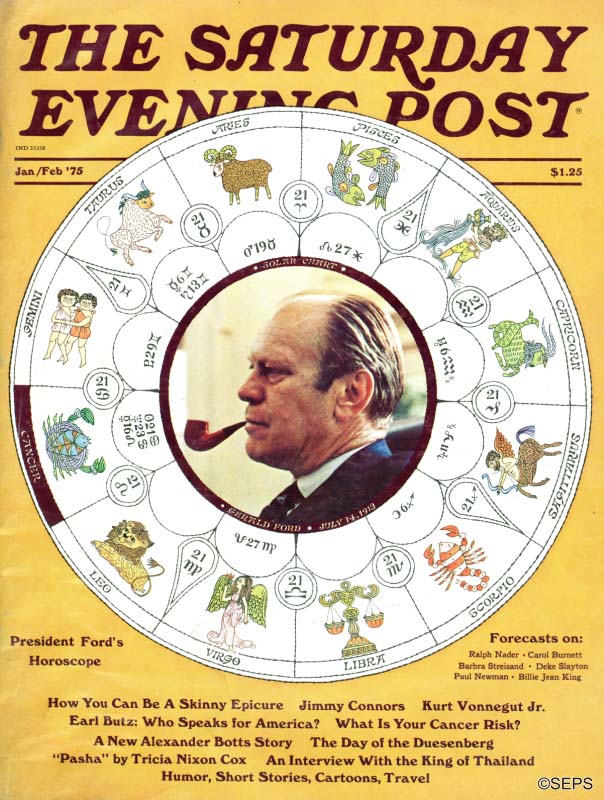

By J. Moore

January 1, 1975

In this feature in the Post, “astrologer to the stars” Carroll Righter analyzed President Ford’s astrological profile, terming him a Moonchild. Ford has the distinction of being the only person to have served as both Vice President and President of the United States without being elected to either office. It has not been determined if the alignment of the stars or planets was a factor.

Entering the White House abruptly when President Nixon resigned, he drew broad support by pardoning the men who’d avoided serving in Vietnam by illegally dodging the draft. But much of his popularity melted away when he also pardoned Nixon, sparing the nation a long, rancorous, divisive spectacle of a trial.

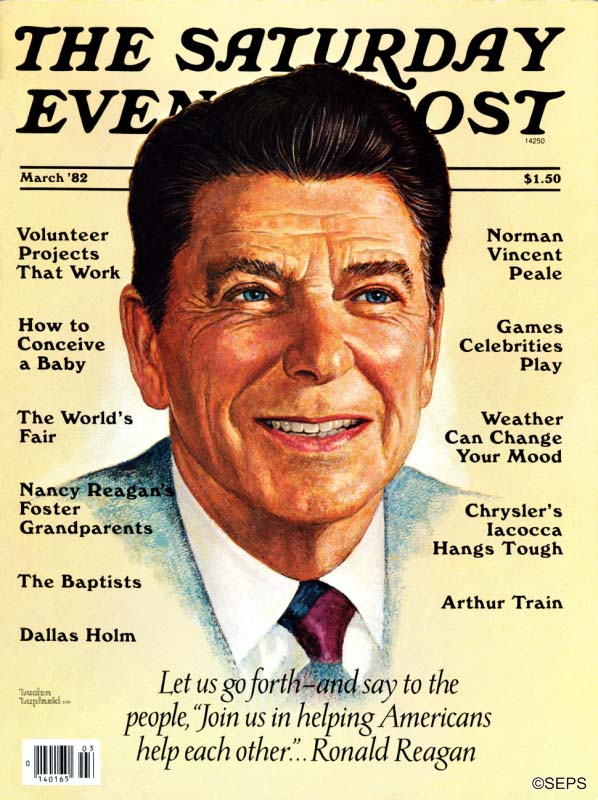

By Lucian Lupinski

March 1, 1982

Once a Democrat, Reagan switched to the Republican party as his views became more conservative. As president, he supported Afghan rebels opposing Russia’s invasion of their land and pushed for a space-based missile system to protect America from a nuclear attack. In the end, though, he was the president whose policies and tactful diplomacy with Russian leaders would end the Cold War.

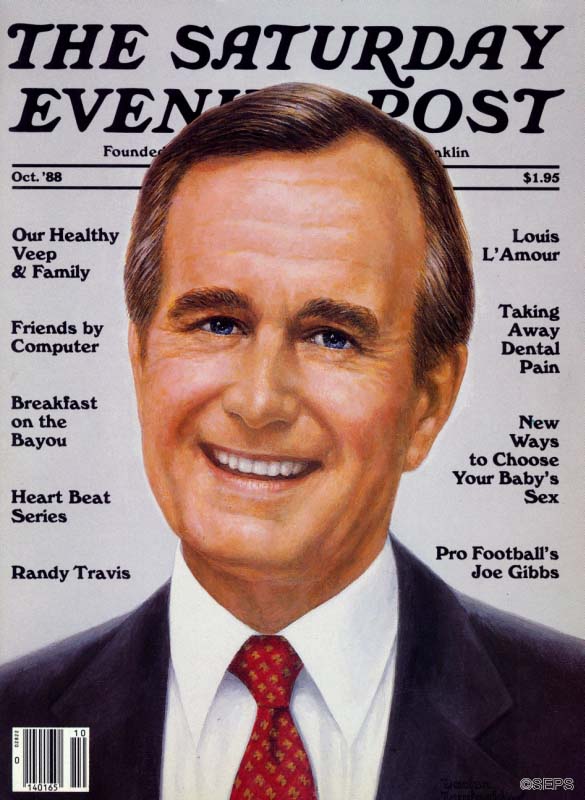

By Lucian Lupinski

October 1, 1988

George H. W. Bush appeared on the Post cover when he was still vice president, but was poised to win the presidential election, held a month later. He is the oldest living former president and vice president.

Bush continued many of Reagan’s policies, but he bridled when journalists compared him unfavorably to the charismatic Reagan. He was portrayed by some as being weak, sheltered, and a wimp. Yet it was Bush, not Reagan, who served in World War II and survived being shot down as a Navy pilot. His single term was noted for his authorization of the military overthrow of a corrupt dictator in Panama and the smashing of Iraq’s force in Kuwait though Operation Desert Storm.

Fighting the Fear of Presidential Assassination

A presidential assassination is a tragedy that burns itself into the memories of a generation. Most Americans who were alive in 1963 can tell you exactly where they were when they heard about John F. Kennedy’s assassination. And it was the same for Lincoln’s death: In the 1890s, federal interviewers found that elderly citizens could still remember exactly what they were doing when they heard the news of Lincoln’s assassination.

The specter of presidential assassination lingers in the back of the American mind, but a recent comment about “second-amendment people” has brought it to the fore. Many Americans are now pondering the question of how far we should go — or, put another way, what we are willing to give up — to protect the life of our president. The following article provides one perspective from over a century ago.

President William McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, while making a public appearance in Buffalo, New York. He died of gangrene on September 14. America’s citizens, concerned for the safety and protection of their chief executive officer, were weighing the question of presidential safety versus public access. Some even advocated the complete removal of the president from public venues.

While America was still recovering from this disaster — while McKinley’s assassin, Leon Czolgosz, was still waiting in prison for his execution day — McKinley’s predecessor, Grover Cleveland, offered Post readers his viewpoint on why it’s so important for the public to have access to the president, more important even than the threat of assassination.

The Safety of the President

By Grover Cleveland

Excerpted from an article originally published on October 5, 1901

It is suggested that the safety of the president can be much increased by curtailing his accessibility to the public. It is even said that the custom which has always permitted the people large latitude in meeting and greeting their chief executive, by taking him by the hand, is absurdly dangerous.

A radical diminution of the popular enjoyment of those privileges would be much more difficult of accomplishment than at first blush is apparent. The relations between all the decent people of the land and the president are very close. On the part of the people this situation is the outgrowth of their feeling that they have a more direct proprietary interest in the presidential office than in any other instrumentality of their government. They have determined by their united and simultaneous suffrages who the president shall be. In his high office they regard him as the representative of their sovereignty and self-government; and, as the administrator of laws made for their welfare and advantage, they look upon him as their near friend — alive to their needs and anxious for their prosperity and happiness. Closely allied to these sentiments and perhaps directly resulting from them there is an immensely strong band of attachment between all good citizens and their president which, though difficult to define, is nevertheless unmistakably real and distinctively American. In the minds of all law-abiding people, excepting an insignificant minority whose love of country is selfish or who make party scheming an occupation, this attachment overreaches party affiliations and crowds out of memory the exciting incidents of party strife. It may be said to rest upon a feeling of sincere and generous goodfellowship or comradeship which includes the idea that, though the president has been clothed with high honor by his fellow-countrymen, he is still one of the people, that he still needs their support and approbation, and that he is still in sympathy with them in every condition of their daily life.

This attachment and affection of our plain and honest people for their president is not only manifested by their desire to see, hear, and greet him, but these kindly sentiments are stimulated and strengthened by every indulgence of this desire. When danger is charged against this indulgence, let us remember that, while only one of our three presidential assassinations can be in any way related to a public opportunity for the people to greet the president, such opportunity has in many millions of honest hearts rekindled wholesome Americanism, and made more deep and warm patriotic impulse. Against one miscreant who, with a desperate foolhardiness that can hardly be again anticipated, has through access to the head of our nation accomplished a murderous purpose, we should not forget the countless numbers of those who in the privilege of like access would prevent such accomplishment with their lives. All things considered, it is a serious question, even at a time when all are aroused to the need of better protection of the president, whether a serious limitation of the people’s public access to him is justified as either necessary or effective.

It is not amiss to add that in discussing the curtailment of the privileges long accorded to the public in this regard, the president himself must be reckoned with. We shall never have a president who is not fond of the great mass of his countrymen and who is not willing to trust them. His close contact with them is inspiring and encouraging. Their friendly greeting and hearty grasp of his hand, with no favors to ask and no selfish cause to urge, bring pleasant relief from official perplexities and annoying importunities. The people have enjoyed a generous access to their president for more than a hundred years. Weighing the remote chance of harm against the benefit and gratification of such access both to himself and the people, it can hardly be predicted that a project for its abolition would be sanctioned by any incumbents of the presidential office.

It is by no means intended to suggest that this access should be unregulated and entirely free from all precaution. Those charged with care for the president on such occasions should never in the least degree tolerate the idea that there can be a harmless person of unsound mind; nor should they relax their watch for such persons and for all others that may properly be suspected of a liability to do harm. Every doubtful case should be determined on the side of safety, and all suspicious movements or conduct should challenge prompt and effective caution. Such precautions can be taken quietly and unostentatiously. It may be safely said, however, that among the millions interested in having such precautions for presidential safety adopted, the president himself will be the least anxious concerning them. This will always be so.

A serious and thorough consideration of the peril which has so shockingly broken in upon the peace of our national life would be incomplete in its lesson and warning if it failed to lead to an honest self-examination and a frank inquiry whether there are not causes other than anarchistic teachings, and perhaps near our own doors, whose tendency, to say the least, is in the wrong direction. Have not some of our public journals, under the guise of wholesome criticism of official conduct, descended to such mendacious and scandalous personal abuse as might well suggest hatred of those holding public place? Has not the ridicule of the coarse and indecent cartoon indicated to those of low instincts that no respect is due to official station? Have not lying accusations on the stump and even in the halls of Congress, charging executive dishonesty, given a hint to those of warped judgment and weak intellect that the president is an enemy to the well-being of the people?

Many good men who are tearful now, and who sincerely mourn the cruel murder of a kindly, faithful, and honest president, have perhaps from partisan feeling or through heedless disregard of responsibility supported and encouraged such things. They may recall it now and realize the fact that the agents of assassination are incited to their work by suggestion, and this suggestion need not necessarily be confined to the dark councils of anarchy.

Not the least among the safeguards against presidential peril is that which would follow a revival of genuine American love for fairness, decency, and unsensational truth.

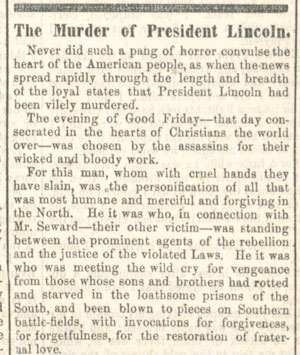

Life After Lincoln

At least one in six Americans can remember the last time a U.S. president was assassinated. And almost all of them can tell you exactly where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. They can probably also recall their feelings of sorrow, anger, and bewilderment when they heard President Kennedy was dead.

John Atherton

February 12, 1944

Those feelings must have been even more intense in Americans 150 years ago when they heard the news of the first presidential assassination. The president’s death would probably have seemed even more tragic as they realized that Lincoln would never see the reconciliation he’d worked so hard to achieve.

He’d spent the last four years holding the Union cause together, prodding generals, and supplying arms and men to defeat the Confederacy. But with victory in sight, he showed no animosity toward the Rebels. And though he had never spelled out his postwar plans for reconstructing the union, it was widely known he favored clemency toward the Southern secessionists.

Many in the North were hungry for vengeance, including Lincoln’s vice president, who advocated hanging many of the Southern “traitors.” Lincoln was one of the lone voices favoring forgiveness and reconciliation with the South. In his second inaugural address, he asked Americans “to bind up the nation’s wounds … to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves.” Just a week before his death, while he was touring recently captured Richmond, a Union general asked Lincoln how he should treat the conquered Confederates. Lincoln said he didn’t want to give specific orders but added, “If I were in your place, I’d let ’em up easy, let ’em up easy.”

Days after the president’s death, Post editors wrote that they had once sided with the president’s “generous and merciful projects and desires.” But that was before he was shot by John Wilkes Booth, “a representative of those whom [Lincoln] was striving with all his might and influence to shield and benefit.”

The editors still admired Lincoln, but admitted he had a fault of leaning “too much towards gentleness and mercy.” Perhaps Lincoln was wrong, and God had intervened to correct the mistaken notion of mercy:

Has this cruel deed been allowed in the orderings of an all-wise Providence, that we may fully understand the hearts of these men with whom we have been contending, and waste no foolish magnanimity on those who seem incapable of responding to it? Such are the questions which at this moment every loyal man in the North is putting to himself.

To such questions, the editors had their answer: “We feel as if all other feelings were swept aside by the single demand for justice.” As for Lincoln’s call to forgive the South: “The voice of Mercy in our heart has been stilled forever” by the same bullet that silenced the voice of Lincoln.

History shows that vengeance grew stronger in the wake of Lincoln’s death, further complicating the reconciliation he had hoped to achieve.